Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology

By Stephen E. PalmerNovember 27, 2022 ⋅ 131 min read ⋅ Textbooks

There is no red or green. All the colors we see are artificial; they're constructs of the mind. This beautiful rainbow of colors you see here on these felt-pens is, in reality, different shades of gray.

Part I: Foundations

Chapter 1: An Introduction to Vision Science

- Most of us take for granted our ability to see the world around us.

- Yet when viewed critically, visual perception is so incredibly complex that it almost seems like a miracle.

- How do we quickly and effortlessly perceive a meaningful 3D scene from the 2D pattern of light that enters our eyes?

- This is the fundamental question of vision.

- Three domains of vision

- Phenomena of visual perception

- E.g. Colors, shape, size, distance.

- Nature of optical information

- E.g. Wavelength, intensity, distance.

- Physiology of the visual nervous system

- E.g. Retina, visual cortex, neurons.

- Phenomena of visual perception

- Understanding all three domains and their relationships is required to explain vision.

Section 1.1: Visual Perception

- This chapter covers: the nature of visual perception from an evolutionary perspective, the nature of optical information from surface light reflected into the eyes, and lastly the physiology of the nervous system that underlies our ability to see.

- Although the eyes are important to see, large parts of the brain are just as crucial.

- What we learn here forms the scaffolding for information in later chapters.

- Visual perception: the process of acquiring knowledge about environmental objects and events by extracting information from the light they emit or reflect.

- Notes on this definition

- The acquisition of knowledge is what separates an eye from a camera. Cameras don’t know anything about the scenes they record and don’t act on visual information.

- Perception isn’t just about an observer’s visual experiences but also the objects and events in the environment.

- Optical information is the foundation of all vision and comes from the way physical surfaces interact with light.

- The difference between emitting and reflecting light is that emitted light only comes from a source, while reflected light uses light from an emitted source.

- What is visual perception for?

- Vision evolved to aid in the survival and successful reproduction of organisms. And not just seeing, but hearing, touching, tasting, and smelling all participate in this goal.

- Not all species rely as heavily on vision as we do, but vision is important to us because it provides spatially accurate information from a distance.

- E.g. Bats don’t rely heavily on vision but instead use echolocation to gather information.

- Sound and smell can provide information from an even greater distance, but they’re rarely as accurate as vision is for identifying and location objects.

- Taste and touch provide the most direct information about objects but they can’t provide information from far distances.

- For evolution, visual perception is only useful if it’s reasonably accurate otherwise it would have never evolved to such an accurate level in humans.

- Light is an enormously rich source of environmental information and human vision exploits it to a high degree.

- Veridical perception: perception that’s consistent with the actual state of the environment.

- But is vision a clear window into reality?

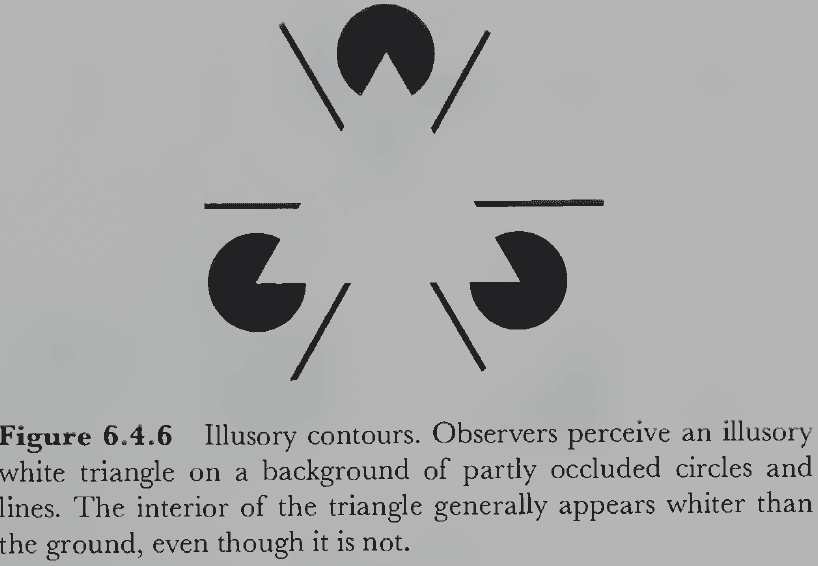

- No, and exceptions include adaptation, afterimages, visual illusions, ambiguous figures, and hallucinations.

- Adaptation

- Visual experience becomes less intense with prolonged exposure to a stimulus.

- E.g. If you go outside at night, you first only see a few dim stars but after a few minutes, you start to see more stars and brighter stars. The stars don’t emit more light as you continue gazing, but your visual system becomes more sensitive to the light they do emit.

- What changes over time is our visual system and not the environment.

- Afterimage

- Strong visual stimuli sometimes leave an impression after the stimuli has disappeared.

- E.g. A blinding camera flash is followed by a dark spot afterimage where the flash retinally was.

- This is clearly not veridical perception because the afterimage lingers long after the physical flash is gone.

- Illusions

- Stimuli that fool our visual system into making perceptual errors.

- Visual illusions support the fact that perception is fallible and can’t be considered a clear window into reality.

- The reality that vision provides (perception) must be a construction by the visual system from the way it processes light information.

- The nature of this construction implies certain hidden assumptions, assumptions that we aren’t conscious of and when untrue result in illusions.

- It’s easy to get carried away by illusions and claim that vision is grossly inaccurate and unreliable, but this is a mistake.

- Vision is only as accurate as it needs to be for evolutionary purposes.

- Later we’ll consider the possibility that the perceptual errors produced by illusions may actually be harmless side effects of the same processes that produce veridical perception under normal circumstances.

- The point is that illusions prove that perception isn’t just a simple registration of objective reality.

- Vision must be an interpretive process that somehow transforms complex, moving, 2D patterns of light at the backs of our eyes into stable perceptions of 3D objects in 3D space.

- We conclude that the objects we perceive are actually interpretations based on the structure of images rather than direct registrations of physical reality.

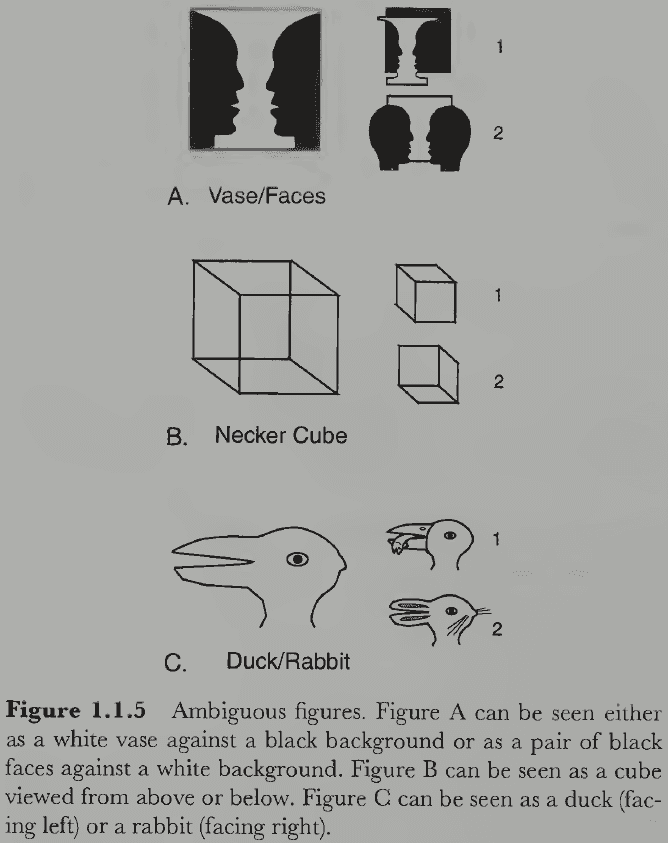

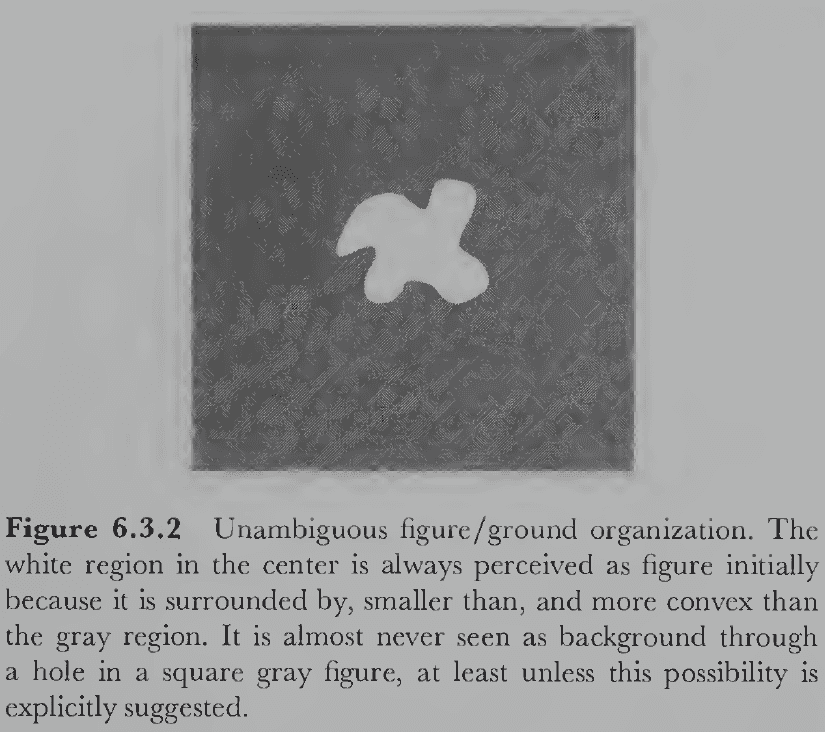

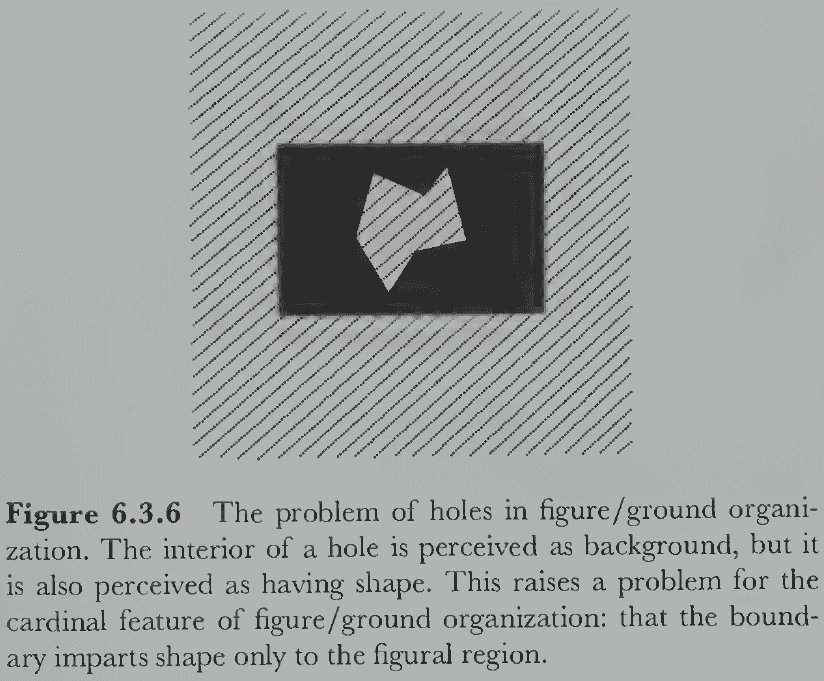

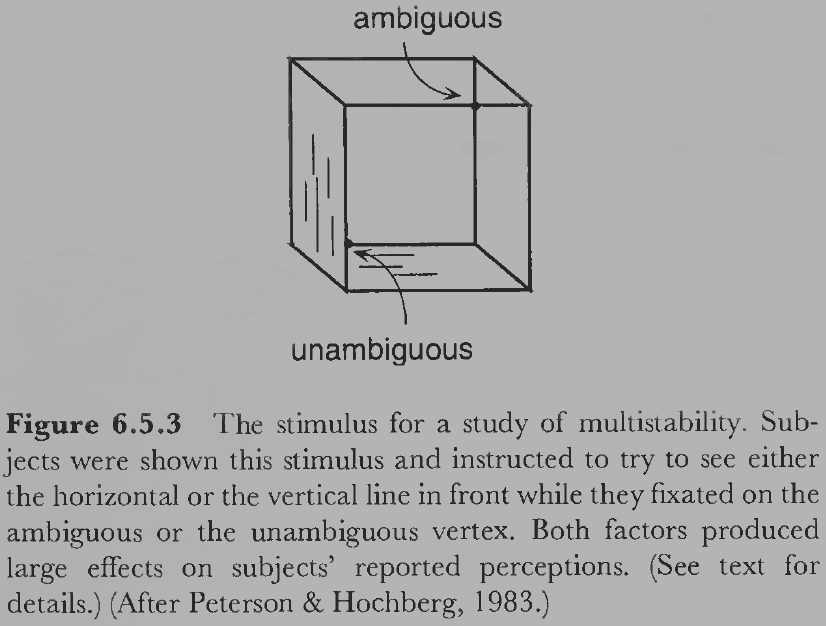

- Two facts about ambiguous figures

- The two interpretations are mutually exclusive and can’t occur simultaneously; only one model fits the sensory data at any one time.

- Both interpretations form a multistable perception where both possibilities switch back and forth as you continue looking at them. It seems that both interpretations compete where the winner is perceived until it gets “tired”.

- If perception were a true reflection of reality, then no ambiguous figures could exist.

- This suggests that something more complex and creative is occurring in vision beyond the information just in light.

- Our current hypothesis is that the brain constructs a model of what environmental situation might have produced the observed pattern of sensory stimulation.

- Perception matches the constructed model rather than the actual sensory stimulation, and sometimes these models are wrong or that multiple models are equally plausible.

- This isn’t to say though that the models are made-up or are fiction.

- Perceptual models must be closely coupled to the sensory information of the world and provide reasonably accurate interpretations of this information to be evolutionary useful.

- Illusions show us that our models are sometimes inaccurate and ambiguous figures show us that our models are sometimes identical, but these are under rare and artificial circumstances.

- Our everyday experience tells us that our perceptual models are usually both accurate and unique.

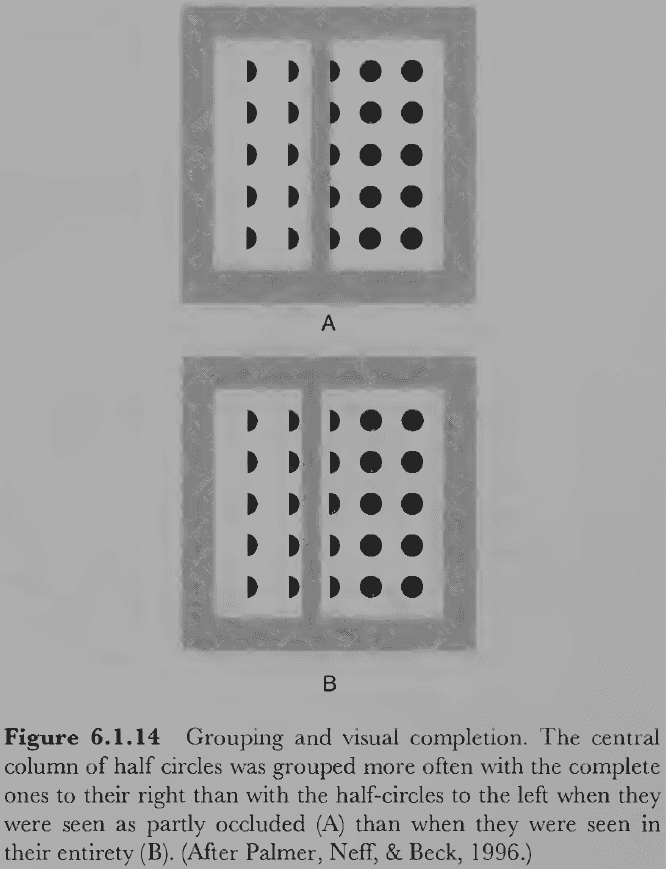

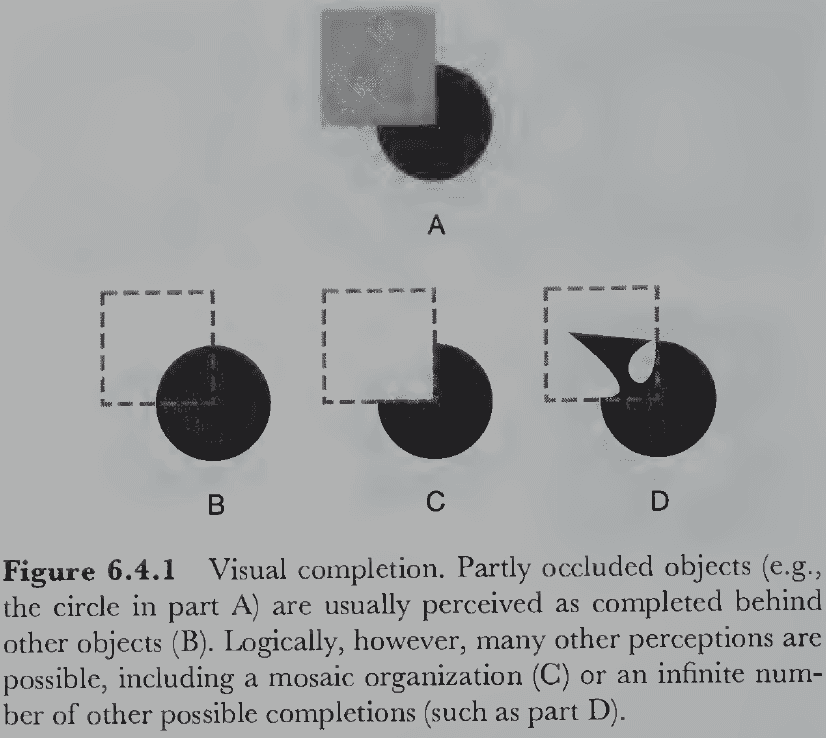

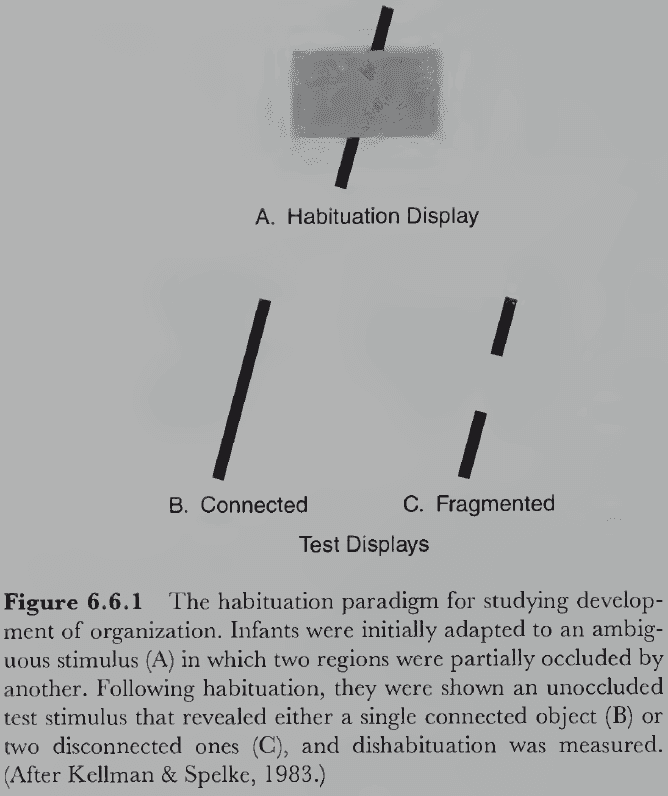

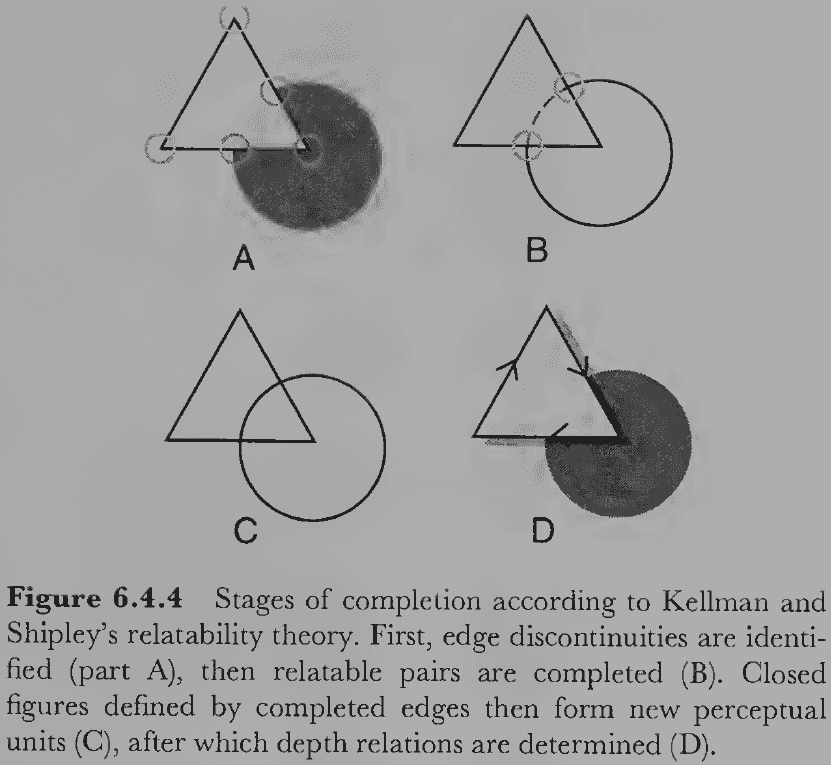

- Another piece of evidence for the model-constructive view of visual perception is that we complete surfaces we can’t see.

- E.g. If one object partially blocks another object, we understand that the blocked object is still complete and whole.

- Almost nothing we see is visible in its entirety, yet almost everything is perceived as whole and complete.

- Self-occluded surfaces: surfaces of an object that are entirely hidden from view by its own visible surfaces.

- E.g. You can’t see the back of a person if you’re seeing their face.

- Impossible objects: 2D line drawings that seem like 3D objects but are physically impossible.

- The existence of impossible objects further show how our perceptions are internal constructions of a hypothesized external reality.

- Why did perception evolve to form models?

- At some level, the answer must be that the models were more useful than the raw images for evolution.

- E.g. Models help to predict the future and are invariant to viewpoint changes such as movement and lighting.

- Models take more time and effort to construct but once built are easier to maintain and use.

- E.g. It’s useful to know the current position of a moving object, but it’s more useful to know its current direction and speed to predict its trajectory.

- An important note is that the process of extrapolation must work faster than the predicted event to be useful, which may be why perceptual predictions are generated so quickly.

- Classifying objects is useful because it allows us to respond in appropriate ways given the vast amount of information we have stored from previous experiences with similar objects.

- Classification makes handling new objects easier because objects in the same class share many properties and behaviors.

- E.g. Things that are alive move and behave differently than things that are dead.

- However, classifying objects is difficult and an unsolved problem.

- There are also cognitive constraints, top-down goals, plans, and expectations that influence perception.

- This makes sense because the purpose of perception is to meet the needs of the organism using the opportunities afforded by the environment.

- When an object has your attention, you become conscious of its detailed properties.

- But attending to an object doesn’t have to mean moving your eyes to fixate on it, even though it usually means that.

- E.g. Staring at something but thinking about something else or not looking at something but thinking about it.

- Many high-level aspects of perception seem to be fully conscious whereas most lower levels don’t seem to be accessible, modifiable, or conscious.

Section 1.2: Optical Information

- Visual perception depends on three ingredients: light, surfaces that reflect light, and the visual system of an observer that can detect light.

- Without any of these ingredients, visual perception doesn’t occur.

- We study each of these ingredients for their basic facts. This section covers how light interacts with surfaces.

- Light that enters our eyes must somehow carry information about the environment, information that we can use for survival and reproduction.

- Optics: the branch of physics that studies light.

- Luminance: the number of photons falling on a given surface per unit of time.

- The luminance of light covaries to some degree with its perceived brightness, but the relation is far from simple.

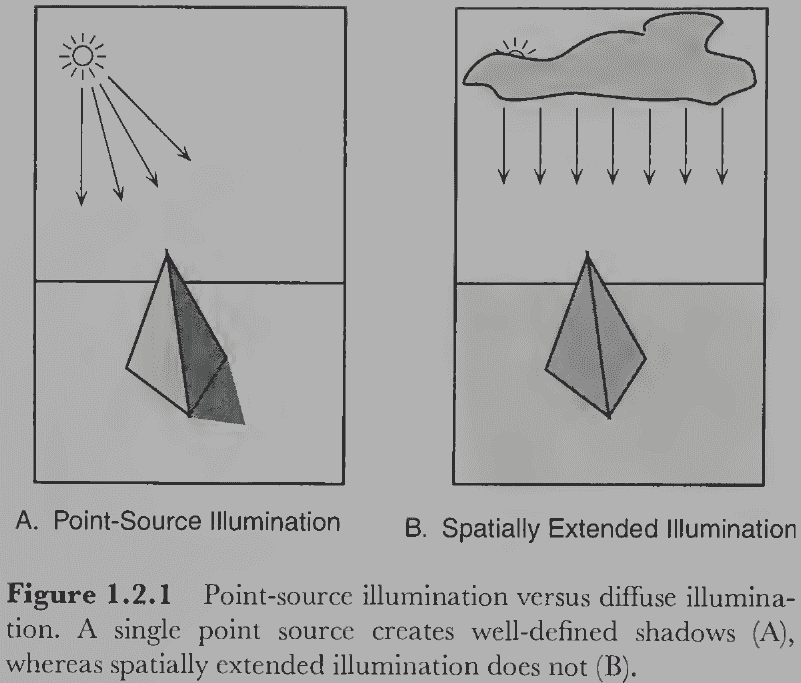

- Illumination: the lighting conditions in the environment.

- E.g. A point-source illuminant like the Sun or a diffuse-source illuminant like the Sun over some clouds.

- Having more light sources complicates the optical structure of the environment.

- Three ways light can interact with surfaces

- Transmission

- Absorption

- Reflection

- These photon-surface interactions are what ultimately provide vision with information about surfaces, except for transparent surfaces.

- Of the three types of interactions, reflection is the most important for vision because reflected light is changed by its interaction with the surface and it can be captured by the eye.

- Review of specular (mirror-like) and matte surfaces. Real surfaces fall somewhere between the two.

- Some light bounces in almost every direction off almost every surface in the environment, so every surface acts as a secondary light source.

- We can go further and introduce third-order and higher-order reflections.

- The richness of natural scenes depends on capturing these higher-order reflections, these complex interactions of ambient light with the structure of the physical environment.

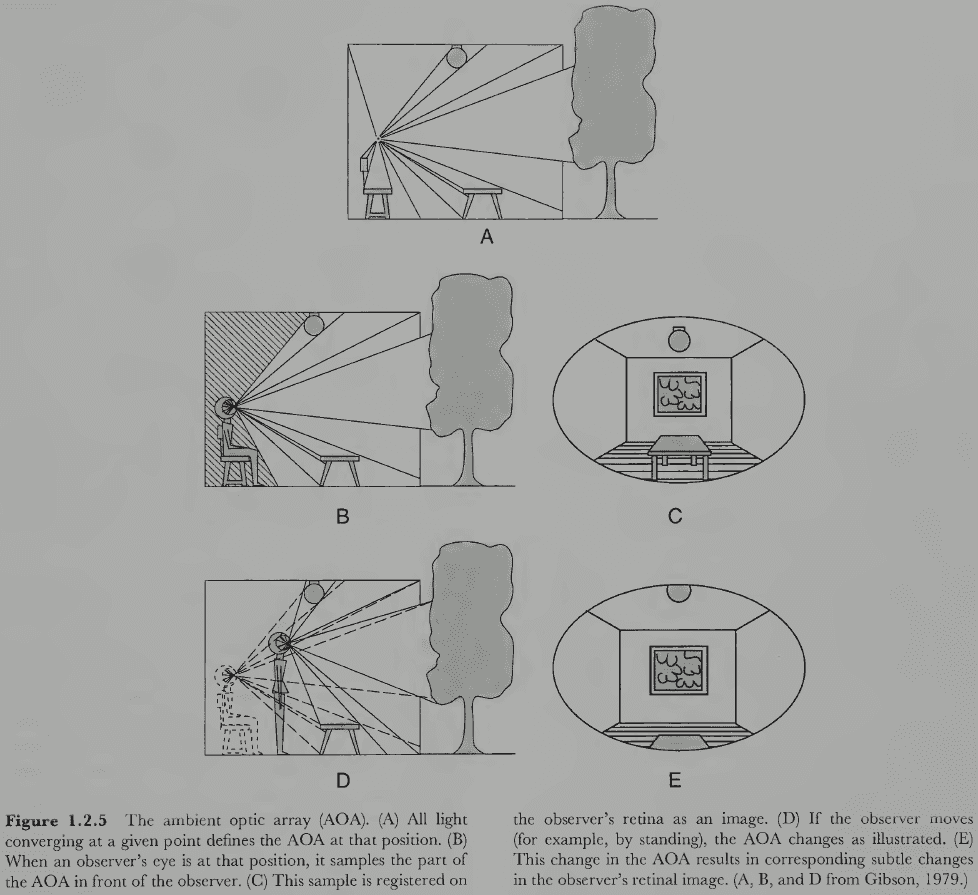

- Ambient optical array (AOA): all the light coming towards a given point of observation.

- The light in the AOA is complex but follows laws that provide information vision can exploit.

- Vision is the process of reverse inference, of determining the arrangement of surfaces that must exist in the environment to have structured the AOA in just that way.

- The eyes only sample a directional (front-facing) subset of the AOA and there is a different AOA at every point in the environment.

- If we move, we extend the static AOA into a dynamic AOA.

- The static AOA is characterized by a pattern of light converging at the observation point, while the dynamic AOA is characterized by the optic flow of light over time.

- The dynamic AOA is important because it provides more information and allows us to perceive depth, the shapes of moving objects, and our own trajectory as we move.

- If vision provides accurate information about the external world, then there must be a consistent relationship (laws) between the geometry of environmental surfaces and the light that enters the eye at a specific observation point. And there are such laws.

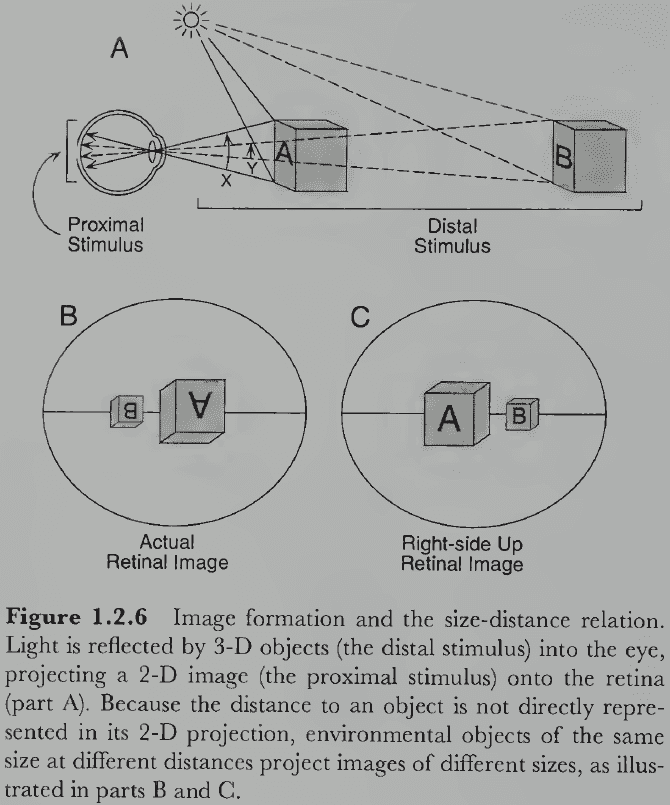

- Distal stimulus: the object in the external world.

- Proximal stimulus: the object’s optical image at the back of the eye.

- Visual angle: the number of degrees occupied by the proximal stimulus.

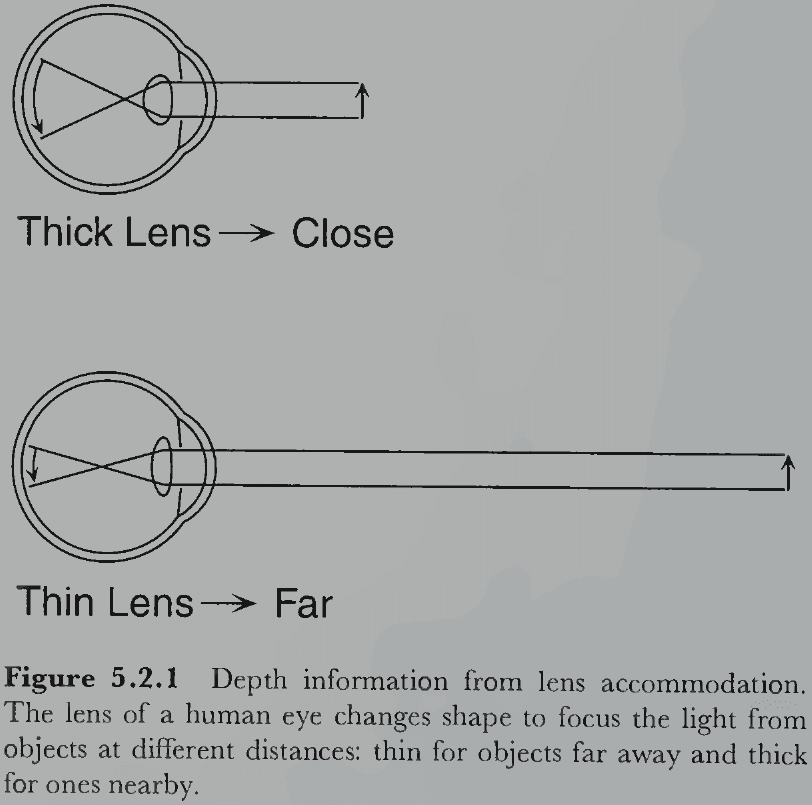

- It’s important to know that the image on the retina has only two spatial dimensions rather than three, so vital spatial information has been lost going from the real 3D world to the eye’s 2D image of it.

- E.g. Depth information is lost from the projection of the 3D world onto a 2D surface.

- To perceive the world in three dimensions, we must somehow recover depth information from the 2D image. This may be possible, however, because the projection from a 3D to 2D image is highly lawful and consistent.

- Projective geometry: the mathematical study of how a higher-dimensional space is mapped onto a lower-dimensional space.

- E.g. In dynamic vision, the projection is from the 4D structure of space-time onto the 3D space of optic flow that unfolds over time on the 2D surface at the retina.

- No notes on pinhole camera, perspective projection, convex lens.

- One issue with using a pinhole camera is that too large of an aperture makes the image blurry. This can be solved by using a convex lens that provides a virtual pinhole at its focal point, which is what our eyes do.

- No notes on perspective versus orthographic projection. Orthographic projection can be thought of as a special case of perspective projection when the distance is infinite between object and focal point.

- The early stages of visual perception try to solve the inverse problem.

- Inverse problem: how to go from optical images of a scene to knowledge of the objects that gave rise to them.

- There’s no easy way to solve the inverse problem because going from the 2D image to the 3D environment has many possible solutions.

- Each point in the image could map into an infinite number of points in the environment.

- Sensory data doesn’t provide enough information to obtain a specific solution, so it’s surprising how our brains manage to come up with the correct solution most of the time.

- We know 3D perception is possible because the human visual system can do it.

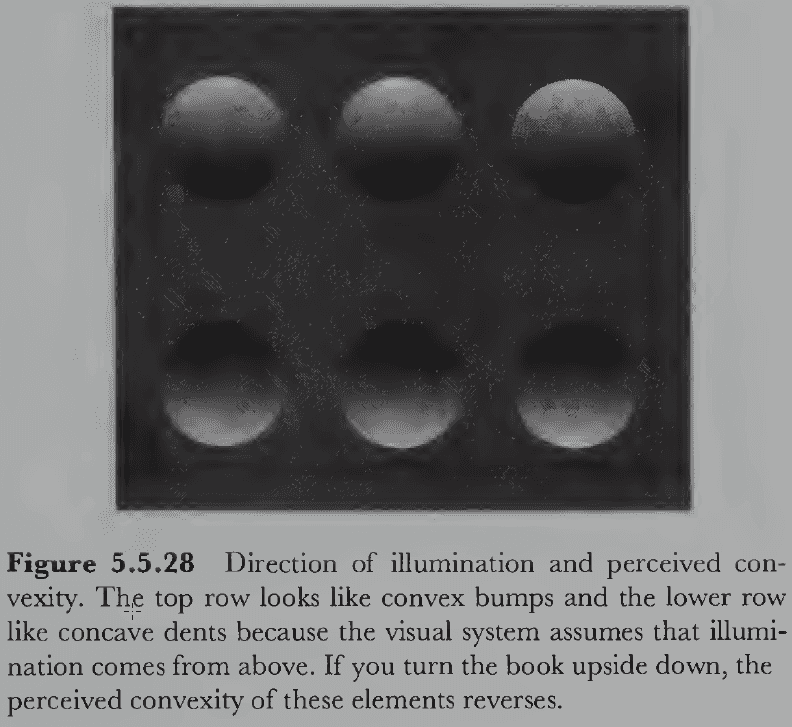

- The dominant theory explaining our 3D perception ability argues that the ability is possible because the visual system makes a lot of highly plausible assumptions about the nature and conditions of the environment.

- These assumptions constrain the inverse problem enough to make it solvable most of the time.

- Thus, vision is a heuristic process.

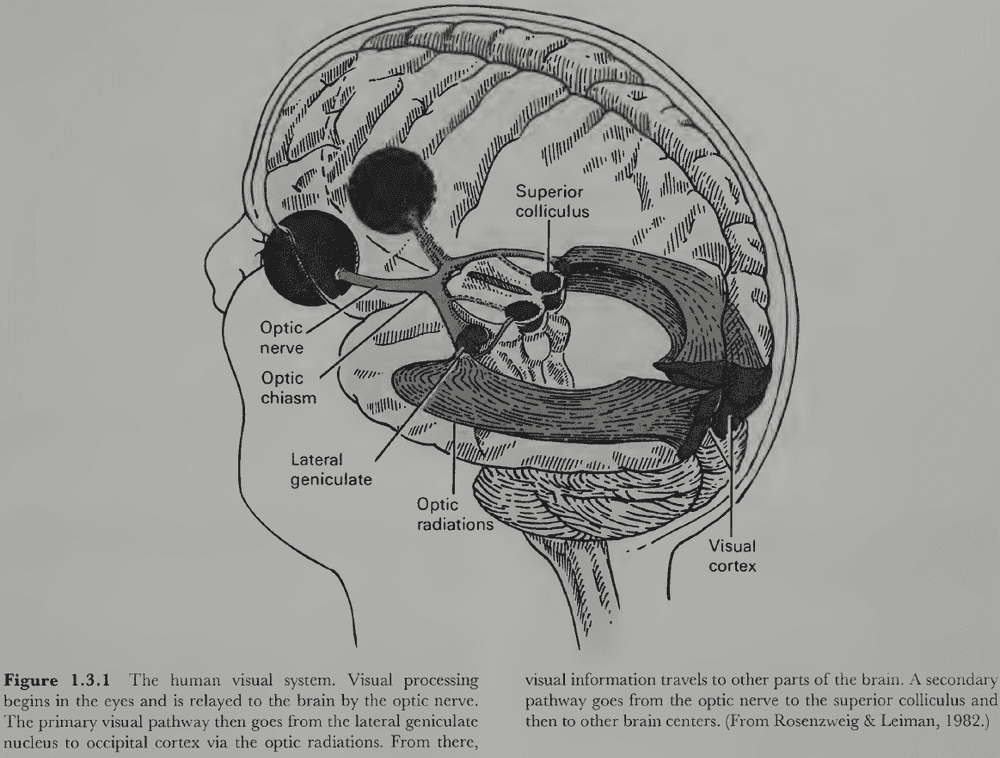

Section 1.3: Visual Systems

- Once we’ve mastered some of the basic facts about the hardware of the visual system, it’s anatomy or physical structure, we can then turn to what it does, its physiological or biological function.

- Vision occurs when light from external sources is reflected from surfaces of objects and enters the eye.

- The visual system consists of both eyes and the brain areas that process information from the eyes.

- The fact that both eye and brain are required for vision means that a person with normal eyes but damaged visual brain might be as blind as a person with a normal brain but damaged eyes.

- Blindsight: blindness due to damage to parts of the visual cortex.

- E.g. Blind spots in the visual field, describing faces but unable to identify them, or seeing stationary scenes but can’t perceive motion.

- We shouldn’t take for granted the simple facts about our eyes.

- E.g. Some species can’t move their eyes but must instead move their entire head. Some species have their eyes placed on the sides rather than the front.

- Eye placement reflects the tradeoff between accuracy of depth perception and coverage of the visual world.

- E.g. Eyes placed in the front have excellent depth perception but poor coverage, while eyes placed on the sides have poor depth perception but excellent coverage.

- No notes on eye anatomy such as cornea, aqueous humor, pupil, and iris.

- Interestingly, pupil size also changes in response to psychological factors.

- E.g. Positive emotional reactions and mental effort.

- We have no conscious control over the mechanisms that control pupil size.

- After the optics of the eye have done their job, the next important function of the eye is to convert light into neural activity.

- Review of neuron, dendrite, graded potential, cell body, action potential, axon, neurotransmitter, synapse, photoreceptor, rod, cone, horizontal, bipolar, amacrine, ganglion cells, and fovea.

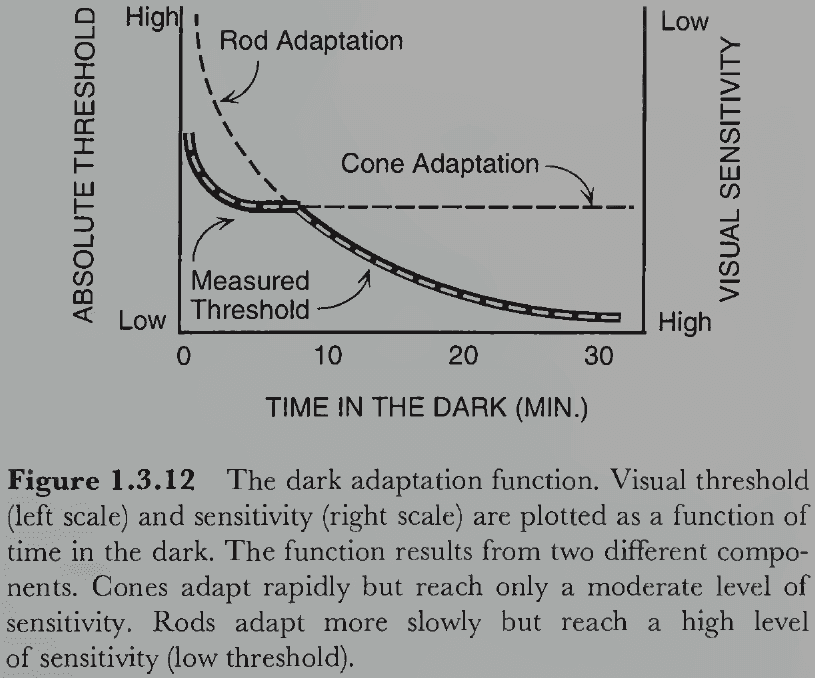

- Our ability to adapt to dark environments doesn’t smoothly increase over time as cones and rods have different adaption curves.

- Peculiarities of retinal design

- The photoreceptive layer is the last layer of the retina but it would make more sense for it to be the first layer since it’s the one capturing light.

- Rods and cones appear to be pointing backwards with their light-sensitive segment the furthest from the incoming light. This might be because the enzymes for pigment regeneration are opaque and can’t be in front of the photoreceptors.

- Blood vessels block incoming light but our brain adapts to and ignores them.

- The optic disk or blind spot is where all of the ganglion cell axons leave the eye and it has no photoreceptors. We don’t experience blindness here except under special circumstances.

- The photoreceptors of vertebrates actually respond to light by decreasing synaptic activity. Invertebrate eyes work in the opposite and more intuitive way by increasing their output for increases in light intensity.

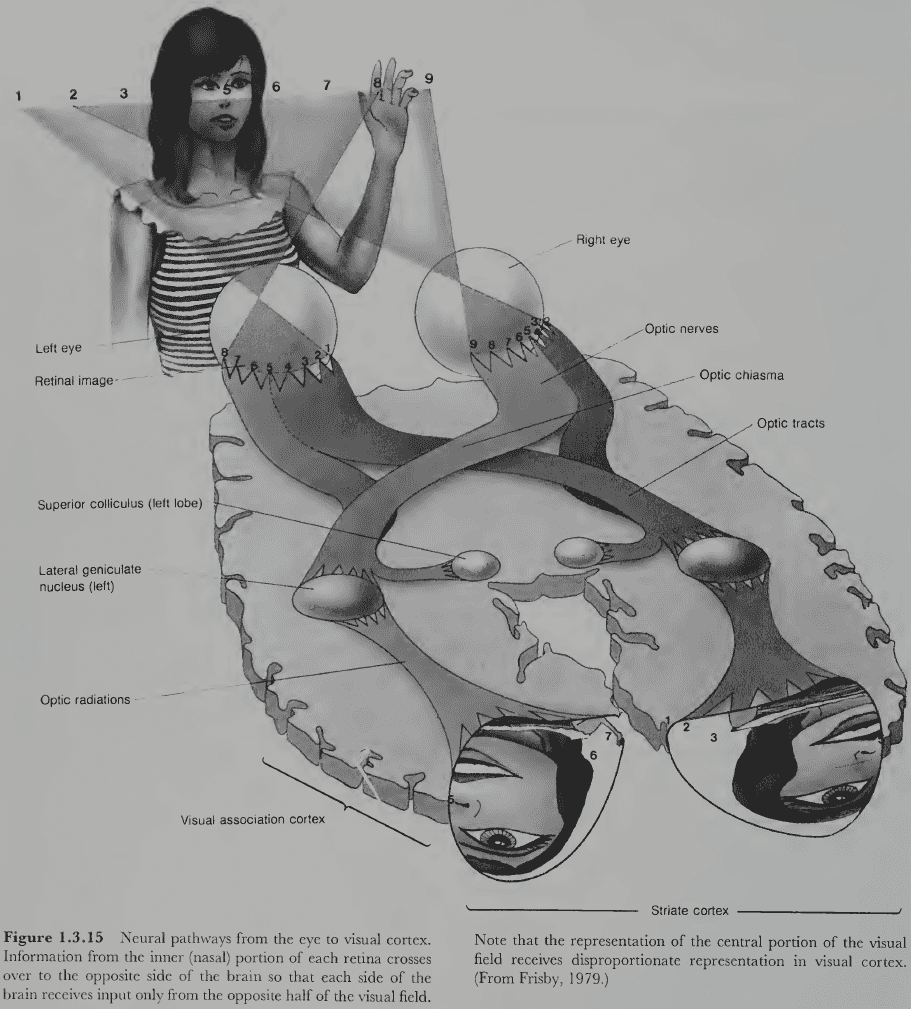

- Review of the optic chiasm (where the fibers from the nasal side cross), superior colliculus, lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN), occipital cortex, and localization.

- We still don’t know the extent to which functions are localized, but the evidence increasingly supports the view that it is.

- The mapping from retina to striate cortex is topographical.

- E.g. Nearby regions on the retina project to nearby regions in the striate cortex.

- Cortical magnification factor: how the fovea receives a much greater representation in the cortex than the periphery.

- This factor means that we have more detailed spatial information about objects in the central region of the retina, and not that the perception of space is distorted so that objects in the center appear bigger.

- A brain area is marked as “visual” if it follows the topographic organization of the retina.

- The visual cortex is a patchwork quilt of small maps that code for different aspects of retinal stimulation.

- E.g. Brightness, color, motion, depth, texture, and form.

- Review of the ventral “what” visual pathway and dorsal “where” visual pathway.

- Visual agnosia: deficits in identifying objects by sight.

- E.g. Some patients can’t recognize a person from their looks, but can recognize them by their voice. This isn’t due to the inability to see as such patients can describe the faces they see quite precisely.

- Unilateral neglect: the inability to attend to objects in the opposite half of the visual field of the brain damaged site.

- Much of the visual cortex is hidden within the folds of the cortex.

- Review of the primary visual cortex (V1) and the six layers of the cortex.

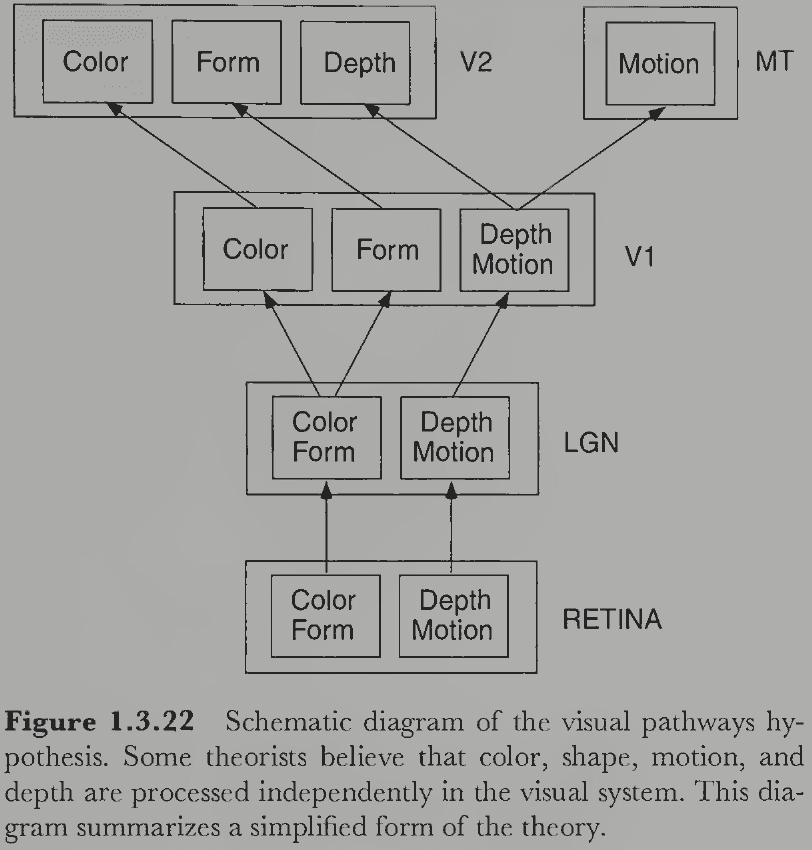

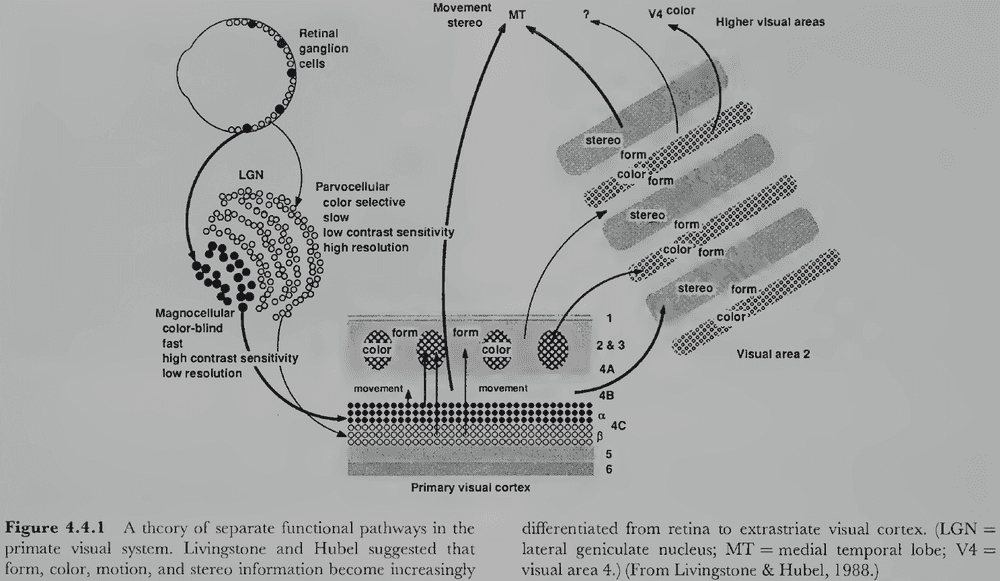

- Physiological pathways hypothesis: that there are separate neural pathways for processing information about different visual properties.

- E.g. Color, shape, depth, and motion.

- The nature of visual processing in higher level areas of cortex is less clear than in area V1.

Chapter 2: Theoretical Approaches to Vision

- Theory: an integrated set of statements/hypotheses about the underlying mechanisms or principles that organizes and explains known, unknown, and predicted facts.

- We’ll examine many theories but one common feature among all of them is that they all ultimately prove to be inadequate.

- However, we can learn from wrong theories by trying to improve them and they may contain pieces of the truth.

- The answers to all possible experimental questions wouldn’t lead to proper scientific understanding because that’s just a list of facts.

- Proper understanding requires a theory that integrates old facts and predicts new facts.

- A theory relates facts to each other and allows them to be derived from a small and consistent set of underlying assumptions.

Section 2.1: Classical Theories of Vision

- Why do things look the way they do?

- Four issues of visual perception

- Environment versus organism.

- Things look the way they do because that’s what they are and that’s how our visual nervous system evolved.

- Empiricism versus nativism.

- Empiricism argues that things look the way they do because we’ve learned to see them that way.

- Nativism argues that things look the way they do because we were born to see them that way.

- Atomism versus holism.

- Atomism argues that things look the way they do because each small piece of the visual field appears that way versus the whole visual field.

- Holism argues that how one part of the field appears will be strongly affected by how other parts of the field appear.

- Introspection versus behavior.

- Should a perceptual theory be derived from phenomenological observations of one’s own conscious experience or from objective measurements of human performance?

- Environment versus organism.

- Different theories take different stances on these four issues.

- Structuralism

- Perception comes from when basic sensory atoms evoke memories of other sensory atoms.

- Sensory atom: a primitive, indivisible element of experience in a given sense modality.

- Rapid and unconscious associative memory processes were thought to underlie perception.

- Trained introspection was used to discover sensory atoms.

- Gestaltism

- Rejected nearly everything about structuralism and argued that perceptions had their own intrinsic structure as wholes that couldn’t be reduced down to parts.

- The simple concatenation of parts rarely captured the perceived structure of the whole.

- How does the structure of the whole emerge from its subparts?

- Psychophysiological isomorphism: perceptual experiences are structured the same as their underlying brain events.

- E.g. For the opponent theory of color, the opponent color pairs (red/green, blue/yellow, and black/white) should match the opponent structure in the neural events underlying color perception.

- Ecological optics

- Proposed that perception could be better understood by analyzing the structure of the organism’s environment; it’s ecology.

- This theory is about the informational basis of perception in the environment rather than its mechanistic basis in the brain.

- How does the world structure light in an ambient optic array (AOA) such that people perceive the environment by sampling information?

- E.g. Texture gradient provides information about surface tilt, light source direction, etc.

- Perceiving as the active exploration of the environment.

- However, the additional information from the temporal dimension doesn’t fully solve the inverse problem of vision because it doesn’t present a unique solution.

- Constructivism

- Combines many of the three approaches described above.

- Global percepts are constructed from local information.

- Unconscious inference: that the inverse problem can be solved by using assumptions with retinal images to reach perceptual conclusions about the environment.

- Vision is a probabilistic process where it computes the interpretation with the highest probability given the retinal stimulation.

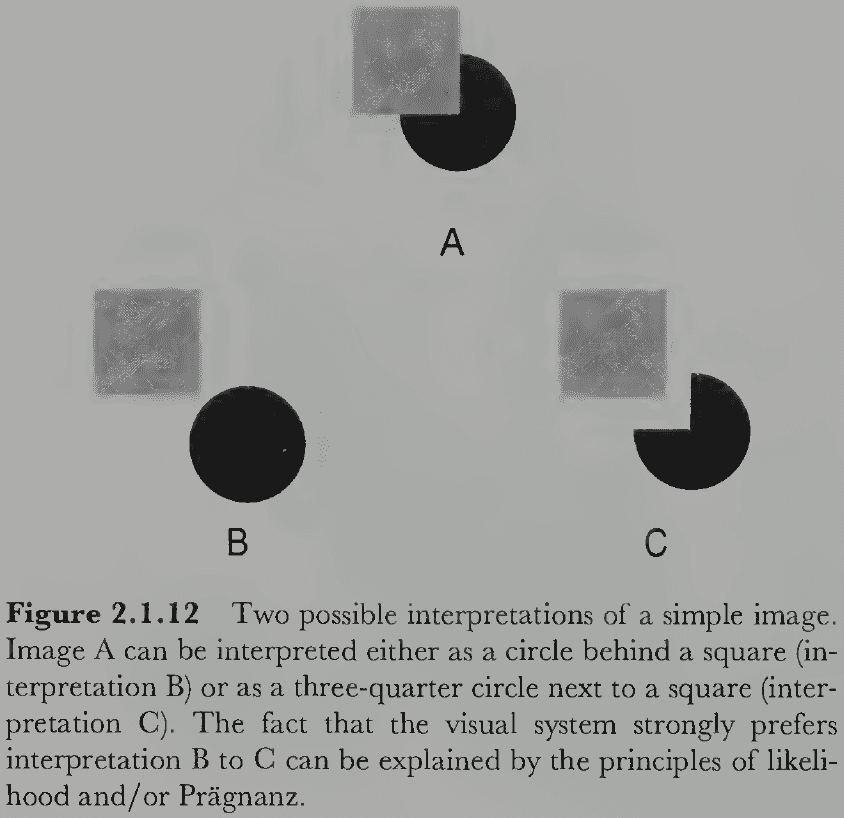

- E.g. A circle behind a square has a higher probability of occurring than a three-quarter circle matching exactly the edges of the square.

- Heuristic interpretation process: the visual system makes inferences about the most likely environmental conditions that could have produced the image.

- It’s a heuristic because it uses probabilistic rules that are usually, but not always, true. If the assumptions are false, they lead to wrong conclusions in the form of visual illusions.

- Perception matches reality when the assumptions are true and become illusory when they are false.

- The more likely the assumptions are true, the more likely the perception is correct.

- The evolutionary utility of vision is maximized by using the most probable assumptions, assumptions that we cover in the rest of the book.

- How exactly does the visual system go beyond the observed information to solve the inverse problem in plausible and effective ways?

- E.g. The visual system assumes that large-scale edges of indoor environments, such as floors, walls, and ceilings, are either aligned with gravitational vertical or are perpendicular to it.

- Illusory perceptions usually occur under highly artificial circumstances because these assumptions tend to be true under normal viewing conditions. However, they also reveal the existence of the assumptions.

- There’s a close interdependence between reality, illusion, and hidden assumptions.

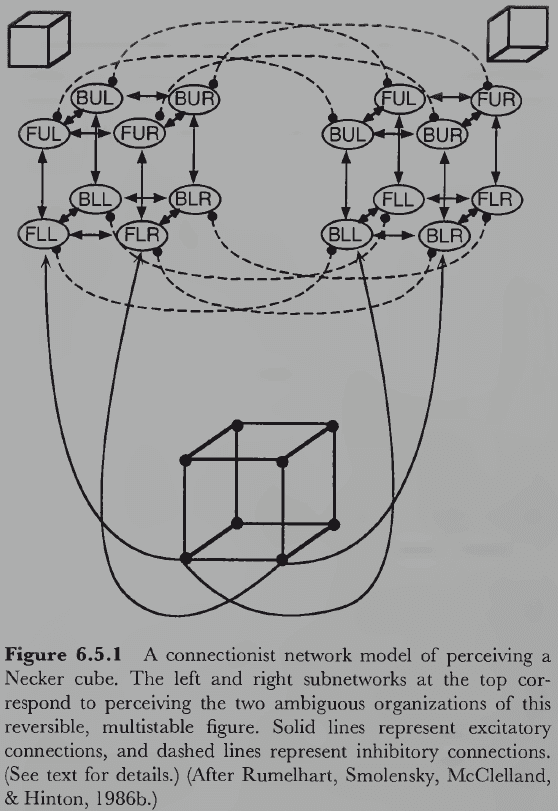

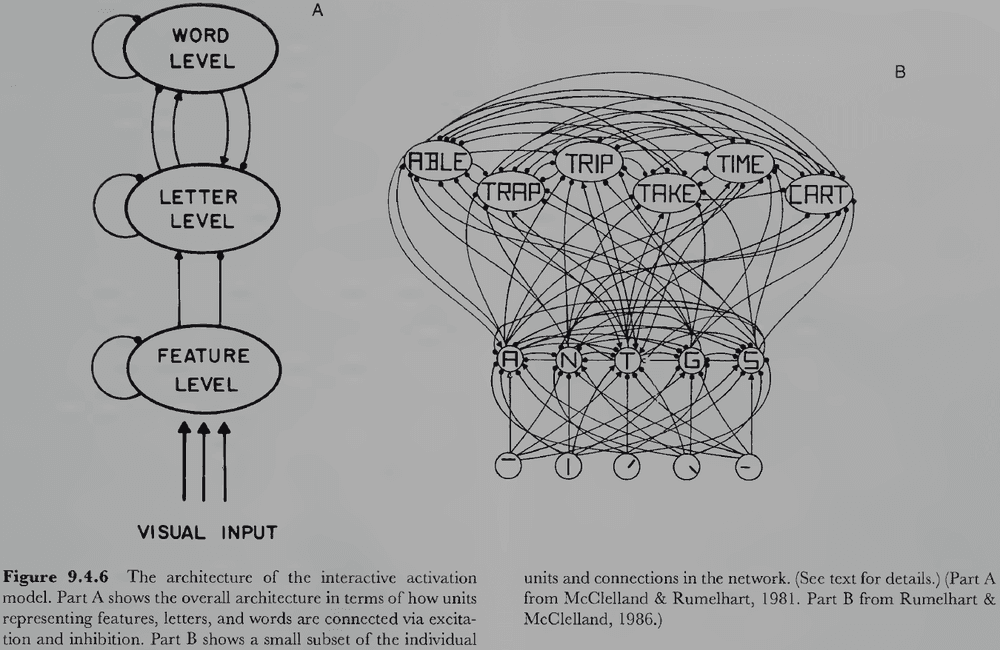

- In terms of implementation, connectionist networks can reach perceptual conclusions based partly on incoming sensory data and partly on additional assumptions embodied by the pattern of interconnections among its neuronlike elements.

Section 2.2: A Brief History of Information Processing

- Three important developments in the 1950s to 1960s

- Use of computer simulations to model cognitive processes

- Application of information processing ideas to psychology

- Emergence of the idea that the brain is a biological processor of information

- No notes on computer vision, the invention of computers, Turing machines, block worlds, neural networks, perceptrons, Hebb’s cell assemblies, and parallel distributed processing (PDP).

- It turns out to be unbelievably hard to get computers to “see” even simple things.

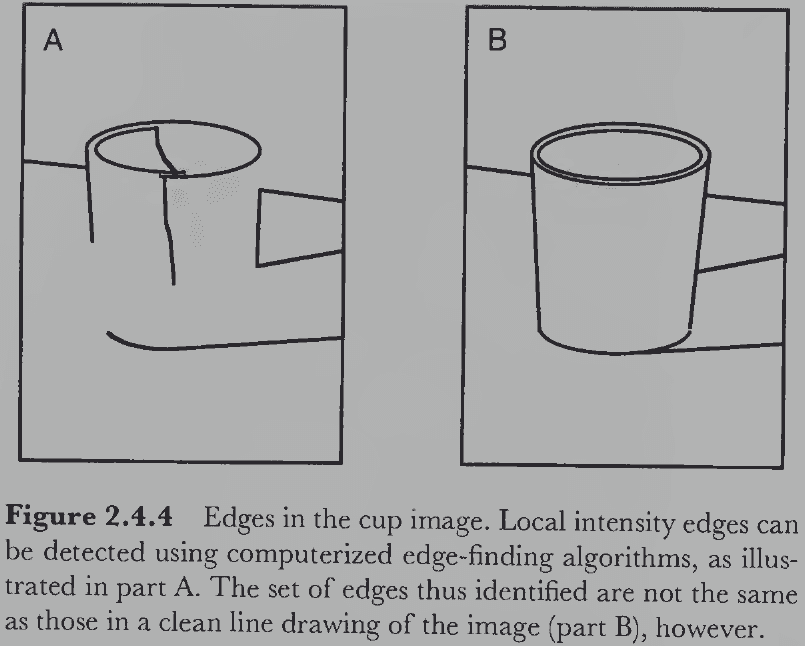

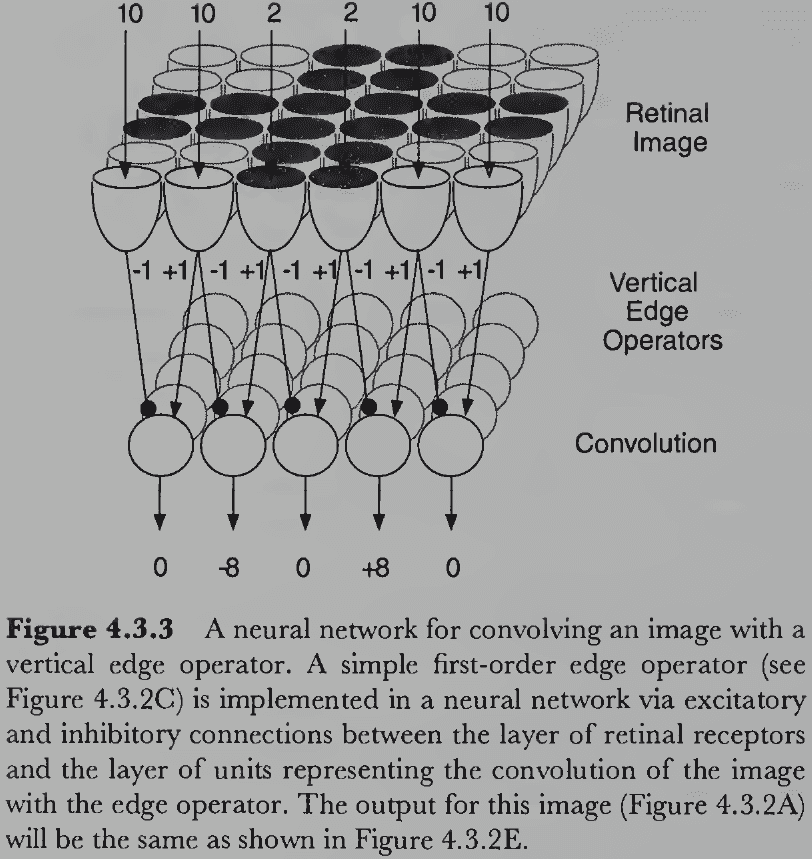

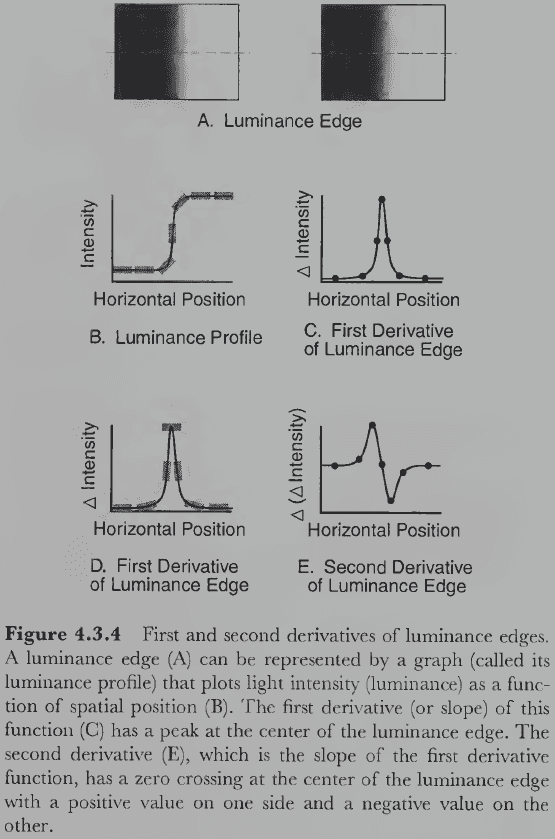

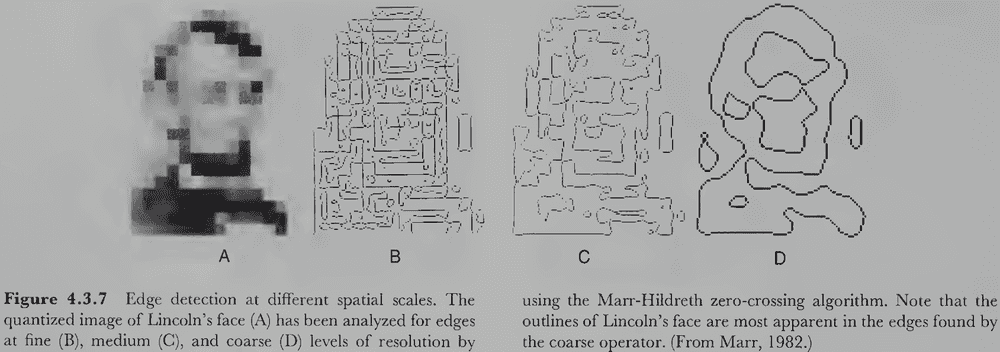

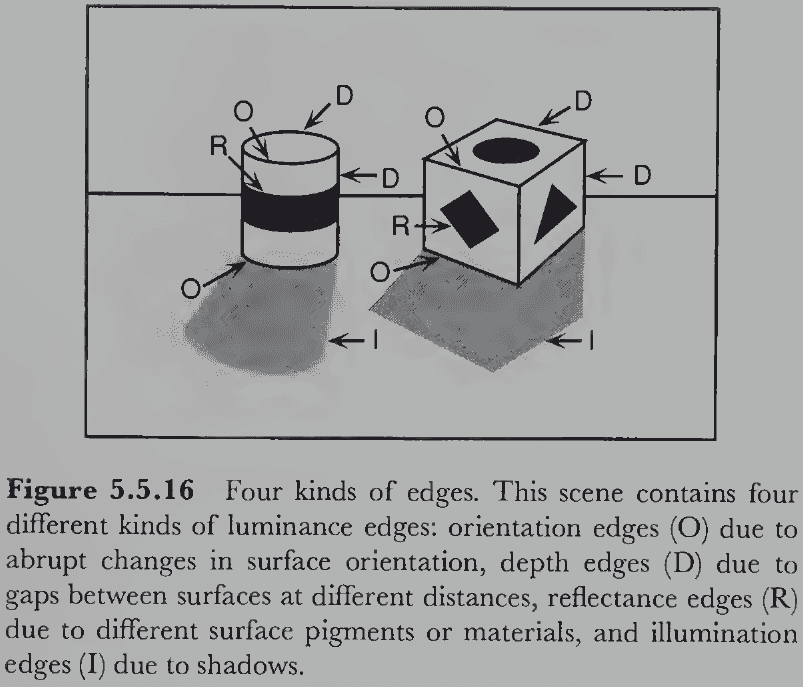

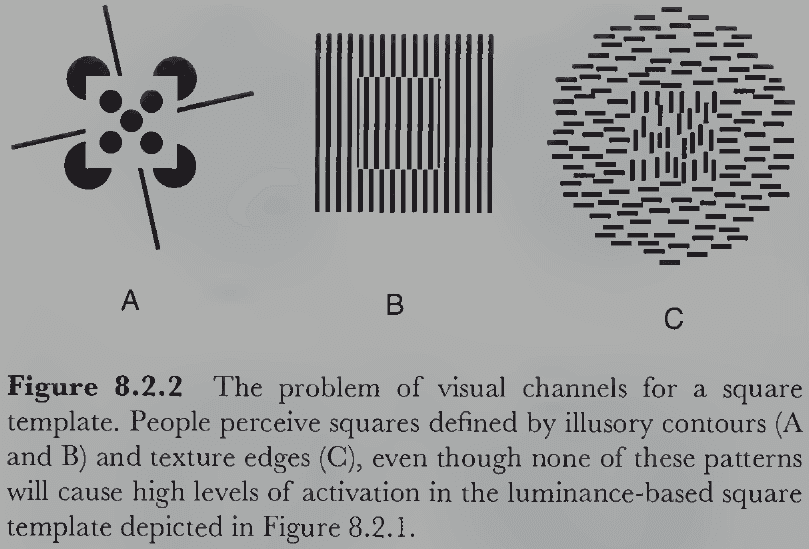

- Luminance edges: changes in the amount of light falling on two adjacent regions of an image.

- The luminance structure in 2D images provides information about the structure of surfaces and objects in 3D space.

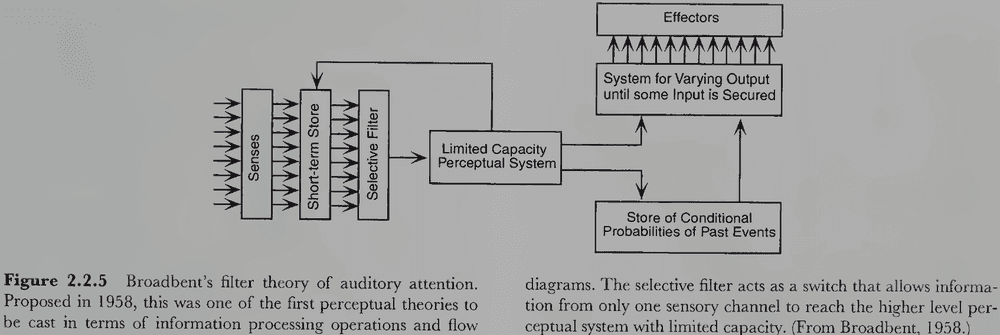

- No notes on behaviorism, Broadbent’s filter theory of auditory attention, iconic memory.

- Broadbent was among the first to propose a psychological theory specifying the temporal structure of information processing events.

- Few neuroscientists take the simple analogy of neural spikes as digital code seriously anymore because there are many striking differences between brains and digital computers.

- But the idea that the brain is doing some kind of information processing is now almost universally believed.

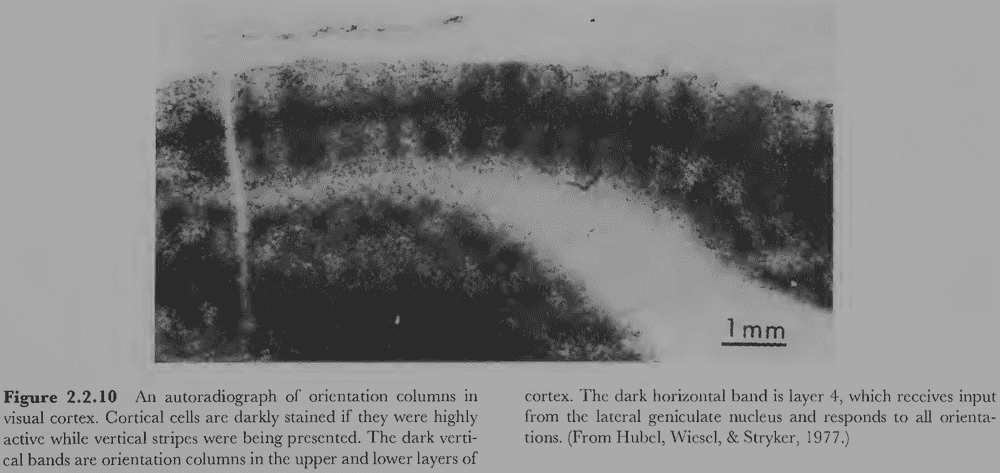

- No notes on lesion experiments, electrical brain stimulation, single-cell recording, Hubel and Wiesel’s work on receptive fields, autoradiography (using a radioactive substance to track the firing of neurons), brain imaging techniques (CT, PET, MRI, and fMRI).

Section 2.3: Information Processing Theory

- The information processing paradigm is a way of thinking about the human mind as a computational process.

- No notes on Thomas Kuhn’s scientific paradigm and the brain-as-a-computer metaphor.

- E.g. Minds as “software” and brains as “hardware”.

- Review of David Marr’s three levels of description: computational (the system’s goals), algorithmic (how a computation is executed), and implementational (algorithm embodied as a physical process).

- Three assumptions of information processing

- Informational description

- Mental events can be described as informational events consisting of three parts: input information, operation, and output information.

- Information events are diagrammed as a black box in an information flow diagram.

- Recursive decomposition

- Any complex informational event at one level can be specified at a lower level by decomposing it into component informational events and a flow diagram.

- E.g. A black box can be defined by a number of smaller black boxes inside it, plus a description of how they’re interconnected.

- This process can be recursively performed again and again for each black box.

- Recursive decomposition only works if the system is actually structured as a hierarchy.

- Physical embodiment

- Information and operations are entities in the abstract domain, while representations and processes are entities in the physical world.

- Informational description

- Representation: a physical entity that carries information about something.

- Process: a physical transformation that changes one representation into the next.

- A representational system includes two similar but distinct worlds: the represented world (external) and the representing world (internal).

- How does an internal world represent an external world?

- One method is by having the internal representation mirror the structure of the external world. Thus there’s a map from external objects to internal representations.

- A standard tradeoff in representing information is that the more information is stored directly, the less must be inferred by additional processing and vice versa.

- Without representations, processes would have nothing to work on. And without processes, no work would get done.

- Processes make implicit information in the input representation explicit. However, processes can’t create information from thin air.

- All the information must be available either in the optical structure projected to the retina or from internal knowledge of the viewer.

- E.g. The boundaries between retinal regions projected from different surfaces and how surfaces are combined to form objects.

- Visual perception thus combines external and internal information to make meaningful facts about the environment available to the organism; it’s a form of inference.

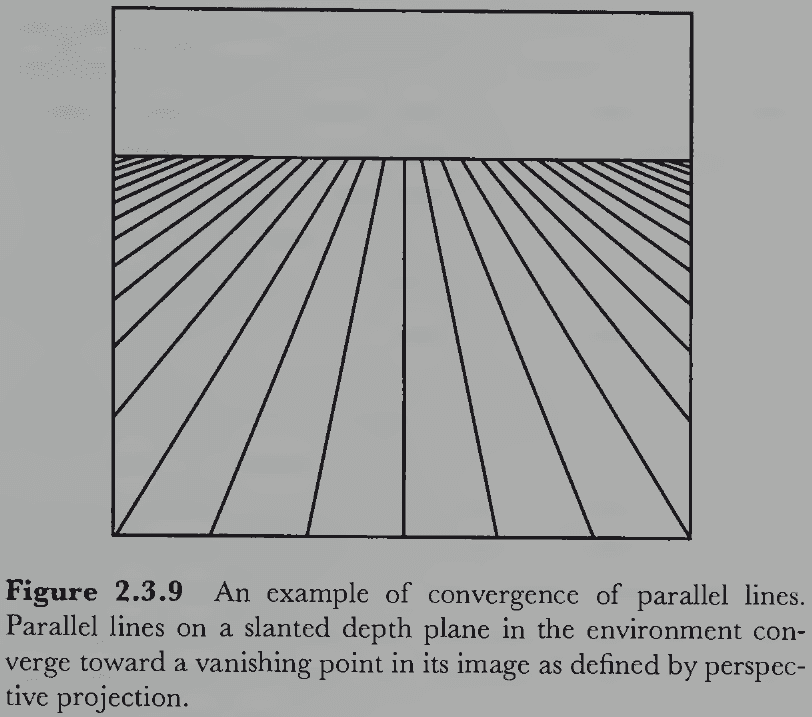

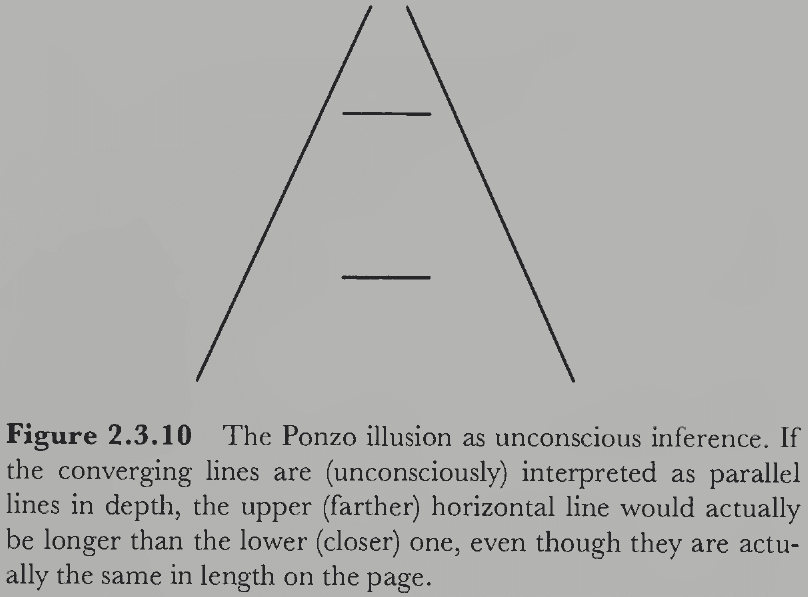

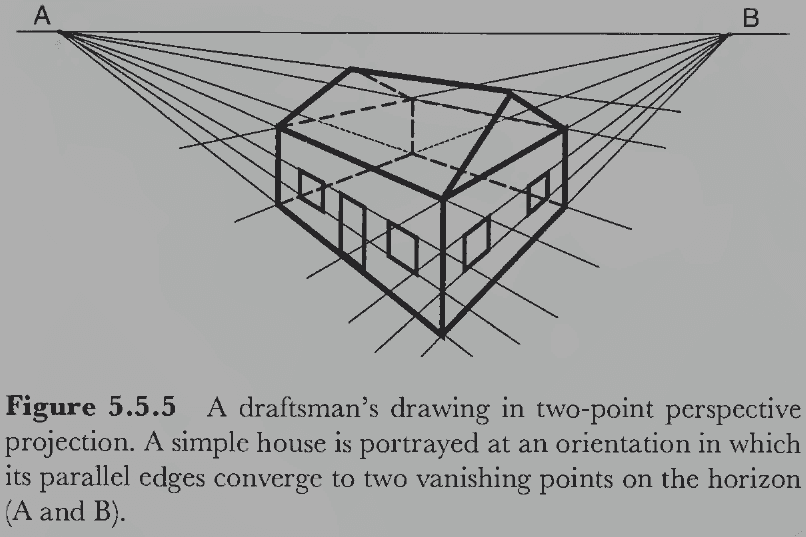

- E.g. An image with a set of lines converging towards a vanishing point, plus the convergence assumption (lines converging to a point on the horizon are parallel), lets the visual system conclude that the converging lines are actually parallel lines.

- No notes on deductive and inductive inference.

- Most inferences in visual processing are inductive because they’re not guaranteed to be true.

- E.g. The assumption that converging lines are parallel isn’t always true, but only probabilistically true. It’s false for the converging but nonparallel sides of a trapezoid.

- If the assumption is false for the current situation, then the conclusion may not be valid.

- This is how inferential theories of vision account for the existence and nature of many visual illusions.

- E.g. The Ponzo illusion may be due to the unconscious misapplication of the convergence assumption.

- An important function of perceptual learning is to collect the most appropriate hidden assumptions so that veridical perception is achieved as often as possible.

- However, in the case of conflicting assumptions, how does the visual system determine which inference is correct?

- E.g. The lines in Figure 2.3.9 can be perceived to lie at the same distance (same plane) or be perceived as receding into the distance. The former assumption supports the conclusion that the converging lines aren’t parallel in depth, while the latter assumption supports that the lines are parallel.

- If different assumptions lead to different conclusions, one can’t conclude anything using both assumptions.

- So, one assumption must be selected to the exclusion of other assumptions. This isn’t ideal though as we now need a competitive framework.

- Alternatives to competition

- Soft constraints: informational restrictions that may be overridden.

- Fuzzy logic: statements can have different degrees of truth.

- Probabilistic inference: uses Bayes’ theorem to select the assumption.

- One argument against the inferential perspective of vision is that visual illusions occur in very odd and artificial conditions that would rarely, if ever, show up naturally.

- Yet, the phenomena do occur and require an explanation; we can’t just ignore evidence.

- This book takes the stance that a perceptual theory must account for all phenomena of visual perception, whether natural or not.

- Inference-based vision is preferable to direct perception because it can explain both natural and unnatural phenomena.

- We’ll also adopt the stance that perception involves some form of inductive inference carried out by computations in neural networks.

- Review of top-down (hypothesis-driven) and bottom-up (data-driven) processes where the retinal image is at the bottom and subsequent interpretations are farther along the visual pathway.

- Our intuition suggests that vision is a bottom-up process and while that may be true for the early processing stages, this can’t be true for all of visual perception.

- E.g. Perception of the present state produces expectations about the future. These are top-down components because higher-level interpretation aren’t observed.

Section 2.4: Four Stages of Visual Perception

- Four stages

- Image-based

- Surface-based

- Object-based

- Category-based

- The complete set of firing rates in all receptors of both eyes and their organization is the first representation of optical information within the visual system.

- The representation is complicated by the uneven distribution of receptors and the four different kinds of receptors.

- We can simplify this by assuming the retina captures light in a x-y grid pattern.

- E.g. Pixels or picture elements.

- Pixel: the primitive indivisible unit of visual information that represents an intensity value at the location.

- The coordinate system of the retinal image is presumed to be tied to the structure of the retina.

- E.g. Center of coordinate system is the fovea.

- Past the retinal stage is the image-based stage.

- E.g. Local edges and lines, matching images in the left and right eyes.

- The luminance edges detected in an image aren’t the same edges that people typically perceive.

- No notes on Marr’s raw and full primal sketch.

- Common underlying structure of image-based representations

- Image-based primitives

- 2D geometry

- Retinal reference frame

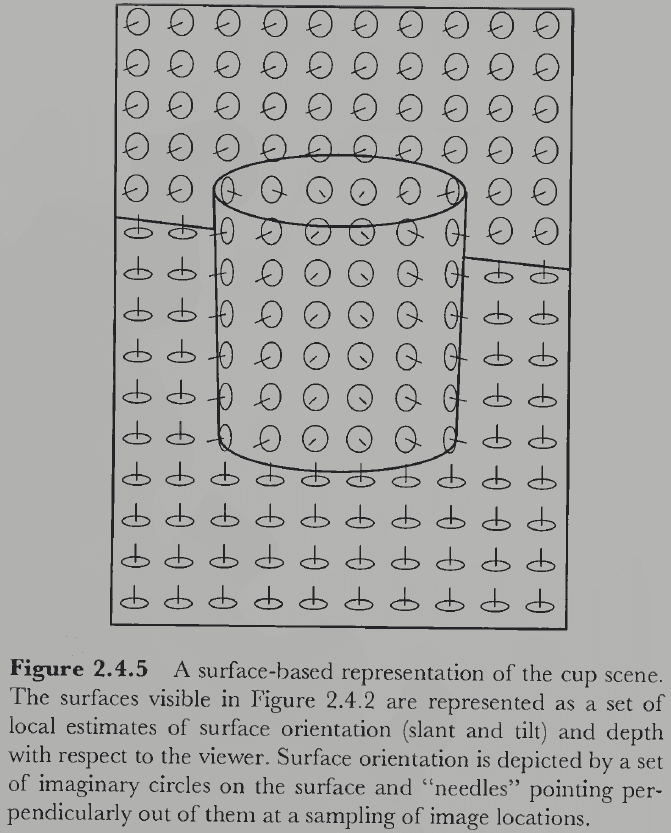

- The second stage is the surface-based stage and it deals with recovering the properties of visible surfaces that might have produced the features discovered in the image-based stage.

- One distinguishing feature of the surface-based stage is that it represents information in three dimensions.

- It doesn’t represent all surfaces, only the visible ones, and can’t be computed from only retinal images because it uses additional assumptions.

- Properties of surface-based representations

- Surface primitives: local patches of 2D surface at some slant located at some distance.

- 3D geometry

- Viewer-centered reference frame: surfaces are represented in a 3D coordinate system based on the viewer.

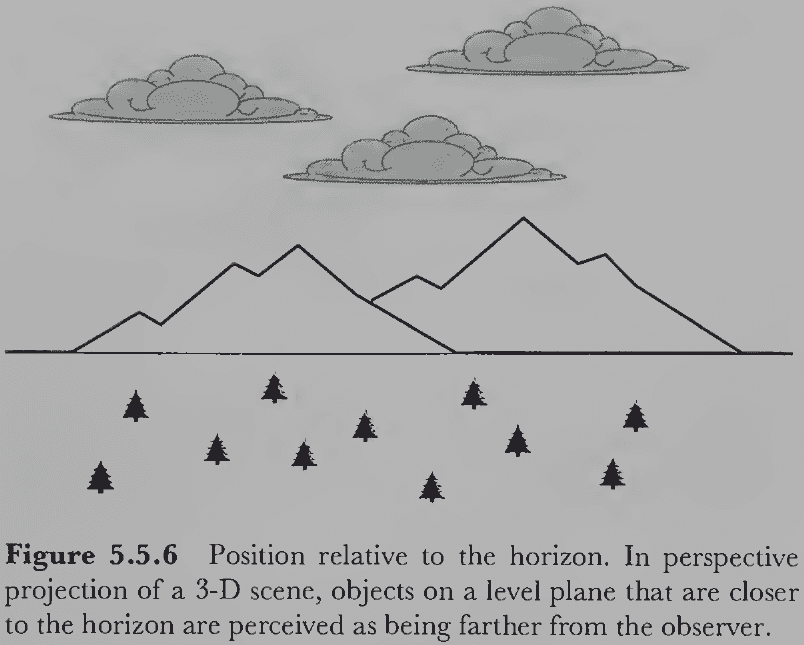

- The representation of surface is constructed from several image-based features.

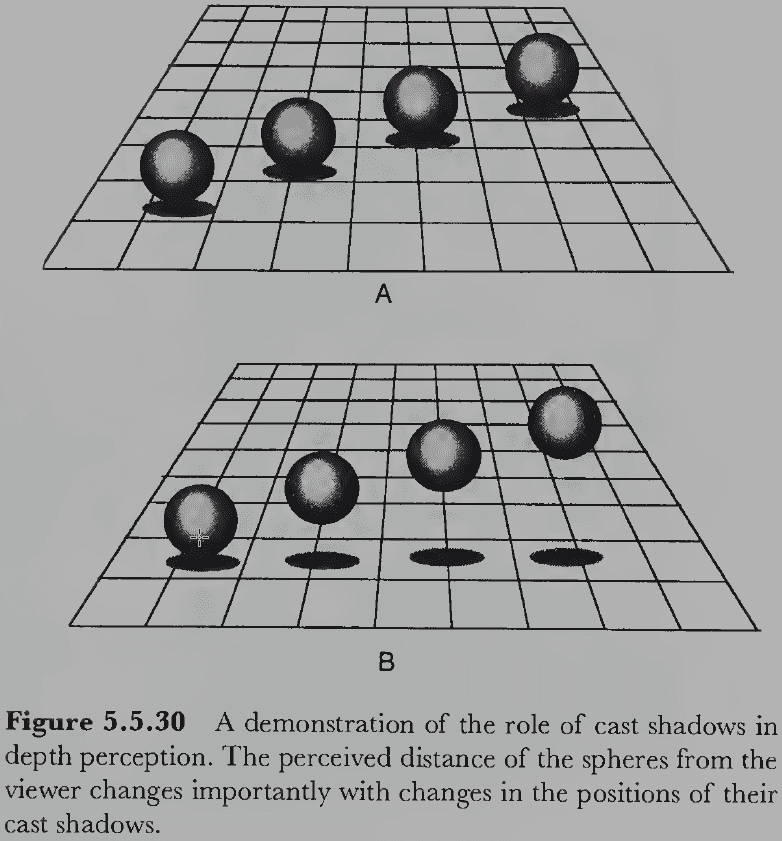

- E.g. Stereopsis, motion parallax, shading and shadows, texture, size, shape, and occlusion.

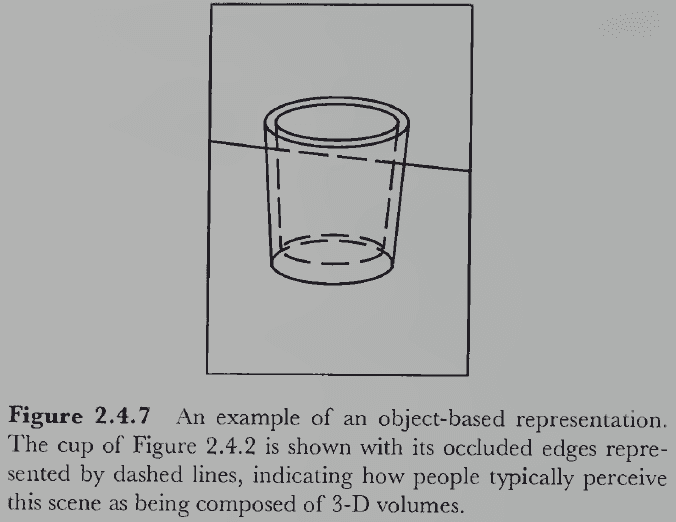

- The fact that we have expectations about partially and completely hidden surfaces suggests that there’s some form of true 3D representation that includes occluded surfaces.

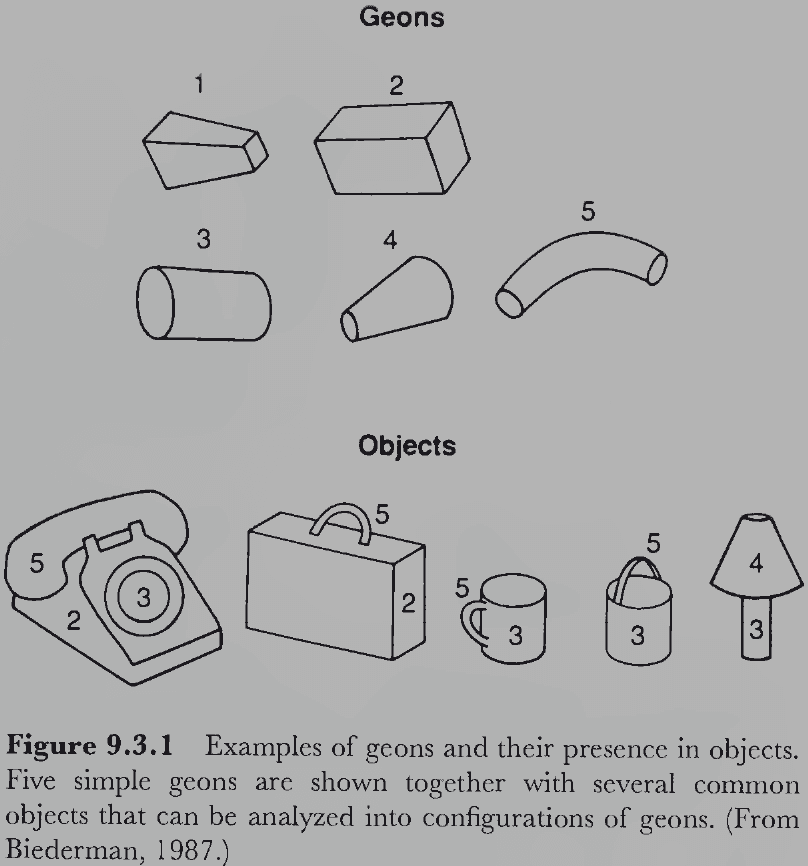

- The object-based stage is when visual representations truly include 3D information.

- However, to achieve this representation, the visual system has to make further hidden assumptions because now the inferences include information about unseen surfaces or parts of surfaces.

- Two ways to construct an object-based representation

- Boundary approach: extend the surface-based representation to include unseen surfaces in a 3D space.

- Volumetric approach: conceive of objects as intrinsically 3D entities and represent them using some set of primitive 3D shapes.

- In object-based representations, are the primitive elements surfaces or volumes? We don’t know.

- The ultimate goal of perception is to provide the organism with accurate information about the environment to aid its survival and reproduction.

- This strongly implies that the final stage of perception deals with recovering the functional properties of objects.

- This final stage for vision is the category-based stage where we believe the functional properties of objects are accessed through categorization (or pattern recognition).

- E.g. Visual system → Classifies object by visual features → Access information about the object class such as function and form → Apply information to object.

- This scheme means that any functional property can be associated with any object.

- An alternative scheme is that the visual system perceives an object’s function directly from its visual characteristics without categorizing them.

- Affordances: whether an object allows a function or behavior.

- It’s possible that we use both types of schemes to perceive function.

- These four stages of visual processing (image-, surface-, object-, and category-based) are our best hypothesis on the overall structure of visual perception.

Chapter 3: Color Vision: A Microcosm of Vision Science

- It’s isn’t obvious why objects should be colored; they simply are.

- People universally believe that objects look colored because they are colored.

- E.g. The sky looks blue because it is blue, grass looks green because it is green.

- But these beliefs are mistaken because neither objects nor light are actually “colored”.

- Color is a psychological property of our visual experiences and not a physical property of objects or lights.

- Color is based on physical properties though and these physical properties are different from the colors we perceive.

- Instead, a more accurate description of color is that it’s the result of complex interactions between physical light and our visual system.

- Color perception may be one of the best understood topics in vision science and how we reached such an understanding may teach us how scientific discovery unfolds over time.

- Steps to understand color

- Consider the nature of the input information: light.

- Consider the nature of the output information: experience of color.

- Then consider the relationship between the two: how the physical domain of light maps onto the psychological domain of color experience.

- We’ll discuss color in terms of image-, category-, and surface-based computational stages. An object-based stage isn’t needed because color is a property of surfaces rather than of volumes.

Section 3.1: The Computational Description of Color Perception

- Review of the physics of color (the discovery that white light consists of colors, review of the photon, electromagnetic energy, wavelength, electromagnetic spectrum).

- The photons we experience as light are just a small part of the electromagnetic spectrum.

- E.g. From 400 to 700 nanometers in wavelength.

- Monochromatic light: light with a spectrum containing only one wavelength.

- Polychromatic light: light with a spectrum containing more than one wavelength.

- E.g. Sunlight is polychromatic because it has a roughly equal number of photons at all visible wavelengths.

- Color only comes into the picture when light enters the eyes of an observer with a visual nervous system to experience it.

- E.g. There’s light of different wavelengths independent of an observer, but there’s no color independent of an observer.

- Different colors appear because different surfaces reflect different proportions of light at different wavelengths.

- All colors can be described using three properties: hue, saturation, and lightness.

- These three properties define the color space: a 3D coordinate system where each possible color experience is represented by a unique coordinate.

- Note that there’s an enormous reduction in complexity from the physical description of light to the psychological description of color.

- E.g. There’s an infinite number of wavelengths between 400-700 nm, but color can be defined with just three values.

- This implies that color experiences lose much of the information carried by the full spectrum of light and that many physically different lights produce identical color experiences.

- Perhaps the lost information was deemed as unimportant by evolution.

- Hue: what we normally think of as color and changes with wavelength.

- If light is arranged by physical similarity in terms of wavelength, then it lies along a straight line where the shortest and longest visible wavelengths are least similar in physical terms.

- But if light is arranged by perceived similarity, then it lies in a circle where the shortest wavelengths (purples) and longest wavelengths (reds) appear close together.

- Thus, the physical dimension of wavelength and the psychological dimension of hue are related, but not identical.

- E.g. The hues between purple and red, like pink, are non-spectral because there’s no single wavelength in the visible spectrum that produces them. These hues can only be created by combining two or more wavelengths of light.

- Complementary colors: hues on opposite side of the color circle.

- E.g. Green and red, blue and orange, yellow and purple.

- Saturation: captures the purity or vividness of color experiences.

- E.g. Grays → Pastels → Vibrant.

- Lightness: refers to the luminance of color.

- For objects that emit light rather than reflect it, we call it’s luminance as brightness.

- Otherwise, the shape of the color space for emitted and reflected light is essentially the same.

- The perception of lightness/brightness is mostly due to the contrast of one region with a surrounding region.

- E.g. If two surfaces reflect the same number of photons per unit time, the surface surrounded by a darker region looks lighter, and the surface surrounded by a lighter region looks darker.

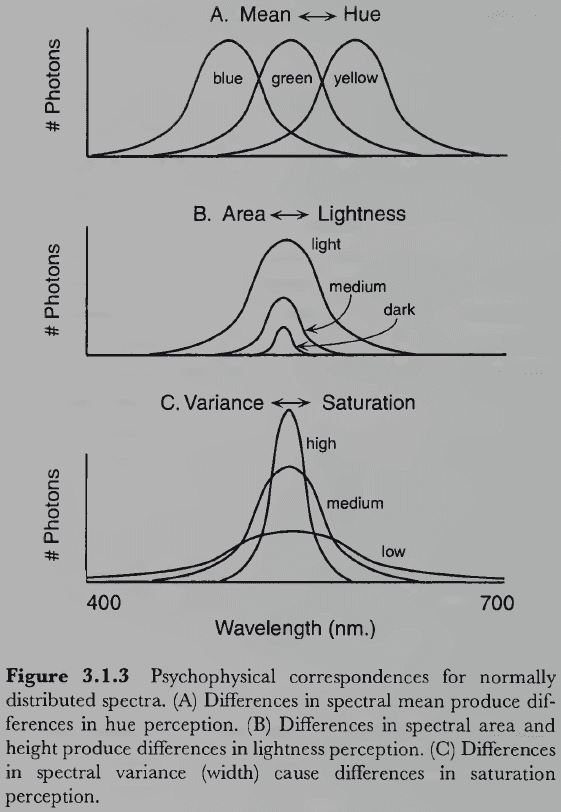

- Psychophysical correspondence: how physical descriptions map onto psychological ones.

- It would be convenient if there were a clear and simple mapping between physical light and color experience, but there isn’t.

- One way to simplify the mapping is to only consider surfaces that reflect light who spectrum is approximately in the shape of a normal distribution.

- Three simple psychophysical correspondences

- Mean wavelength determines hue.

- Not all hues can be produced by normally distributed spectra.

- E.g. Non-spectral purples.

- Spectral area determines lightness.

- The area under the curve matches the total number of photons that hit the retina.

- Variance determines saturation.

- Monochromatic lights (which have zero variance) are the most saturated colors. In contrast, white light (which has maximal variance) is the least saturated.

- Mean wavelength determines hue.

- This is simple for light that’s normally distributed across the spectrum, but once this restriction is relaxed things get very complicated very quickly.

- E.g. We can’t predict the perceived color of a surface from only knowing the spectrum of light being reflect from it because of the surrounding surfaces, lighting conditions, orientation of the surface, and shadows.

Section 3.2: Image-Based Color Processing

- It isn’t clear nor confirmed if color is represented at the level of a 2D image.

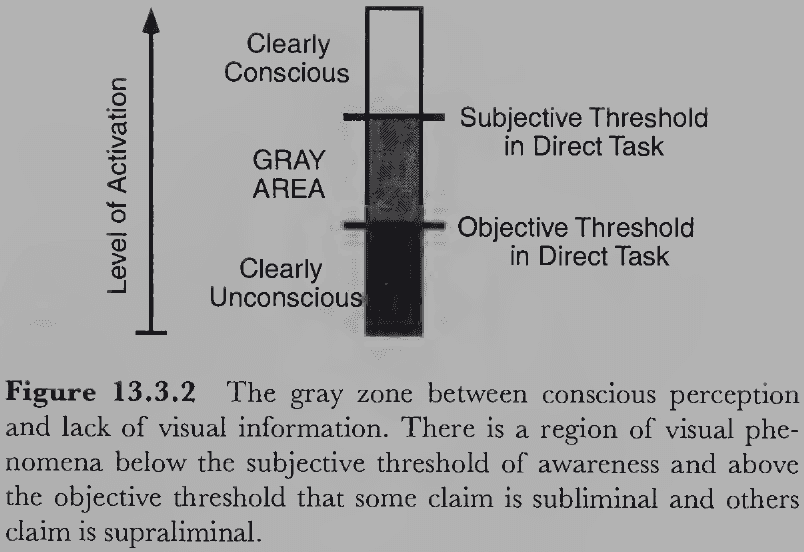

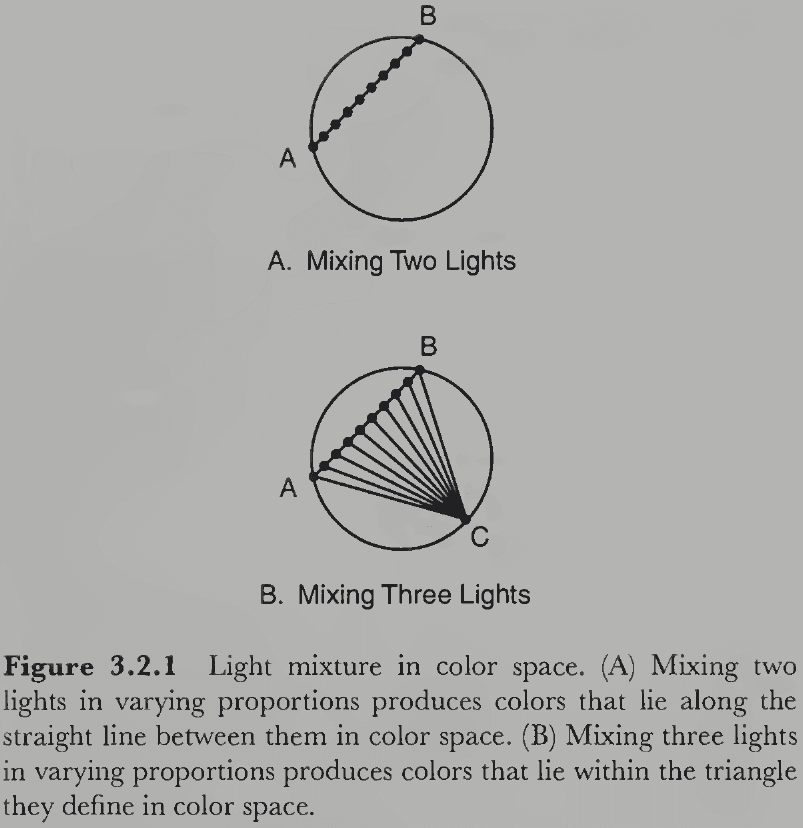

- Many phenomena discovered more than a century ago helped us better understand color perception.

- E.g. Color mixture, types of color blindness, color afterimages, existence of induced colors, chromatic adaptation.

- Light mixture

- Only a small fraction of colors in the color space are monochromatic lights.

- Nonspectral colors (purples) and desaturated colors (pastels and grays) are when two or more different wavelengths are mixed.

- How do colors combine?

- It depends on whether one mixes light or paint.

- For mixing light, it’s simple. When mixing light A with light B, the resulting color lies on the line connecting A and B in color space, depending on the proportions of A and B.

- E.g. For lights of complementary colors, mixing them produces achromatic/white light because they’re on opposite sides of the color circle and the line crosses the center point.

- If three colors are mixed, then the resulting color lies on the triangular plane connecting A, B, and C.

- E.g. If red, blue, and green are mixed, then we can produce most of the colors in the color space by varying their relative amounts. Exceptions include highly saturated yellows, purples, and blue-greens.

- Metamers: pairs of lights or surfaces that look the same but have different physical spectra.

- The fact that just three lights can produce almost any hue is important for color technology.

- Color blindness

- This is a condition where a person can’t discriminate among certain colors.

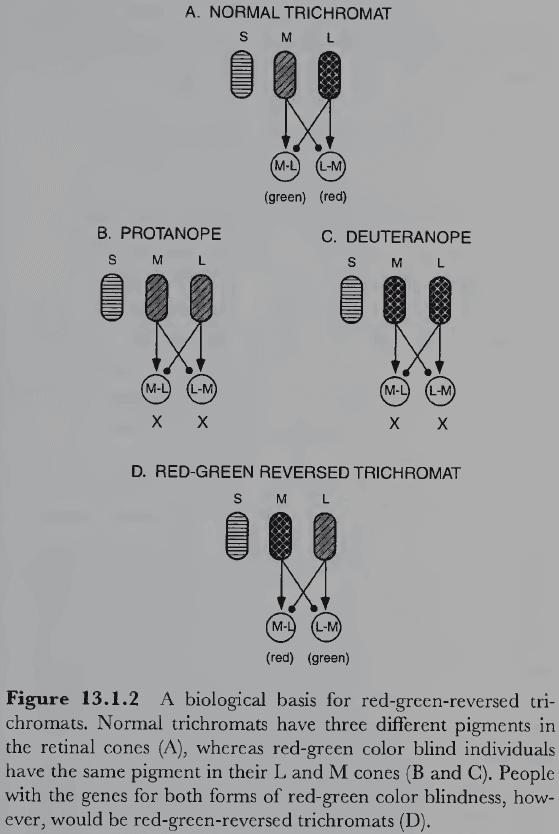

- Review of trichromats, dichromat, and monochromats.

- Three types of dichromats

- Protanopia: red/green color blind with a neutral point of 492 nm.

- Deuteranopia: red/green color blind with a neutral point of 498 nm.

- Tritanopia: blue/yellow color blind with a neutral point of 570 nm.

- Why do these particular forms of color deficiencies exist and no others? We’ll find the answer in physiology.

- Color afterimages

- There are aftereffects when viewing highly saturated colors for long periods.

- E.g. Each hue produces its complementary hue in the afterimage such as green with red, black with white, and yellow with blue.

- To determine the complement of a color, just stare at a highly saturated patch of it and then look at a sheet of white paper. Your visual system automatically gives you the answer.

- Simultaneous color contrast

- When two regions of identical spectra are perceived differently due to the spectra of surrounding regions.

- Chromatic adaptation

- Since the visual system adapts to both light and dark conditions, it isn’t surprising that it also adapts to chromatic conditions (prolonged exposure to color).

- Chromatic adaptation is eye-specific.

- There’s a close relation between adaptation and aftereffect as chromatic adaptation causes chromatic aftereffects of the complementary hue. However, they aren’t the same.

- Adaptation is the lowering of sensitivity after prolonged stimulation, while aftereffect is the experience of an opposite perception after prolonged stimulation.

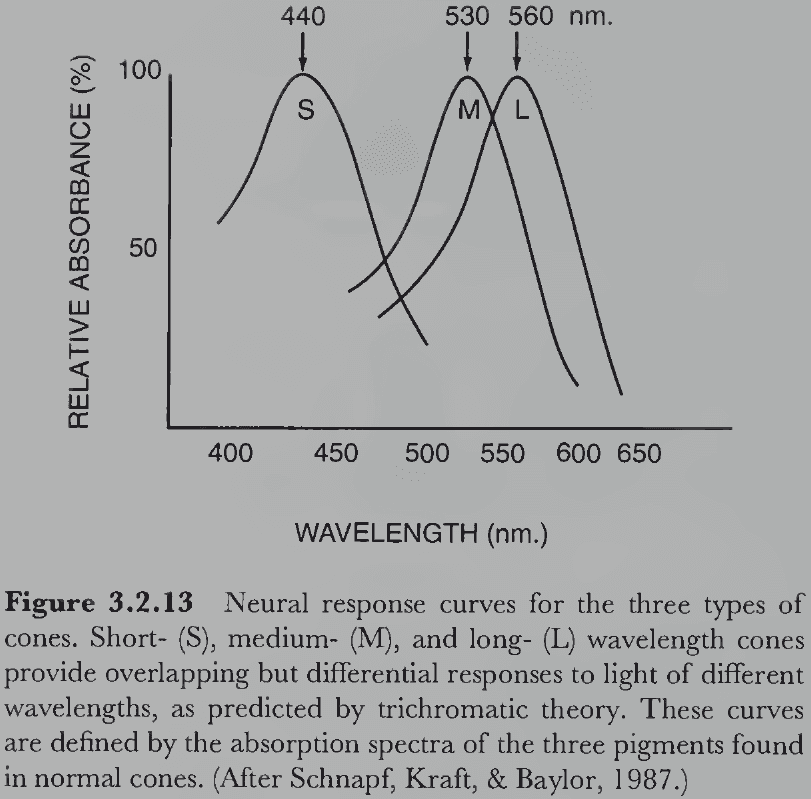

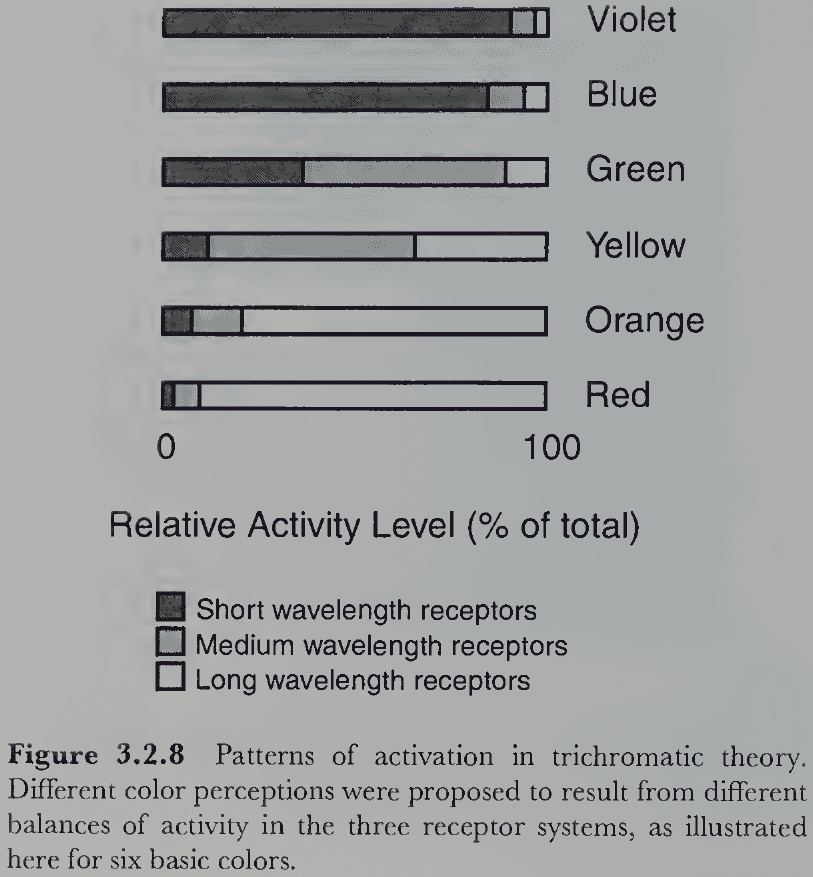

- Trichromatic theory

- Hypothesized that there are three types of color receptors that produce the psychologically primary color sensations of red, green, and blue.

- All other colors are combinations of these primaries.

- The three types of receptors respond differently to different wavelengths of photons.

- E.g. Short wavelengths for blue, medium wavelengths for green, and long wavelengths for red.

- Each receptor’s sensitivity to wavelength overlaps and any given wavelength stimulates the three-receptor system to different degrees.

- Thus, the pattern of activation across the three receptor types determines the perceived color.

- This theory accounts for many important phenomena of color vision.

- E.g. The three dimensions of color space match the existence of the three types of receptors. Metamers are explained as the same pattern of activation produced by many physically distinct combinations of wavelengths. Color blindness is explained as the absence of one of the receptor types.

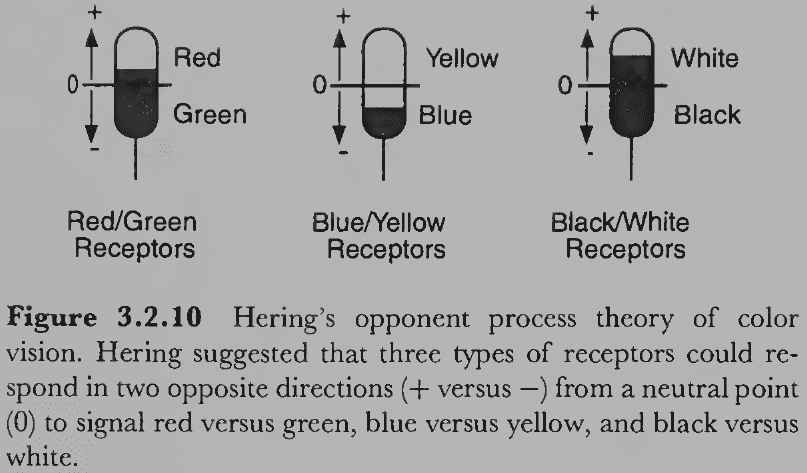

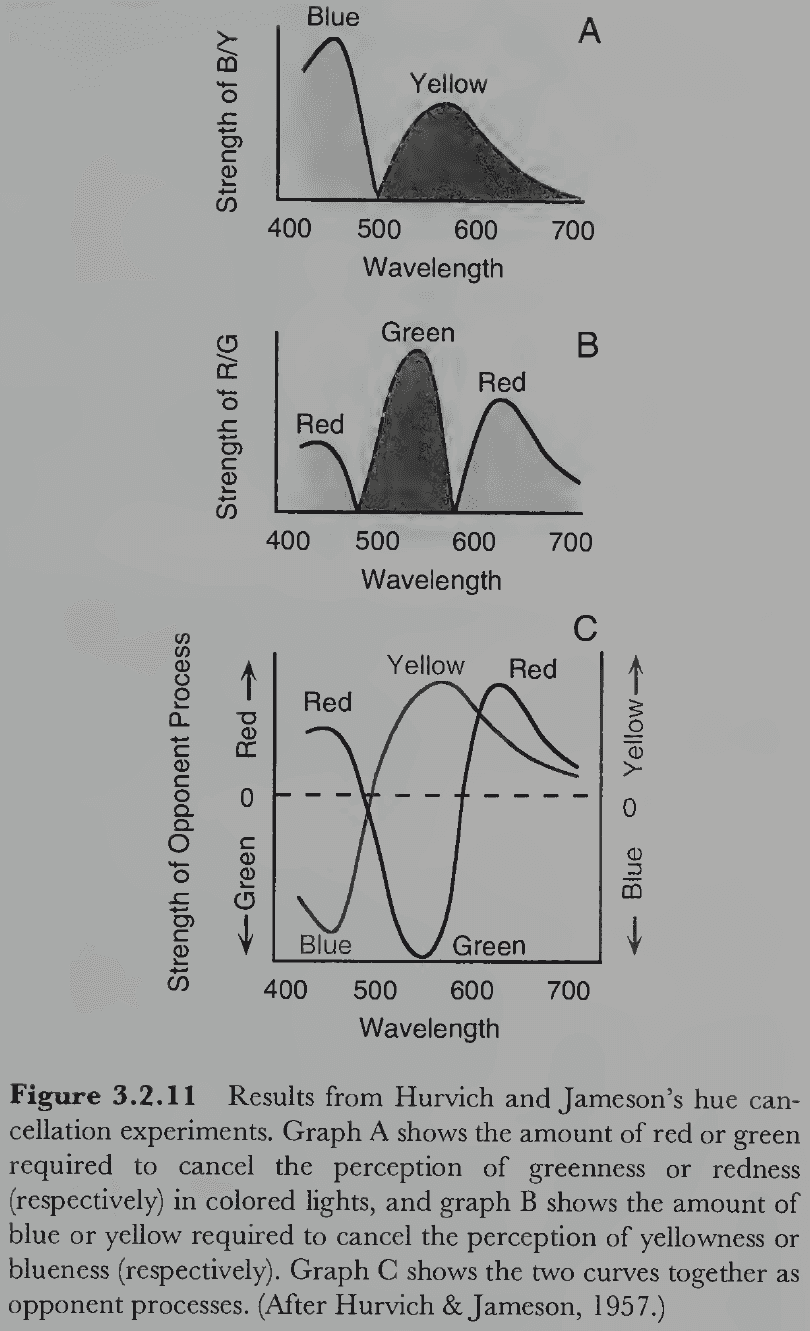

- Opponent process theory

- Although the trichromatic theory explains many phenomena, it doesn’t explain the nature of people’s subjective color experiences.

- E.g. Why are color experiences always lost in certain pairs? Such as red and green, or blue and yellow.

- Colors are never lost independently nor are they lost in other pairings such as red and blue, or green and yellow.

- Another piece of evidence against the trichromatic theory is that colors other than the primary colors (red, green, blue) don’t subjectively look like a combination of the primary colors, but instead look primary themselves.

- E.g. Yellow doesn’t look like a mixture of red and green, it looks like yellow. Yellow seems to be psychologically just as “primary” as red, green, and blue.

- Furthermore, evidence for polar opposites among colors comes from color afterimages and induced colors.

- From this, we hypothesize that there are four chromatic primaries rather than three and that they’re structured in pairs of opposites: red versus green, and blue versus yellow.

- Dual process theory

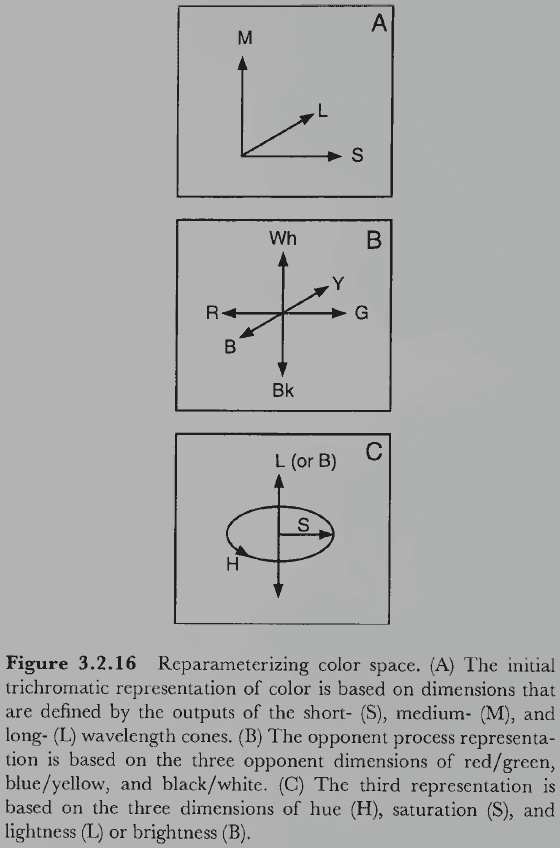

- We can combine the trichromatic and opponent process theories into a two-stage theory of color vision called dual process theory.

- Both theories are correct, but for different stages of visual processing.

- Both stages of the dual process theory are now known to occur in the retina but importantly, the theorizing was done before the relevant physiology was known.

- This was, in part, due to technological limitations as it was easier to perform behavioral experiments than to dissect the retina.

- Another factor is that it’s generally easier to work from the abstract functional level downward to the physical implementation than in the reverse direction.

- As predicted by the trichromatic theory, there are three types of cones in the retina that each contain a different light-absorbing pigment.

- E.g. Short-wavelength (S), medium-wavelength (M), and long-wavelength (L) cones.

- The ratio of L to M to S cones appears to be nonuniform at about 10:5:1 with the receptors in the central 0.1 degree of the fovea being almost exclusively M and L cones.

- These three cone types, sometimes misleadingly called blue, green, and red cones, work as predicted by the trichromatic theory and explains some cases of color blindness.

- E.g. Protanopes are missing L cones, deuteranopes missing M cones, and tritanopes missing S cones.

- Responses in the LGN of macaque monkeys were incompatible with the trichromatic theory but conformed to the opponent process theory.

- E.g. Some cells were excited by red light and inhibited by green light and vice versa. Same applies to blue and yellow, and to light and dark.

- Further research has found this pattern of response in the bipolar and ganglion cells of the retina.

- How are the opponent responses of these cells derived from the outputs of the three cones system? We don’t know with certainty.

- Although the dual process theory is elegant and accounts for most color phenomena, it isn’t perfect.

- E.g. It isn’t clear why the shortest wavelengths of the spectrum (violet) appear reddish.

- The two initial steps in color processing are an example of how an information processing system starts with one representation and transforms it into another representation.

- Assuming that there’s a later cortical representation of color in terms of hue, saturation, and lightness, the red/green and blue/yellow axes must be further transformed.

- The effect of these transformations is to reparametrize the 3D color space so that different, evolutionary more useful, information is made explicit in successively higher levels of representation.

- Reparameterization: the process of changing the variables that directly control a system’s behavior.

- E.g. Your bathroom faucet transforms the 2D control system of hot or cold water and how much into one control function, like back and forth for volume and left or right for temperature.

- Why does the visual system use three different color representations?

- E.g. Hue, saturation, and lightness.

- Because different representations provide information that’s useful for different purposes.

- To understand brightness contrast and simultaneous color contrast effects, we need some kind of spatial interaction between neighboring regions of the retina.

- Lateral inhibition: when neurons are spatially organized to inhibit neighboring neurons.

- Interestingly, a lateral inhibitory network has a pattern of outputs similar to the Mach band phenomenon.

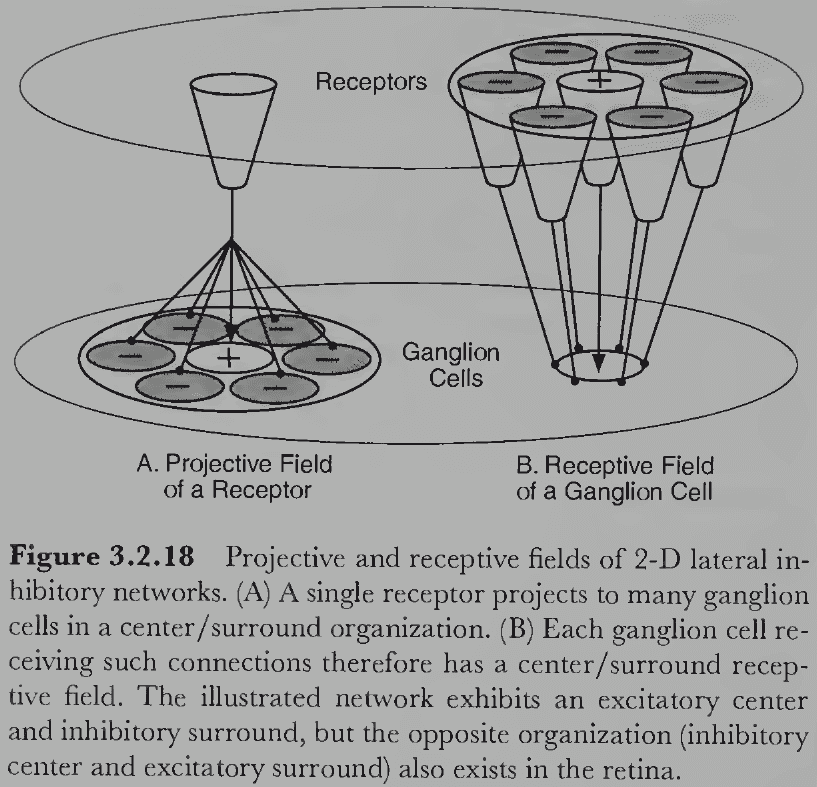

- Review of projective and receptive field.

- For a 2D lateral inhibitory network, a center-surround organization emerges where cells respond maximally to a pattern of a bright spot activating its excitatory center and a dark ring surrounding the center.

- The ganglion cells of many mammalian retinas have a center-surround organization.

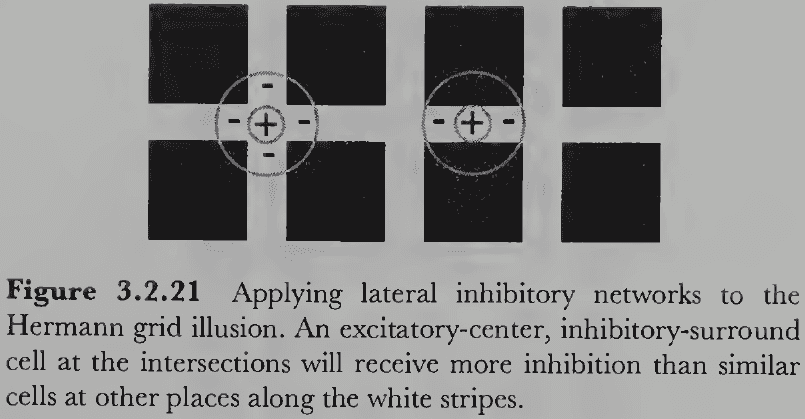

- The lateral inhibition theory explains the Hermann grid illusion as the intersections receive more inhibition causing the illusory dark spots.

- However, lateral inhibition doesn’t explain why the same colored shape on a black or white background appears darker or lighter respectively.

- Adaptation reduces sensitivity to light after prolonged exposure to an unchanging stimulus by temporarily depleting resources in the visual system. The reverse happens in dark environments.

- Over time, the activity of the visual system shifts away from the perception of the adapting stimulus.

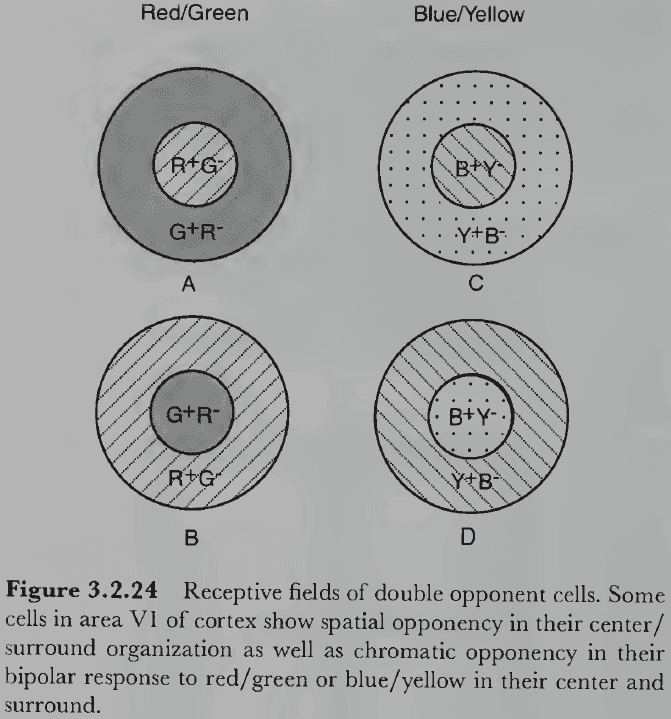

- Double opponent cells: cells in the visual cortex that have an opponent center-surround organization and provide the basis for simultaneous color contrast effects.

- E.g. A red/green double opponent cell would be excitatory to red and inhibitory to green in the center, and excitatory to green and inhibitory to red in the surround.

- This applies to red/green, blue/yellow, and white/black opponent cells.

- Double opponent cells explain why a gray circle on a highly saturated green background appears pinkish; its because the surrounding green region falls on the red/green double opponent cells, causing it to inhibit the center thus signaling red and giving the gray circle a reddish tint.

- Achromatopsia: inability to see color due to cortical damage and not retinal damage.

- Achromatopsia differs from color blindness because it isn’t caused by the lack of one or more cone types, instead the problem lies with the brain.

- Color anomia: inability to produce linguistic labels for colors.

- Color anomics can see colors perfectly well since they can discriminate and match them, but they can’t associate between perceived colors and their linguistic labels.

- Since color vision is genetically determined, how early do babies begin to perceive color?

- Evidence from preferential-looking-paradigm experiments suggest that two-month-old babies have normal trichromatic vision.

Section 3.3: Surface-Based Color Processing

- Our image-based description of color processing is only a rudimentary beginning of an explanation of real-world color perception because it fails to account for what we perceive.

- The “color” of a surface is a psychological property attributed to an external object and not a physical property of surfaces or light.

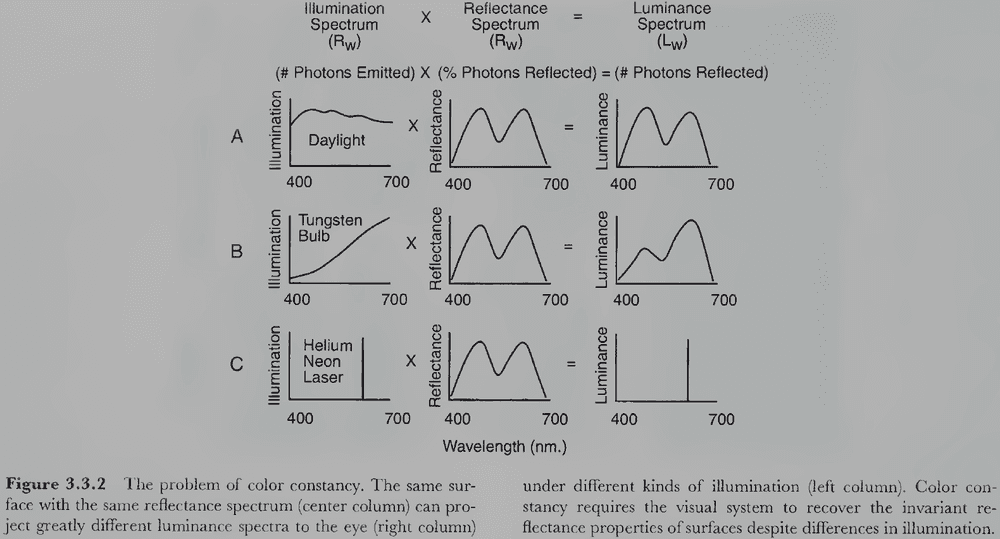

- The physical attribute that mainly determines the color of a surface is its reflectance spectrum.

- Reflectance spectrum: the percentage of incident light reflected at each wavelength.

- The reflectance spectrum (reflectance) of a surface is invariant because it doesn’t change under different lighting or viewing conditions. It always reflects the same proportion of light at each wavelength independent of the illumination.

- Luminance spectrum: the light that falls on the retina.

- The problem the visual system faces in perceiving surface color is that the luminance spectrum is determined both by the reflectance spectrum of the surface and the illumination spectrum of the light that strikes the surface.

- E.g. A red surface seen under a red light looks very different when seen under a green light.

- This is known as the color constancy problem.

- The visual system solves the color constancy problem by somehow disentangling the effects of reflectance and illumination so that the invariant property of surface reflectance can be perceived despite changes in illumination.

- This is the inverse problem for color and once again, the problem is underconstrained because the eye receives information about only one known variable (luminance) that’s determined by two unknown variables (reflectance and illumination).

- To recover reflectance from luminance, we believe that the visual system uses additional sources of information, probably in the form of clever heuristics and assumptions, to accomplish this task.

- Color constancy is a special case of perceptual constancy.

- Perceptual constancy: the ability to perceive the properties of environmental objects in spite of changing environmental conditions.

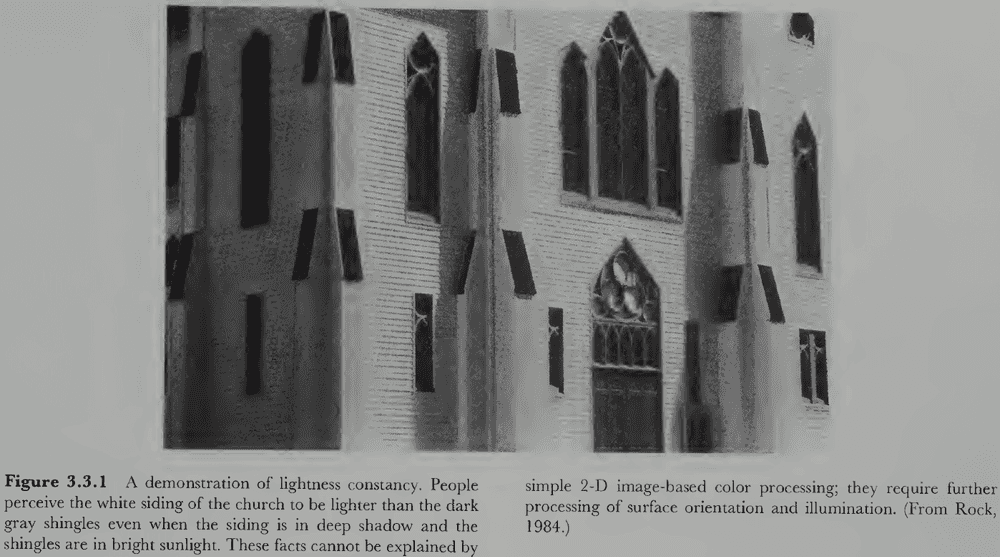

- Lightness constancy: perception of a achromatic surface as having the same surface lightness regardless of differences in illumination or viewing conditions.

- Adaptational processes are involved in lightness constancy, but it can’t account for all of it.

- Adaptation takes a relatively long time whereas lightness constancy is virtually immediate.

- E.g. If you’re reading a book and the light suddenly dims, your perception of the page doesn’t turn gray and then gradually lighten.

- One hypothesis is that perceived lightness depends on the relative luminance (contrast) between neighboring regions.

- The boundary between regions, the edge, determines the perceived relative lightness of the two regions. This then propagates across the entire region.

- Retinex theory: proposes that lightness depends on the global integration of locally determined luminance ratios at edges.

- No notes on the details of the retinex theory.

- Although the contrast between regions is useful, it doesn’t specify what scale to use.

- E.g. If a region reflects five times as much light as its background region, we don’t know whether the lighter region is white and its background is gray, or the lighter region is gray and its background is black.

- Scaling problem: how are luminance ratios mapped onto the white-to-black scale of achromatic lightness?

- The visual system appears to solve the scaling problem by using a simple anchoring heuristic by assuming the region with highest luminance is white and scaling all other regions accordingly.

- Experiments support this idea with darkish gray regions being perceived as white under specific conditions.

- Once again, this isn’t the full story though as regions with the highest luminance aren’t perceived as white, but instead as luminous or bright.

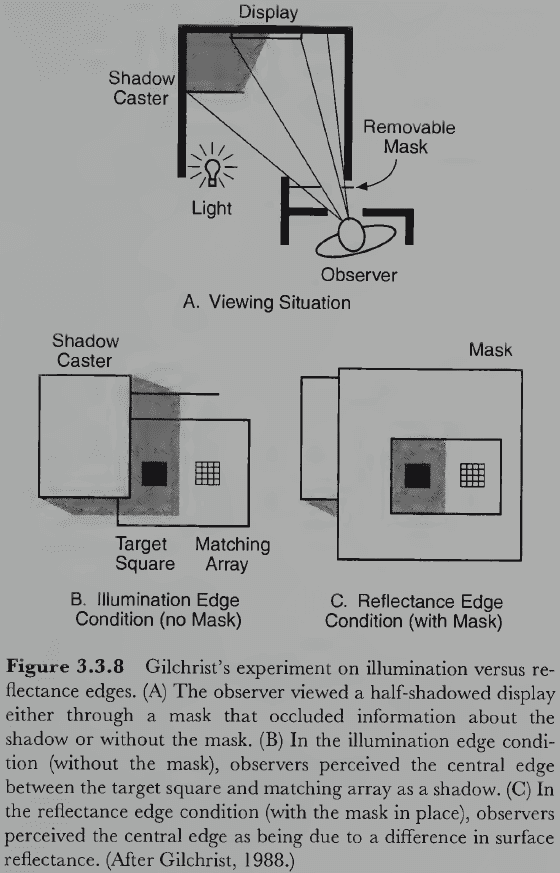

- Two kinds of edges

- Reflectance edges: changes in image luminance caused by changes in the reflectance of two surfaces.

- E.g. The edge between white and black paint.

- Illumination edges: changes in image luminance caused by different amounts of light falling on the surface.

- E.g. The edge between an object and a shadow.

- Reflectance edges: changes in image luminance caused by changes in the reflectance of two surfaces.

- How does the visual system determine whether an edge is reflectance or illumination?

- One factor is if the edge is fuzzy or sharp. Illuminance edges due to shadows tend to be fuzzy and graded whereas reflectance edges tend to be sharp.

- Another factor is depth. If depth information says that two regions don’t like in the same plane, the edge tends to be perceived as an illumination edge.

- A third factor is the magnitude of the luminance ratios at the edge. Illumination edges can produce much greater changes in luminance than reflectance edges.

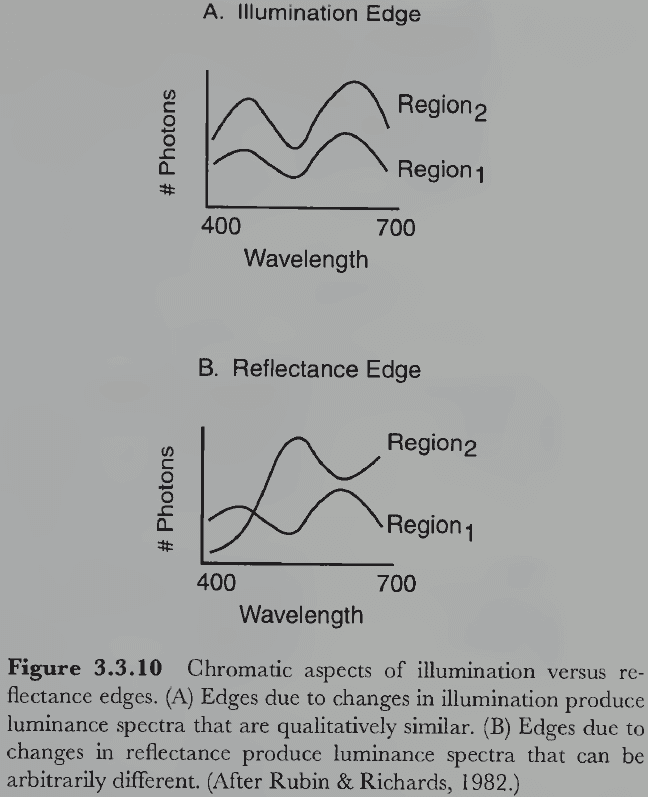

- Generally, if hue or saturation varies across an edge, it’s probably a reflectance edge. If only brightness varies, it’s probably an illumination edge.

- We can extend our facts and theories about achromatic constancy to colors.

- Chromatic color constancy: the perception of invariant properties of a surface’s spectral reflectance despite changes in illumination and viewing conditions.

- Objects appear to have the same color under different illumination, but different light sources can have substantially different illumination spectra, which causes different luminance spectra to the eye.

- Chromatic adaptation is believed to be important for color constancy.

- Human color constancy is remarkably good as we perceive mostly a surface’s reflectance spectrum even though the light entering the eye (luminance spectrum) is actually the product of its reflectance spectrum times the illuminance spectrum.

- The visual system is somehow able to separate out the wavelength information in the illuminating light from the wavelength information in the surface reflectance.

- Three constraints under natural viewing conditions

- Consistencies in the illuminating light within a scene.

- When the intensity of light is constant for parts of an image, it reduces the number of free parameters of the illuminance spectrum down to three for that part of the image.

- For this to work though, the visual system must somehow discriminate between illuminant and reflectance edges.

- Restricted range of illumination spectra for normal illuminants.

- We don’t encounter all possible light sources under normal viewing conditions.

- Color constancy tends to fail when there are strongly chromatic light sources, but we rarely encounter these outside of stage lighting and perceptual experiments.

- Restricted range of reflectance spectra.

- We also don’t encounter all possible surface reflectance spectra either.

- Consistencies in the illuminating light within a scene.

- If color vision evolved to allow organisms to perceive the reflectance of surfaces as approximately constant over variations in normal daylight, then one method is to remove these variations by a compensatory internal process.

- E.g. The black/white, red/green, and blue/yellow structure of color vision may be an evolutionary adaptation to compensate for changes in normal daylight.

- But this conjecture is speculative and doesn’t have any evidence supporting it.

- We now revisit how the visual system distinguishes between illumination and reflectance edges.

- Illumination edges have similar chromatic aspects while reflectance edges have different chromatic aspects.

- We aren’t certain, but maybe the visual system uses the red/green and blue/yellow opponent systems to compare the chromatic aspects of two regions. If they’re similar, this suggests a reflectance edge. If they’re different, an illumination edge.

- Color constancy doesn’t seem to be an innate ability because two-month-old infants looked at the same stimulus with different illumination for the same amount of time as they did a new stimulus.

- In contrast, four-month-old infants looking at the same stimulus with different illumination looked away as fast as the same stimulus with same illumination. This matches what we’d predict with color constancy.

Section 3.4: The Category-Based Stage

- The processing of color isn’t complete when we can internally represent a colored surface.

- The next step is to classify colors and attach linguistic labels to them.

- E.g. Blood, tomatoes, and certain apples are all classified as red even though they produce unique hues, saturations, and lightnesses.

- People divide the continuous 3D space of color into discrete color categories.

- Evidence supports the view that the fundamental color categories are primarily determined by the physiology of the human visual system.

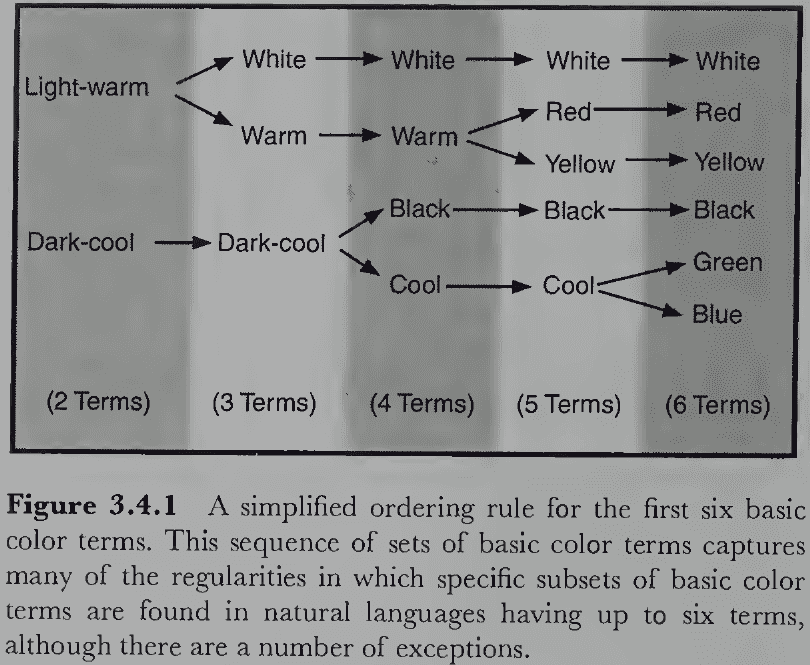

- How are colors named?

- The first breakthrough came from cross-cultural research on color naming.

- E.g. How people in different cultures with different languages apply labels to colors.

- Review of cultural relativism and the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

- It seems that if a language has only two basic color terms, the terms will always be light-warm and dark-cool. If three, then add white and so on, each time adding the next basic color term.

- The regularity and pattern that languages follow when developing and adding new color terms undermines the cultural relativity hypothesis and suggests an alternative hypothesis.

- Linguistic universality: the idea that language is determined either by invariant physical characteristics in the structure of the environment or by invariant biological features in the structure of the organism, or both.

- For color naming, the evidence strongly favors biological determination.

- E.g. Is it a coincidence that the first six names for colors in any language match the three opponent processes (black/white, red/green, blue/yellow)?

- The compelling conclusion from this research is that the fundamental structure of color naming is fixed by genetically determined physiology.

- Color classification may be structured around a focal/best-example color rather than class boundaries because people more quickly and reliably picked out the focal colors than color boundaries.

- The idea that color categories are based on prototypical examples received further supported from studies on colors naming in tribes and from studies on the speed of classifying focal versus non-focal colors.

- Focal colors serve as cognitive reference points for color categories and other colors are learned relative to them.

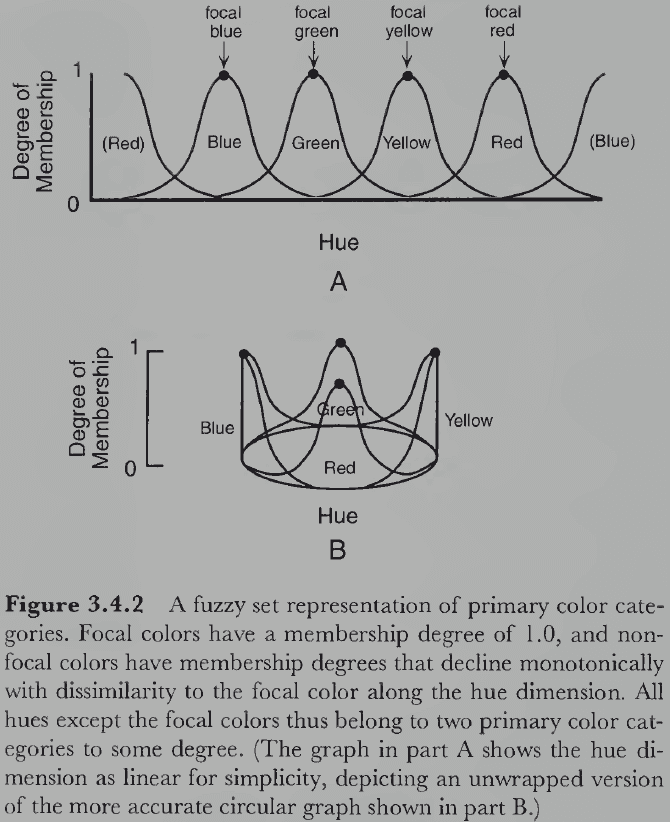

- No notes on fuzzy set theory applied to color naming.

- The fuzzy logical model of color categories is consistent with a large number of findings in human color naming and categorization research.

Part II: Spatial Vision

Chapter 4: Processing Image Structure

- Perceiving color is only one of our many visual abilities.

- An arguably more important ability is the perception of spatial structure.

- E.g. The shape, location, size, and orientation of objects in space.

Section 4.1: Physiological Mechanisms

- We start with trying to understand how spatial processing occurs in the retina.

- Review of on-center off-surround, and off-center on-surround ganglion cells (cells that have an antagonism between an inner circle and surrounding ring).

- The area surrounding the central region always has the opposite characteristic.

- Although bipolar cells come before ganglion cells in the visual pathway, they were studied later because of technical reasons.

- Photoreceptors and bipolar cells respond by producing graded potentials.

- Graded potential: continuous changes in electrical potential that travel slowly and for short distances.

- In contrast to spikes that can be recorded inside or outside the cell, graded potentials can only be recorded from inside the cell.

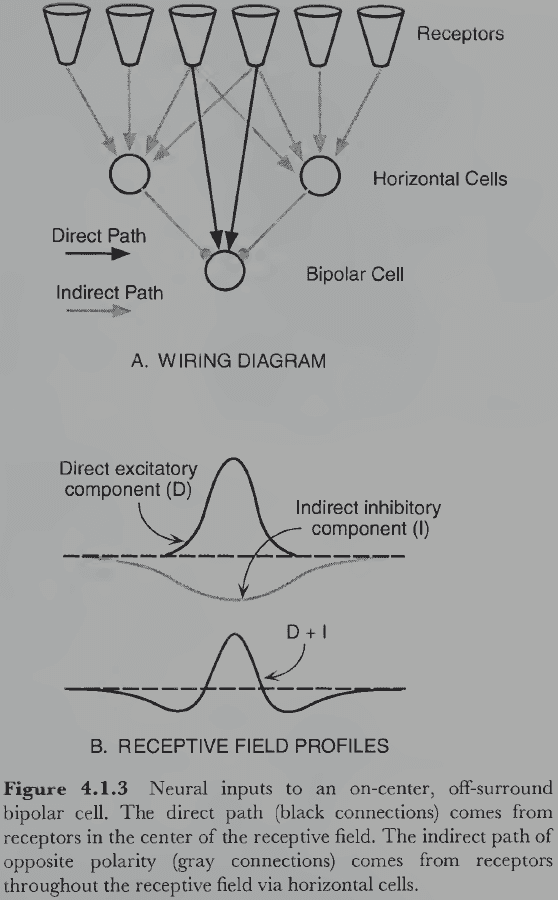

- Bipolar cells have similar receptive field properties as ganglion cells, namely the center-surround antagonist relation.

- This property is due to how the connections between photoreceptors and horizontal cells are organized.

- Photoreceptors are directly connected to bipolar cells but are also indirectly connected through the horizontal cells.

- The direct pathway is either excitatory or inhibitory but whatever it is, the indirect pathway is always the opposite.

- These two regions of excitation and inhibition sum in the bipolar cell to produce it’s center-surround receptive field.

- Lateral geniculate nuclei (LGN): cells in the thalamus that the retinal ganglion cells connect to.

- LGN cells have center-surround receptive fields like retinal ganglion cells but they’re larger with a stronger inhibitory surround.

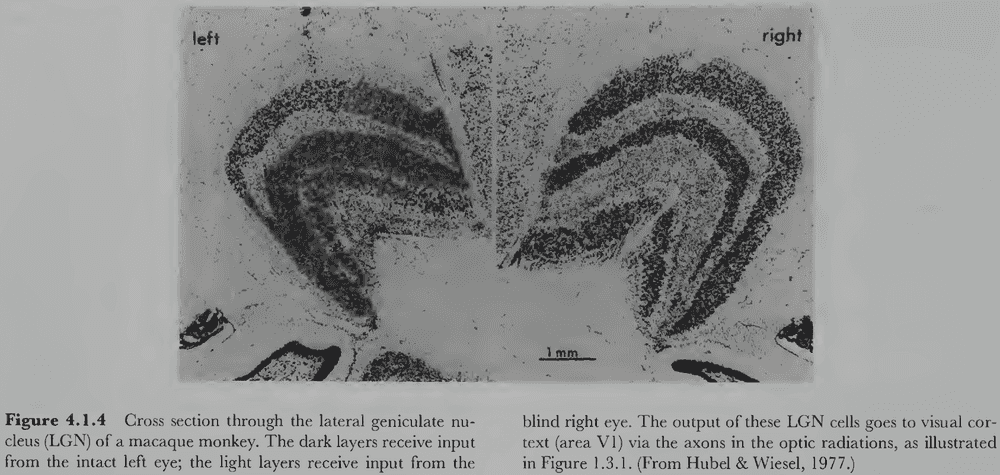

- One major difference between retinal ganglion cells and the LGN is their structure.

- E.g. The ganglion cells form a 2D sheet while the LGN is a 3D structure.

- Each LGN cell is monocular and only fires in response to stimulation from just one eye.

- Binocular cells aren’t present until the visual cortex.

- The internal architecture of the LGN is interesting and has provided important clues about a crucial functional distinction in the visual system.

- One clue is that the LGN is laminar/layered with six 2D sheets of neurons.

- The lower two layers are the magnocellular layers because they have large cell bodies, while the upper four layers are the parvocellular layers because they have small cell bodies.

- Magnocellular cells are sensitive to differences in contrast, are insensitive to color, have large receptive fields, and exhibit transient responses to changes in retinal stimulation.

- Parvocellular cells are insensitive to contrast, are sensitive to color, have small receptive fields, and exhibit sustained responses to changes in retinal stimulation.

- These distinctions aren’t clear-cut and there’s substantial overlap between magno and parvo cells.

- Perhaps the magno cells are specialized for processing motion and depth, while the parvo cells are specialized for processing color and shape.

- Backtracking, two different kinds of ganglion cells project selectively to the magno and parvo cells in the LGN: the M and P ganglion cells respectively.

- P cells receive input only from cones but M cells receive input from both rods and cones.

- We’ll see how the division between the M and P pathways propagates to higher levels of the visual system.

- Each LGN layer receives signals from just one eye with the four parvocellular layers alternating between the left and right eye. The same applies to the two magnocellular layers.

- Each LGN layer is also spatially organized like the retina it receives input from.

- Retinotopic mapping: when the organization/map of the relative location of cells on the retina is preserved.

- E.g. Nearby retinal regions project to nearby LGN regions.

- Retinotopy is a common feature of the visual nervous system.

- Striate cortex: a 2 mm thick sheet of neurons and a few square inches in surface area that’s the largest cortical area in primates.

- Review of Hubel and Wiesel’s discovery of the striate cortex neuron’s receptive fields.

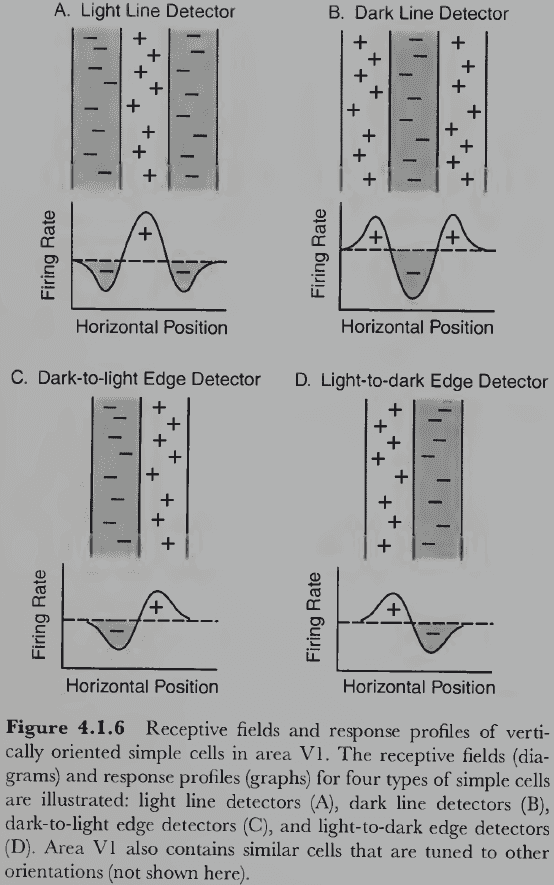

- Simple cells: neurons sensitive to a edge/line at a specific retinal position and orientation; often called edge/line detectors.

- Edges cells have an area of excitation on one side and an area of inhibition on the other, while line cells have an central elongated region of either excitation/inhibition and an antagonistic region on both sides.

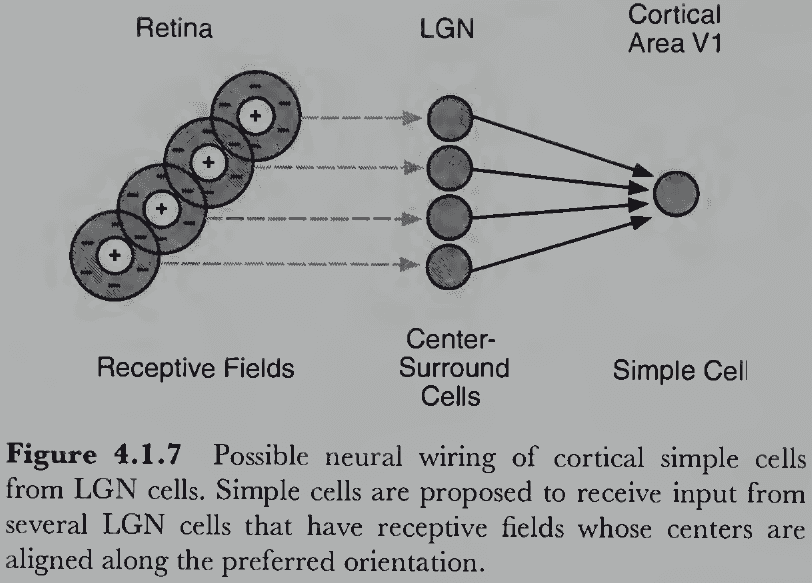

- It’s plausible that if LGN cells are wired in a specific way, we get edge and line detectors.

- Unique features of complex cells compared to simple cells

- Nonlinear: rarely responds to small stationary spots of light.

- Motion sensitive: highly responsive to moving lines/edges in a specific direction.

- Position insensitive: small differences in stimulus position won’t affect response rates.

- Spatial extension: tend to have large receptive fields.

- About 75% of the cells in the striate cortex are complex cells.

- Complex cells might emerge by integrating the responses of many simple cells.

- How is the striate cortex organized given that cells are tuned to different properties of the stimulus? Is it a crazy-quilt pattern with no discernable structure or are their regularities?

- Difficult experiments were performed that discovered truly remarkable regularities.

- The striate cortex in each hemisphere processes exactly half of the visual field and maintains retinotopy.

- The retinotopic map is distorted though because of cortical magnification.

- Cortical magnification: an increase in area devoted to processing a region of retina that has more photoreceptors (and thus is more evolutionarily important).

- E.g. A small area of the retina near the fovea occupies a disproportionately large area of cortex.

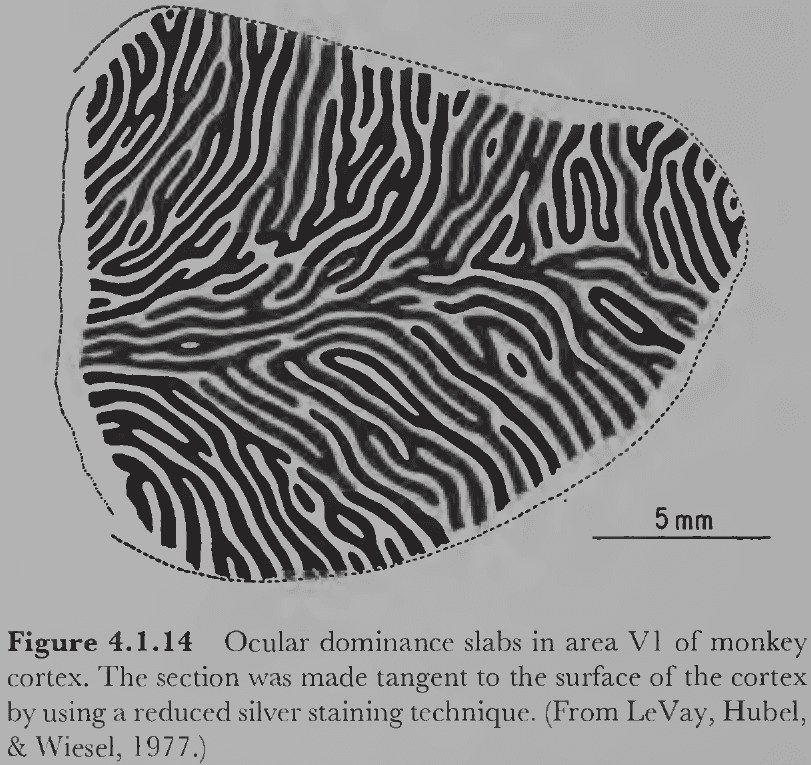

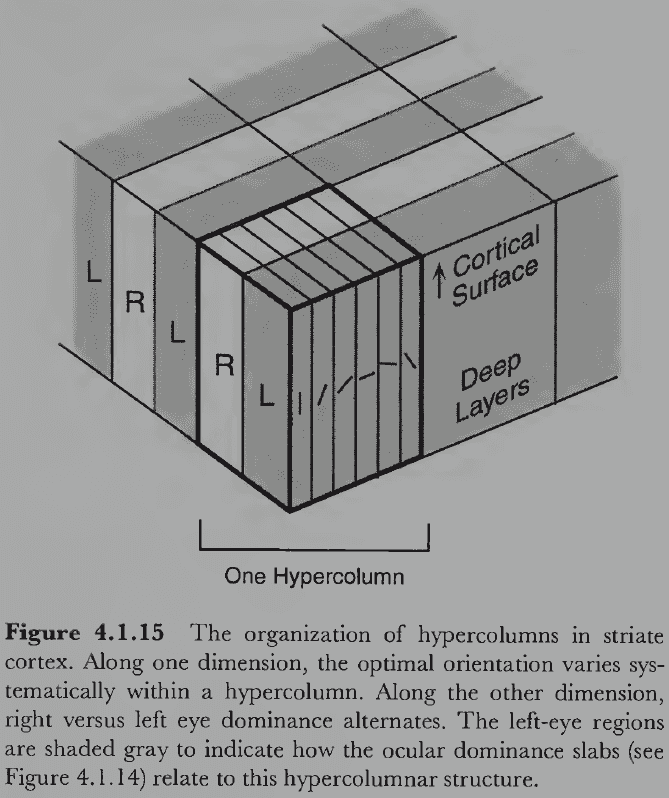

- Since both eyes project to both hemispheres, are there two separate retinotopic maps in the cortex or a single integrated one?

- The answer lies somewhere in between as there’s a global map for each cortex, within which cells dominated by one eye versus the other eye are interleaved.

- This results in ocular dominance slabs/columns; areas of cortex dominated by one eye.

- Hypercolumn: a column of cortical tissue that runs perpendicular through all six cortical layers.

- No notes on Hubel and Wiesel’s experiments on the development of cortical orientation cells in kittens.

- Critical period: a period of rapid development that depends on environmental stimulation.

- There are different critical periods for different visual properties but in general, it appears that the critical period for a given type of cortical cell depends on its level in the visual system.

- E.g. The critical period of lower-level cells occurs earlier than those of higher-level cells.

- This makes sense as higher-level cells can only develop their response properties after lower-level cells have developed theirs.

Section 4.2: Psychophysical Channels

- The discovery of simple and complex cells was controversial because there were disagreements over their functional significance.

- E.g. What are these cells doing?

- Unlike the study of color, the convergence between physiology and psychology in the study of spatial vision is weaker.

- The psychophysical community has been working within the spatial frequency theory, a theory that proposes a different conception of the cells Hubel and Wiesel discovered.

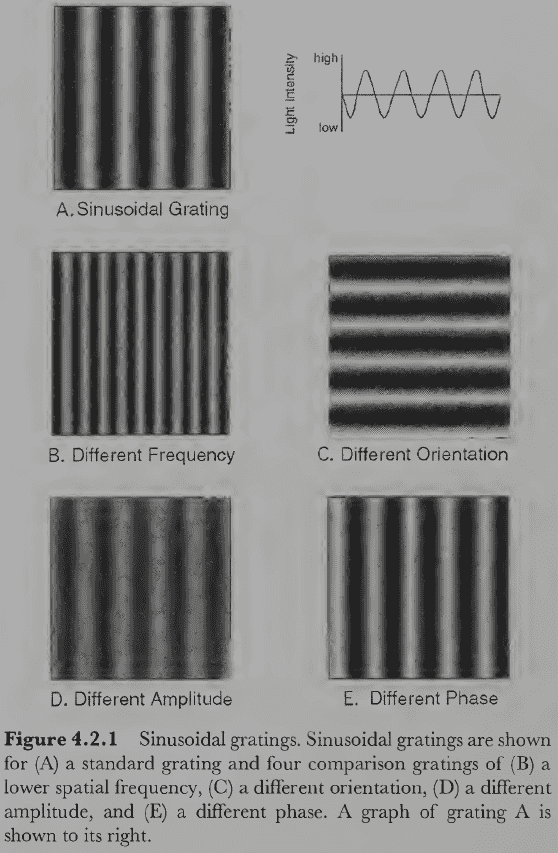

- Spatial Frequency Theory

- Instead of using edges and lines as the unit of vision, this theory uses sinusoidal grating.

- Sinusoidal grating: 2D patterns where luminance changes according to a sine wave.

- Each sinusoidal grating can be specified by four parameters: spatial frequency (width), orientation (angle), amplitude (contrast), and phase (position).

- It seems odd to use sinusoidal gratings as primitives because we don’t experience anything like them when looking at naturally occurring scenes, but there’s no reason to suppose that the primitive elements in early spatial vision are conscious.

- E.g. We don’t experience tiny points of color from the three cone types, we experience a uniform colored surface.

- One reason to use sinusoidal gratings is because they can be analyzed using Fourier analysis.

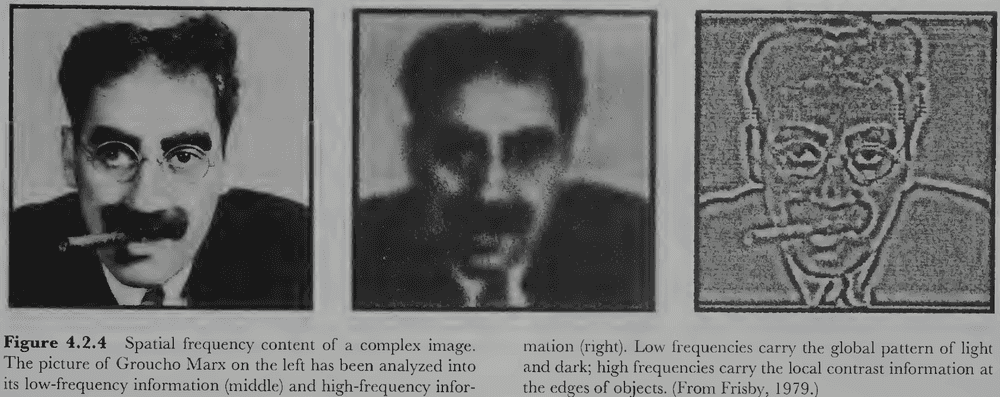

- Any 2D luminance image can be decomposed into the sum of a set of sinusoidal gratings that differ by spatial frequency, orientation, amplitude, and phase.

- The gratings with low spatial frequency tend to carry the image outline while the gratings with high spatial frequency tend to carry the image details.

- No notes on Fourier analysis power and phase spectrum.

- Fourier analysis provides a general method of decomposing complex images into primitive components.

- However, mathematical power and elegance alone aren’t convincing arguments that the visual system does anything like a Fourier analysis.

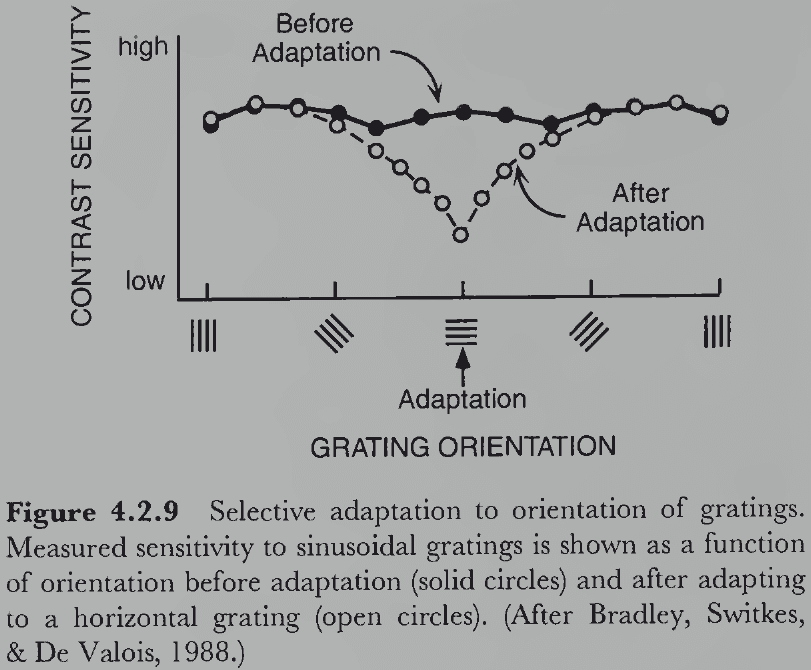

- Psychophysical channel: a hypothetical mechanism in the visual system that’s selectively tuned to a range of values within some continuum.

- Each channel is defined by the spatial frequency and orientation of gratings that it’s most sensitive to.

- So, the spatial frequency theory argues that image processing is understood as many overlapping psychophysical channels that are selectively tuned to different ranges of spatial frequencies and orientations.

- There is a great deal of evidence supporting this theory.

- E.g. When people stared at a sinusoidal grating for a long time, their visual system adapted only to that grating’s specific orientation and frequency and not to others.

- E.g. Discriminating between a sine wave grating and a square wave grating has the same contrast threshold as discriminating between a uniform field and a sine wave grating.

- It seems that infants are overall less sensitive to gratings and may only see a rough sketch of the image without its details.

- If psychophysical channels exist as suggested by these experiments, then they must be implemented somewhere in the visual nervous system.

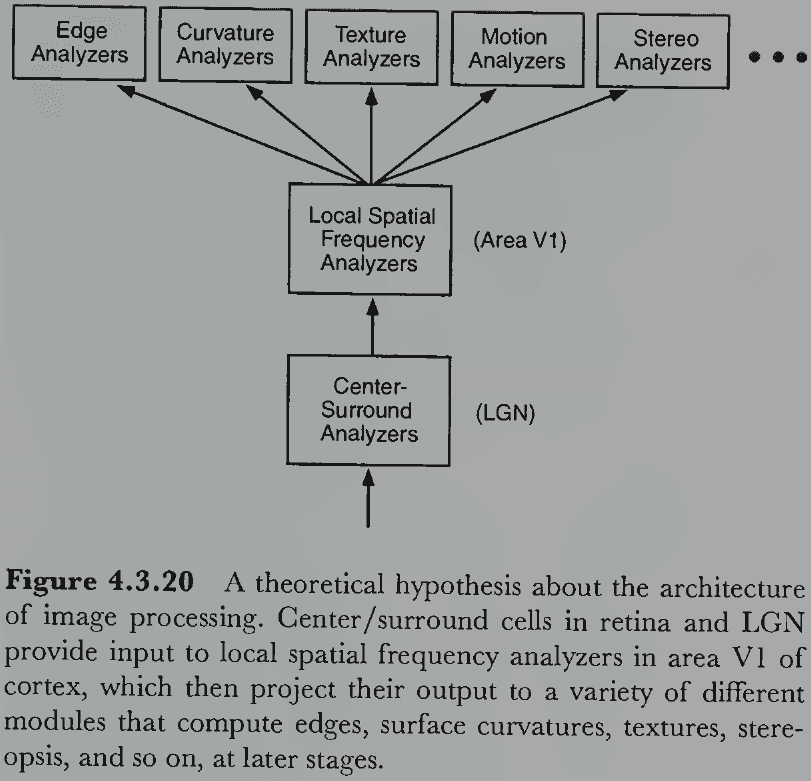

- Integrating the cells discovered by Hubel and Wiesel with the spatial frequency theory suggests that simple and complex cells perform local spatial frequency analysis.

- Local spatial frequency analysis can be achieved by using many small patches of sinusoidal gratings that fade out with distance from the center of the receptive field.

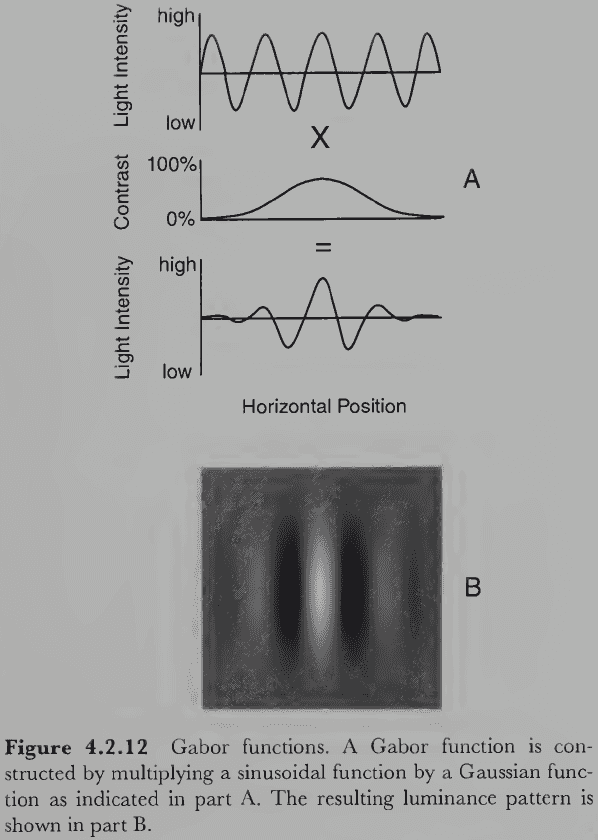

- This modified grating or receptive field is called a Gabor function or wavelet and is created by multiplying a sinusoidal grating with a bell curve.

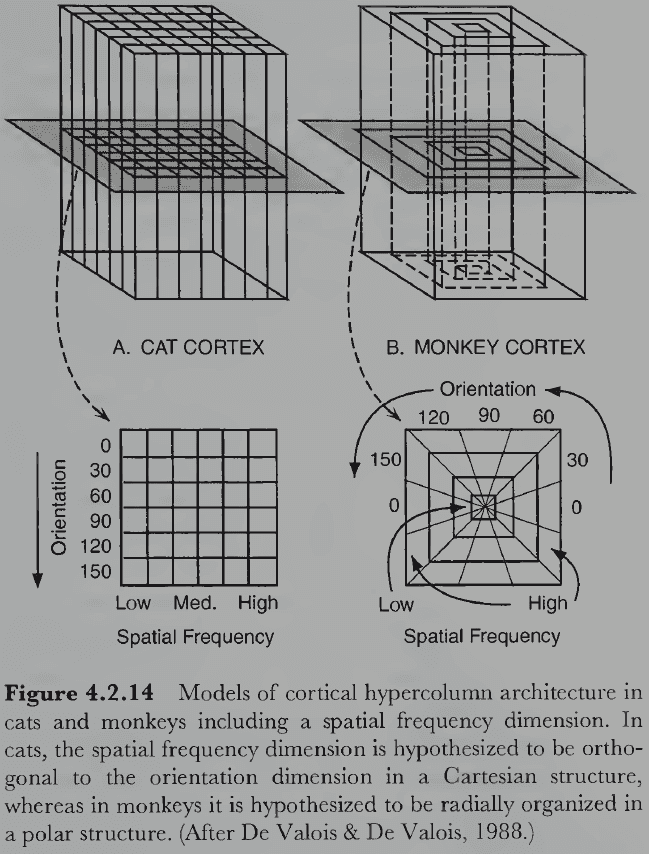

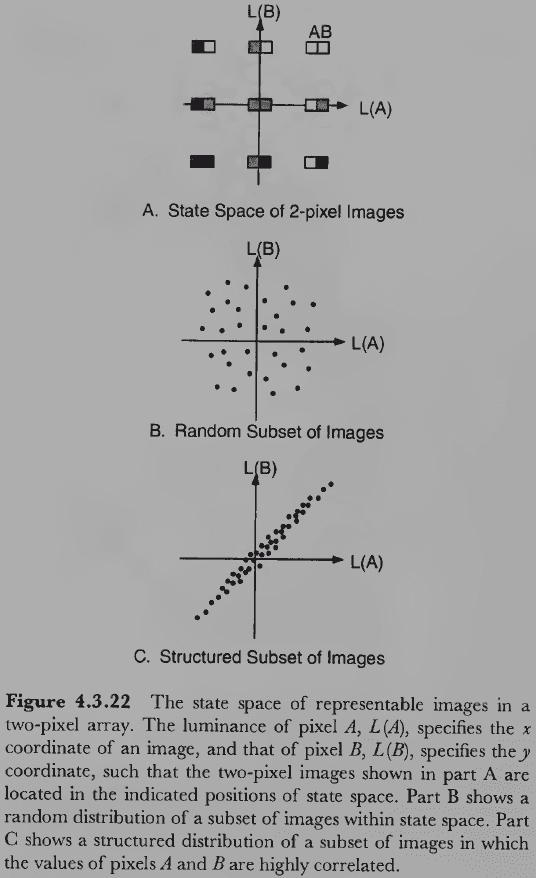

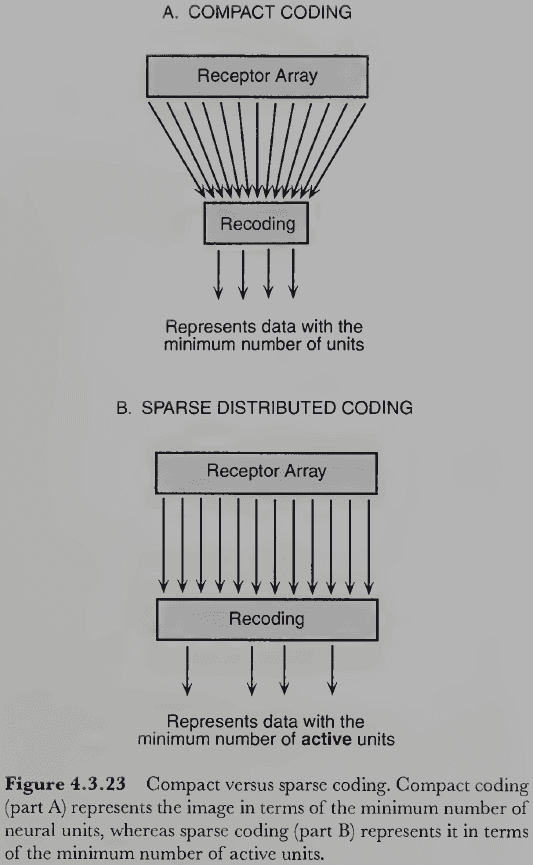

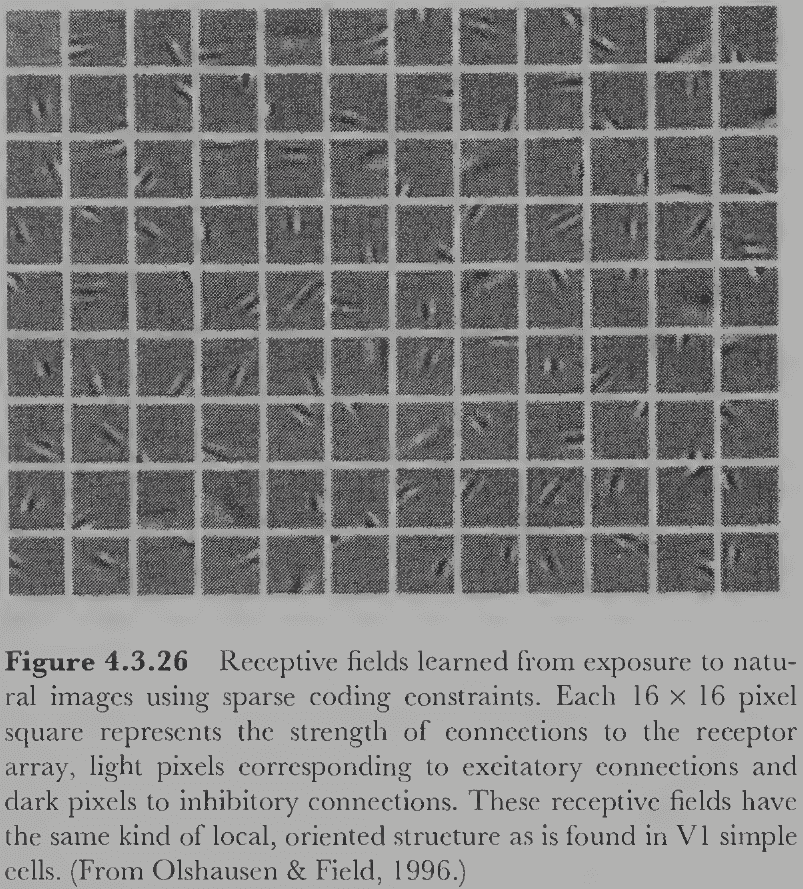

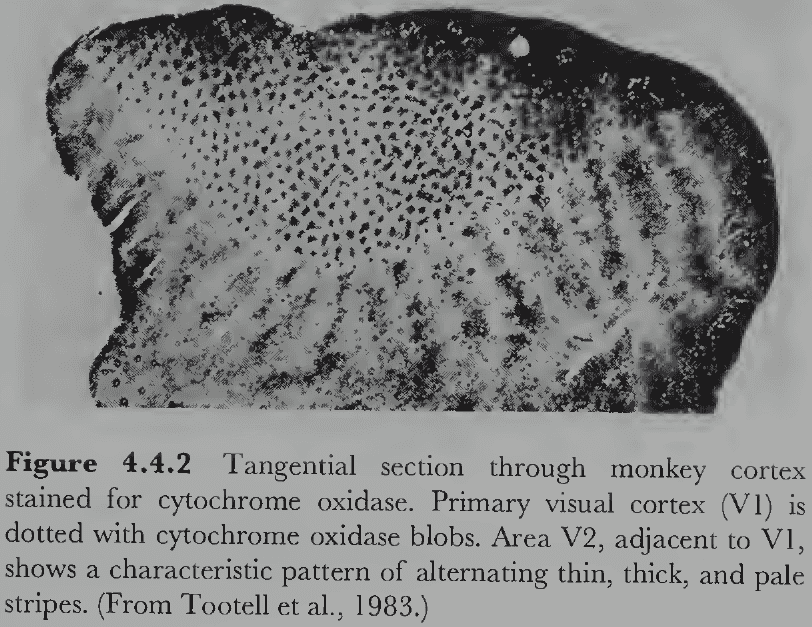

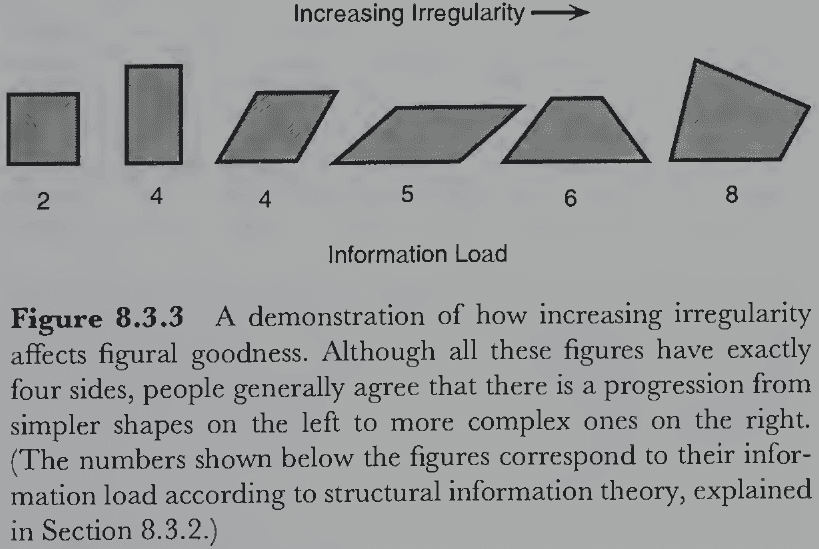

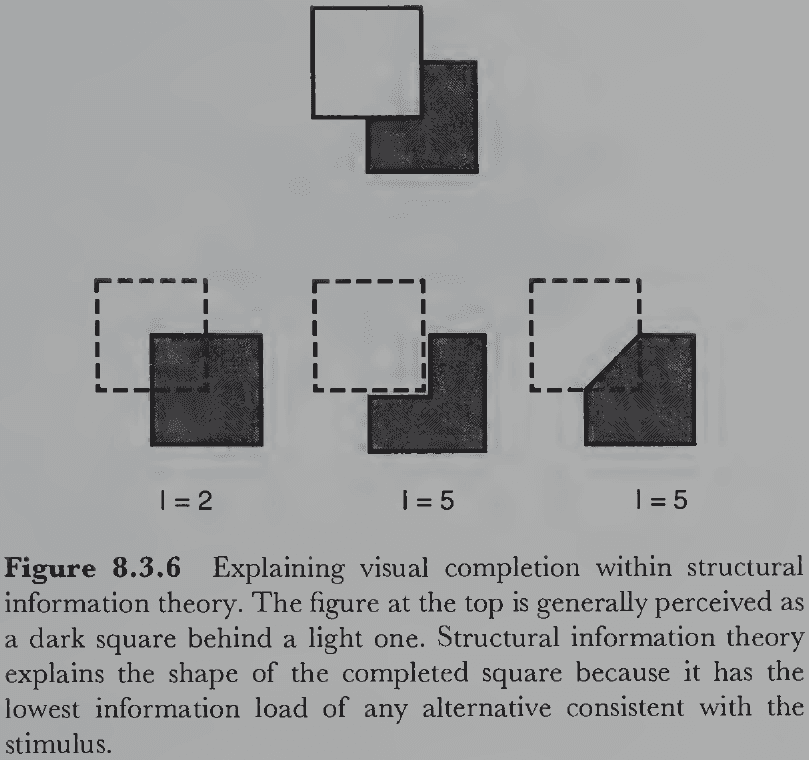

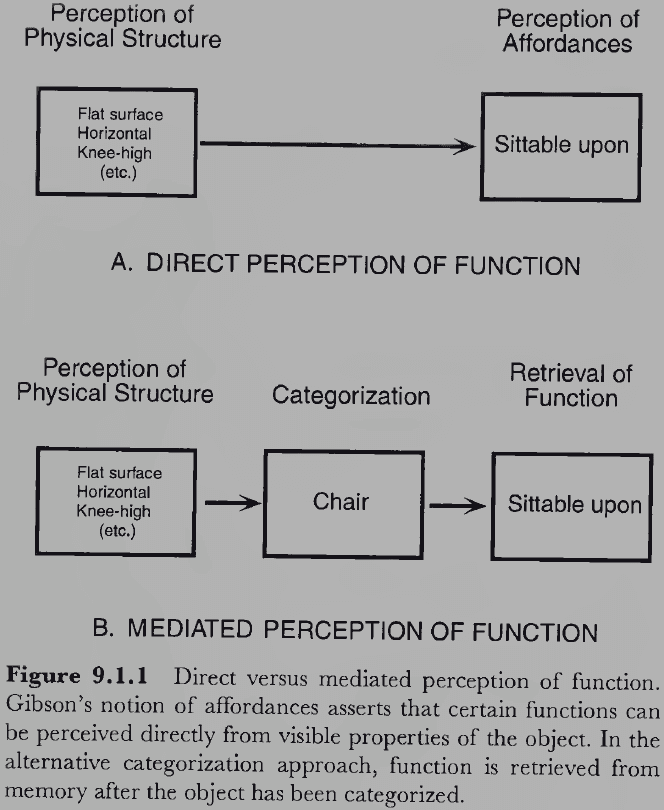

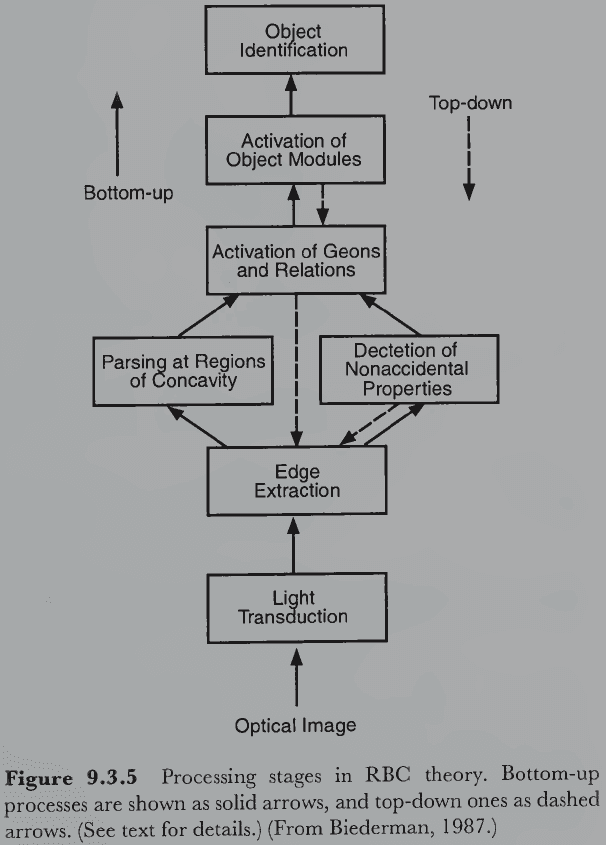

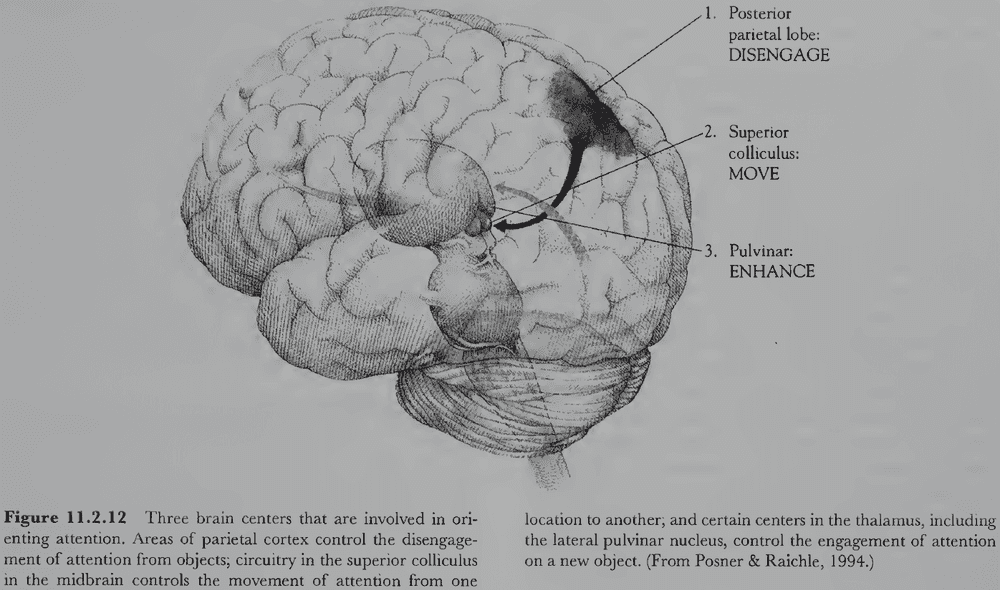

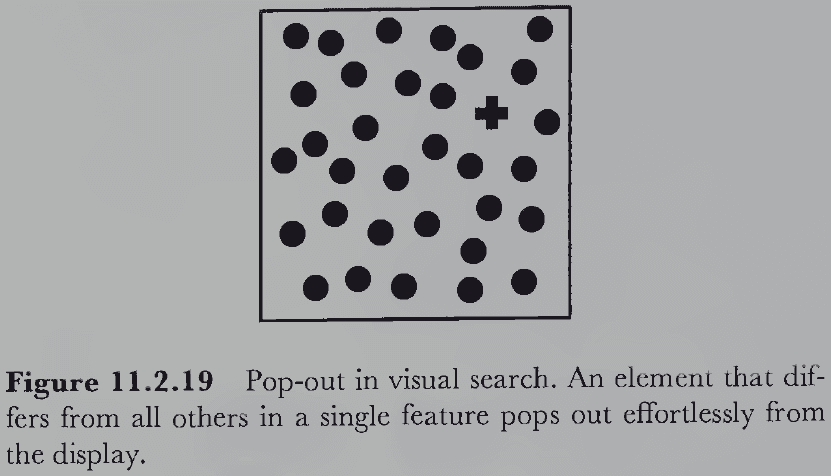

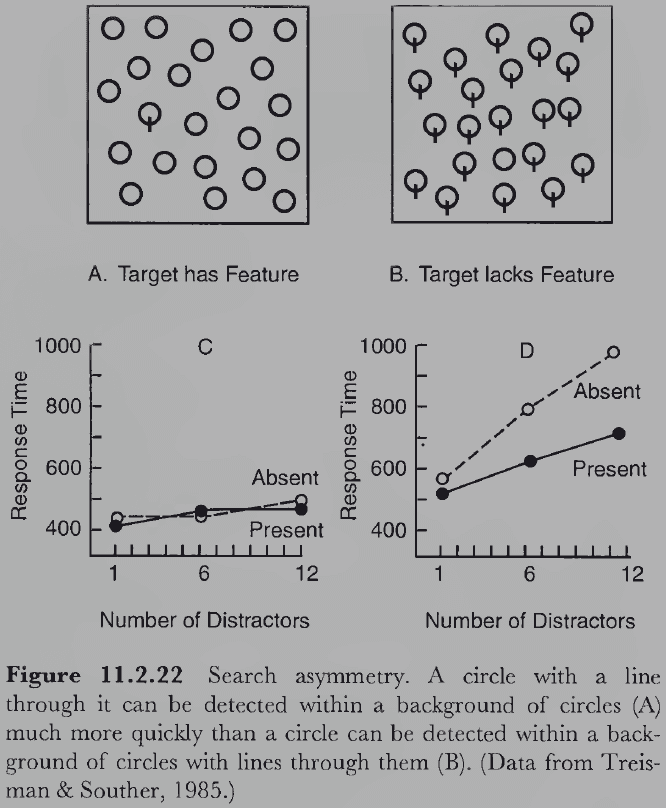

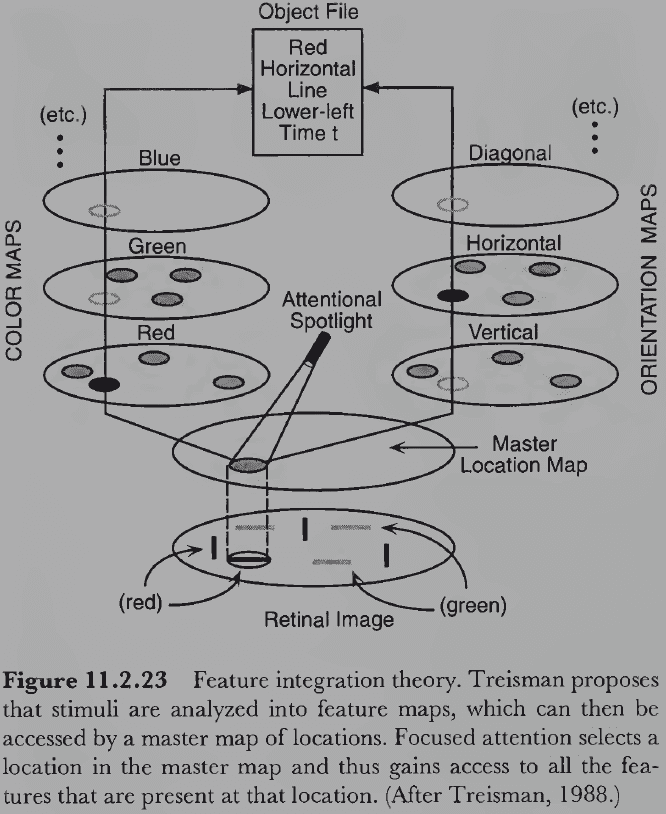

- In general, cortical cells tuned to high frequencies have a narrower/tighter tuning than cells tuned to low frequencies.