Psychology Applied To Modern Life

By Wayne Weiten, Dana Dunn, Elizabeth HammerMarch 17, 2021 ⋅ 74 min read ⋅ Textbooks

The unexamined life is not worth living.

Chapter 1: Adjusting to Modern Life

- We are the children of technology.

- Paradox of progress: despite our technological progress, social problems and personal difficulties seem more prevalent than ever before.

- E.g. Modern technology has provided us with countless time-saving devices but most of us complain about not having enough time.

- People find themselves tied to their jobs by the same tools that were supposed to liberate them.

- Another point is that even though modern society has an abundance of choice, more alternatives means increased regret and decision fatigue.

- Endless choices lead to wasted hours weighing trivial decisions and ruminating about whether the decision was optimal.

- The technological advances of the past century haven’t led to a perceptible improvement in our collective health and happiness.

- Possible reasons for this paradox

- Our value system may be scrambled due to the enormous weight we place on progress.

- Overwhelmed by rapidly accelerating cultural change.

- Mental demands of modern life have become so complex, confusing, and contradictory.

- Excessive materialism.

- Many theorists agree that the basic challenge of modern life has become the search for meaning, a sense of direction, and a personal philosophy.

- Many self-help gurus and self-realization programs aren’t helpful and are simply lucrative money-making schemes.

- However, the demand for such programs shows just how desperate some people are for a sense of direction and purpose in their lives.

- The multitude of self-help books that crowd bookstore shelves represent just one more symptom of our collective distress and our search for the elusive secret of happiness.

- Four shortcomings of self-help books

- Dominated by psychobabble.

- Places more emphasis on sales than on scientific soundness.

- Doesn’t provide explicit directions about how to change your behavior.

- Encourages a self-centered, narcissistic approach to life.

- Narcissism: a personality trait marked by an inflated sense of importance, a need for attention and admiration, a sense of entitlement, and a tendency to exploit others.

- This textbook is about the challenges of living in a complex, modern society.

- Psychology: the science that studies behavior and the mental processes that underlie it.

- Psychology lives two lives: one as a profession to help people and one as a science to better understand ourselves.

- Behavior: any overt/observable response or activity by an organism.

- Psychology doesn’t just focus on behavior as mental processes, while not directly observable, have influence over human behavior.

- Adjustment: the psychological processes through which people manage or cope with the demands and challenges of everyday life.

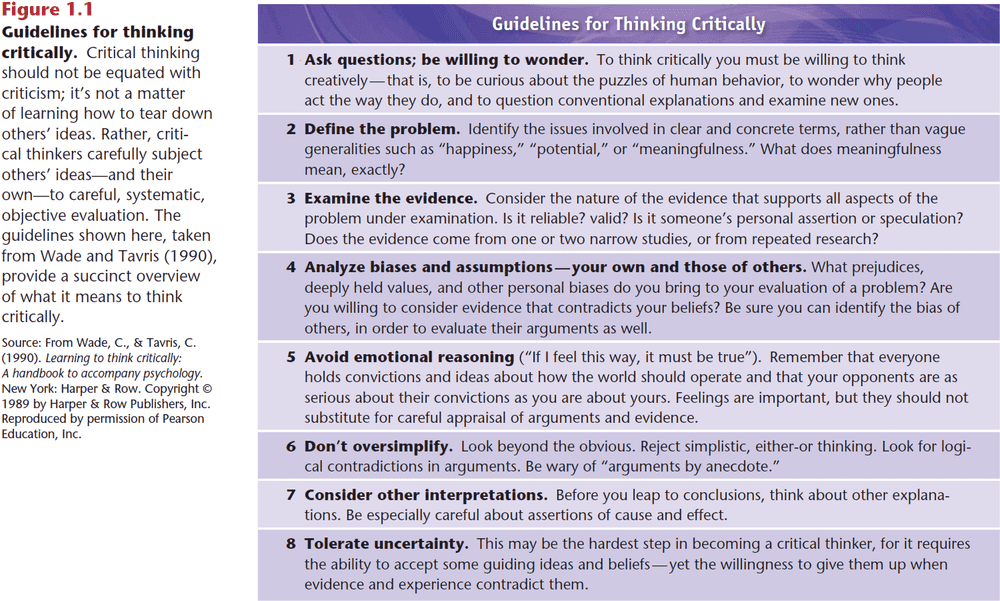

- Review of the scientific method, empiricism, experimental vs correlational studies, correlation coefficient.

- One interesting study compared the facial expressions of sighted and blind athletes to determine if emotions are learned or if they’re hardwired.

- If facial expressions are learned, then the blind athletes shouldn’t display any facial expressions since they can’t have seen them to learn them.

- Since the facial expressions were indistinguishable, the findings provide strong support for the hypothesis that facial expressions that go with emotions are hardwired into the human brain.

- Another interesting study on cross-cultural data showed that males reported a greater desire in the number of sex partners over the next 30 years compared to females in all ten world regions.

- While correlational research allows psychologists to explore a variety of phenomenon, it can’t demonstrate conclusively that two variables are causally related.

- Correlation doesn’t imply causation. We don’t know which variable causes which or whether both are caused by a third variable (confound).

- Subjective well-being: a person’s personal assessment of their overall happiness/life satisfaction.

- Many commonsense notions about happiness appear to be inaccurate.

- E.g. The widespread assumption that most people are relatively unhappy. Yet studies consistently find that most people are happy.

- Factors that aren’t very important for happiness

- Money

- There’s a weak positive correlation between money and feelings of happiness.

- Once people are above the poverty level, there’s little relation between income and happiness.

- There’s some evidence that people who place a strong emphasis on the pursuit of wealth and materialistic goals tend to be somewhat unhappier than others.

- Money aids happiness in that it reduces the negative impact of life’s setbacks.

- Age

- There’s no relationship between age and happiness.

- People’s average level of happiness tends to remain stable over their life span.

- Gender

- Parenthood

- Intelligence

- Physical attractiveness

- Money

- Factors that are somewhat important for happiness

- Health

- Social activity

- Religion

- Culture

- Factors that are very important for happiness

- Love, marriage, and relationship satisfaction

- Work

- Genetics and personality

- The best predictor of future happiness is that person’s past happiness.

- Insights on human happiness

- Objective realities aren’t as important as subjective feelings.

- When it comes to happiness, everything is relative.

- Research on happiness has shown that people are surprisingly bad at predicting what will make them happy.

- Research on subjective well-being indicates that people often adapt to their circumstances.

- Hedonic adaptation: when the mental scale that people use to judge their experiences shifts so that their neutral point/baseline is changed.

- Three ways to improve academic performance

- Set up a schedule for studying

- Find a place to study where you can concentrate

- Reward your studying

- Review of study methods (distributed retrieval, mnemonic devices).

Chapter 2: Theories of Personality

- Personality differences significantly influence people’s patterns of adjustment.

- E.g. If three people are stuck in an elevator, one person may crack jokes to relieve the tension, another person might be pessimistic about getting out, while the third may try to find a way out.

- Personality: an individual’s unique collection of consistent behavioral traits.

- Personality trait: a durable disposition to behave in a certain way in a variety of situations.

- E.g. Honest, impulsive, suspicious, anxious, and friendly.

- Most trait theories of personality assume that some traits are more basic than others.

- So a small number of fundamental traits determines other, more superficial traits.

- Five-factor model of personality (Big Five)

- Extraversion: outgoing, sociable, upbeat, friendly, assertive, and gregarious.

- Neuroticism: anxious, hostile, self-conscious, insecure, and vulnerable.

- Openness to experience: curiosity, flexibility, vivid fantasy, and imaginative.

- Agreeableness: sympathetic, trusting, cooperative, modest, and straightforward.

- Conscientiousness: diligent, disciplined, well organized, punctual, and dependable.

- The Big Five model has become the dominant personality theory in contemporary psychology as it’s been supported by many studies.

- However, are five traits enough to capture the variability seen in human personality?

- Freud’s Psychoanalytic Theory

- Psychoanalysis: a procedure to treat mental disorders that involved lengthy verbal interactions with patients’ lives.

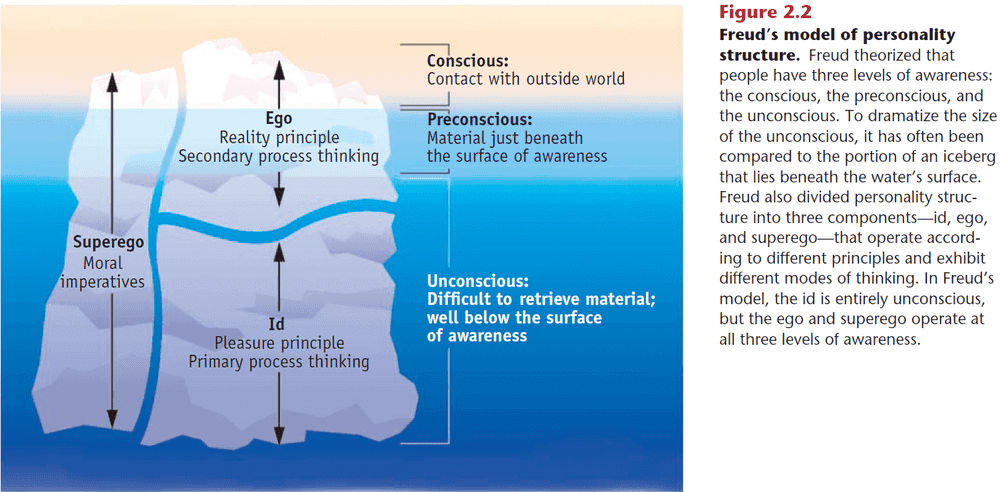

- Three parts of personality

- Id: primitive, instinctive component of personality that is based on the pleasure principle.

- Ego: decision-making component of personality that is based on the reality principle.

- Superego: moral component of personality that is based on social standards about what represents right and wrong.

- Three levels of awareness

- Conscious: whatever one is aware of at a particular point in time.

- Preconscious: material just beneath the surface of awareness that can be easily retrieved.

- Unconscious: thoughts, memories, and desires that are well below the surface of conscious awareness but that influence your behavior.

- Freud argued that behavior is the outcome of an ongoing internal conflict between the id, ego, and superego.

- Defense mechanism: unconscious reactions that protect a person from painful emotions.

- Rationalization: creating false but plausible excuses to justify unacceptable behavior.

- Repression: keeping distressing thoughts and feelings buried in the unconscious.

- Projection: attributing one’s own thoughts, feelings, or motives to another.

- Displacements: diverting emotional feelings (usually anger) from their original source to a substitute target.

- Reaction formation: behaving in a way that’s exactly the opposite of one’s true feelings.

- Regression: reverting to immature patterns of behavior.

- Identification: bolstering self-esteem by forming an imaginary/real alliance with some person or group.

- Sublimation: when unconscious, unacceptable impulses are channeled into socially acceptable behaviors.

- Skipping over Freud’s stages of psychosexual development.

- Skipping over Jung’s Analytical Psychology and Adler’s Individual Psychology.

- While it’s easy to ridicule and criticize these psychodynamic theories, we have to remember that they’re over a century old and we have to be impressed by their extraordinary impact on modern thought.

- No other theoretical perspective in psychology has been as influential, except for behaviorism.

- Behaviorism: a theoretical orientation based on the premise that scientific psychology should study observable behavior and ignore internal phenomenon (mind and mental processes).

- The argument for behaviorism is that since we can’t study mental processes in a scientific manner (since they’re private and not accessible to outside observation), we should only focus on what we can observe: behavior.

- Behaviorism is no longer dominant in psychology but it has been extremely influential.

- Most behaviorists view personality as a collection of response tendencies that are tied to various stimulus situations, and they explain everything through the lens of learning.

- Classical conditioning: a type of learning where a neutral stimulus acquires the capacity to evoke a response that was originally evoked by another stimulus.

- Review of Pavlov’s dog experiment with the bell and salivation.

- Pavlov demonstrated how learned reflexes are acquired (conditioned reflex).

- In everyday life, it contributes to our learned emotional responses such as anxieties, fears, and phobias.

- Extinction: the gradual weakening and disappearance of a conditioned response tendency.

- Classical conditioning explains reflexive responses that are controlled by stimuli that precede a response.

- However, both animals and humans make many responses that don’t fit this description.

- E.g. Studying. The stimuli that controls studying, say grades and exams, doesn’t precede it.

- Operant conditioning: a type of learning where voluntary responses are controlled by their consequences.

- Operant conditioning probably governs a larger share of human behavior than classical conditioning, since most human responses are voluntary rather than reflexive.

- Since they’re voluntary, operant responses are said to be emitted rather than elicited.

- B. F. Skinner studied and discovered operant conditioning.

- The fundamental principle behind operant conditioning is that organisms tend to repeat the responses that are followed by favorable consequences, rather than neutral/unfavorable consequences.

- Three types of operant conditioning

- Reinforcement

- Positive: when a response is strengthened because it’s followed by a pleasant stimulus.

- Negative: when a response is strengthened because it’s followed by an unpleasant stimulus.

- Like in classical conditioning, the effects of operant conditioning may not last forever (extinction).

- Punishment: when a response is weakened because it’s followed by an unpleasant stimulus.

- Reinforcement

- Bandura’s Social Cognitive Theory

- Bandura added a cognitive flavor to behaviorism.

- Observational learning: when an organism’s response is influenced by the observation of others.

- Observational learning is an indirect type of learning.

- People are more likely to copy a behavior if it leads to positive outcomes and the person they’re copying is similar to themselves.

- Self-efficacy: a person’s belief about their ability to perform behaviors that should lead to expected outcomes (or in other words confidence).

- Greater self-efficacy is associated with positive outcomes in life.

- Criticisms of behaviorism

- Neglect of cognitive processes

- Overdependence on animal research

- No unifying approach to personality

- Humanistic theory emerged as somewhat of a backlash against behaviorism and psychodynamic theories.

- Humanism: a theoretical orientation that emphasizes the unique qualities of humans, such as free will and their potential for personal growth.

- Humanistic principles

- Human nature includes an innate drive toward personal growth.

- Individuals have the freedom to chart their courses of action and aren’t pawns of their environment.

- Humans are largely conscious and rational beings who aren’t dominated by unconscious, irrational needs and conflicts.

- Roger’s Person-Centered Theory

- Self-concept: a collection of beliefs about one’s own nature, unique qualities, and typical behavior.

- Incongruence: the disparity between one’s self-concept and one’s actual experience.

- In other words, incongruence is the difference between your perceived self and your actual self.

- People often go to great lengths to defend their self-concept.

- Maslow’s Theory of Self-Actualization

- Review of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

- You have to satisfy needs at the previous level to activate the needs of the next level.

- Criticisms of humanism

- Poor testability

- Unrealistic view of human nature

- Inadequate evidence

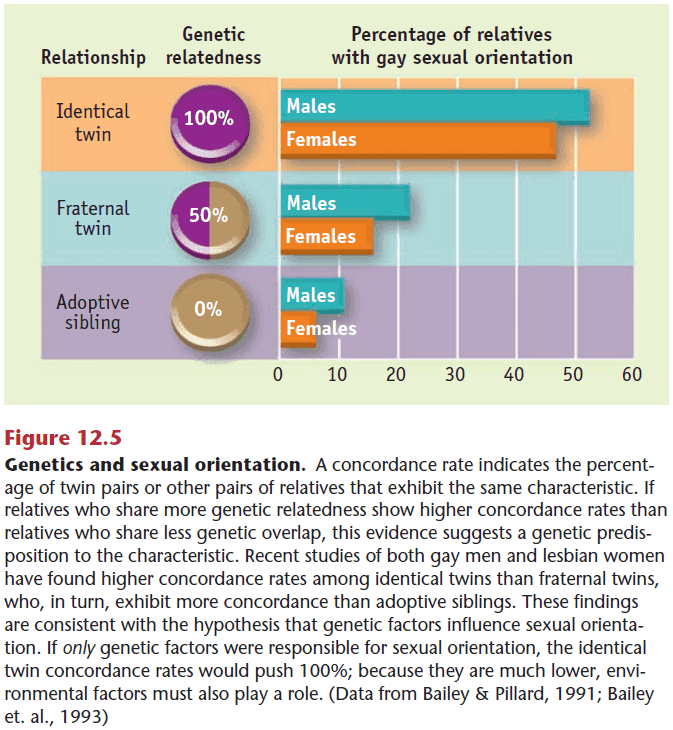

- Could personality be largely inherited?

- Heritability ratio: a trait’s probability of being heritable.

- E.g. 90% of height and 50-70% of intelligence.

- Evidence from twin studies suggest that heredity exerts considerable influence over many personality traits.

- E.g. Identical twins are more similar than fraternal twins on the Big Five personality test.

- However, one confounding variable is that twins are usually raised in the same environment so to adjust for this, we can study twins that were raised apart.

- Identical twins raised apart had a more similar personality than fraternal twins raised together.

- Based on the Minnesota study, around 50% of personality is heritable.

- Evolutionary psychology: examining behavioral processes in terms of their adaptive value for survival and reproduction.

- The idea is that natural selection favors behaviors that enhance organisms’ reproductive success.

- Criticisms of the biological perspective

- Problems with estimates of hereditary influences

- Hindsight bias in evolutionary theory

- Lack of adequate theory

- Skimming over sensation seeking, terror management theory, standardization, test norms, reliability, and validity.

Chapter 3: Stress and Its Effects

- How do people adjust to stress and how might they adjust more effectively?

- Stress: any circumstances that threaten or are perceived to threaten one’s well-being and thereby tax one’s coping abilities.

- Stress is a complex concept.

- Many studies have found that minor stressors can have a larger impact on mental health than major life events.

- It’s theorized that stressful events can be cumulative/additive in impact. In other words, stress can add up.

- Events that are stressful for one person may not be stressful to another.

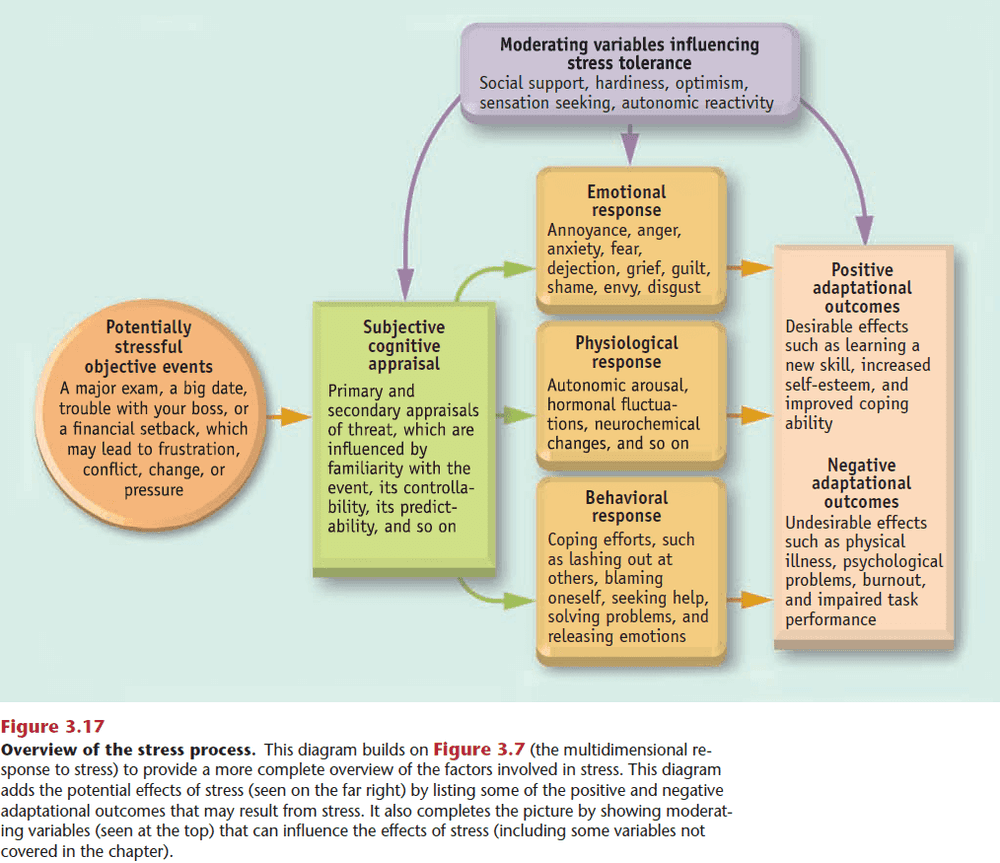

- Primary appraisal: an initial evaluation of whether an event is irrelevant, relevant, or stressful.

- Secondary appraisal: an evaluation of your coping resources and options for dealing with the stress.

- E.g. Can you handle riding the rollercoaster a second time?

- Some people are more prone to feel threatened by life’s difficulties than others.

- Cultures vary greatly in the dominant forms of stress their people experience.

- Culture sets the context in which people experience and appraise stress.

- Substantial evidence shows that cultural changes, such as increased modernization and urbanization, has been a major source of stress in many societies around the world.

- E.g. Racial discrimination and immigration.

- Acute stressors: threatening events that have a relatively short duration and a clear end.

- E.g. Final exam for a class or a video game.

- Chronic stressors: threatening events that have a relatively long duration and no apparent end.

- E.g. Financial strains, pressures from work, or demands from a sick family member.

- Anticipatory stressors: upcoming or future events that are perceived to be threatening.

- E.g. Potential break-up and natural disasters.

- Four major sources of stress

- Frustration: any situation where the pursuit of a goal is thwarted. Whenever you want something but you can’t have it.

- E.g. Traffic jams, long commutes, putting in work but not seeing results.

- Frustration often leads to aggression or burnout.

- Internal conflict: when two or more incompatible motivations or behavioral impulses compete for expression.

- Three types: approach-approach (two good choices), avoidance-avoidance (two bad choices), and approach-avoidance (a choice with both good and bad).

- Approach-avoidance conflicts are common and are more stressful than the other two conflicts.

- E.g. Deciding between two items on a menu, deciding to ask out an attractive person.

- Life changes: any noticeable alterations in one’s living circumstances that require readjustment.

- Disruptions of daily routines are stressful.

- More research is needed to determine whether life changes are inherently stressful.

- E.g. Death of spouse, moving cities, vacation.

- Pressure: expectations/demands that one behave in a certain way.

- Two subtypes: the pressure to perform and the pressure to conform.

- E.g. Work pressure, academic pressure, self-imposed pressure.

- Frustration: any situation where the pursuit of a goal is thwarted. Whenever you want something but you can’t have it.

- Different levels stress impacts

- Emotional: powerful, largely uncontrollable feelings.

- Contrary to common sense, positive emotions don’t vanish during times of severe stress and appear to help people overcome the negative emotions associated with stress.

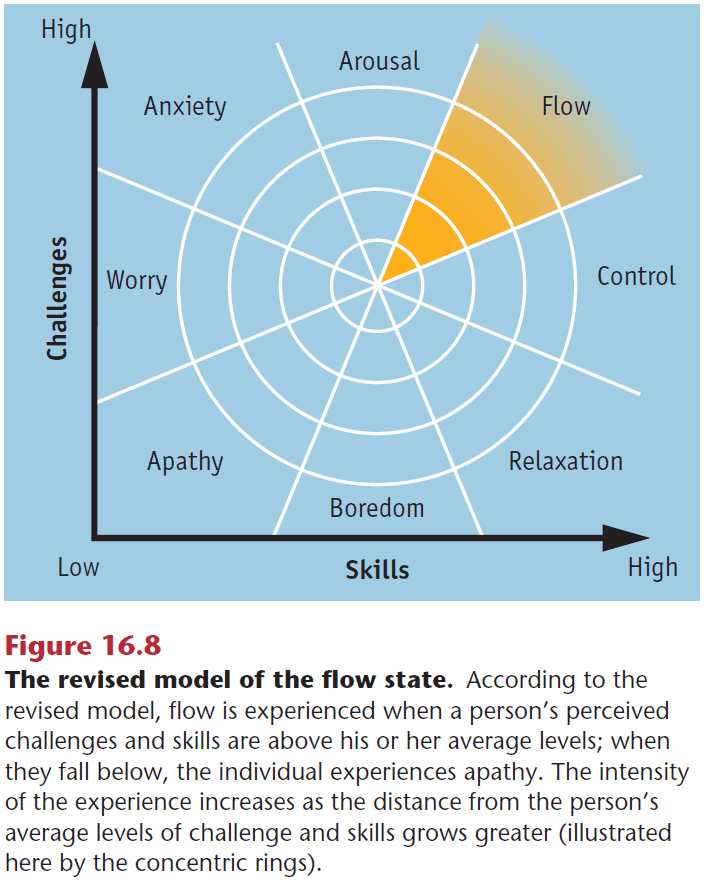

- Inverted-U hypothesis: as arousal increases, so does performance (up to a point).

- The optimal level of arousal for a task appears to depend on the complexity of the task.

- As tasks become more complex, the optimal level of arousal tends to decrease.

- Physiological

- Fight-or-flight response: a physiological reaction to threat where an organism decides to either attack (fight) or flee (flight) an enemy.

- This response is controlled by the body’s sympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system.

- While this response was probably useful in ancestral humans, modern humans deal with more complex problems that can’t be solved by either fighting or fleeing.

- Exposing lab animals to various stressors results in similar patterns of physiological arousal, regardless of the type of stress.

- General adaptation syndrome: a three-stage model of the body’s stress response (alarm, resistance, and exhaustion).

- The body recognizes the existence of a threat and sets off an alarm reaction.

- The body adapts to the new conditions of stress through homeostasis.

- The body becomes exhausted fighting the stress and resistance declines.

- It’s becoming clear that stress affects every part of the body through hormones.

- Behavioral

- Unlike the previous two responses, behavioral responses aren’t automatic and are under our control.

- Most behavioral responses to stress involve coping.

- Coping: efforts to master, reduce, or tolerate the demands created by stress.

- Coping responses can be either healthy or unhealthy.

- Emotional: powerful, largely uncontrollable feelings.

- Potential effects of stress

- Impaired task performance

- Choking under pressure is fairly common in normal people but surprisingly less common in experts and professional athletes.

- Disruption of cognitive functioning

- Stress disrupts two aspects of attention.

- It increases people’s tendency to jump to conclusions.

- It increases people’s tendency to do an unsystematic review of their options.

- Stress disrupts two aspects of attention.

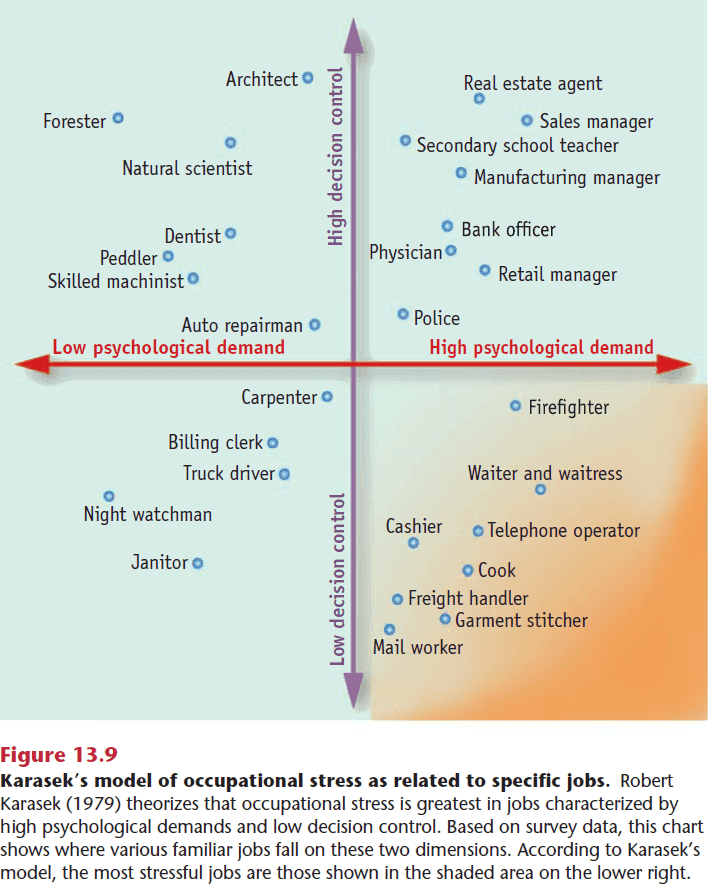

- Burnout: a syndrome involving physical and emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and a lowered sense of self-efficacy that’s attributable to work-related stress.

- Exhaustion is central to the idea of burnout.

- Burnout is a cumulative stress reaction to ongoing occupational stressors.

- Psychological problems and disorders

- Extremely stressful and traumatic events can leave a lasting imprint on victims’ psychological functioning.

- E.g. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from war, rape, serious car accidents, death, natural disasters.

- Common symptoms include nightmares, emotional numbing, alienation, and elevated arousal, anxiety, and guilt.

- The frequency and severity of posttraumatic symptoms usually decline gradually over time, but in many cases the symptoms never completely disappear.

- One key predictor of whether a person will develop PTSD is the intensity of their reaction at the time of the traumatic event.

- Vulnerability seems to be greatest among people whose reactions are so intense that they report dissociative experiences.

- Dissociative experience: a sense that things aren’t real, that time is stretching out, or that one is watching oneself in a movie.

- Physical illness

- Psychosomatic diseases: genuine physical ailments thought to be caused by stress and other psychological factors.

- E.g. High blood pressure, peptic ulcers, asthma, headaches, and skin disorders.

- The concept of psychosomatic disease has gradually fallen out of use because research has shown that stress can contribute to the development of an array of other diseases.

- Thus, there’s nothing unique about psychosomatic diseases that requires a special category.

- Positive effects

- The effects of stress aren’t entirely negative.

- Some psychologists have argued that psychology has focused too much on the negative aspects of the mind and how to heal suffering, neglecting the forces that make life worth living.

- This movement has been called “positive psychology” and it seeks to shift the field’s focus away from negative experiences to more positive experiences.

- Three ways stress can have positive effects

- Stress can promote positive psychological change.

- Stressful events help satisfy the need for stimulation and challenge, a basic need of the human organism.

- Stress can help prepare people to be less affected by future stress; improving stress tolerance.

- Impaired task performance

- Why do some people handle stress better than others?

- It’s due to a number of moderator variables such as

- Social support: aid provided by social networks.

- Social support could promote wellbeing by dampening the intensity of physiological reactions to stress, reducing health-impairing behaviors, and fostering more constructive coping efforts.

- Studies also show that providing social support can also have benefits but there are potential drawbacks such as conflict, additional responsibilities, and dependency.

- Hardiness: a disposition marked by commitment, challenge, and control that may be associated with strong stress resistance.

- Optimism: a general tendency to expect good outcomes.

- Over 20 years of research has consistently shown that optimism is associated with better mental and physical health.

- Social support: aid provided by social networks.

- Behavior modification: a systematic approach to changing behavior through the application of the principles of conditioning.

- This assumes that behavior is a product of learning, conditioning, and environmental control, and that what was learned can be unlearned.

- Five steps in the process of self-modification

- Specifying your target behavior

- Many people have difficulty specifying the exact behavior that they wish to change.

- E.g. People tend to describe their problems in terms of unobservable personality traits rather than behaviors such as wishing to change that “I’m too irritable.”

- You need to list specific examples of responses that lead to a trait that you wish to change.

- Gather baseline data

- Systematically observe your target behavior for a period of time.

- Three things to monitor

- Identify possible controlling antecedents

- Determine initial level of response

- Identify possible controlling consequences

- You can’t tell whether your program is working effectively unless you have a baseline to compare it to.

- It’s crucial to gather accurate data.

- Design your program

- Generally, your program will either increase or decrease the frequency of a target response.

- This can be done using positive/negative reinforcement, punishment, and control of antecedents/triggers.

- Execute and evaluate your program

- Once the program has been designed, you have to put in the work to follow through with it.

- During this phase, you need to continue to accurately record the frequency of your target behavior so you can evaluate your progress.

- The most common form of cheating is to reward yourself when it wasn’t earned.

- Bring your program to an end

- This involves setting terminal goals and gradually phasing out your program.

- If your program is successful, it may fade away without a conscious decision.

- Often, new and improved behaviors become self-maintaining.

- Specifying your target behavior

Chapter 4: Coping Processes

- Decisions on how to cope with life’s difficulties can be incredibly complex.

- This chapter focuses on how people cope with stress.

- Coping: efforts to master, reduce, or tolerate the demands created by stress.

- General points about coping

- People cope with stress in many ways.

- E.g. One literature review found over 400 distinct coping techniques.

- It’s most adaptive to use a variety of coping strategies.

- Coping strategies vary in their adaptive value.

- People cope with stress in many ways.

- No coping strategy can guarantee a successful outcome as the adaptive value of a coping technique depends on the exact nature of the situation.

- Common non-optimal coping mechanisms

- Giving up

- Learned helplessness: a passive behavior produced by exposure to unavoidable aversive events.

- E.g. When lab animals were given electric shocks that they couldn’t escape from, they were given two choices. One choice was an opportunity to learn a response that would allow them to escape the shock, the other choice was to give up. Many of the animals chose to give up. Human subjects show parallel results.

- Unfortunately, this tendency to give up may be transferred to situations where one isn’t really helpless.

- Some people routinely respond to stress with fatalism and resignation.

- Helplessness seems to occur when people come to believe that events are beyond their control.

- However, giving up can be adaptive in some situations where you’re genuinely helpless.

- Withdrawing effort from unattainable goals can be an effective coping strategy.

- Aggression

- Aggression: any behavior intended to hurt someone, either physically or verbally.

- Lashing out at others with verbal aggression tends to be ineffective and often backfires, creating additional stress.

- Frustration does frequently elicit aggression.

- Catharsis: the release of emotional tension.

- It’s common to believe that “blowing off steam” is good advice but evidence shows otherwise.

- Experimental research has generally not supported catharsis and most studies find the opposite: behaving in an aggressive manner tends to fuel more anger and aggression.

- Exposure to media violence not only desensitizes people to violent acts, but it also encourages aggressive self-views and automatic aggressive responses.

- Evidence suggests that video games and violent media don’t provide a cathartic effect, but rather increase aggressive tendencies.

- As a coping strategy, acting aggressively has little value.

- Self-indulgence

- A common response to stress is to reward yourself in another area of your life.

- E.g. Eating something sweet, going on a spending spree, or drinking, gambling, and using drugs.

- There’s nothing inherently bad about indulging oneself as a way to cope with stress.

- However, excessive self-indulgence is when problems start to develop.

- E.g. Stress-induced eating is usually unhealthy and may result in poor nutrition or obesity.

- Self-blame

- When confronted by stress, people often become highly self-critical.

- E.g. The coach blaming themselves for the team’s loss.

- Self-blame tendencies

- Unreasonably attributing their failures to personal shortcomings.

- Focusing on negative feedback from others while ignoring positive feedback.

- Making unduly pessimistic projections about the future.

- Self-blame as a coping strategy can be very counterproductive.

- Defense mechanisms

- Defense mechanisms: unconscious reactions that protect a person from unpleasant emotions such as anxiety and guilt.

- They shield a person from the emotional discomfort elicited by stress and is also used to prevent dangerous feelings from exploding into acts of aggression.

- Defense mechanisms work through self-deception by bending reality in self-serving ways.

- Most people use defense mechanisms on a fairly regular basis.

- Generally, defense mechanisms are poor ways of coping because it avoids the situation, represents wishful thinking, and it delays a person from facing the problem.

- Although illusions may protect us in the short term, they can create serious problems in the long term.

- Giving up

- Constructive coping: efforts to deal with stressful events that are judged to be relatively healthy.

- Key themes of constructive coping

- Confront problems directly.

- Takes effort.

- Based on realistic judgements of your stress and coping resources.

- Involves learning to recognize and manage potentially disruptive emotional reactions.

- Involves learning to exert some control over potentially harmful/destructive behaviors.

- Three classes of constructive coping

- Appraisal-focused: aimed at changing one’s interpretation of stressful events.

- Problem-focused: aimed at altering the stressful situation itself.

- Emotion-focused: aimed at managing potential emotional distress.

- Appraisal-focused

- People often underestimate the importance of this phase in dealing with stress.

- A useful way of dealing with stress is to change your judgement/appraisal of the events.

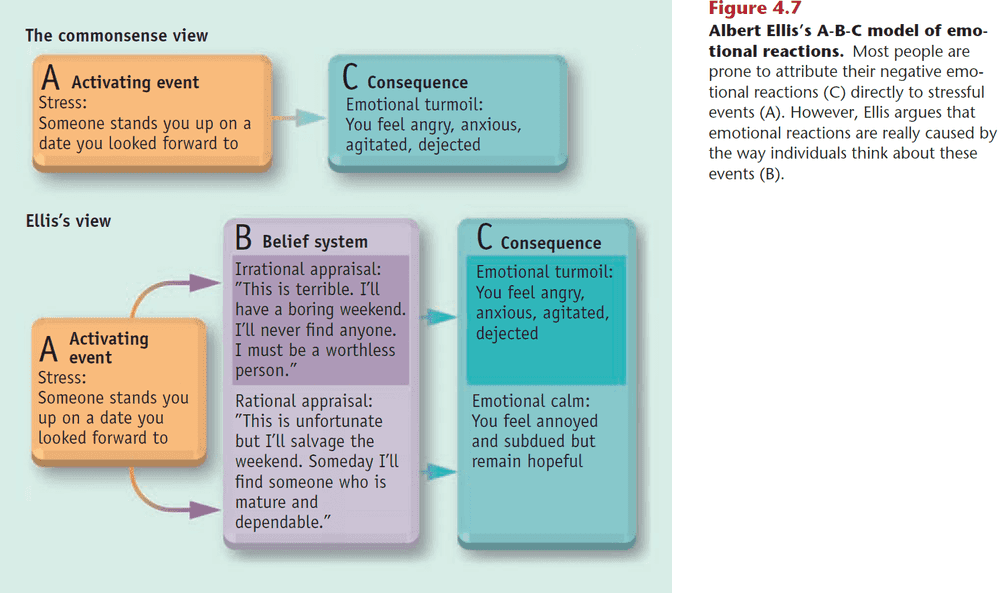

- The core idea to this approach is that you feel the way you think.

- Emotional reactions are caused by the ways people think about stressful events, and not caused by the event itself.

- Most people don’t understand the importance of the B or belief phase.

- Catastrophic thinking: unrealistic appraisals of stress that exaggerate the magnitude of the problem.

- One way to avoid catastrophic thinking is to question your assumptions and to replace it with a more rational analysis.

- Another way people deal with stress is through humor.

- Studies found that high humor is related to lower stress and vice versa.

- Positive reinterpretation or thinking that “things could be worse” is another useful coping strategy that can decrease stress.

- Instead of comparing to a worse situation, you can also find the positive aspects of the stressful event.

- Problem-focused

- In dealing with problems, the most obvious course of action is to tackle them head-on.

- Problem solving has been linked to better psychological adjustment, lower levels of depression, and fewer health complaints.

- Systematic problem solving steps

- Clarify the problem

- Generate alternative courses of action

- Evaluate the alternatives and select a course of action

- Take action while maintaining flexibility

- Other coping strategies include seeking help from others and using time more effectively.

- Time is a non-renewable resource.

- People vary in their time perspective. Some people are future-oriented and see the consequences of immediate behavior, whereas others are present-oriented and focus on immediate events and don’t worry about consequences.

- These orientations influence how they manage their time, as future-oriented people are less likely to procrastinate and are more reliable in meeting their commitments.

- The key to better time management is increased effectiveness or learning to allocate time to your most important tasks.

- “Efficiency is doing the job right, while effectiveness is doing the right job.”

- Steps for better time management

- Monitor your use of time

- Clarify your goals

- Plan your activities using a schedule

- Protect your prime time

- Increase your efficiency

- Even though planning takes time, it saves time in the long run.

- Emotion-focused

- Emotional intelligence (EI): the ability to perceive and express emotion, use emotions to facilitate thought, understand and reason with emotion, and regulate emotion.

- Four key components of EI

- Accurately perceive emotions in themselves and in others.

- Be aware of how emotions shape their thinking.

- Understand and analyze their emotions, which may be complex and contradictory.

- Regulate their emotions to dampen negative emotions and to use positive emotions.

- Emotional expression through talking and writing about traumatic events can be beneficial.

- Emotional disclosure or “opening up” is also associated with improved mood and more positive self perceptions.

- Writing about emotional experiences can be a helpful coping strategy.

- Forgiveness: counteracting the natural tendencies to seek vengeance or avoid an offender, thereby releasing this person from further liability for their transgression.

- Another healthy way to deal with overwhelming emotions is to engage in physical exercise.

- It’s well documented that physical activity promotes overall mental and physical health.

- Meditation has also seen an increased interested as a way to deal with negative emotions.

- Meditation: a family of mental exercises where a conscious attempt is made to focus attention in a nonanalytical way.

- Life is a journey and death is the ultimate destination.

- Educating yourself about death and dying can help you cope with the grieving process.

- The most common strategy for coping with death is avoidance.

- Death anxiety: fear and apprehension about one’s own death.

- Five stages of confronting death (grief)

- Denial

- Anger

- Bargaining

- Depression

- Acceptance

- Bereavement: the painful loss of a loved one through death.

- Less anxiety about death is found among those who have a well-formulated philosophy of death.

Chapter 5: Psychology and Physical Health

- The past few decades of research have shown that health is affected by social, psychological, and biological factors.

- This chapter focuses on the fact that more than at any other time in history, people’s health is more likely to be compromised by chronic diseases, rather than contagious diseases.

- Lifestyle and stress play a much larger role in the development of chronic diseases than they do in contagious diseases.

- Today, the three leading chronic diseases (heart disease, cancer, and stroke) account for almost 60% of all deaths in the USA.

- Biopsychosocial model: that physical illness is caused by a complex interaction of biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors.

- Health psychology: how psychosocial factors relate to the promotion and maintenance of health and with the causation, prevention, and treatment of illness.

- Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the USA, accounting for nearly 27% of deaths.

- Coronary heart disease: a reduction in blood flow through the arteries that supply the heart with blood.

- Two personality types

- Type A: strong competitive orientation, impatient and time urgent, and anger and hostility.

- Type B: relatively relaxed, patient, easygoing, and amicable behavior.

- Research has uncovered a modest correlation between Type A behavior and increased coronary risk.

- Hostility: a persistent negative attitude marked by cynical, mistrusting thoughts, feelings of anger, and overtly aggressive actions.

- Recent research suggests that hostility may be the crucial toxic element that accounts for the correlation between Type A behavior and heart disease.

- Possible explanations linking anger and hostility

- Anger-prone individuals appear to exhibit greater physiological reactivity than those lower in hostility.

- Hostile people probably create additional stress for themselves.

- Hostile individuals tend to have less social support than others.

- People high in anger and hostility seem to exhibit a higher prevalence of poor health habits.

- Depression roughly doubles the chances of developing heart disease.

- Cancer: malignant cell growth that occurs in the body.

- Stress is related to (but isn’t necessarily causally linked to) cancer.

- The apparent link between stress and many types of illness probably reflects the fact that stress can undermine the body’s immune functioning.

- The duration of a stressful event is a key factor determining its impact on immune function.

- Stress can temporarily suppress human immune functioning, which can make people more vulnerable to infectious disease agents.

- Health-impairing habits contribute to far more deaths than most people realize.

- It may seem puzzling that people behave in self-destructive ways. Why?

- There are several factors

- Many health-impairing habits slowly creep up on people.

- E.g. Drug use or exercising less.

- Many health-impairing habits involve activities that are quite pleasant.

- E.g. Smoking and eating fatty foods.

- It’s relatively easy to ignore risks that lie in the distant future.

- E.g. Chronic diseases such as cancer take time to develop.

- People have a tendency to underestimate the risks associated with their own health-impairing habits.

- Many health-impairing habits slowly creep up on people.

- Skipping over the section on how health is affected by smoking, drinking, overeating, exercise, and reactions to illness and drug effects.

Chapter 6: The Self

- This chapter focuses on the self and its important role in adjustment.

- If you were asked to describe yourself, what would you say?

- You’d probably start off with some physical attributes and move on to psychological characteristics.

- E.g. I’m tall, average weight, blonde, friendly, honest, and intelligent.

- People probably define themselves by highlighting how they’re different from others.

- Self-concept: an organized collection of beliefs about the self.

- These beliefs are developed from past experience and are concerned with one’s personality traits, abilities, physical features, values, goals, and social roles.

- Possible selves: one’s conceptions about the kind of person one might become in the future.

- People’s beliefs about themselves aren’t set in stone, but they’re not easily changed either.

- Once the self-concept is established, the individual has a tendency to preserve and defend it.

- Some people perceive themselves pretty much the way they’d like to see themselves.

- Three types of self

- Actual: qualities actually possessed.

- Ideal: qualities would like to possess.

- Ought: qualities should possess.

- Self-discrepancy: a mismatch between the self-perceptions that make up the actual self, the ideal self, and the ought self.

- People with low self-discrepancy experience high self-esteem, while the opposite is true.

- Everyone experiences self-discrepancies, but most people manage to feel good about themselves.

- This is due to the amount of discrepancy you experience, your awareness of the discrepancy, and whether the discrepancy is actually important to you.

- One way to cope with self-discrepancies is to change your behavior to bring it more in line with your ideal and ought selves.

- Another way is to bring your ideal self more in line with your actual self.

- Another, less positive, approach is to blunt your self-awareness so that you focus less on judging yourself.

- E.g. If your weight is bothering you, you might stay off the scale or avoid looking into a mirror.

- Factors that influence self-concept

- Self-observations

- People begin observing and judging their own behavior early in life.

- Social comparison theory: individuals compare themselves with others to assess their abilities and opinions.

- Social comparison is used to accurately assess one’s abilities, but also to improve their skills and to maintain their self-image.

- E.g. Comparing your current self to your past self.

- Reference group: a set of people who are used as a gauge in making social comparisons.

- Upward social comparisons can motivate you to change, while downward social comparisons can boost self-esteem.

- People’s observations of their own behavior aren’t entirely objective and tend to be in a positive direction.

- E.g. 100% of respondents saw themselves as above average, while 25% of them thought that they belonged in the top 1%.

- This better-than-average effect seems to be a common phenomenon.

- Feedback from others

- Early in life, feedback from parents is especially tied to a child’s self-concept.

- Later in life, feedback from close friends and marriage partners takes importance.

- Individuals don’t see themselves exactly as others see them but rather as they believe others see them.

- Thus, feedback from others usually reinforces people’s self-views.

- Cultural values

- The society that one grows up in defines what’s desirable and undesirable in personality and behavior.

- One important way cultures differ is on the dimension of individualism versus collectivism.

- Self-observations

- Self-esteem: one’s overall assessment of one’s worth as a person.

- People with high self-esteem are confident, take credit for their actions, and are relatively sure of who they are.

- People with low self-esteem aren’t more negative, but rather they’re more confused and tentative.

- People with low self-esteem simply don’t know themselves well enough to strongly endorse many personal attributes on self-esteem tests, which results in lower self-esteem scores.

- Self-esteem can be interpreted in two ways

- Trait: the ongoing sense of confidence in your abilities and characteristics.

- State: how individuals feel about themselves in the moment.

- Investigating self-esteem is challenging because it’s difficult to measure, relies on self-report, and it’s difficult to separate cause from effect.

- Advantages of having a high self-esteem

- More positive emotions such as happiness

- More likely to speak up and criticize the group’s approach

- Persists longer in the face of failure

- Affects expectations in a reinforcing way

- Although high self-esteem is desirable, problems arise when people’s self-views are inflated and unrealistic as they’re often labeled as narcissistic.

- Aggression in response to self-esteem threats is more likely to occur in people who are narcissistic.

- Parents, teachers, coaches, and other adults play a key role in shaping self-esteem.

- Four parenting styles

- Authoritative: high acceptance, high control.

- Authoritarian: low acceptance, high control.

- Permissive: high acceptance, low control.

- Neglectful: low acceptance, low control.

- Authoritative and permissive parenting styles lead to the highest self-esteem for the child.

- Review of the cocktail party effect.

- Self-attributions: inferences that people draw about the causes of their own behavior.

- People routinely make attributions to make sense out of their experiences.

- Attributions are made along six dimensions

- Internal: personal factors.

- E.g. Saying that your failure to adequately prepare for the test or getting anxious as the cause for failing the test.

- External: environmental factors.

- E.g. Saying that the course or the teacher marked unfairly as the cause for failing the test.

- Stable

- Unstable

- Controllable

- Uncontrollable

- Internal: personal factors.

- Whether one’s self-attributions are internal or external can have tremendous impact on one’s personal adjustment.

- Explanatory style: the tendency to use similar causal attributions for a wide variety of events in one’s life.

- People with an optimistic explanatory style usually attribute setbacks to external, unstable, and specific factors, and this lets them bounce back from setbacks and helps to maintain a favorable self-image.

- In contrast, people with a pessimistic explanatory style usually attribute setbacks to internal, stable, and global factors.

- A pessimistic style can foster passive behavior and it makes people more vulnerable to learned helplessness and depression.

- Four major motives for seeking self-understanding

- Assessment: drive for truthful information about themselves.

- Verification: drive towards information that matches what they already believe about themselves.

- Improvement: drive to change themselves after failure.

- Enhancement: drive to maintain positive feelings about oneself.

- Downward social comparison: a defensive tendency to compare oneself with someone whose troubles are more serious than one’s own.

- Self-serving bias: the tendency to attribute one’s successes to personal factors and one’s failures to situational factors.

- Self-handicapping: the tendency to sabotage one’s performance to provide an excuse for possible failure.

- E.g. Not preparing for a test and then saying you did poorly because you didn’t prepare.

- Self-handicapping differs from defensive pessimism in that pessimists are motivated to avoid bad outcomes, whereas self-handicappers undermine their own effects (self-defeating behavior).

- While self-handicapping may save you from negative self-attributions about your ability, it doesn’t prevent others from making different negative attributions about you.

- Self-control: the process of directing and controlling one’s behavior.

- Self-control has been shown to be a resource that can be depleted when used.

- Self-efficacy isn’t concerned with the skills you have, but with your beliefs about what you can do with those skills.

- Four sources of self-efficacy

- Mastery experiences

- The most effective path to self-efficacy is through mastering new skills.

- Ironically, difficulties and failures can ultimately contribute to the development of a strong sense of self-efficacy.

- Vicarious experiences

- Another way to improve self-efficacy is by watching others perform a skill that you want to learn.

- Persuasion/encouragement

- Self-efficacy can also be developed through the encouragement of others.

- Interpretation of emotional arousal

- Mastery experiences

- People typically act in their own self-interest.

- E.g. Smoking, unprotected sex, procrastinating assignments.

- Self-defeating behavior: seemingly intentional actions that thwart a person’s self-interest.

- Three types of self-defeating behaviors

- Deliberate self-destruction: the desire to harm one’s self.

- Tradeoffs: accepting self harm to achieve a desirable goal.

- Counterproductive strategies: pursing a goal but using an approach that is bound to fail.

- There’s little evidence that people deliberately try to harm themselves and instead, self-defeating behaviors appear to be the result of people’s distorted judgements or strong desires to escape from immediate, painful feelings.

- Interestingly, people think others notice and evaluate them more than is the actual case.

- Impression management: conscious efforts made by people to influence how others think of them.

- Impression management strategies

- Ingratiation: behaving in ways to make oneself likeable to others.

- E.g. Giving compliments and doing favors for others.

- Self-promotion: playing up your strong points.

- E.g. I’m very good at math.

- Exemplification: demonstrating exemplary behavior to claim special credit.

- Negative acknowledgement: admitting to possessing some negative quality.

- Intimidation: threatening someone with a potential threat.

- Supplication: presenting one’s self as weak and dependent.

- Ingratiation: behaving in ways to make oneself likeable to others.

- Suggestions for building self-esteem

- Recognize that you control your self-image

- Learn more about yourself

- Don’t let others set your goals

- Recognize unrealistic goals

- Modify negative self-talk

- Emphasize your strengths

- Approach others with a positive outlook

Chapter 7: Social Thinking and Social Influence

- This chapter explores how people form impressions of others, as well as how and why such judgments can be incorrect.

- Social cognition: how people think about others and themselves.

- Person perception: the process of forming impressions of others.

- Since you can’t read people’s minds, you depend on observations of others to determine what they’re like.

- Five sources of observational information

- Appearance: how you look.

- Verbal behavior: what you say.

- Actions: what you do.

- Nonverbal messages: body language and facial expressions.

- Situational cues: setting where behavior occurs.

- Research indicates that one negative trait can have more influence on forming impressions than several positive traits.

- E.g. A single bad deed can eliminate a good reputation, but a good deed can’t redeem an otherwise bad reputation.

- Thus, in the realm of perceptions, bad impressions tend to be stronger than good ones.

- For impressions where accuracy isn’t a priority, snap judgments are often used to judge a person.

- However, when accuracy is a priority, people make systematic judgments rather than snap judgements.

- In systematic judgments, people are interested in learning why the person behaves in a certain way to predict their future behavior.

- Perceiver expectations: how your expectations of others can influence your perception of others.

- Two principles of perceiver expectations

- Confirmation bias: the tendency to seek information that supports one’s beliefs while not pursuing information that argues against those beliefs.

- Self-fulfilling prophecy: when expectations about a person cause them to behave in ways that confirm the expectations.

- People often take the easy path of categorizing others to avoid expending the cognitive effort that would be necessary for a more accurate impression.

- E.g. Us versus them.

- Stereotype: beliefs that people have certain characteristics because of their membership in a particular group.

- Attractive people are often attributed with unsupported positive characteristics due to their appearance.

- However, they’re not any different from others in intelligence, happiness, mental health, or self-esteem.

- Thus, attractive people are perceived in a more favorable light than is actually justified.

- Unfortunately, the positive biases toward attractive people also operate in reverse, with unattractive people being unjustifiable seen as less well adjusted than others.

- Research on attractiveness in relationships shows that the correlation between lovers’ respective levels of attractiveness is fairly robust.

- Because stereotyping is automatic, some psychologists are pessimistic about being able to control it, while others are more optimistic.

- One way to reduce prejudice is to exert some self-control over one’s view of others.

- One reason stereotypes persist is because they’re functional, meaning they help us trade accuracy for speed when thinking about others.

- Stereotypes also endure because of confirmation bias.

- Fundamental attribution error: the tendency to explain other people’s behavior as the result of personal, rather than situational, factors.

- A person’s behavior at any given time may or may not reflect their personality/character, but observers tend to assume that it does.

- A person’s behavior may be due to the situation/context that they’re in and not who they are.

- Again, the fundamental attribution error occurs because people are cognitively lazy.

- The first attribution step occurs spontaneously but the second step requires cognitive effort.

- So it’s easy to stop after the first step and thus make a snap judgement without taking situation and context into consideration.

- However, when people are motivated to form accurate impressions of others, they do expend the effort to complete the second step.

- Defensive attribution: a tendency to blame victims for their misfortune, so that one feels less likely to be victimized in a similar way.

- This attribution is a self-protective, but irrational, strategy for dealing with thoughts of catastrophes that could happen to oneself.

- Three themes in person perception

- Efficiency

- People prefer to not exert much effort/time in forming their impressions of others.

- A lot of social information is processed automatically and effortlessly.

- Advantages include quick and simple, disadvantages include inaccurate.

- Selectivity

- People see what they expect to see.

- Consistency

- Considerable research supports the idea that first impressions are powerful.

- Primacy effect: when the initial information carries more weight than subsequent information.

- Thus, getting off on the wrong foot may be particularly damaging.

- Why are primacy effects so potent? Because people find comfort in cognitive consistency.

- Efficiency

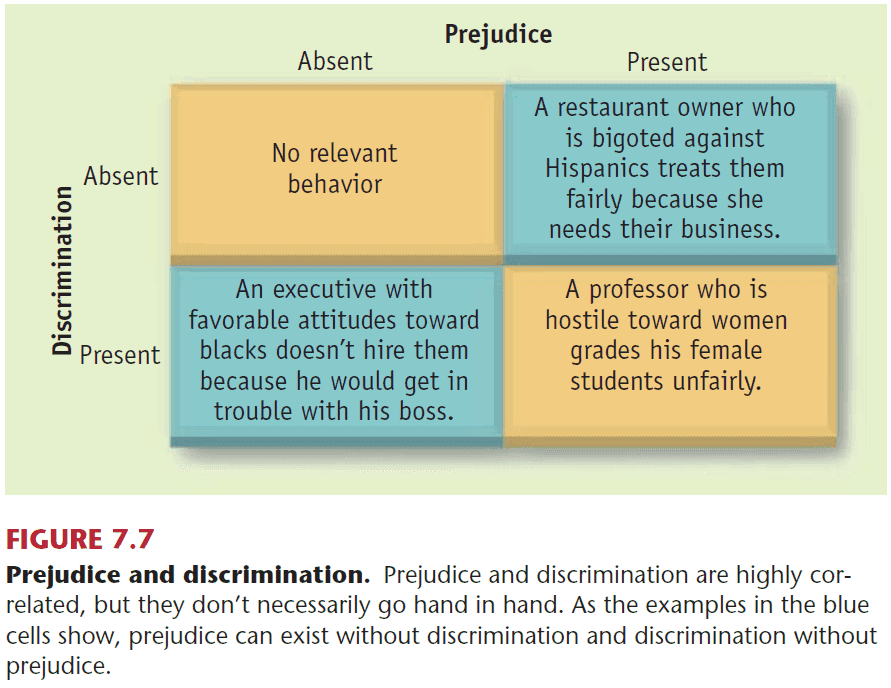

- Prejudice: a negative attitude toward members of a group.

- Discrimination: behaving differently, usually unfairly, towards the members of a group.

- While these two terms tend to go together, there are cases when they’re separate.

- E.g. Restaurants can still serve Chinese couples but have a prejudice against them. Likewise, a manager can favor black people but not hire them because his boss would be upset.

- Causes of prejudice

- Authoritarianism

- People who are right-wing authoritative score low on openness to experience and conscientiousness and tend to be more politically conservative.

- What causes these people to be prejudiced?

- They tend to organize their world into ‘us’ versus ‘them’ groups and view the ‘them’ group as challenging cherished traditional values.

- They also tend to be more self-righteous and believe that they’re more moral than others.

- Cognitive distortions and expectations

- Much of prejudice is rooted in automatic cognitive processes that operate without conscious intent.

- Stereotyping plays a large role in prejudice.

- Competition between groups

- One study found that groups often respond more negatively to competition than individuals do.

- The lack of jobs or other important resources can also create competition between social groups.

- There’s ample evidence that conflict over actual and perceived scarcity of resources can prejudice individuals toward outgroup members.

- Threats to social identity

- Threats to social identity are more likely to provoke responses that foster prejudice and discrimination.

- When threatened, groups react in two ways.

- The most common response is to show ingroup favoritism by preferring group members over outgroup members.

- The second way to deal with threats to social identity is to engage in outgroup derogation by trashing outgroups that are perceived as threatening.

- Ingroups reward their own members and withhold rewards from outgroups, rather than deliberately blocking outgroups from desired resources.

- Authoritarianism

- Reducing prejudice

- Cognitive strategies

- This requires a shift from automatic processing of others to a controlled processing.

- Intergroup contact

- Talking up the other group’s good points and downplaying the bad points didn’t help.

- However, cooperating to reach common goals can reduce conflict if it results in successful outcomes and meaningful connections.

- Cognitive strategies

- Persuasion: the communication of arguments and information intended to change another person’s attitudes.

- Attitudes: beliefs and feelings about people, objects, and ideas.

- It’s assumed that attitudes predict behavior.

- Four elements of persuasion

- Source: person who sends a message.

- Persuasion tends to be more successful when the source has high credibility (expertise and trustworthiness).

- Trustworthiness is enhanced when people appear to argue against their own interests.

- Likeability is another major source factor and includes physical attractiveness and similarity.

- Receiver: person whom the message is sent to.

- Need for cognition: tendency to seek out and enjoy effortful thought, problem-solving activities, and in-depth analysis.

- Such people are more likely to be convinced by high-quality arguments than superficial analyses.

- When receivers are forewarned about a persuasion attempt, it’s becomes harder to persuade them.

- Message: the information transmitted by the source.

- Generally, two-sided arguments are more effective and it can increase credibility with your audience.

- Arousal of fear often increases persuasion too.

- Generating positive feelings is also an effective way to persuade people such as laughter.

- Channel: the medium through which the message is sent.

- Source: person who sends a message.

- Why are people persuaded sometimes?

- Elaboration likelihood model: a person’s thoughts about a persuasive message (rather than the actual message itself) will determine whether attitude change will occur.

- Persuasion can occur by two different routes: central and peripheral.

- The central route results in longer-lasting attitude changes and stronger attitudes than the peripheral route.

- For the central route to override the peripheral route, two requirements must be met

- Receivers must be motivated to process the persuasive message.

- Receivers must have the ability to grasp the message.

- Conformity: when people yield to real or imagined social pressure.

- People easily explain the behavior of others as conforming but don’t think of their own actions this way.

- People often believe that they’re alone in a crowd of sheep.

- Review of Asch’s conformity experiment.

- Subjects varied considerably in their tendency to conform.

- Group size and group unanimity are key determinants of conformity.

- As group size increases, conformity increases up to a point.

- Also, group size doesn’t matter if just one person disagrees with the others, breaking the unanimous agreement.

- Compliance: a type of conformity where private beliefs aren’t changed.

- E.g. Wearing a formal suit to work even though your personal belief is that you’d prefer not to.

- Normative influence: when people conform to social norms for fear of negative social consequences.

- Informational influence: when people look to others for how to behave in ambiguous situations.

- Bystander effect: the tendency for people to be less likely to provide help when others are present because they assume that someone else will provide help.

- E.g. No one calling emergency services because they assume someone else will.

- Thankfully, the bystander effect is less likely to occur when the need for help is very clear.

- Obedience: a form of compliance when people follow commands from someone in a position of authority.

- Review of Milgram’s shock experiment to test obedience.

- What caused the obedient behavior observed by Milgram?

- The demands escalated gradually so the strong shocks were only given after the participant was well into the experiment.

- Participants were told that the authority figure, not the person doing the shocking, was responsible if anything happened to the learner.

- Participants were evaluated in terms of the authority figure, not by their harmful effects on the victim.

- These findings suggest that human behavior is determined not by the kind of person one is, but instead the kind of situation one is in.

- Obedience research shows us the chilling fact that most people can be coerced into engaging in actions that violate their morals and values.

- Once people agree to something, they tend to stick with their initial commitment.

- Foot-in-the-door (FITD) technique: getting people to agree to a small request to increase the chances that they’ll agree to a larger request later.

- FITD is widely used in advertising to get people to commit to some request.

- E.g. Giving people a free trial before launching their hard sell.

- Why do FITD work? The best explanation is self-perception theory in that people sometimes infer their attitudes by observing their own behavior.

- Lowball technique: getting someone to commit to an attractive proposition before its hidden costs are revealed.

- E.g. Getting someone to buy a car but not revealing the hidden dealership costs.

- Lowballing is a surprisingly effective strategy to get someone to commit.

- Reciprocity principle: the rule that one should pay back in kind what one receives from others.

- E.g. Charities frequently make use of this principle.

- Door-in-the-face (DITF) technique: making a large request that is likely to be turned down to increase the chances that people will agree to a smaller request later.

- E.g. Starting with a high priced car but then trying to sell a lower priced car.

- DITF only works if there’s no delay between the two requests.

- Advertisers often try to artificially create scarcity to make their products seem more desirable.

- To be forewarned is to be forearmed.

Chapter 8: Interpersonal Communication

- Sometimes, it’s not so much what people say that matters, but how they say it.

- To be an effective communicator, you need to pay attention to both speaking and listening.

- Review of sender, receiver, message, noise, and channel.

- The primary means of sending a message is language, but people also communicate to others nonverbally through facial expressions, gestures, and vocal inflections.

- Nonverbal communication (NC): the transmission of meaning through symbols other than words.

- E.g. Smiling at an attractive stranger.

- General principles of nonverbal communication

- NC conveys emotions

- NC is multi-channeled

- NC is ambiguous

- NC may contradict verbal messages

- NC is culture-bound

- Personal space: a zone surrounding a person that “belongs” to them.

- Women seem to have smaller personal-space zones than men do as they tend to sit/stand closer together when talking compared to men.

- Facial expressions and the duration of eye contact are also important channels for NC.

- People typically maintain more eye contact when listening compared to talking.

- Culture strongly affects patterns of eye contact.

- Information can also be conveyed through body language and touch such as posture and hand gestures.

- There are also gender differences related to status and touch.

- E.g. Women use touch to convey closeness or intimacy, while men use touch as a means to control or indicate power.

- Intimate interactions can convey as much emotion as facial expressions.

- Paralanguage: all vocal cues other than the content of the verbal message itself.

- E.g. Grunts, sighs, murmurs, loudness/softness, speed, pitch, rhythm, accent, and complexity.

- Paralanguage can also communicate emotions.

- E.g. Faster speech may mean that the person is nervous, while slower speech might mean that the person is uncertain or that they want to emphasize a point.

- However, it’s easy to mistakenly assign meaning to voice qualities that aren’t valid.

- Detecting liars is difficult and even experts are only slightly better than chance.

- People overestimate their ability to detect liars as the cues are nonverbal and subtle, making them difficult to spot.

- Ways to improve communication

- Conversational skills

- Give to others what you would like to receive from them.

- Focus on the other person instead of yourself.

- Use nonverbal cues to communicate your interest in the other person.

- Self-disclosure: the act of sharing information about yourself with another person.

- Conversations with strangers and acquaintances typically start with superficial self-disclosure.

- Only when people have come to like and trust each other do they begin to share private information.

- Self-disclosure can lead to feelings of intimacy but it must be accompanied by how listeners respond too.

- Decreasing the breadth and depth of self-disclosures indicates that the person is emotionally withdrawing.

- Effective listening

- Listening and hearing are two different processes that are often confused.

- Hearing: a physiological process when sound waves hit our eardrums.

- Listening: a mindful activity that requires one to select and organize information, interpret and respond to communications, and recall what was has heard.

- Listening well is an active skill and effective listening is a vastly underappreciated skill.

- “We have two ears and one mouth, so we should listen more than we speak.”

- Because listeners process speech much more rapidly than people speak, it’s easy for listeners to become bored, distracted, and inattentive.

- Four points of being a good listener

- Signal your interest in the speaker by using nonverbal cues.

- Hear the other person out before you respond.

- Engage in active listening such as by asking questions and paraphrasing.

- Pay attention to the other person’s nonverbal signals.

- Conversational skills

- Two problems that interfere with effective communication

- Communication apprehension: anxiety caused by having to talk with others.

- Four responses to communication apprehension

- Avoidance: choosing not to participate.

- Withdrawal: when people unexpectedly find themselves trapped.

- Disruption: the inability to make fluent oral presentations.

- Overcommunication: talking nonstop.

- People with high communication apprehension are likely to have difficulties in relationships, work, and school.

- Barriers to effective communication

- Defensiveness: an excessive concern with protecting oneself from being hurt.

- Ambushing: listeners that are really just looking for an opportunity to attack a presenter.

- Motivational distortion: when people hear what they want to hear instead of what is actually said.

- Self-preoccupation: people who are so self-focused as to make two-way conversation impossible.

- You risk alienating others if you ignore the norm that conversations should involve a mutual sharing of information.

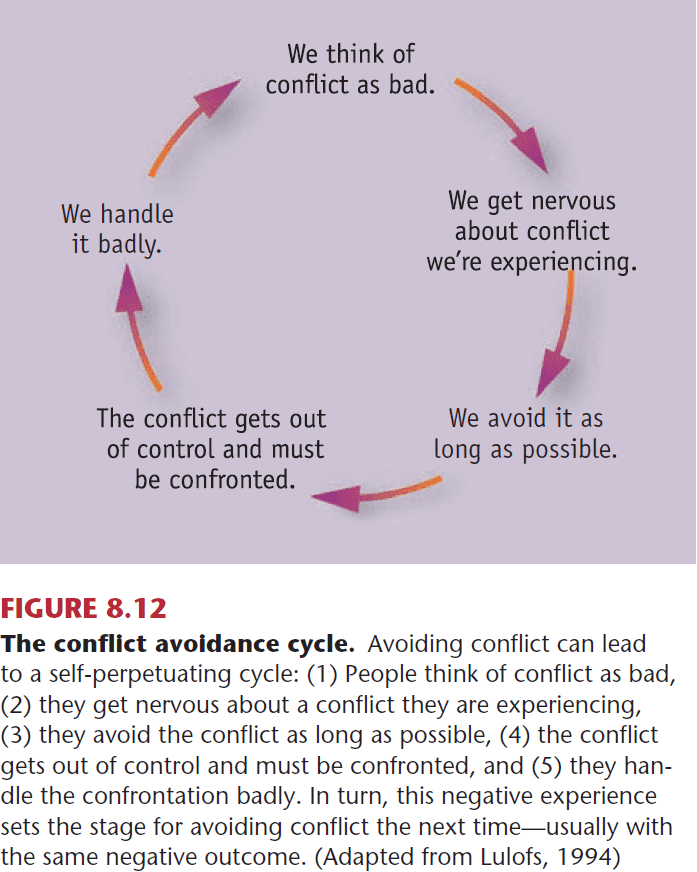

- People don’t have to be enemies to be in conflict, and being in conflict doesn’t make people enemies.

- Interpersonal conflict: whenever two or more people disagree.

- Conflict is neither good nor bad and may lead to either good or bad outcomes.

- When relationships and issues are important, avoiding conflict is generally counterproductive as it can lead to a self-perpetuating cycle.

- E.g. Japanese cultural style is to avoid conflict, while American values encourage competition and assertiveness.

- Valuable outcomes of confronting conflict

- Brings problems out into the open where they can be solved.

- Puts an end to chronic sources of discontent in a relationship.

- Lead to new insights through the sharing of divergent views.

- Five styles of managing conflict

- Avoiding/withdrawing (low concern for self and others)

- For minor problems, this is a good tactic as it saves time. For major problems, this isn’t a good strategy as it usually just delays the inevitable clash.

- Accommodating (low concern for self, high concern for others)

- Instead of ignoring disagreements, this person brings the conflict to a quick end by giving in easily.

- This is a poor way of dealing with conflict as it doesn’t generate creative thinking and effective solutions.

- Feelings of resentment may also develop.

- Competing/forcing (high concern for self, low concern for others)

- This person turns every conflict into a fight and must attain victory.

- This is also a poor way of dealing with conflict for the same reasons as accommodating.

- Compromising (moderate concern for self and others)

- This person is willing to negotiate and to meet the other person halfway.

- Each party gives up something so that both can have partial satisfaction.

- Collaborating (high concern for self and others)

- Whereas compromising is splitting the difference between positions, collaborating involves a sincere effort to find a solution that works optimally for both parties.

- This encourages openness and honesty and places importance on the other person’s ideas rather than the other person.

- This is the most productive style but takes the most time and effort.

- Avoiding/withdrawing (low concern for self and others)

- Assertiveness: acting in one’s own best interests by expressing one’s thoughts and feelings directly and honestly.

- Submissiveness: involves giving in to others on points of contention.

- The biggest problem with submissive people is that they can’t say no to unreasonable requests.

- The roots of submissiveness lie in excessive concern about gaining the social approval of others.

- Aggressiveness: involves saying and getting what one wants at the expense of others’ feelings and rights.

- The difference between assertiveness and aggressiveness is that one strives to respect others in the former.

- The challenge is to be firm and assertive without become aggressive.

- The important point with assertiveness is that you’re able to state what you want clearly and directly without overstepping others boundaries.

- A helpful way to distinguish among the three types of communication is in terms of how people deal with their own rights and the rights of others.

- Submissive people sacrifice their own rights.

- Aggressive people ignore the rights of others.

- Assertive people consider both their own rights and the rights of others.

Chapter 9: Friendship and Love

- People in close relationships spend a lot of time and energy maintaining the relationship.

- Close relationships are characterized by partners who are irreplaceable.

- E.g. Family, friendships, work relationships, romantic relationships, and marriages.

- Paradox of close relationships: close relationships can arouse intense feelings that are both positive and negative.

- E.g. Well-being, happiness, abuse, break-ups.

- Attraction: the initial desire to form a relationship.

- Three factors in attraction

- Proximity

- While this factor may seem self-evident, it’s sobering to realize that your friendships and relationships are often shaped by seating charts, apartment availability, shift assignments, and office locations.

- Familiarity

- Mere exposure effect: an increase in positive feelings toward a novel stimulus/person based on frequent exposure to it.

- Feelings arise on the basis of seeing someone frequently, and not because of any interaction.

- Physical attractiveness

- This factor plays a major role in initial face-to-face encounters.

- Four qualities that cause someone to be seen as more/less attractive: baby-face, mature features, expressiveness, and grooming.

- The desire for attractiveness is on the rise as more females get cosmetic surgery and more males get objectified for their body.

- Matching hypothesis: that people of similar levels of physical attractiveness gravitate toward each other.

- This hypothesis is supported by findings that both dating and married heterosexual couples tend to be similar in physical attractiveness.

- Physical attractiveness can be viewed as a resource that partners can exchange in relationships.

- Parental investment theory: a species’ mating patterns depend on what each sex has to invest to produce and nurture offspring.

- Males invest little beyond the act of copulation so their reproductive potential is maximized by mating with as many females as possible.

- Females invest heavily into producing and nurturing offspring so their reproductive potential is maximized by selectively mating with reliable partners who have greater material resources.

- However, there are alternatives to this theory such as sociocultural models.

- Proximity

- Two factors in getting acquainted

- Reciprocal liking

- “If you want to have a friend, be a friend.”

- This is a self-fulfilling prophecy as if you believe that someone likes you, you behave in a friendly manner towards them.

- Then your behavior encourages them to respond positively, which confirms your initial expectation.

- Playing hard to get is at odds with this factor and it usually turns people off.

- Perceived similarity

- Do people gravitate towards people who are more similar or different to themselves?

- E.g. Do “birds of a feather flock together” or do “opposites attract”?

- Research offers far more support for similar.

- Similarity plays a key role in attraction.

- Heterosexual married and dating couples tend to be similar in demographic characteristics (age, race, religion, socioeconomic status, education), physical attractiveness, intelligence, and attitudes.

- Reciprocal liking

- Relationship maintenance: the actions and activities used to sustain the desired quality of a relationship.

- The best predictors of marital satisfaction are positivity, assurances, and sharing tasks.

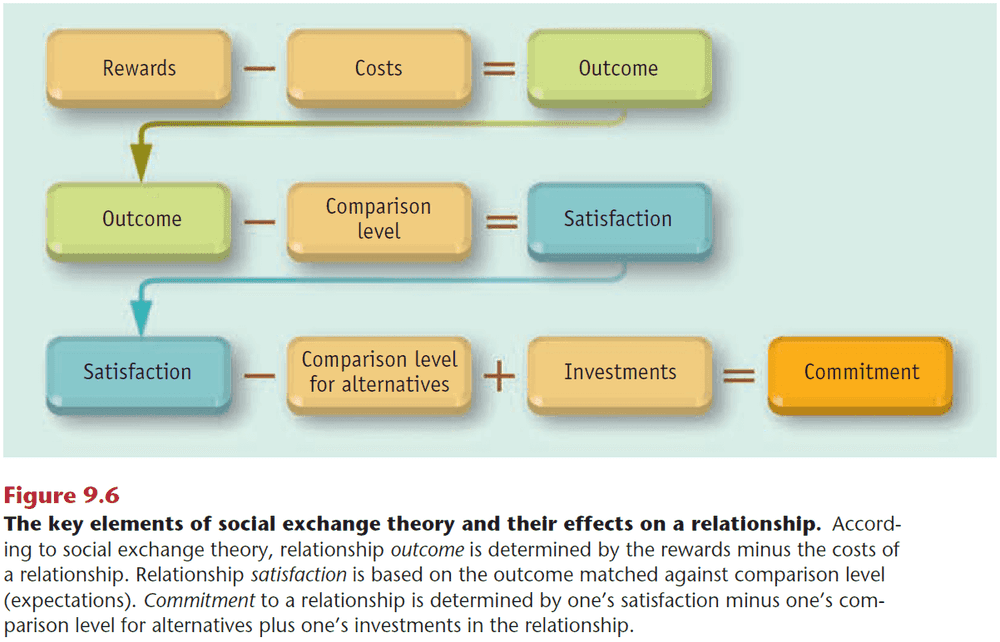

- How do you gauge your satisfaction in a relationship?

- One way is to weigh the rewards and costs exchanged in interactions.

- Comparison level: a personal standard of what constitutes an acceptable balance of rewards and costs in a relationship.

- If the rewards outweigh the costs, then the relationship will continue.

- Two factors in commitment

- Comparison level for alternatives: one’s estimation of the available outcomes from alternative relationships.

- This factor explains why many unsatisfying relationships don’t end until another love interest appears.

- This also explains a person leaving a happy relationship because it didn’t meet that person’s expectations and standards.

- Investments: things that people contribute to a relationship that they can’t get back if the relationship ends.

- Comparison level for alternatives: one’s estimation of the available outcomes from alternative relationships.

- Many people resist the idea that close relationships operate according to an economic model, but research supports this view.

- Importance of friends

- Give help in times of need

- Advice in times of confusion

- Consolation in times of failure

- Praise in times of achievement

- Friendship quality is predictive of overall happiness.

- What makes a good friend?

- Share news of success

- Show emotional support

- Volunteer help in times of need