Principles of Neural Science

By Eric Kandel, John D. Koester, Sarah H. Mack, Steven SiegelbaumNovember 09, 2021 ⋅ 343 min read ⋅ Textbooks

As the German neuroscientist Olaf Sporns has put it: "Neuroscience still largely lacks organising principles or a theoretical framework for converting brain data into fundamental knowledge and understanding." Despite the vast number of facts being accumulated, our understanding of the brain appears to be approaching an impasse.

Part I: Overall Perspective

- A first step towards understanding the brain is to learn how neurons are organized into signaling pathways and how they communicate by synaptic transmission.

- The specificity of the synaptic connections established during development and refined during experience underlie behavior.

Chapter 1: The Brain and Behavior

- The last frontier of biological science is to understand the biological basis of the mind: the brain.

- The current challenge is to unify psychology, the science of the mind, with neural science, the science of the brain.

- We assume that all behavior is the result of brain function.

- How do the billions of nerve cells in the brain produce behavior and cognition?

- What is the appropriate level of biological description to understand a thought, the movement of a limb, or the desire to make the movement?

- The appropriate level depends on the goal. Certain levels have more explanatory power than others.

- The goal of modern neural science is to integrate all of these specialized levels into a unified science.

- As we’ll see, questions about the levels of organization, specialization of cells, and localization of function recur throughout neural science.

- Review of the debate between Golgi and Cajal on the neuron doctrine, the principle that individual neurons are the elementary building blocks of the nervous system and aren’t a continuous web of tissue like blood vessels.

- Review of the history of neural science.

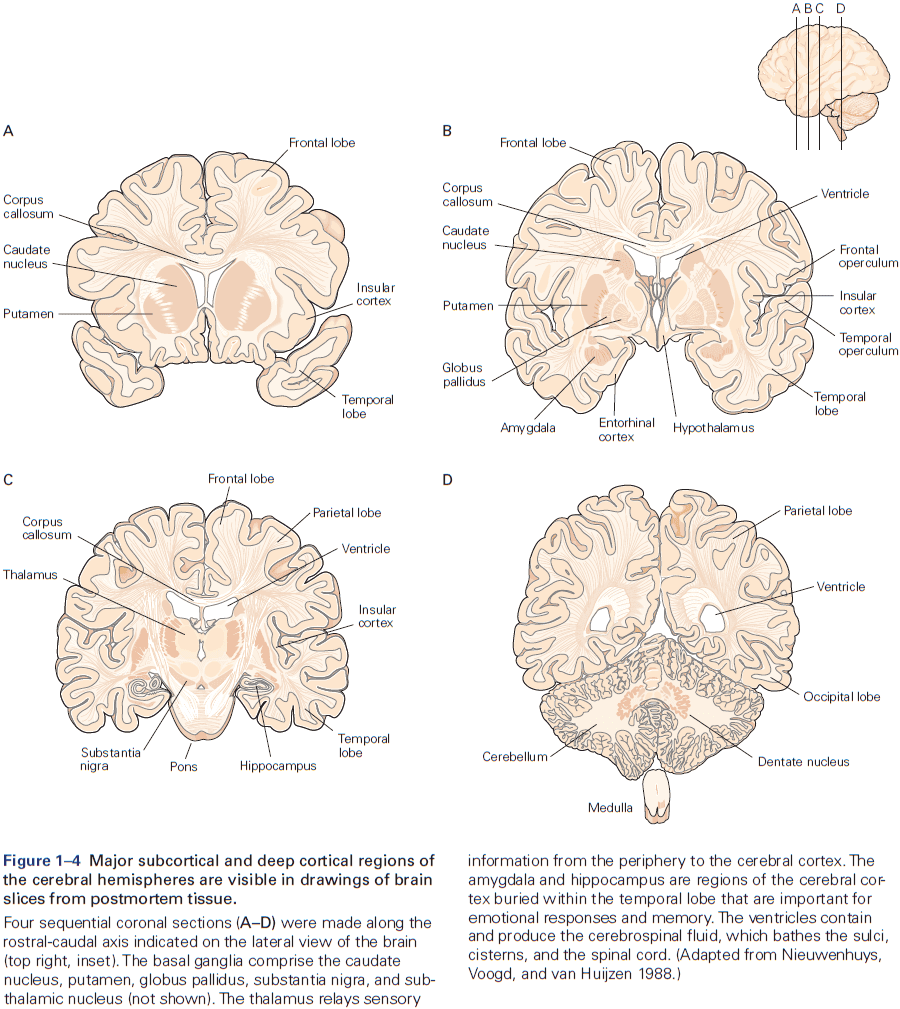

- Six major brain structures

- Medulla oblongata: directly rostral to the spinal cord and is responsible for vital autonomic functions.

- E.g. Digestion, breathing, and heart rate.

- Pons: conveys information about movement from the cerebral hemispheres to the cerebellum.

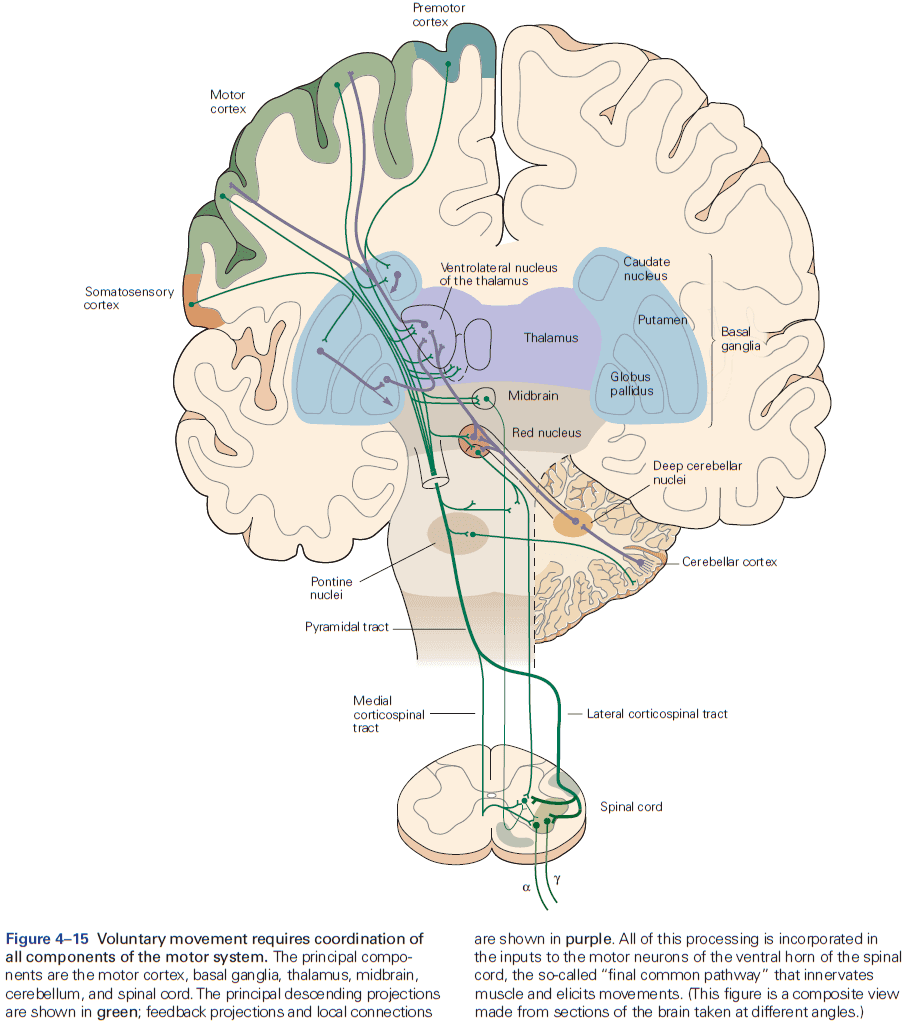

- Cerebellum: behind the pons, modulates the force and range of movement, and is involved in the learning of motor skills.

- Midbrain: rostral to the pons and controls many sensory and motor functions.

- E.g. Eye movement and the coordination of visual and auditory reflexes.

- Diencephalon: rostral to the midbrain and contains the thalamus and hypothalamus.

- Thalamus: processes most of the information reaching the cerebral cortex from the rest of the central nervous system.

- Hypothalamus: regulates autonomic, endocrine, and visceral functions.

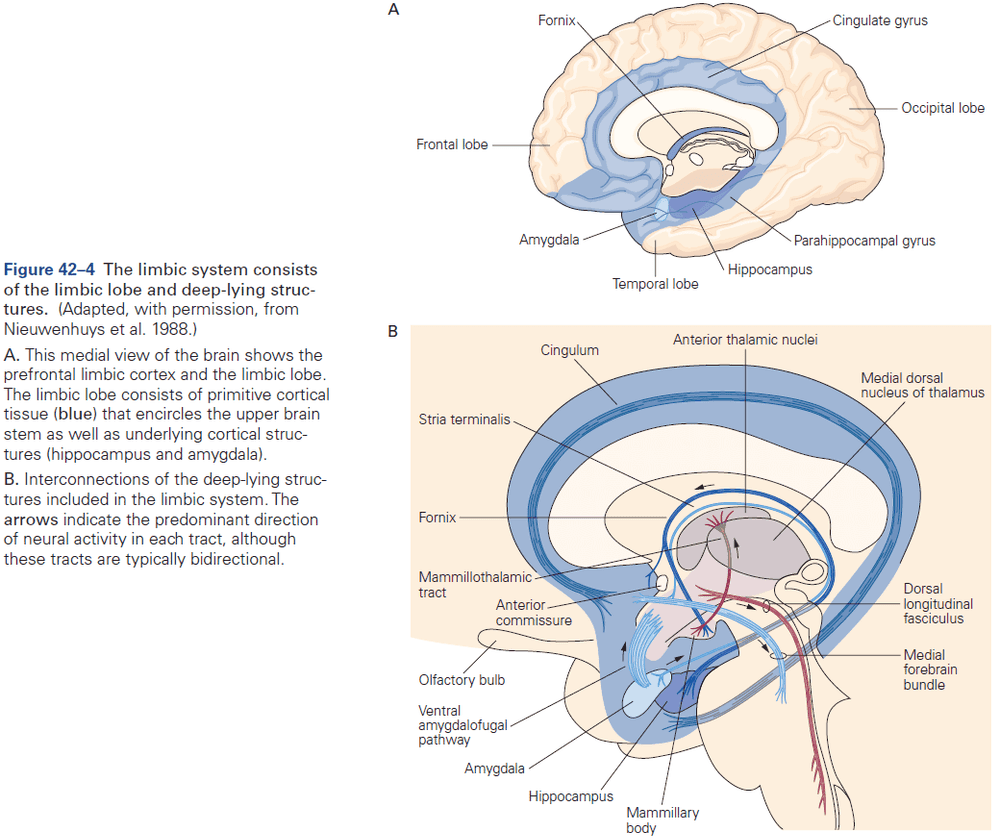

- Cerebrum: comprises two cerebral hemispheres and the basal ganglia, hippocampus, and amygdala.

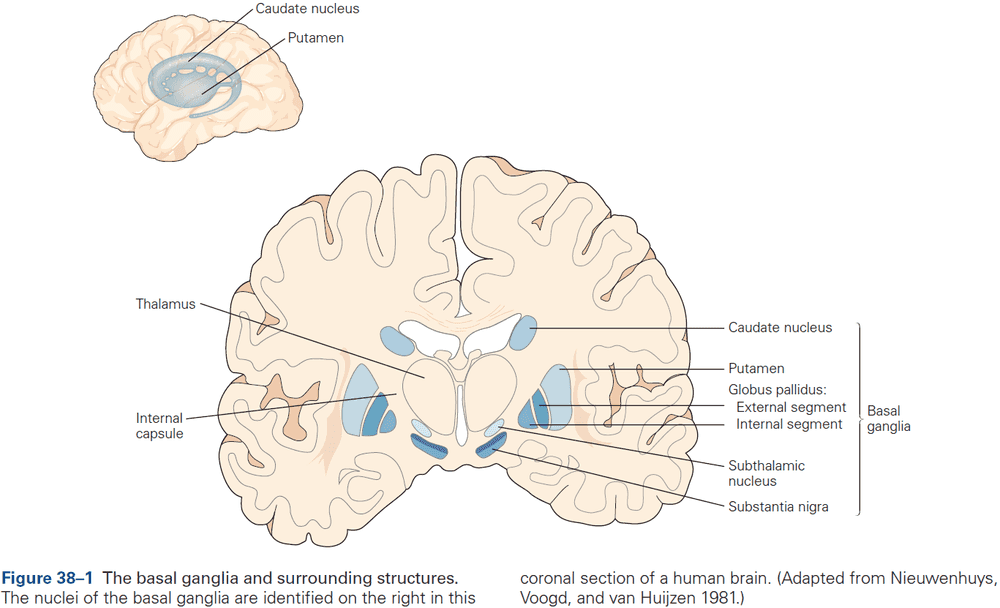

- Basal ganglia: regulates movement execution, motor- and habit-learning.

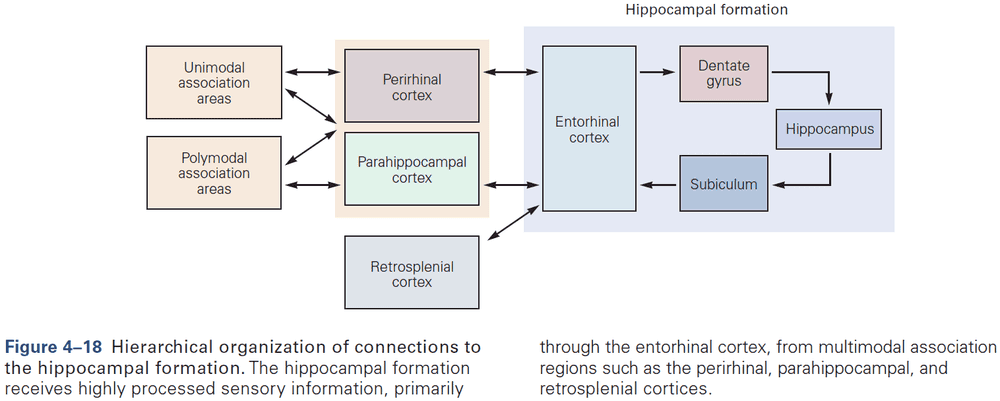

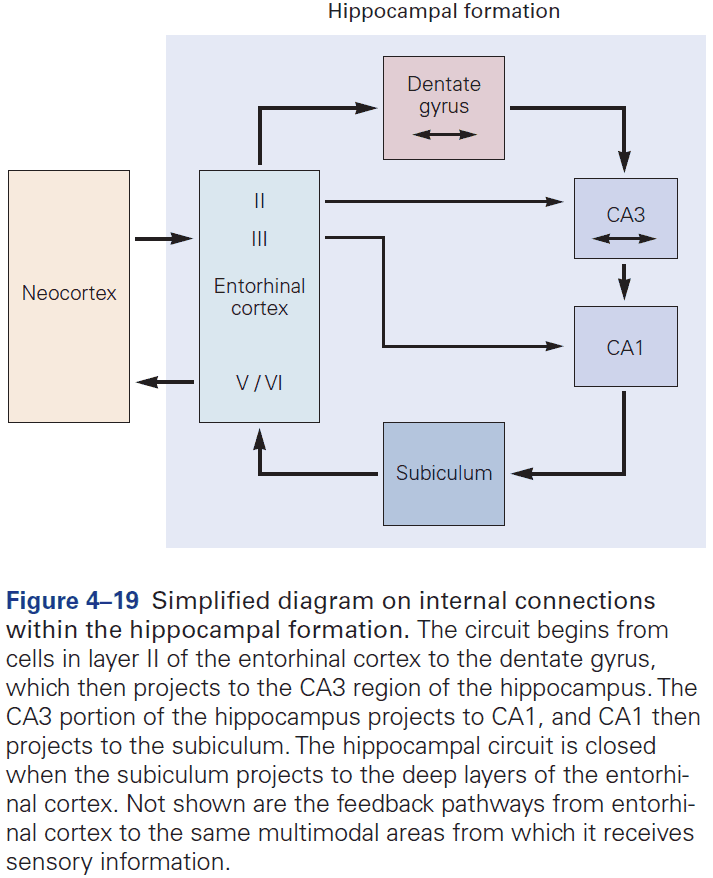

- Hippocampus: critical for the memory of people, places, things, and events.

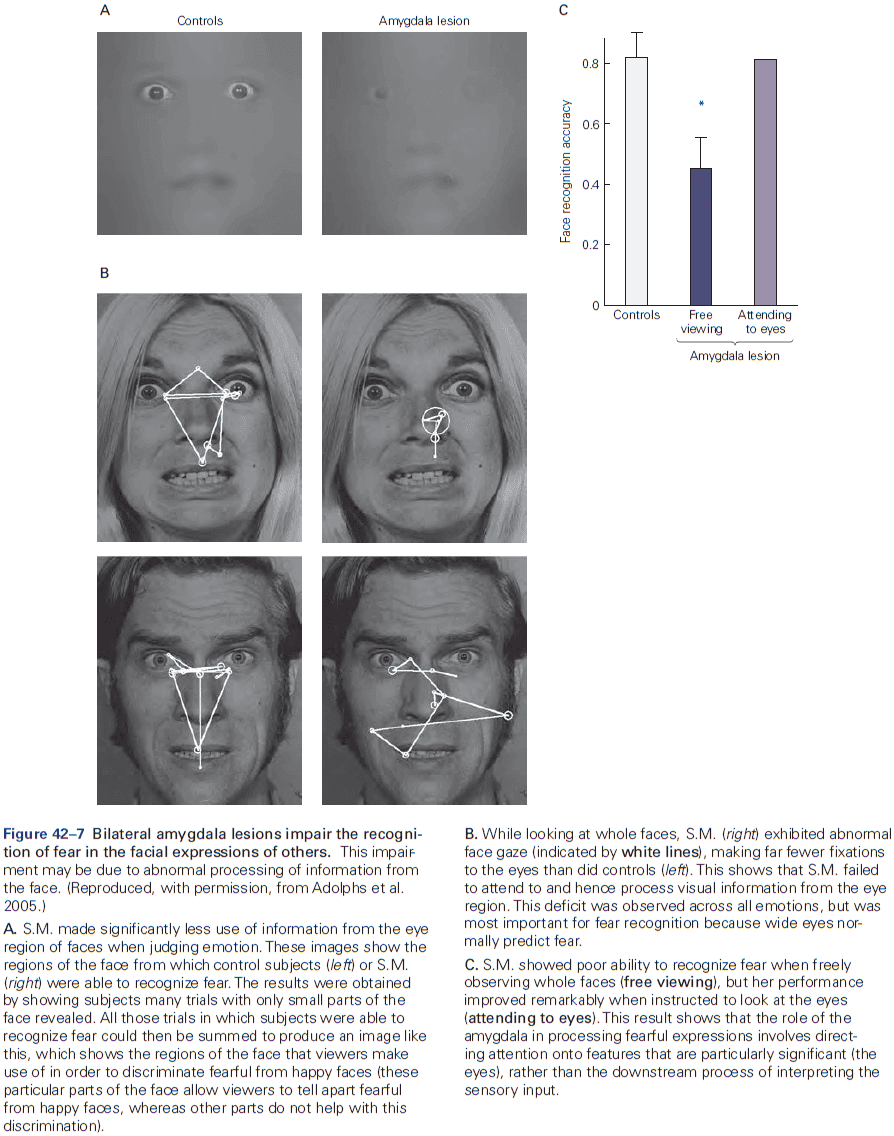

- Amygdala: coordinates the autonomic and endocrine responses of emotional states.

- Medulla oblongata: directly rostral to the spinal cord and is responsible for vital autonomic functions.

- Each of these structures is made up of distinct groups of neurons with distinct connectivity and developmental origins.

- E.g. In the medulla, pons, midbrain, and diencephalon, neurons are often grouped into distinct clusters termed nuclei.

- E.g. The surface of the cerebrum and cerebellum is a large, layered, folded sheet of neurons called the cerebral cortex and the cerebellar cortex respectively.

- The cerebrum also has a number of structures located below the cortex (subcortical).

- E.g. Basal ganglia and amygdala.

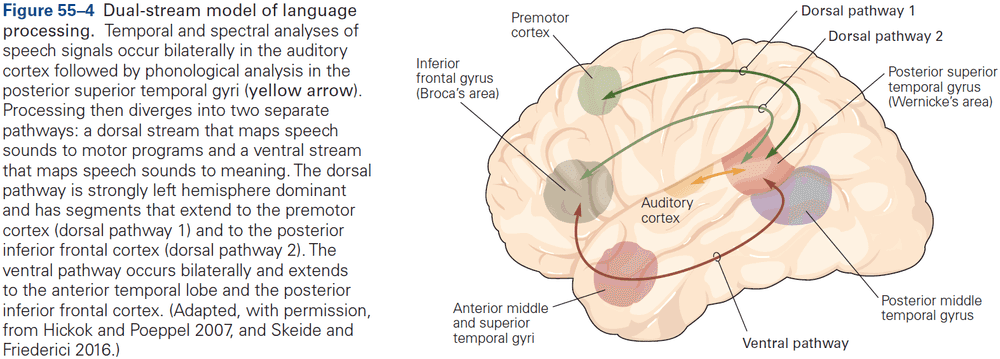

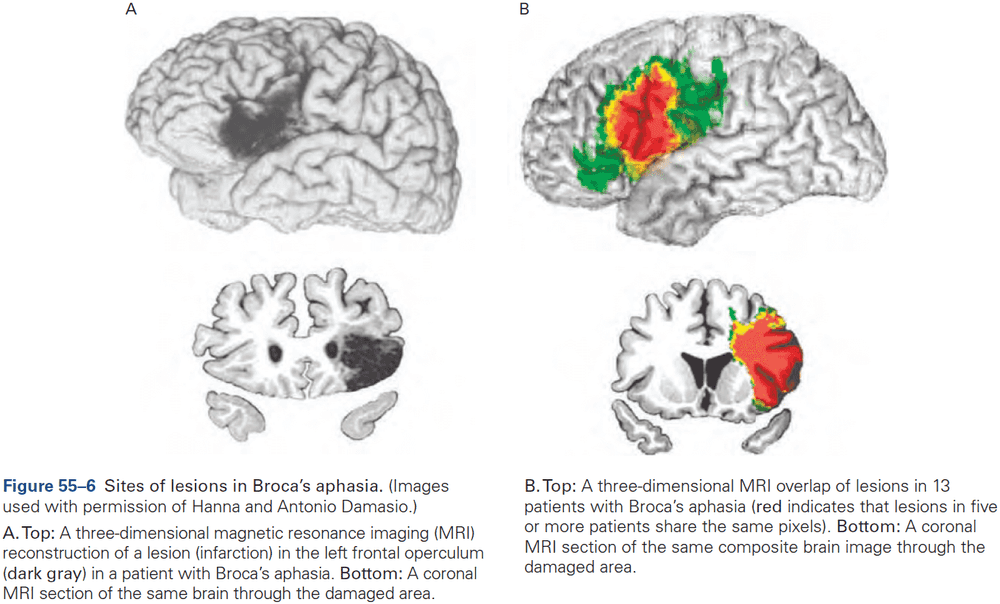

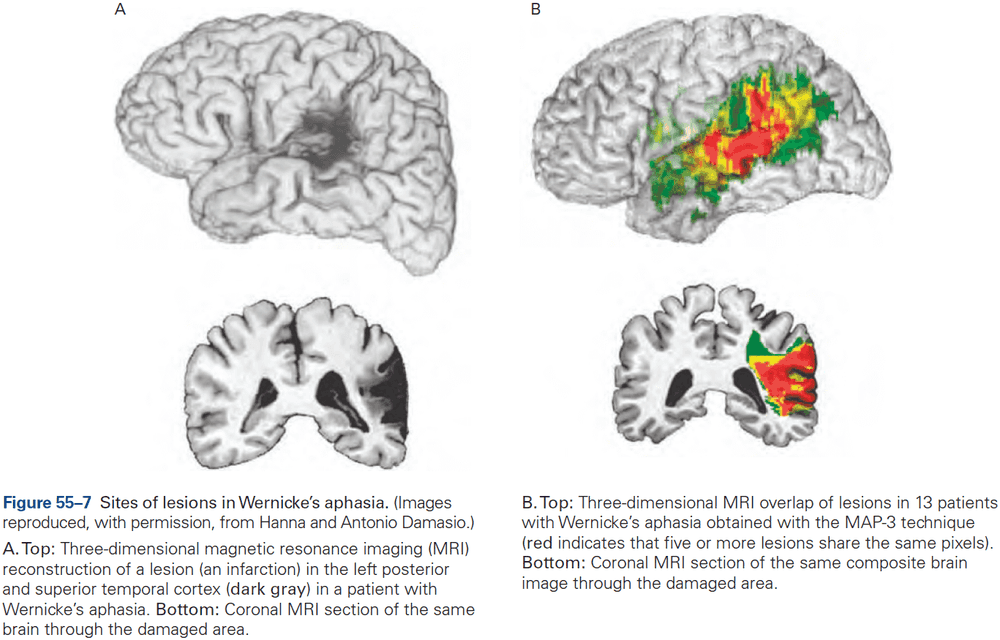

- The first strong evidence for localization of cognitive abilities came from studies of language disorders.

- Review of Broca’s and Wernicke’s work.

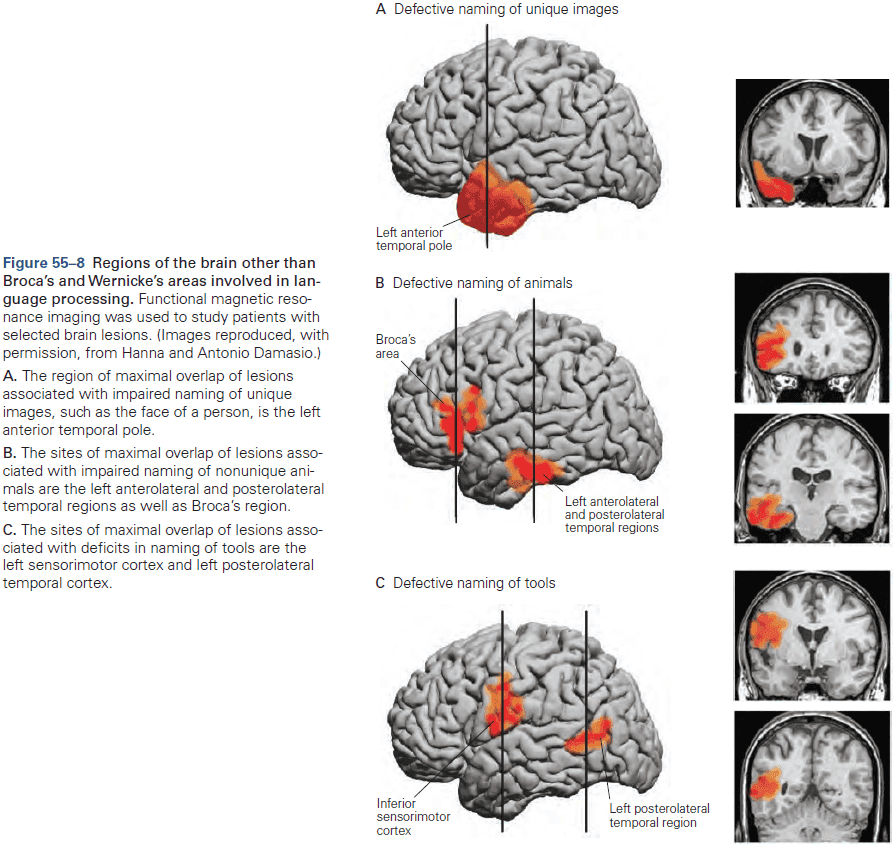

- The most basic mental functions, such as perception and motion, are mediated entirely by neurons in discrete local areas of the cortex.

- However, more complex cognitive functions, such as language and memory, result from interconnections between several functional sites.

- In other words, basic mental functions are localized while complex mental functions are distributed.

- The power of Wernicke’s model wasn’t only its completeness but also its predictive utility.

- E.g. It correctly predicted a third type of aphasia, one that results from the disconnection between both language areas.

- A given function may not be eliminated by a single lesion if it’s a complex and thus distributed function.

- Functional specialization is a key organizing principle in the cerebral cortex.

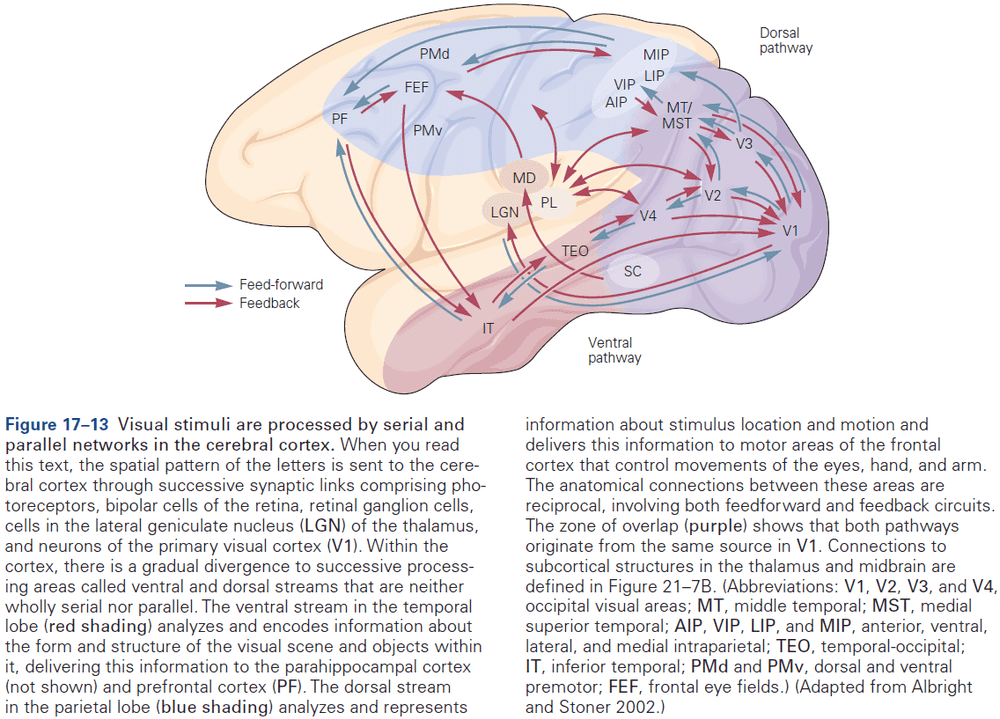

- Who would’ve guessed that the neural analysis of the movement and color of an object occurs in different pathways rather than a single pathway unified by the percept of the object.

- Similarly, the neural organization of language might not conform exactly to the axioms described by a theory of universal grammar, but it could still support the functionality described by it.

- Mental processes are the product of interactions between elementary processing units in the brain.

- We now think that all cognitive abilities result from the interaction of many processing mechanisms distributed in several regions of the brain.

- E.g. Perception, movement, language, thought, and memory are made possible by the integration of serial and parallel processing in discrete brain regions.

- So, damage to a single region doesn’t result in the complete loss of a cognitive function as many earlier neurologists believed.

- Instead of thinking of mental functions as a chain of nerve cells and brain areas, we should think of it as many parallel pathways in a network of modules that ultimately converge upon a common set of targets.

- Thus, malfunction of a single pathway within a network may affect the information carried by that pathway without disrupting the entire system.

- Our experience isn’t a faithful guide to how such processes occur in the brain.

- E.g. Recalling the concept ‘apple’ doesn’t help us understand how the concept was recalled.

- At present, there’s no satisfactory theory that explains why only some of the information that reaches our eyes leads to a state of subjective awareness, while other information doesn’t.

Highlights

- Neural science: to understand the brain at multiple levels of organization.

- E.g. From cell to circuit to operations of the mind.

- The fundamental principles of neural science bridge levels of time, complexity, and state.

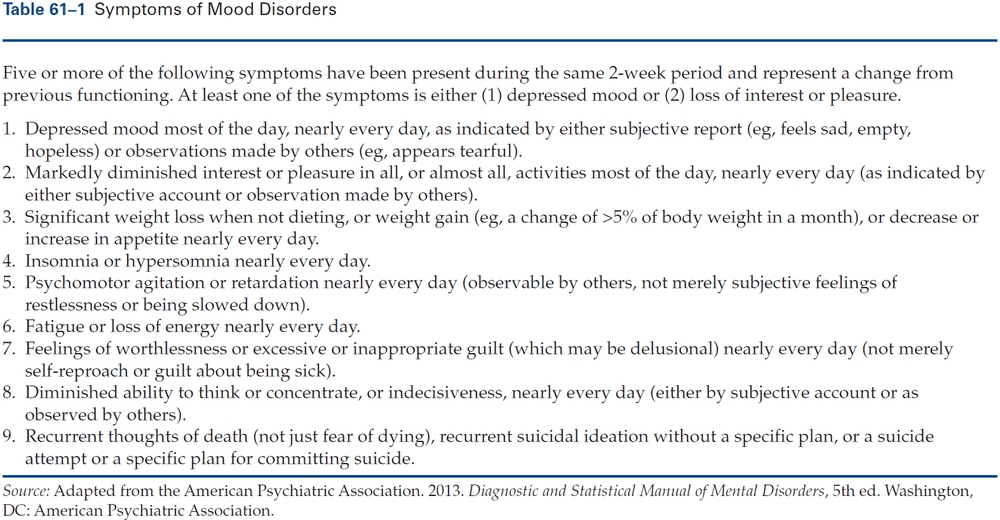

- E.g. From cell to action and ideation, from development to learning to expertise and forgetting, from normal function to neurological deficits and recovery.

- Neuron doctrine: that individual nerve cells (neurons) are the elementary building blocks and signaling elements of the nervous system.

- Neurons are organized into circuits with specialized functions, which integrate to form more complex cognitive functions.

- No area of the cerebral cortex functions independently of other cortical and subcortical structures.

Chapter 2: Genes and Behavior

- All behaviors are shaped by the interplay between genes, environment, and culture.

- Genes don’t directly control behavior but they do code for proteins and RNAs that act at different times and at many levels to affect the brain.

- This chapter asks how genes contribute to behavior.

- E.g. Brain development, genetic modifications in other animals, and genetic risk factors in neurodevelopmental and psychiatric syndromes.

- Heritability: the extent to which genetic factors account for traits in a population.

- Review of DNA, genes, transcription, translation, exons, and introns.

- The brain expresses a greater number of genes than any other organ in the body, and within the brain, diverse populations of neurons express different groups of genes.

- Genes not only specify the initial development and properties of the nervous system, they can also be changed by experience.

- Review of alleles, genotype (genetic makeup), phenotype (appearance), recessive and dominant.

- Completion of the human genome project in 2001 lead to a surprising conclusion: the unique human species didn’t result from the invention of unique human genes.

- E.g. Humans and chimpanzees share 99% of their protein-coding genes.

- The conclusion is that ancient genes that humans share with other animals are regulated in new ways to produce new human adaptations.

- Because of this conservation of genes throughout evolution, insights from studies of one animal can often be applied to other animals with related genes.

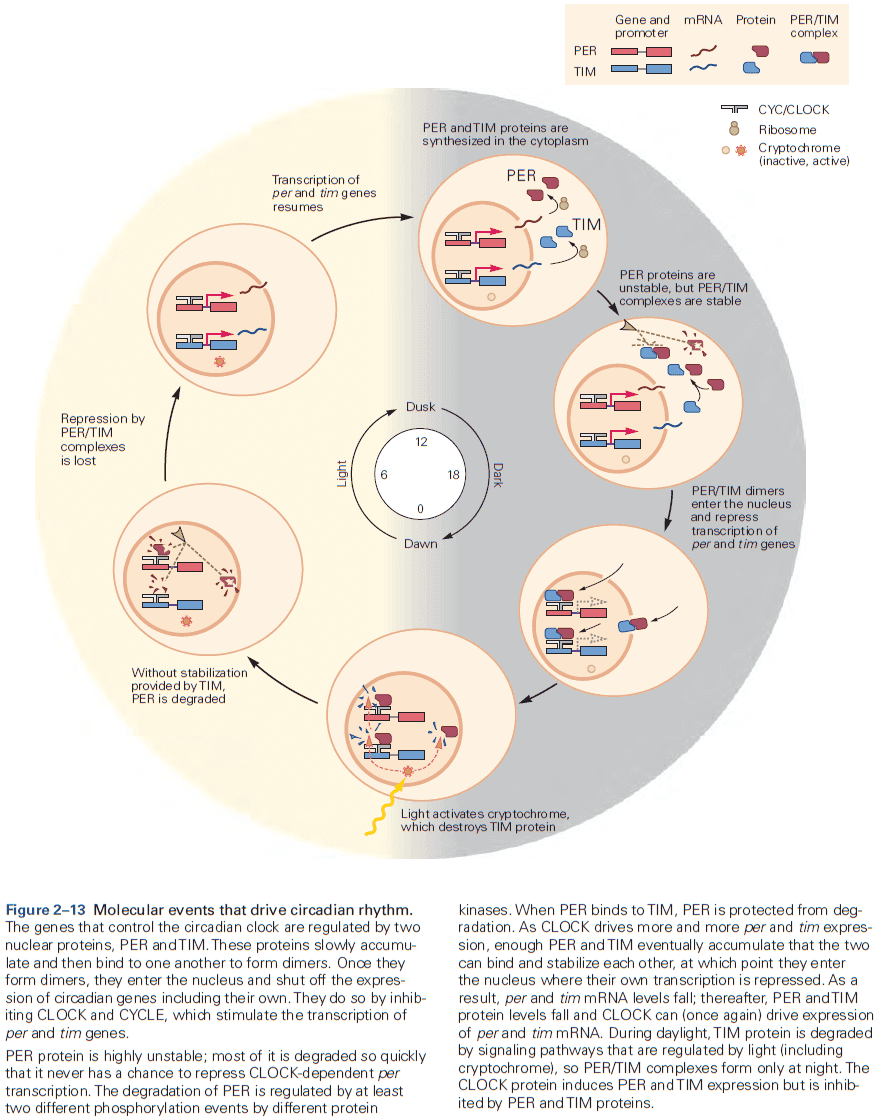

- We have a mostly complete picture of the genetic basis of the circadian control of behavior.

- The core of circadian regulation is an intrinsic biological clock that oscillates over a 24-hour cycle and persists in the absence of light.

- A group of genes, not one gene, are conserved regulators of the circadian clock.

- Molecules such as protein kinases are particularly significant at transforming short-term neural signals into long-term changes in the property of a neuron or circuit.

- Examples of links between genetics and behavior

- The ‘for’ gene regulates the activity level and locomotion in Drosophila and in bees to be either sitters or rovers.

- The ‘npr-1’ gene encodes a neuropeptide receptor that regulates social behavior in C. elegans.

- Other neuropeptides have been implicated in the regulation of mammalian social behavior such as oxytocin and vasopressin in prairie voles.

- The ‘PKU’ gene, when it interacts with dietary protein, causes intellectual disability.

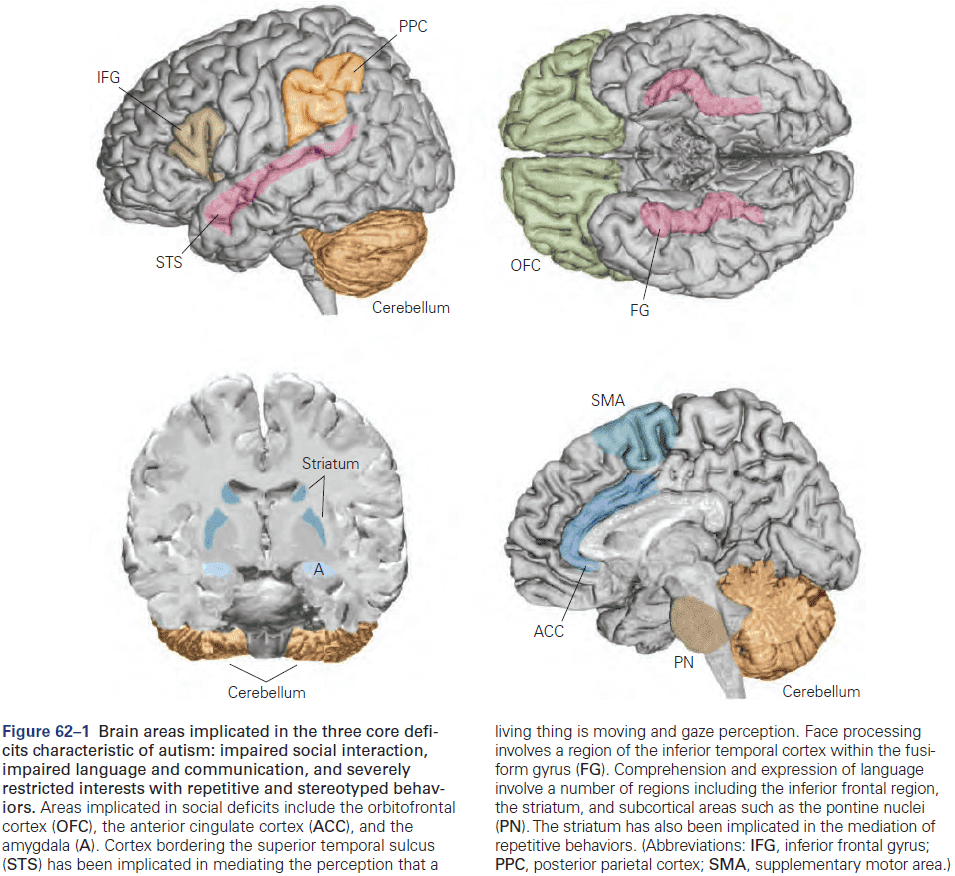

- Genetic links between autism spectrum disorder and Williams syndrome further supports that the domains of cognitive and behavioral functioning are different, but may share important molecular mechanisms.

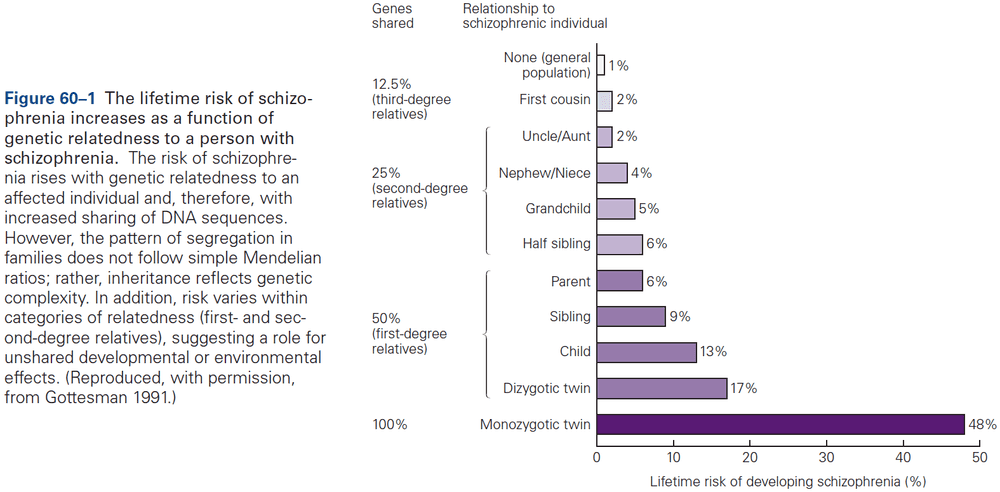

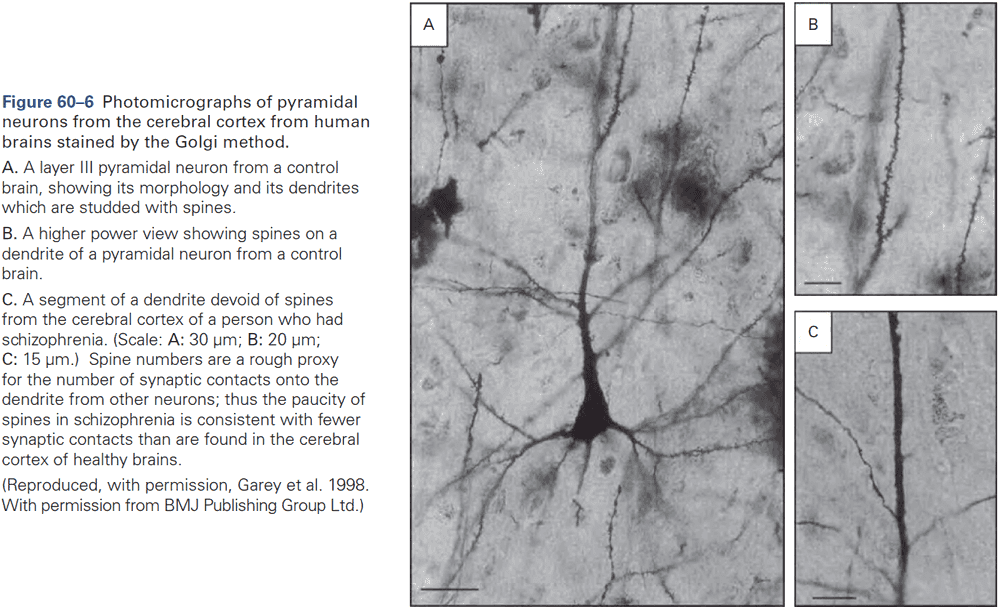

- Skipping the rest of the chapter on genetics applied to autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia due to disinterest.

Highlights

- Rare genetic syndromes have provided important insights into the molecular mechanisms of complex human behaviors.

- E.g. Fragile X syndrome, Rett syndrome, and Williams syndrome.

- Sequencing the human genome, development of high-throughput genomic assays, and simultaneous computing and methodological advances have lead to profound changes in our understanding of the genetics of human behavior and psychiatric illness.

- E.g. Schizophrenia and autism.

Chapter 3: Nerve Cells, Neural Circuitry, and Behavior

- The brain both gathers and discards a lot of information.

- Neurons are the basic signaling units of the brain.

- The human brain has at least 86 billion neurons that can be classified into at least a thousand different types.

- Yet this great variety of neurons is less of a contributor to the complexity of human behavior than their organization into anatomical circuits with precise functions.

- E.g. Similar neurons can produce different actions because of the way they’re connected.

- Five basic features of the nervous system

- Structural components of individual neurons.

- Mechanisms behind neurons producing signals within themselves and between each other.

- Pattern of connection between neurons and between neurons and their targets.

- Relationship of different patterns of interconnection to different types of behavior.

- How neurons and their connections are modified by experience.

- Two main classes of cells in the nervous system

- Neurons (nerve cells): the signaling units of the nervous system.

- Glia (glial cells): supports neurons.

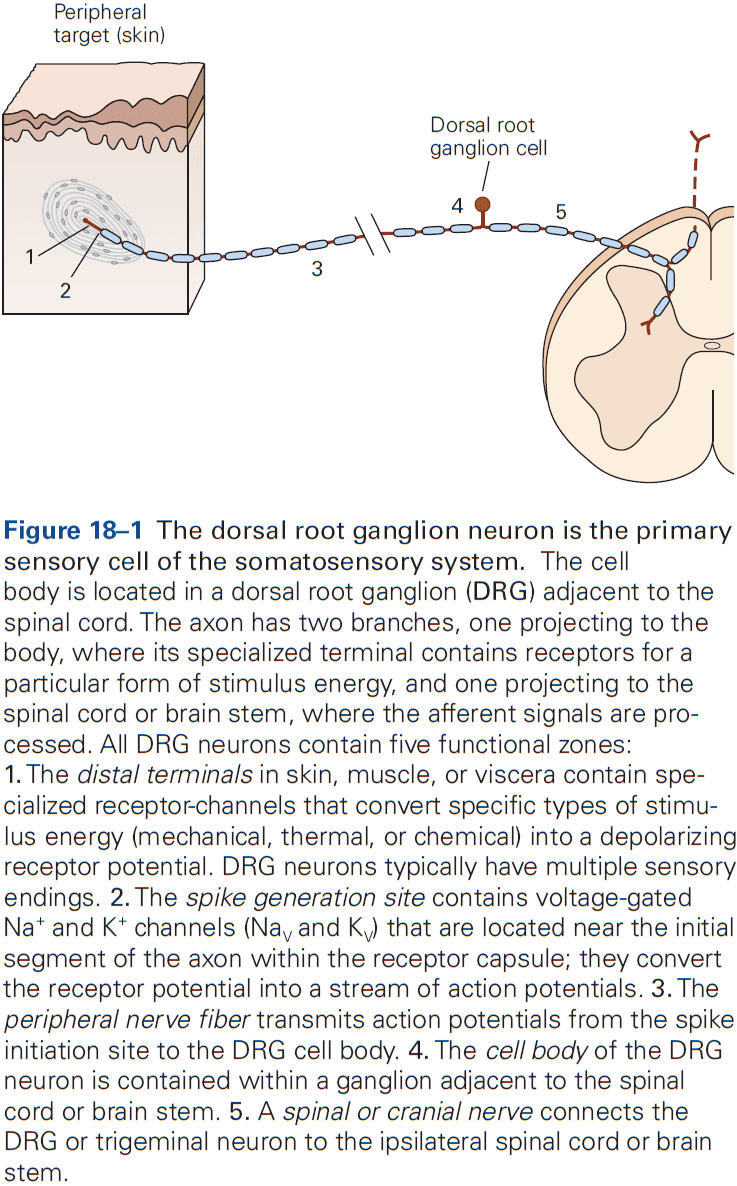

- Review of soma, dendrites, axon, presynaptic terminals, and action potential (AP).

- The axon typically extends some distance away from the cell body before it branches, allowing it to carry signals to many target neurons.

- The amplitude of an AP remains constant at 100 mV because it’s an all-or-none impulse that’s regenerated at regular intervals along the axon.

- APs are the signals that the brain uses to receive, analyze, and convey information.

- E.g. The APs that convey information about vision are identical to those that carry odor information.

- Since all APs are the same, the type of information conveyed by an AP isn’t determined by the form of the signal, but by the pathway the signal travels in the brain.

- Thus, the brain analyzes and interprets patterns of incoming electrical signals carried over specific pathways, and creates our sensations of sight, touch, taste, smell, and sound.

- Review of myelin sheath, nodes of Ranvier, synapse, synaptic cleft, pre- and post-synaptic neuron and terminal, excitation and inhibition.

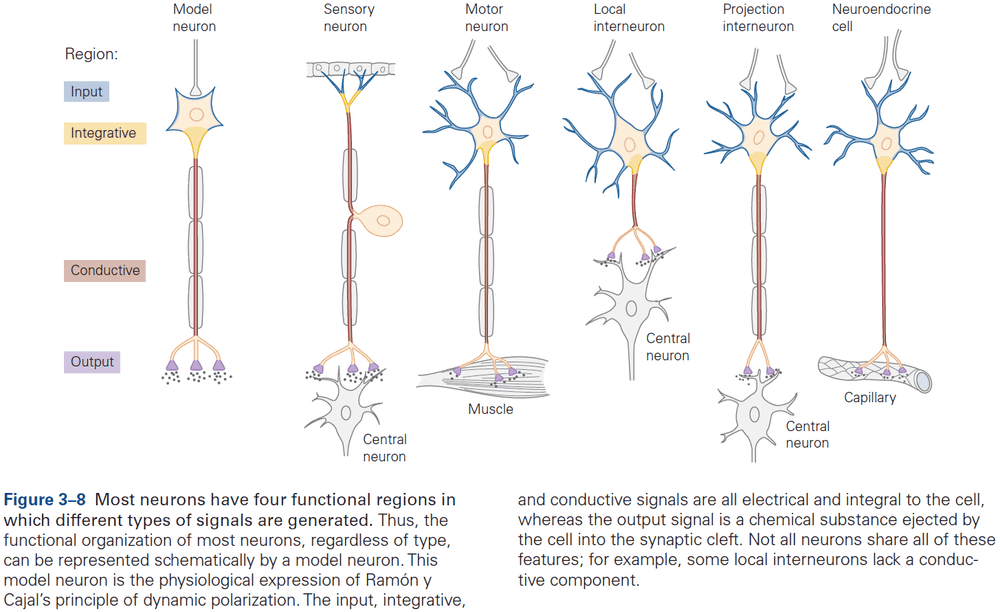

- Principle of dynamic polarization: electrical signals within a neuron flow in only one direction, from the postsynaptic neuron to the axon.

- In most neurons studied to date, electrical signals only travel in one direction in the axon.

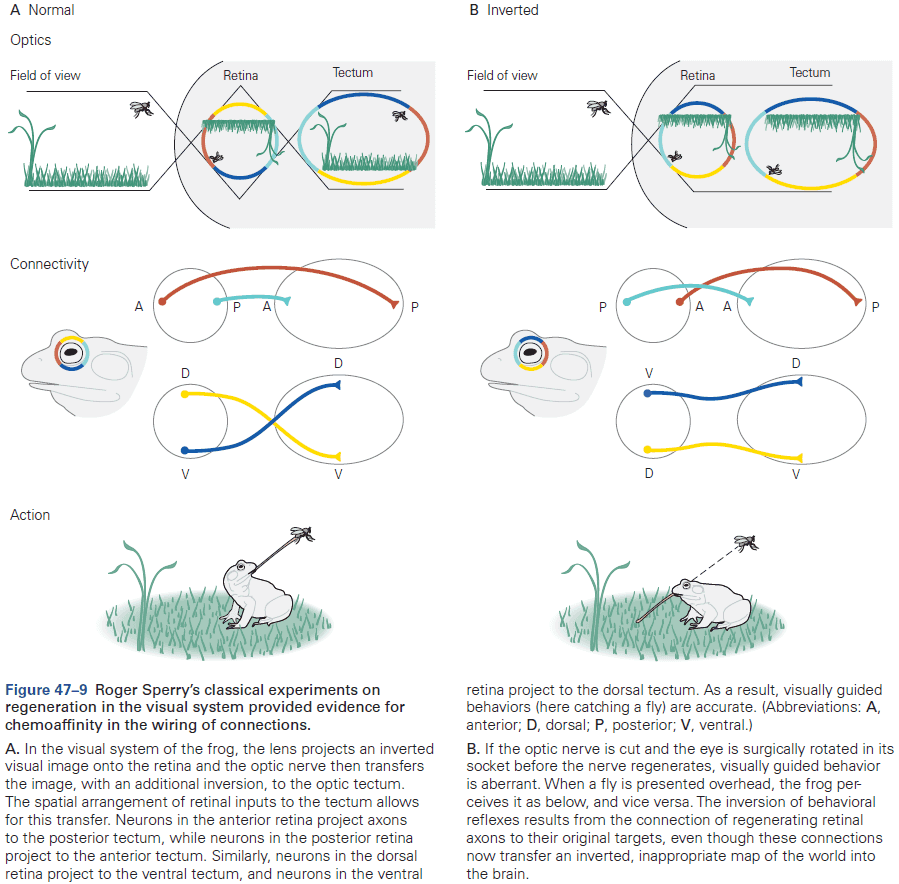

- Connectional specificity: neurons don’t randomly connect with each other but make specific connections with certain postsynaptic target cells and not others.

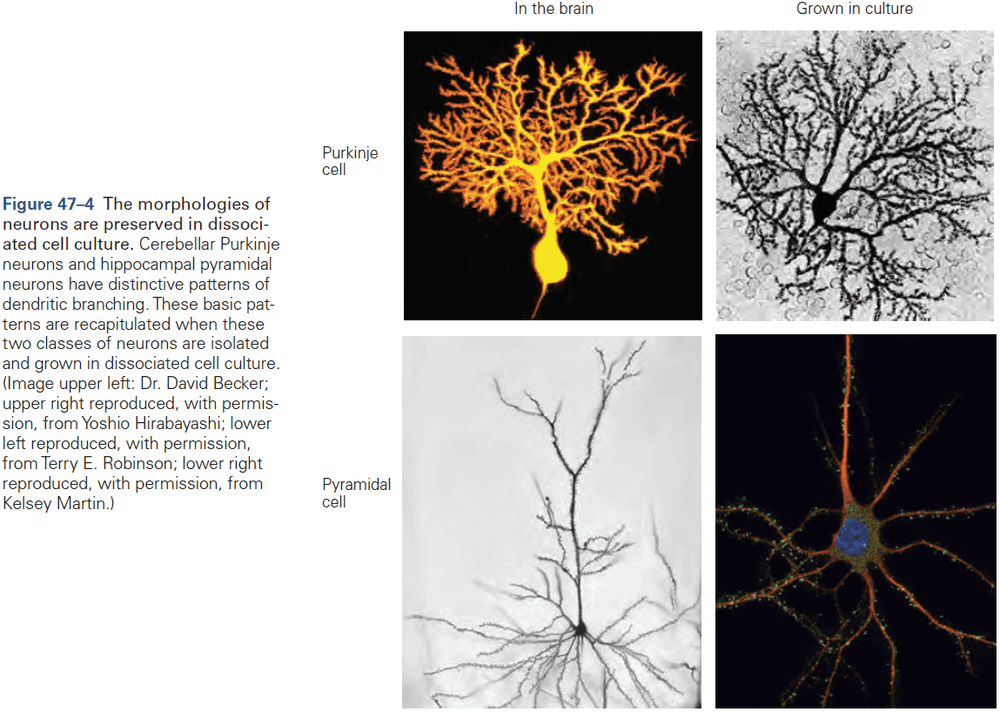

- The feature that most distinguishes one type of neuron from another is form, specifically the number and order of dendrites and axon.

- E.g. Unipolar, bipolar, and multipolar neurons.

- Unipolar neurons show up in our autonomic nervous system, bipolar neurons show up in sensory organs, and multipolar neurons dominate the nervous system of vertebrates.

- Multipolar cells vary greatly in shape.

- E.g. Length of axons, extent, dimensions, and intricacy of dendritic branching.

- Usually, the extent of branching correlates with the number of synaptic contacts that other neurons make onto them.

- E.g. A spinal motor neuron can receive 10,000 contacts while a Purkinje cell can receive as many as a million contacts.

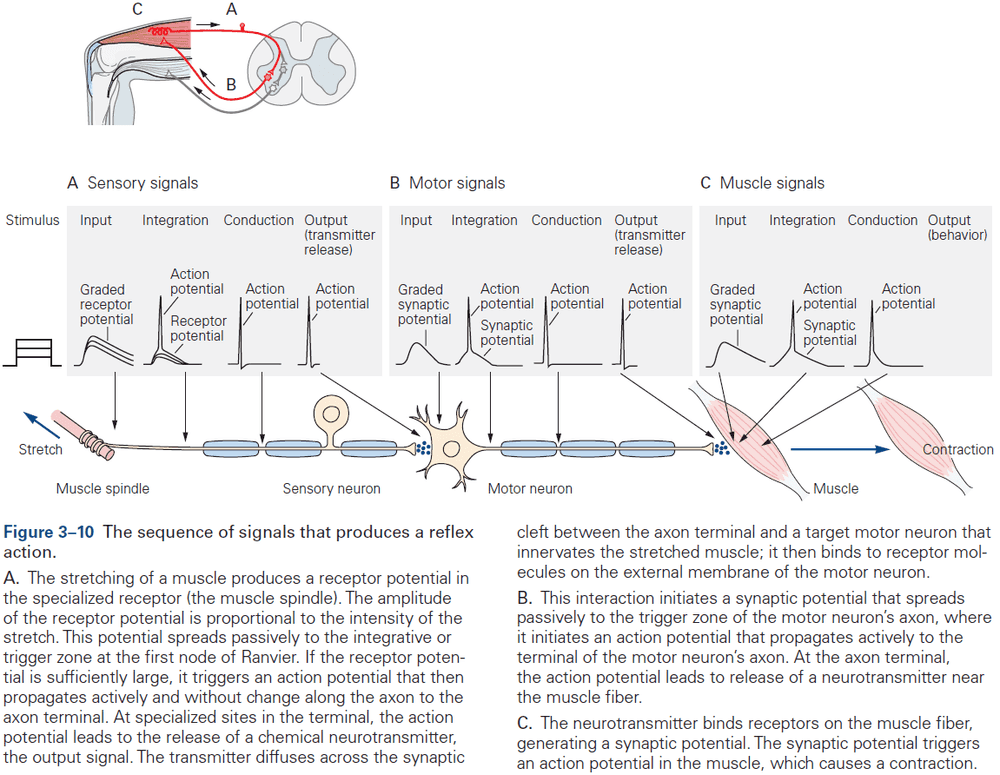

- Review of sensory neurons, motor neurons, interneurons, afferent (towards CNS), efferent (away CNS).

- Interneurons are the most numerous and are subdivided into two classes

- Relay/Projection: long axons to convey signals over long distances, from one brain region to another.

- Local: short axons that form connections with nearby neurons in local circuits.

- Glia surround cell bodies, axons, and dendrites of neurons and differ morphologically from neurons in that they don’t form dendrites and axons.

- Glia also differ functionally as they don’t have the same membrane properties as neurons and aren’t electrically excitable.

- Every behavior is mediated by a specific set of interconnected neurons, and every neuron’s behavioral function is determined by its connections with other neurons.

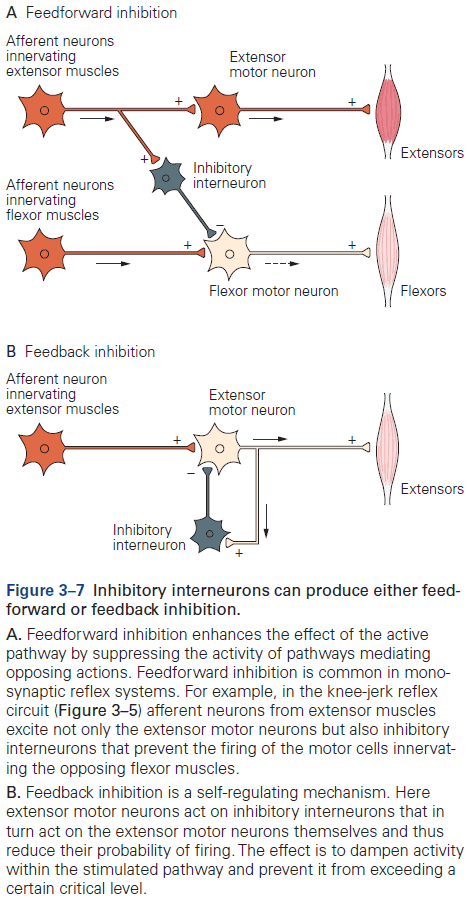

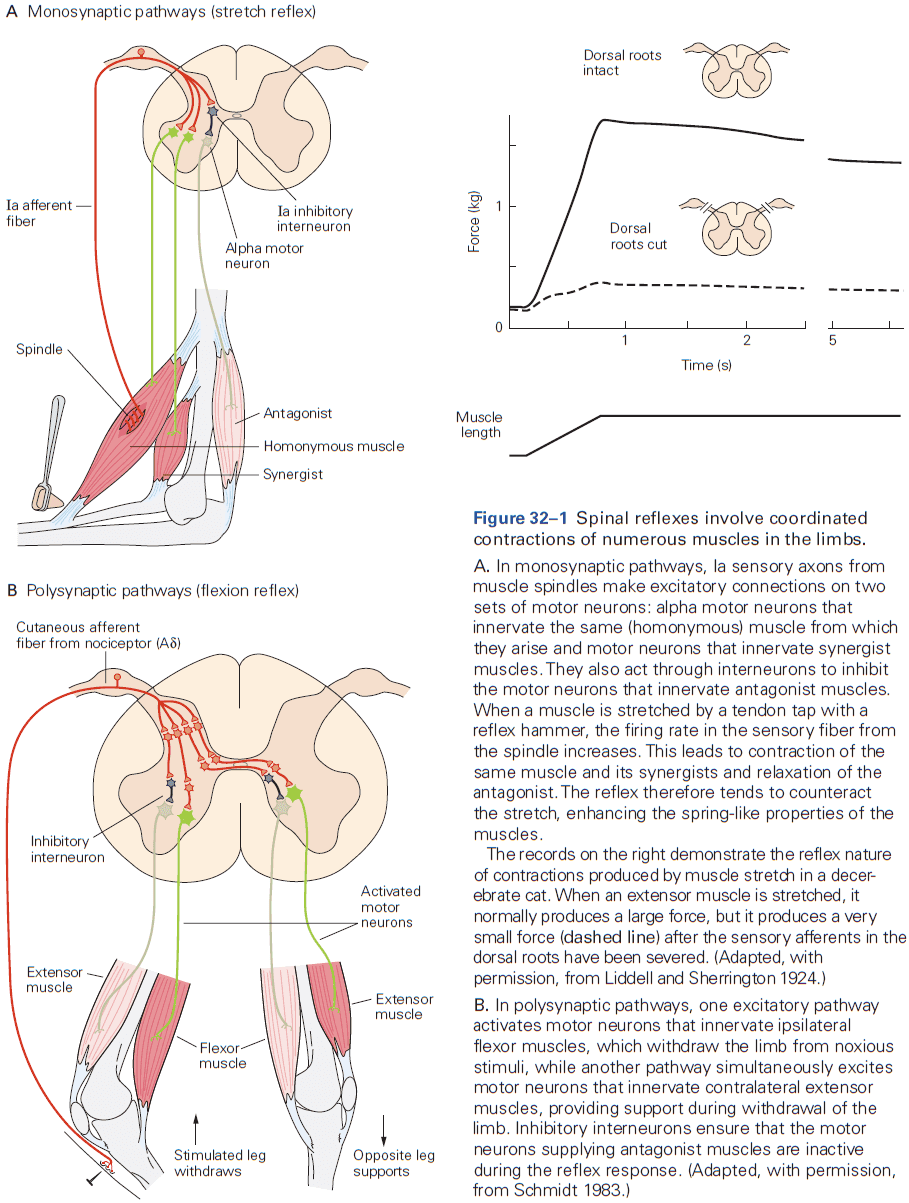

- Review of the knee-jerk reflex, divergence, convergence, feedforward and feedback inhibition, and resting membrane potential (-65 mV).

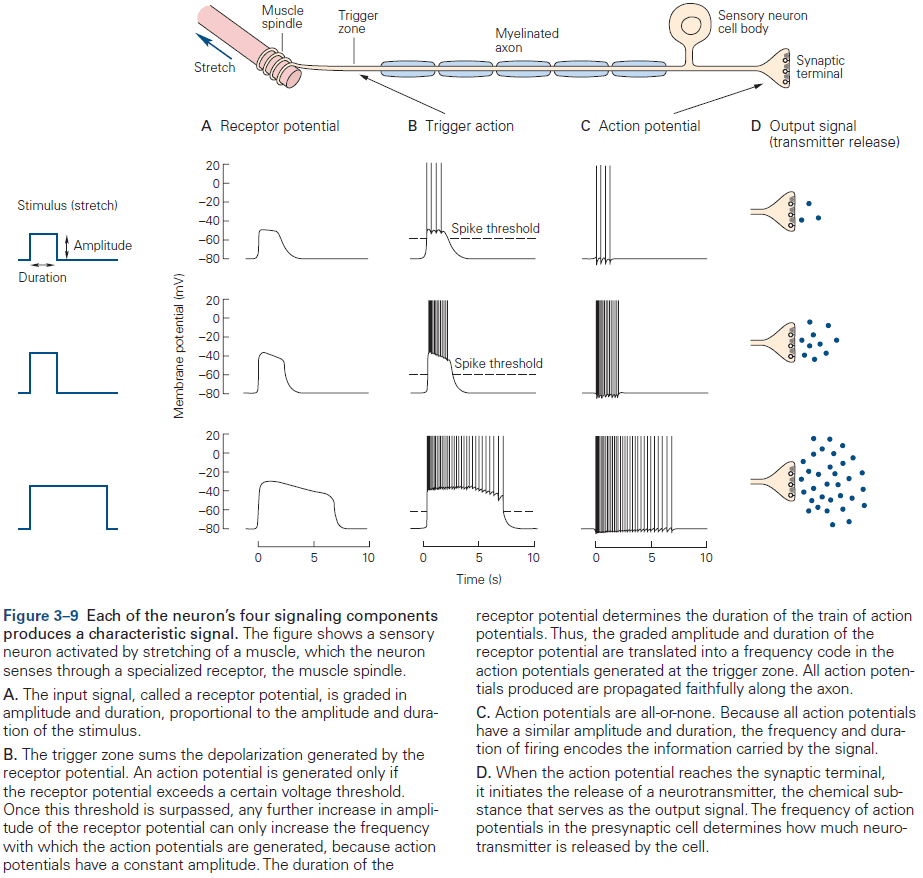

- Signaling is organized in the same way in all neurons

- A receptive component for producing graded input signals.

- A summing or integrative component that produces a trigger signal.

- A conducting long-range signaling component that produces all-or-none conducting signals.

- A synaptic component that produces output signals to the next neuron or muscle or gland.

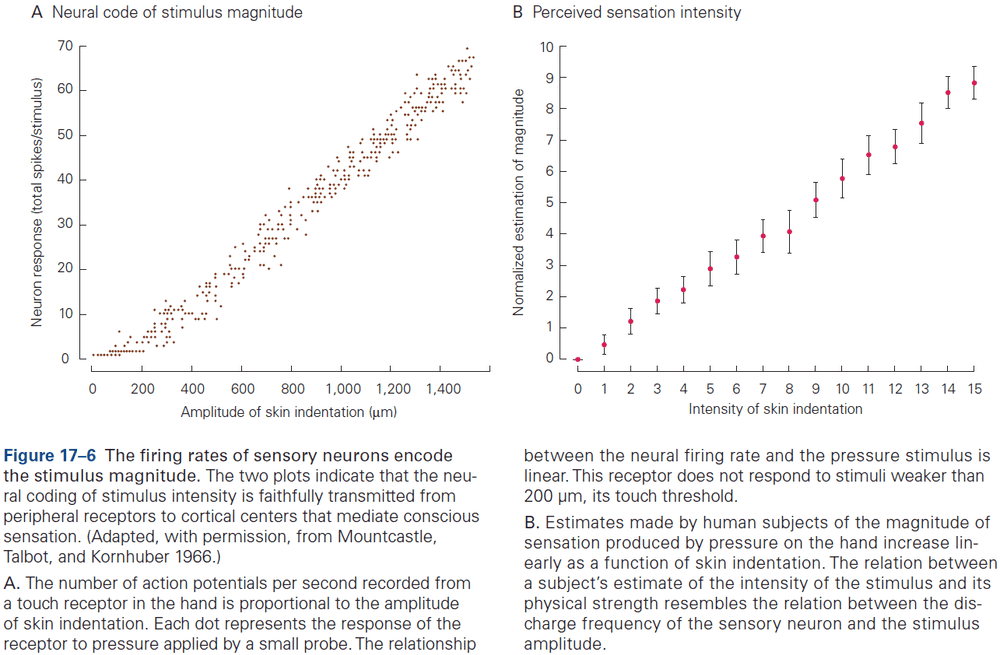

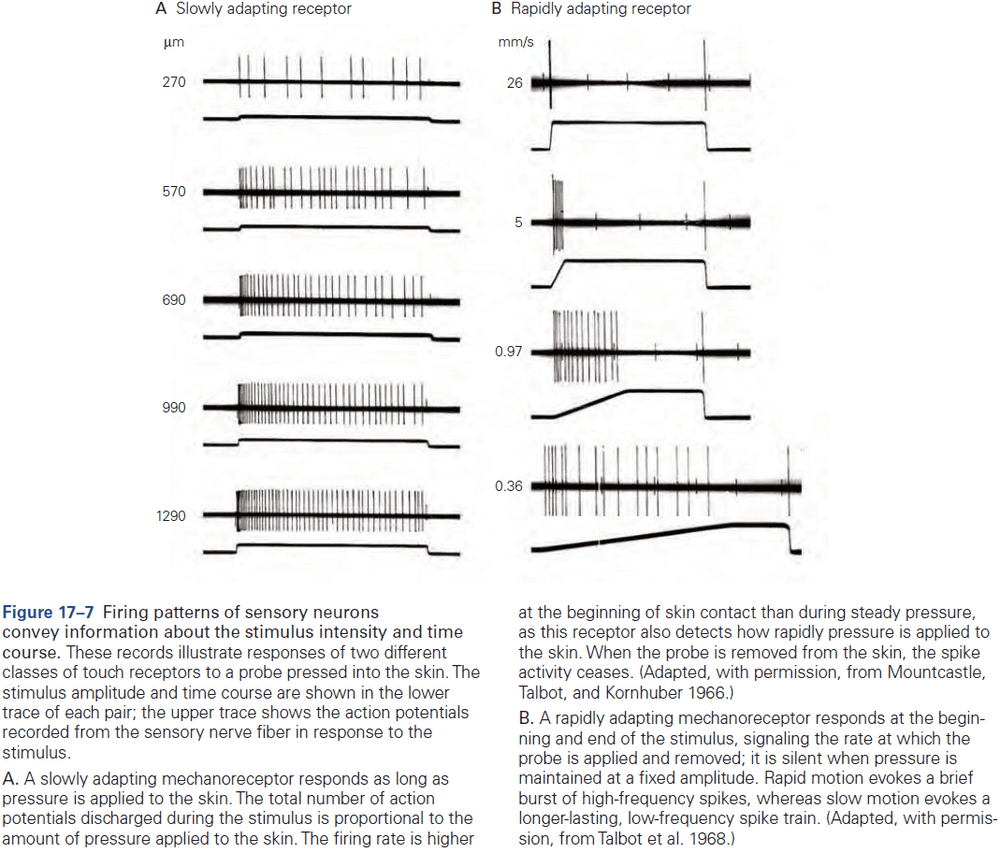

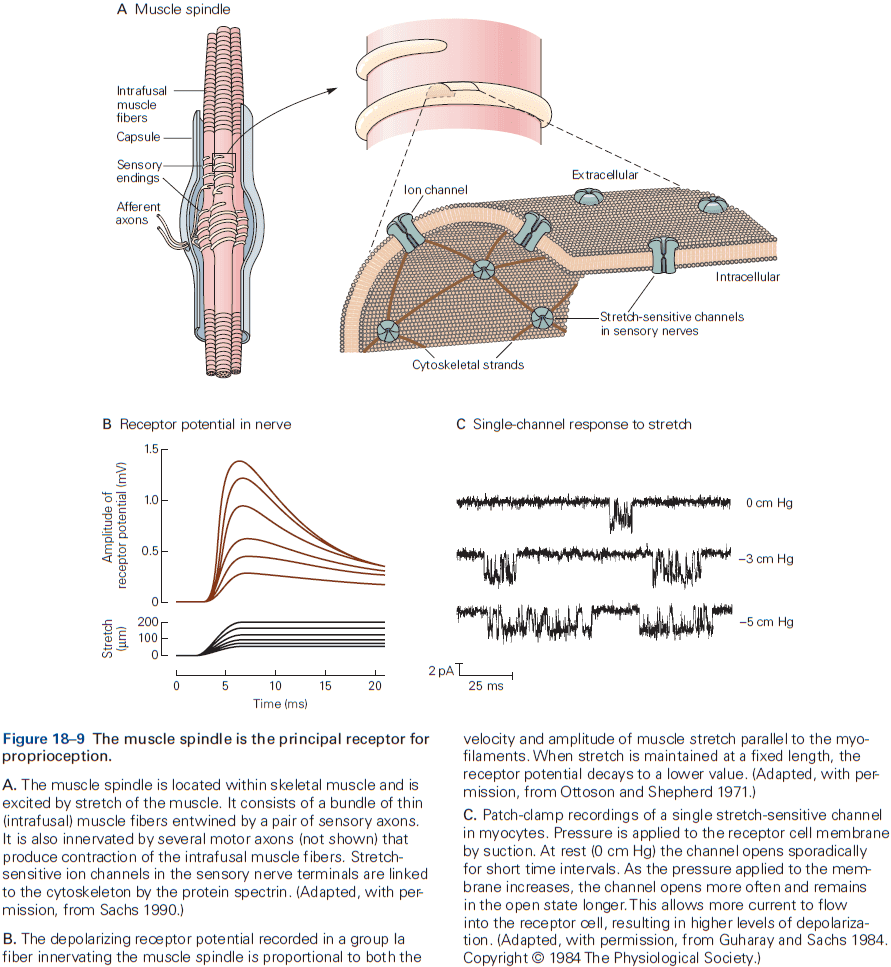

- Receptor potential: a change in membrane potential at a sensory receptor.

- The amplitude and duration of a receptor potential depends on the intensity of the signal.

- Unlike APs, receptor potentials are graded and are either depolarizing or hyperpolarizing.

- The receptor potential is the first representation of a stimulus to be coded in the nervous system.

- However, since the receptor potential isn’t regenerated like an AP and spreads passively, it doesn’t travel far.

- To be successfully carried to the spinal cord, the local signal must be amplified and it must be converted into APs.

- Synaptic potential: when a neurotransmitter alters the membrane potential of the postsynaptic cell.

- Like the receptor potential, the synaptic potential is graded and its amplitude depends on how much transmitter is released.

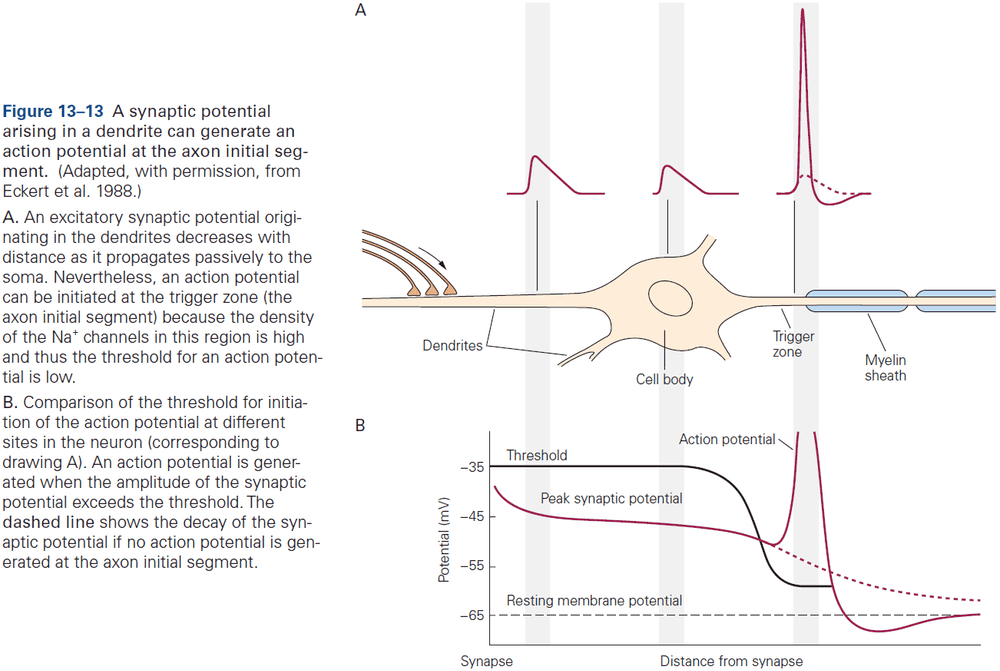

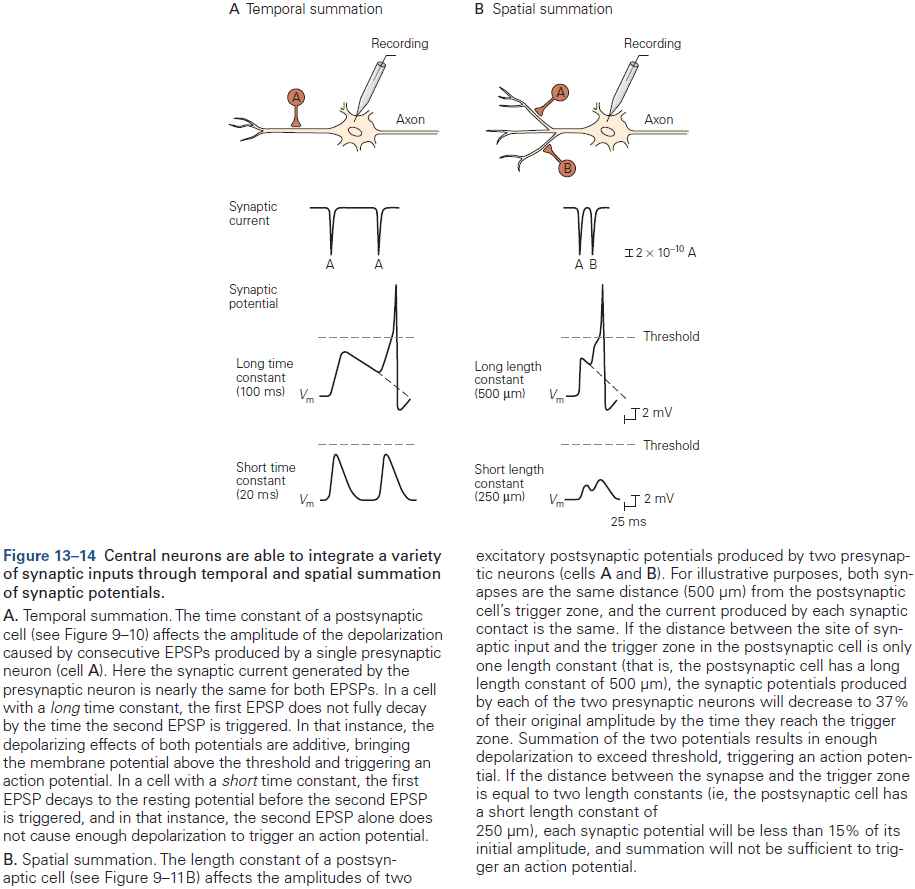

- Signals from dendrites are integrated at the axon trigger zone where the activity of all receptor or synaptic potentials is summed and, if the sum reaches threshold, where the neuron generates an AP.

- APs carried into the nervous system by a sensory axon are often indistinguishable from those carried out of the nervous system to muscles.

- Two features of AP trains

- Number of APs (counters)

- Time intervals between them (timers)

- What determines the intensity of sensation or speed of movement is the frequency of APs.

- What determines the duration of sensation or movement is the period of time that APs are generated.

- The pattern of APs also conveys important information.

- E.g. Spontaneous, regularly active neurons (beating) and brief bursts of APs (bursting).

- If APs are stereotyped and only reflect the most elementary properties of the stimulus, then how do they carry the rich variety of information needed for complex behavior?

- The answer is simple and is one of the most important organizational principles of the nervous system.

- Interconnected neurons form anatomically and functionally distinct pathways and it’s these pathways of connected neurons, not individual neurons, that convey information.

- E.g. The neural pathways activated by receptor cells in the retina that respond to light are completely distinct from the pathways activated by sensory cells in the skin that respond to touch.

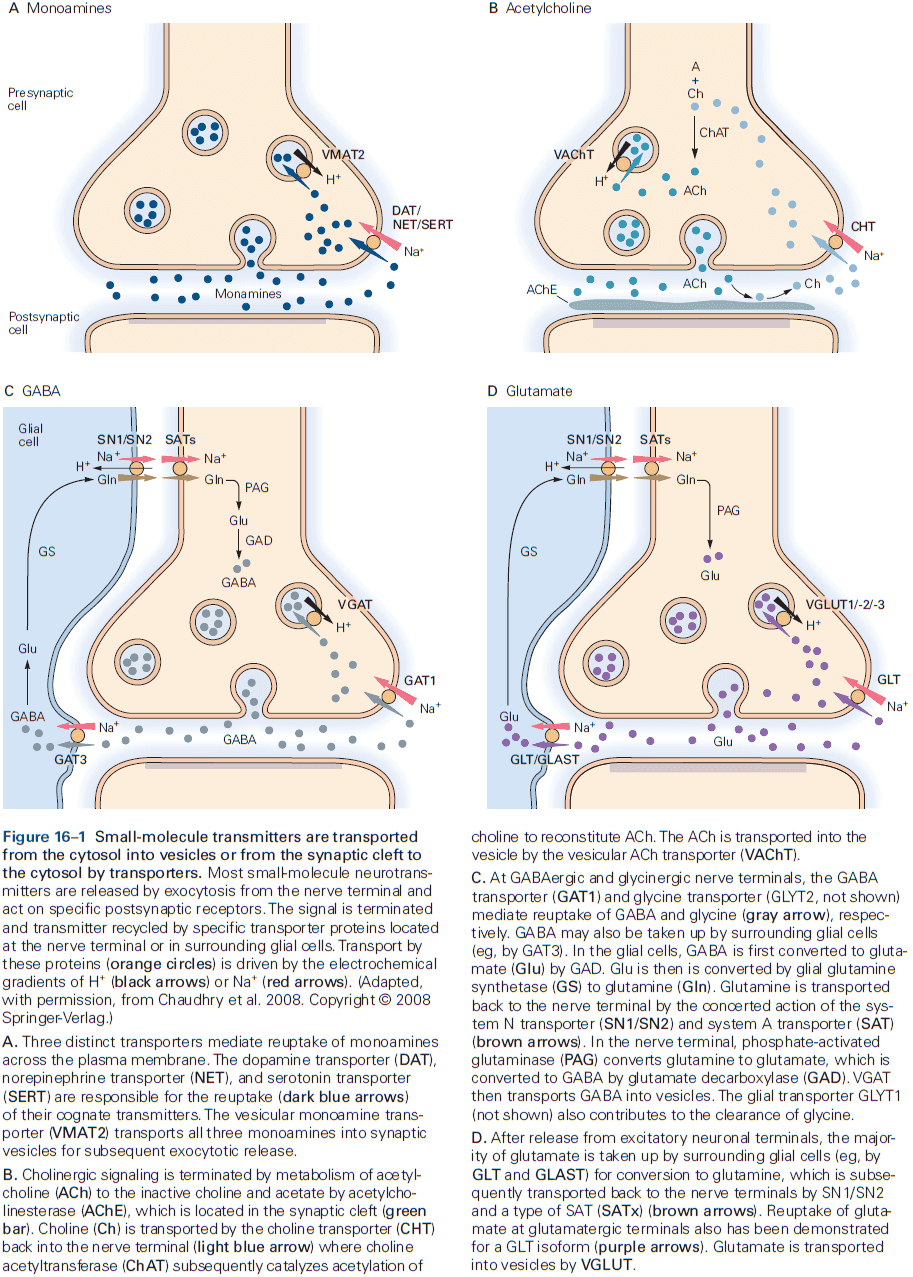

- Review of neurotransmitters, synaptic vesicles, active zones, and exocytosis.

- The released neurotransmitters are the neuron’s output signal and are graded according to the amount of transmitter released, which is controlled by the number and frequency of APs that reach the presynaptic terminals.

- The more the receptor potential exceeds the threshold, the greater the depolarization and the greater the frequency of APs.

- The duration of the input signal also determines the duration of the train of APs.

- The model of neuronal signaling that we’ve outlined is a simplification that applies to most, but not all, neurons.

- E.g. Some neurons don’t generate APs and instead only use graded potentials to release neurotransmitter. Spontaneously active neurons don’t require input to fire APs because they have a special class of ion channels that allows sodium ion flow even in the absence of excitatory synaptic input.

- Neurons can have different ion channel combinations and use different neurotransmitters.

- Because the nervous system has so many cell types and variations at the molecular level, it’s susceptible to more diseases than any other organ in the body.

- Despite this complexity, the molecular mechanisms of electrical signaling are surprisingly similar and aids in the understanding of how signaling occurs since understanding one means understanding all.

- For complex behavior, many neurons are needed but the basic neural structure of the simple reflex is often preserved.

- Basic neural structure of a reflex

- There’s often an identifiable group of neurons whose firing rate changes in response to a particular type of environmental stimulus.

- There’s often an identifiable group of neurons whose firing rate changes before an animal performs a motor action.

- Learning can change behavior that endures for years or even a lifetime, but simple reflexes can also be modified, albeit for a shorter amount of time.

- The fact that behavior can be modified by learning at all raises the question: How can behavior be modified if the nervous system is wired so precisely?

- We don’t have a clear answer, but the most likely solution is the plasticity hypothesis.

- Plasticity hypothesis: the nervous system changes in response to stimuli. Changes can occur at all levels of the nervous system from molecular, pathway, circuit, and regional.

- There’s now considerable evidence for plasticity at chemical synapses.

Highlights

- Neurons are the signaling units of the nervous system. The signals are mainly electrical within the cell and chemical between cells.

- Neurons share common features such as receptors, mechanism to convert input to electrical signals, a threshold mechanism to generate APs, APs, and neurotransmitters.

- Neurons differ in their morphology or shape, the connections they make, and where they make them.

- Glia support neurons such as being the myelin sheath that speeds up APs or by cleaning up used neurotransmitters.

- Neural connections can be modified by experience.

Chapter 4: The Neuroanatomical Bases by Which Neural Circuits Mediate Behavior

- The brain can accomplish complex feats of perception and motion because its neurons are wired together in very precise functional circuits.

- At a gross level, the brain is hierarchically organized such that information processed at one level is passed to higher-level circuits for more complex and refined processing.

- In essence, the brain is a network of networks.

- This chapter explores how neural circuits enable the brain to process sensory input and produce motor output.

- Different circuits in the brain have evolved an organization to most efficiently carry out specific functions.

- Information carried by long pathways, such as the corpus callosum, integrates the output of many local circuits.

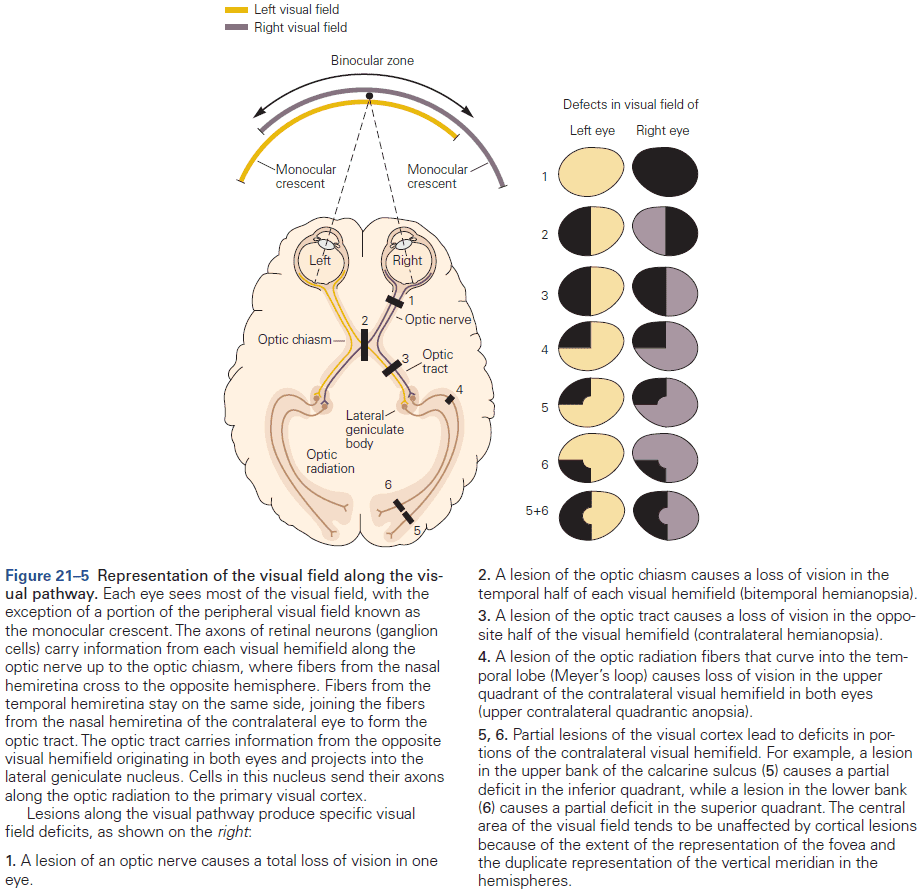

- Different types of information, even within a single sensory modality, are processed in several anatomically discrete pathways.

- E.g. In the somatosensory system, a light touch and a painful pin prick to the same area of skin are mediated by different sensory receptors that connect to distinct pathways.

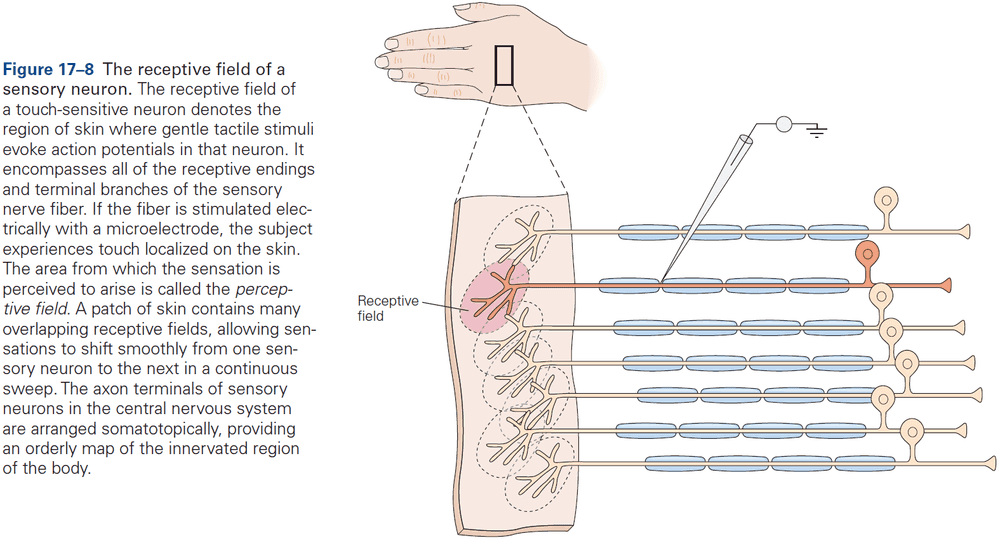

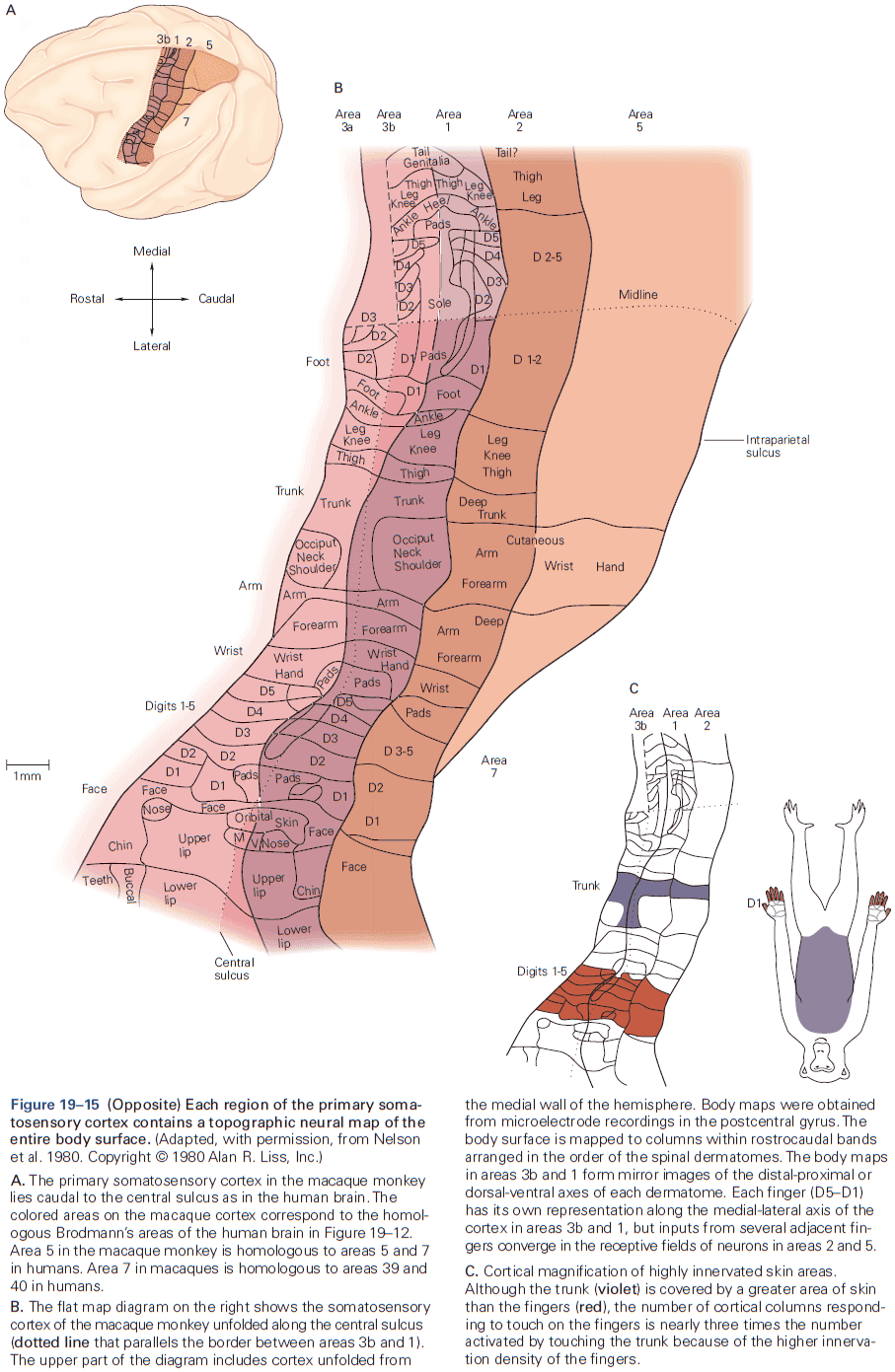

- Fibers that relay information from different parts of the body maintain an orderly relationship to each other and form a map of body surface in their pattern of termination at each synaptic relay.

- This is called a topographical representation since locations that are close on the body are also represented as close in the nervous system.

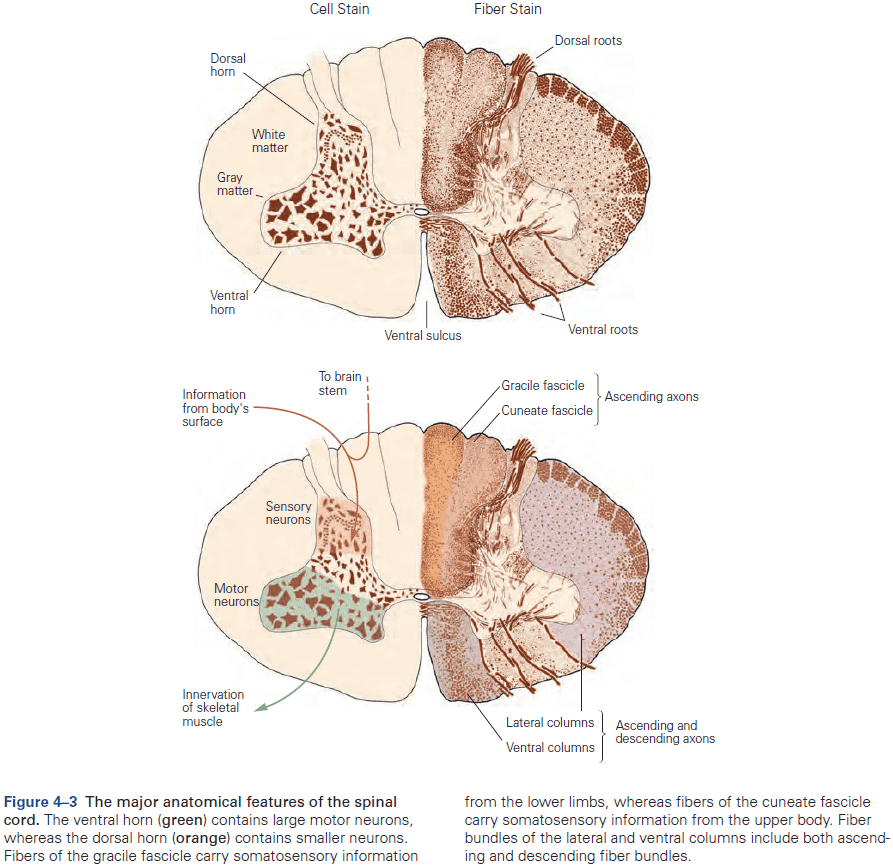

- Review of the spinal cord, four major regions (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral).

- The rostral (head) spinal cord has an increasing proportion of ascending and descending axons, while the caudal (tail) spinal cord has an increasing proportion of gray matter.

- Another organizational feature of the spinal cord is its variation in the size of the ventral and dorsal horns.

- The ventral horn is larger at the levels where the motor nerves innervate the arms and legs, as the number of ventral motor neurons dedicated to a body region roughly parallels the dexterity of movements of that region.

- Similarly, the dorsal horn is larger where sensory nerves from the limbs enter the cord, as limbs have a greater density of sensory receptors to mediate finer tactile discrimination.

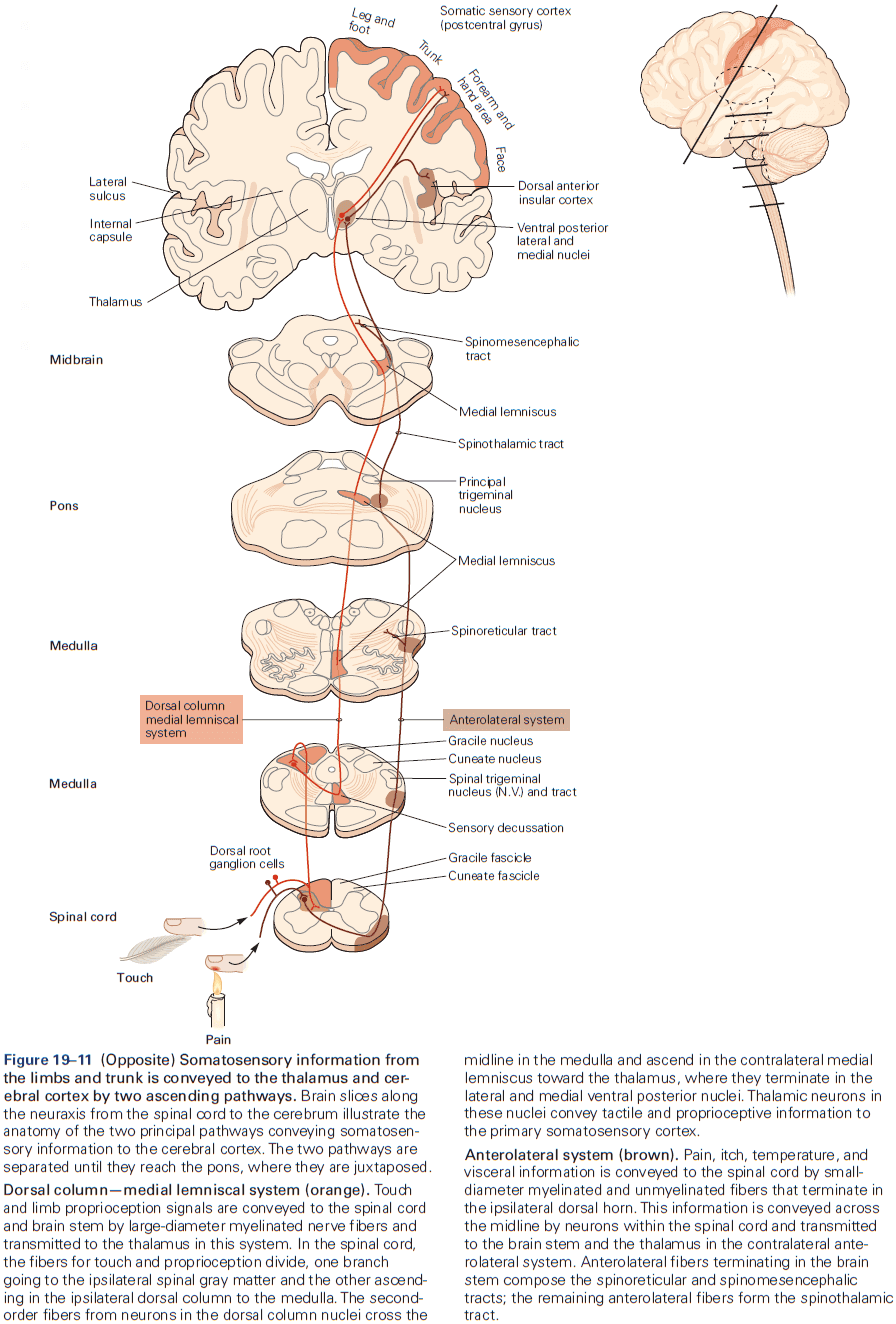

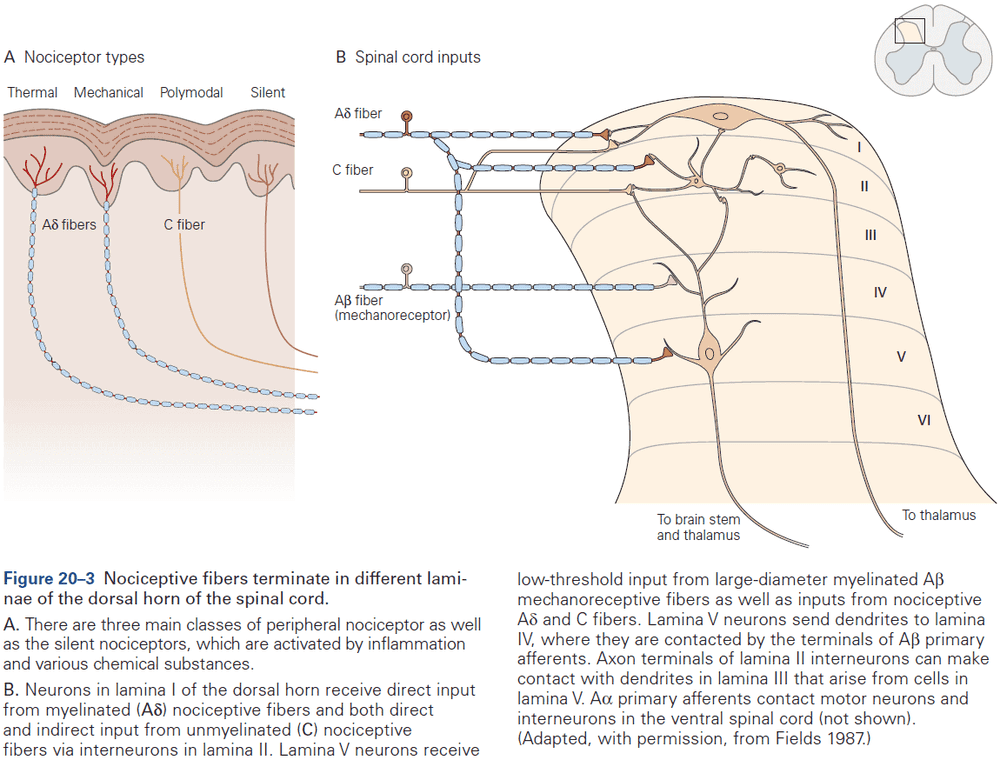

- Two types of somatosensory pathways

- Epicritic: touch and stretch.

- Protopathic: pain and temperature.

- Neurons that make up neural circuits at any particular level are often connected in a systematic way and appear similar from individual to individual.

- E.g. In the cervical cord, axons from all parts of the body have already entered, with sensory fibers from the lower body located medially in the dorsal column, while fibers from the mid and upper body occupying more lateral areas.

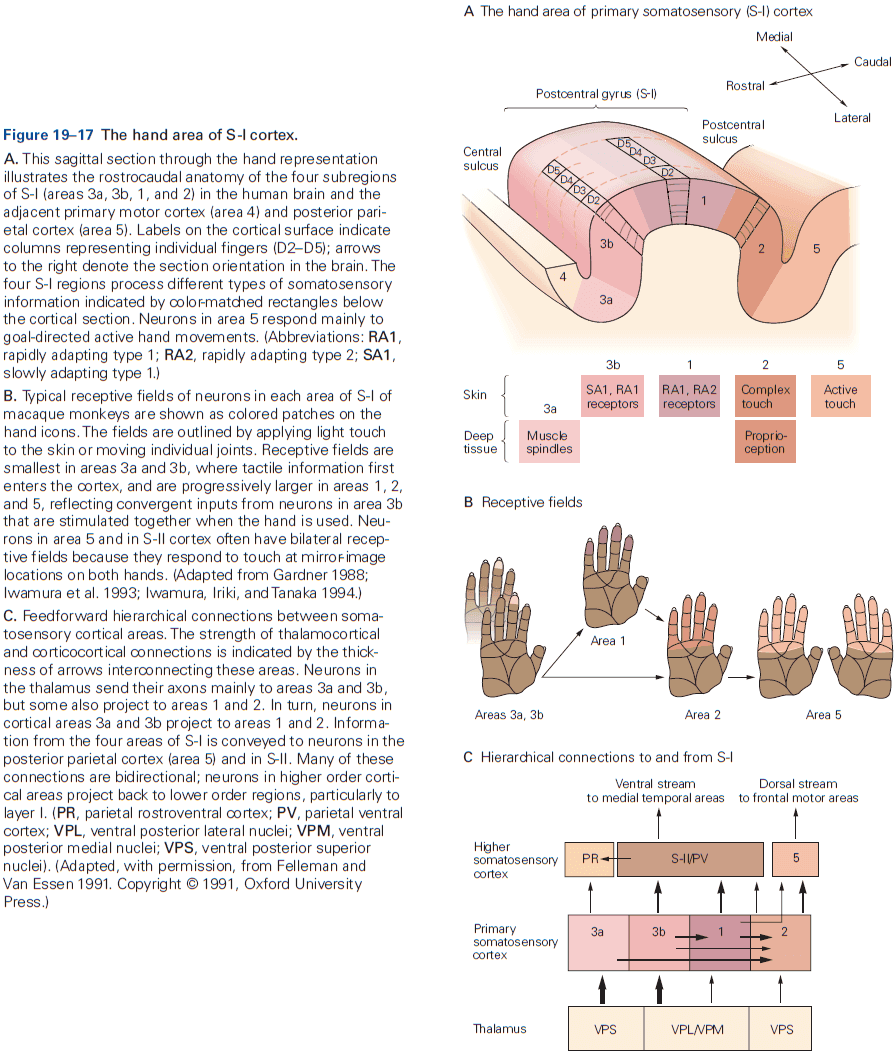

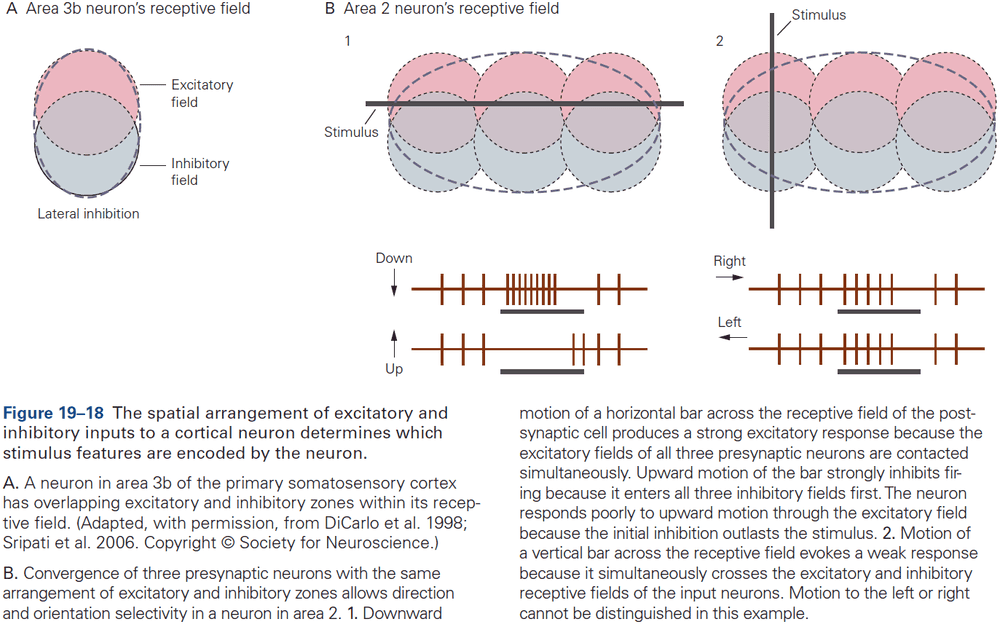

- Each somatic submodality (touch, pain, temperature, and position) are processed in the brain through different pathways that end in different brain regions.

- The thalamus isn’t just a relay, but it acts as a gatekeeper for information to the cerebral cortex, preventing or enhancing the passage of specific information depending on the behavioral state of the organism.

- The cerebral cortex has feedback projections that terminate in a special part of the thalamus called the thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN).

- The TRN forms a thin sheet around the thalamus and is made up almost completely of inhibitory neurons that synapse onto the relay cells. It doesn’t project to the neocortex at all.

- So, the TRN can modulate the response of relay cells to incoming sensory information.

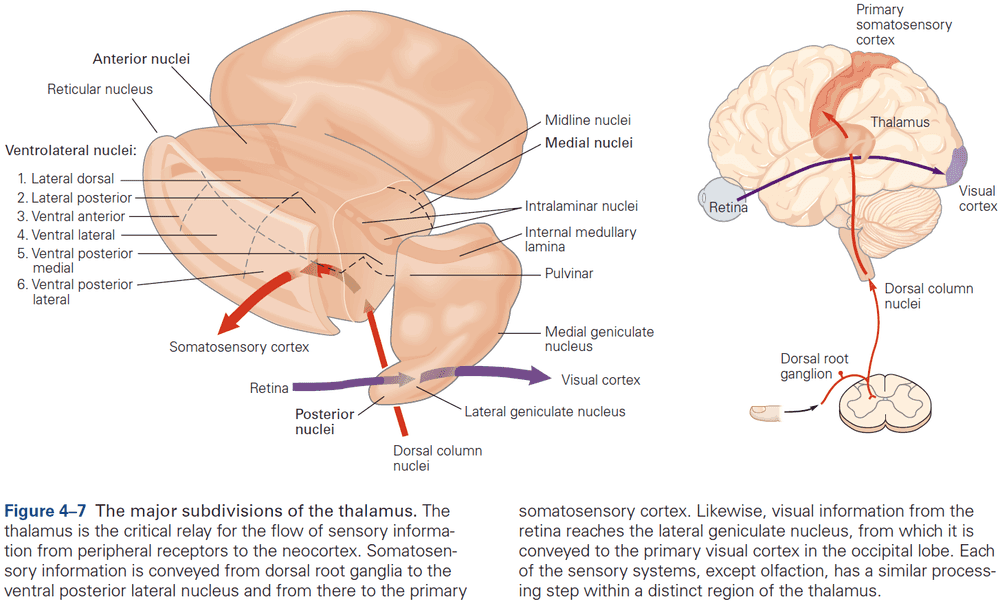

- Four groups of thalamic nuclei

- Anterior

- Connected to the hypothalamus and presubiculum of the hippocampal formation.

- Function is uncertain.

- Medial

- Three subdivisions, each connected to a particular part of the frontal cortex.

- Function in memory and emotional processing.

- Ventrolateral

- Function in motor control, carrying information from the basal ganglia and cerebellum to the motor cortex, carrying somatosensory information to the neocortex, and carrying information from the spinal cord.

- Posterior

- Function in audition (organized tonotopically based on sound frequency) and in vision.

- Anterior

- Most nuclei of the thalamus receive prominent return projections from the cerebral cortex, and the significance of these projections is one of the unsolved mysteries of neuroscience.

- Sensory information processing culminates in the cerebral cortex.

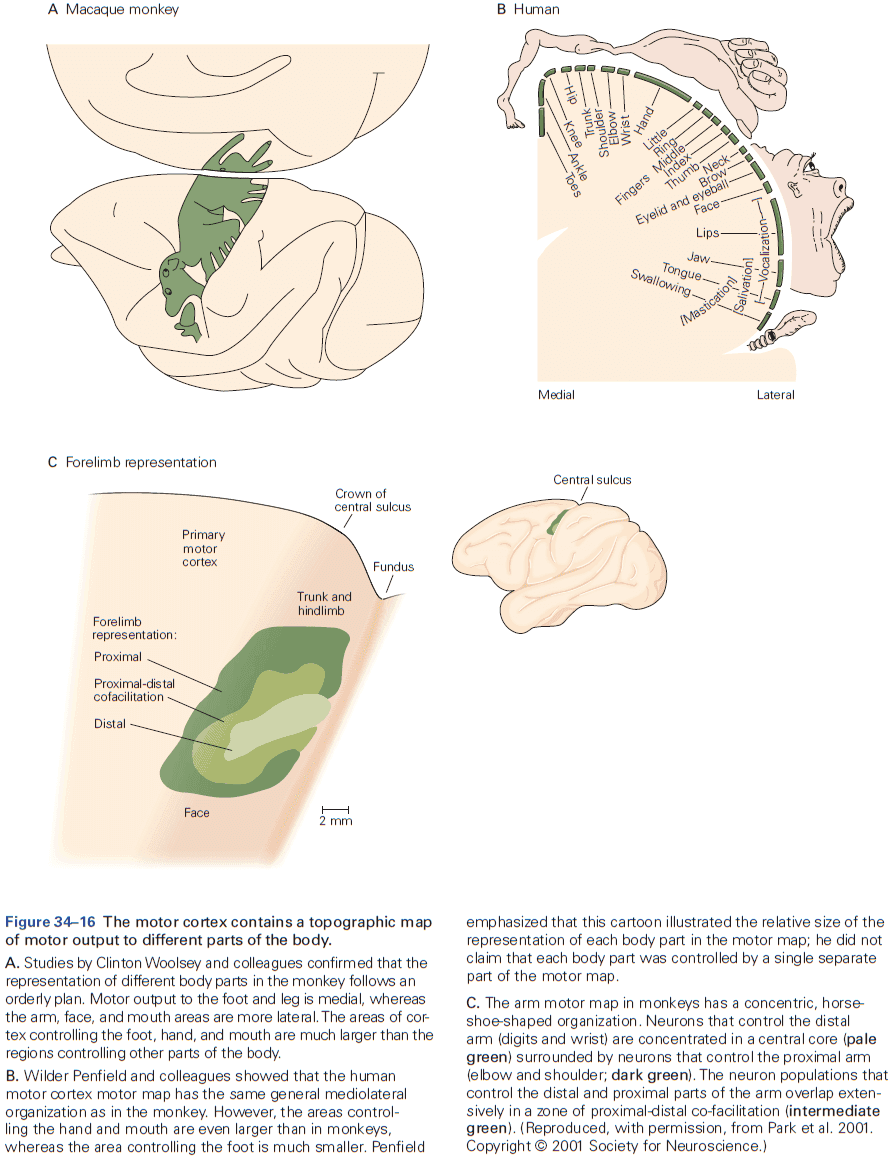

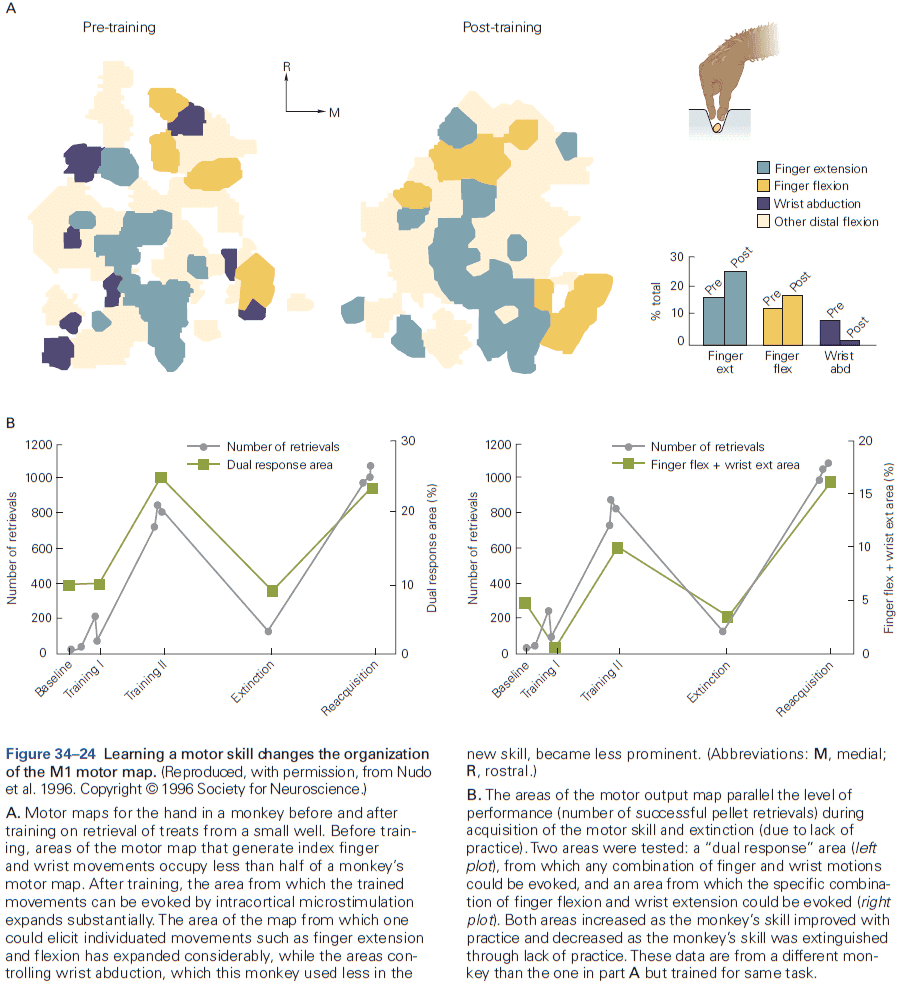

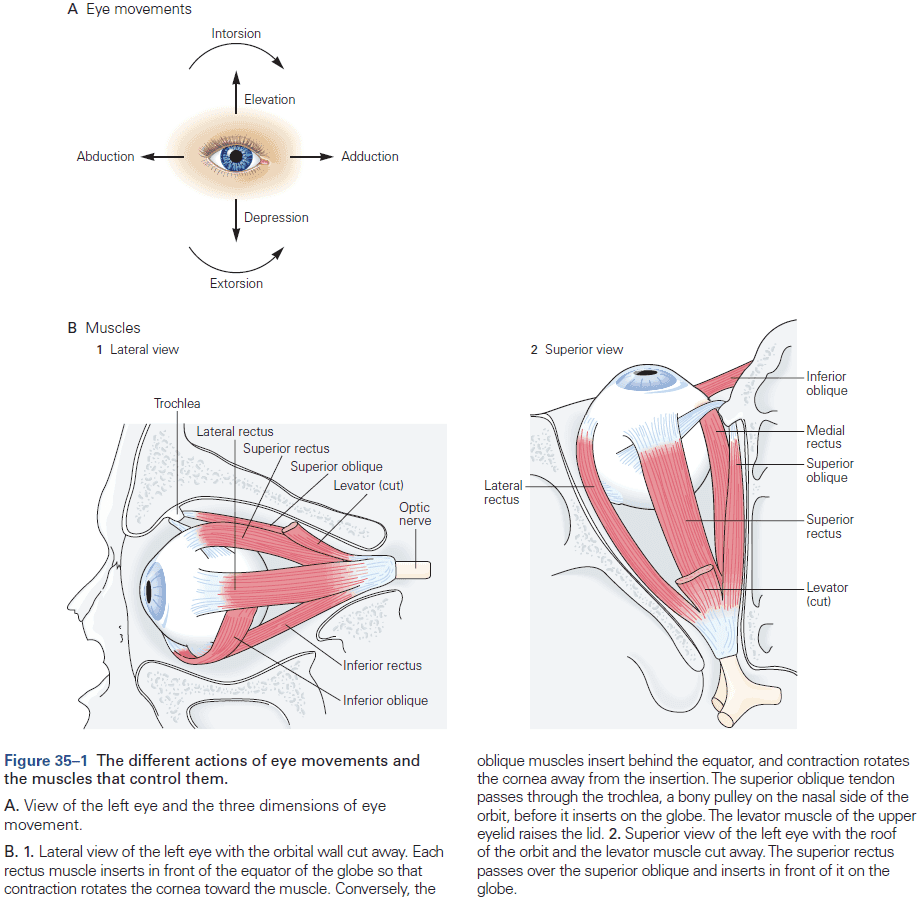

- Review of the sensory and motor homunculus and how those regions can expand/shrink with experience.

- The amount of cortical area dedicated to a part of the body reflects the density of sensory receptors and degree of motor control of that part.

- E.g. Lips and hands occupy more area of the cortex than the elbow.

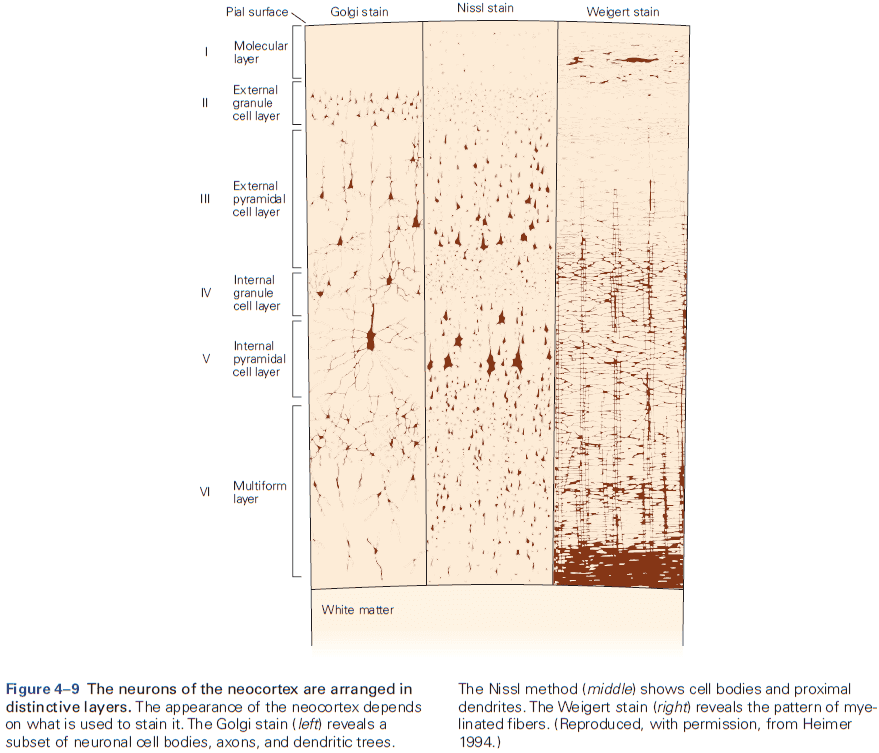

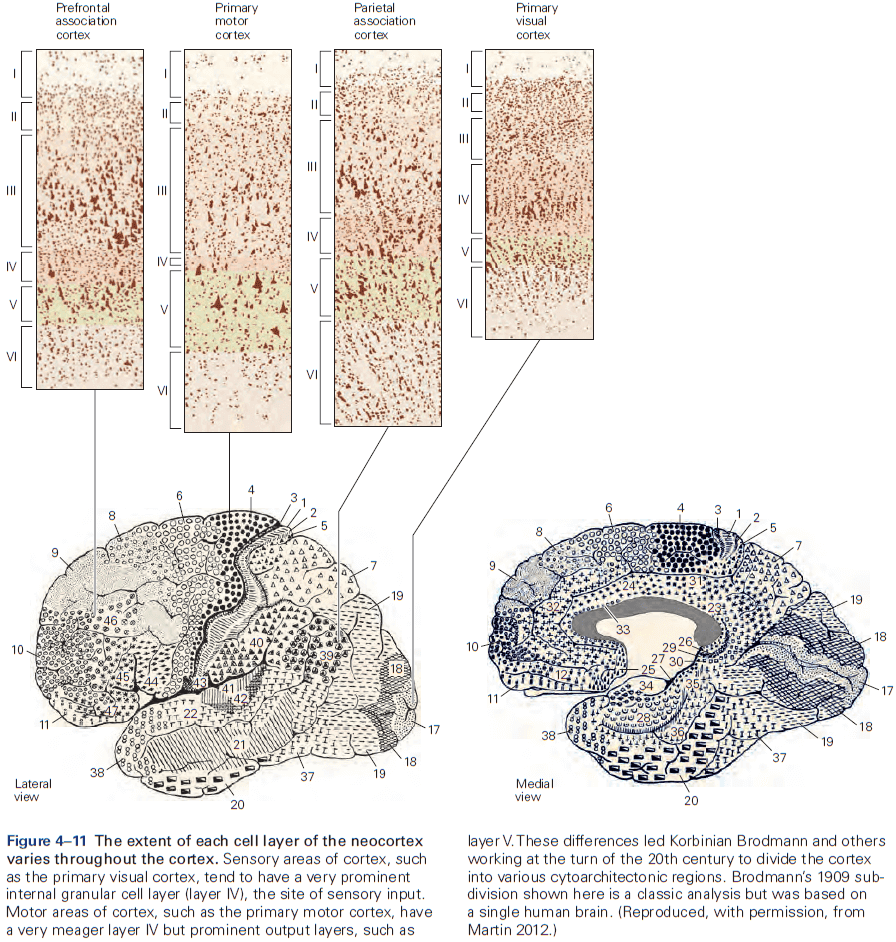

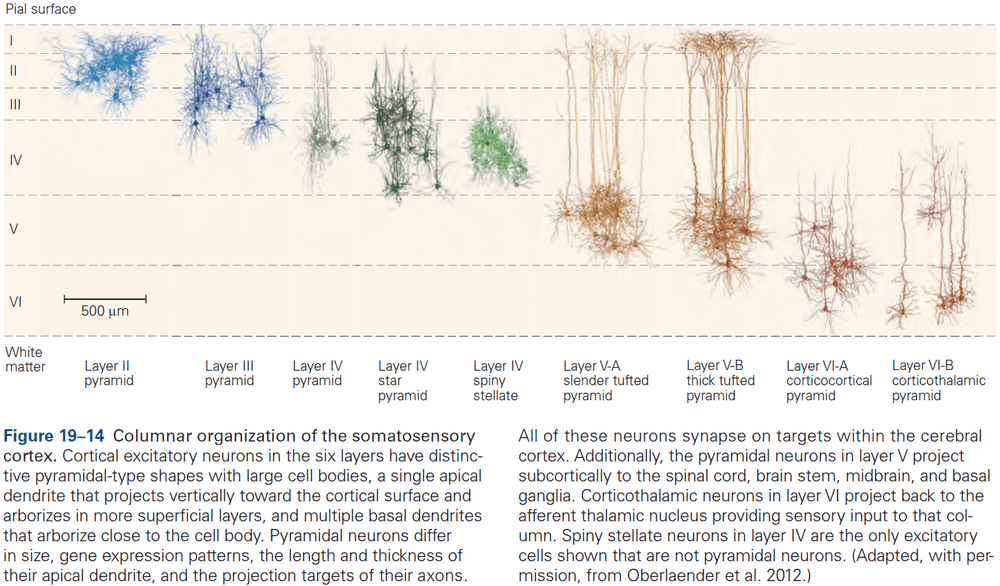

- Six layers of the neocortex

- Layer I (molecular): made up of dendrites from deeper layers and axons that travel through this layer make connections to other cortical areas.

- Layer II (external granule): made up of small spherical neurons and small pyramidal neurons.

- Layer III (external pyramidal): made up of small pyramidal neurons that project locally to other neurons within the same cortical area and to other cortical areas, mediating intracortical communication.

- Layer IV (internal granule): made up of many small spherical neurons and is the main recipient of sensory input from the thalamus. Most prominent in primary sensory areas.

- Layer V (internal pyramidal): made up of many pyramidal neurons that are larger than those in layer III. Gives rise to major output pathways of the cortex, projecting to other cortical areas and to subcortical structures.

- Layer VI (multiform): made up of heterogenous-shaped neurons. Blends into the white matter that forms the deep limit of the cortex and carries axons to and from cortical areas.

- The thickness of individual layers and the details of their functional organization vary throughout the cortex.

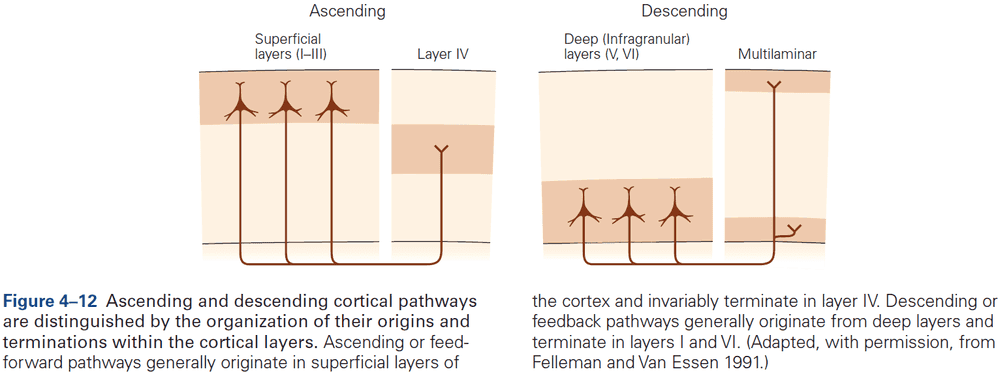

- Within the neocortex, information passes from one synaptic relay to another using feedforward and feedback connections.

- E.g. Feedforward projections from the primary visual cortex to secondary and tertiary visual areas mainly start in layer II and stop in layer IV. In contrast, feedback projections to earlier stages of processing start from layers V and VI and stop in layers I, II, and VI.

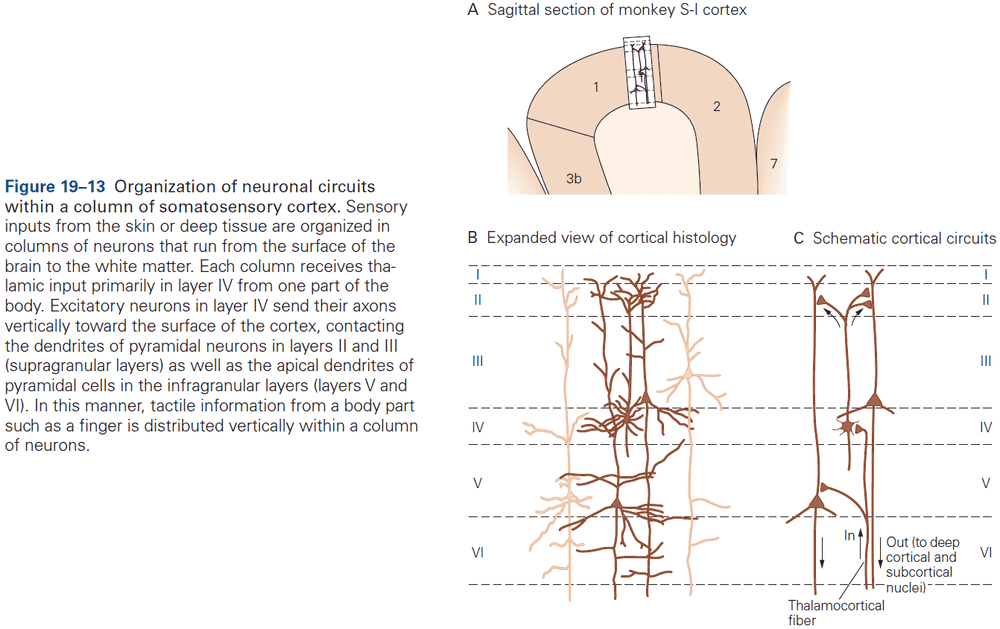

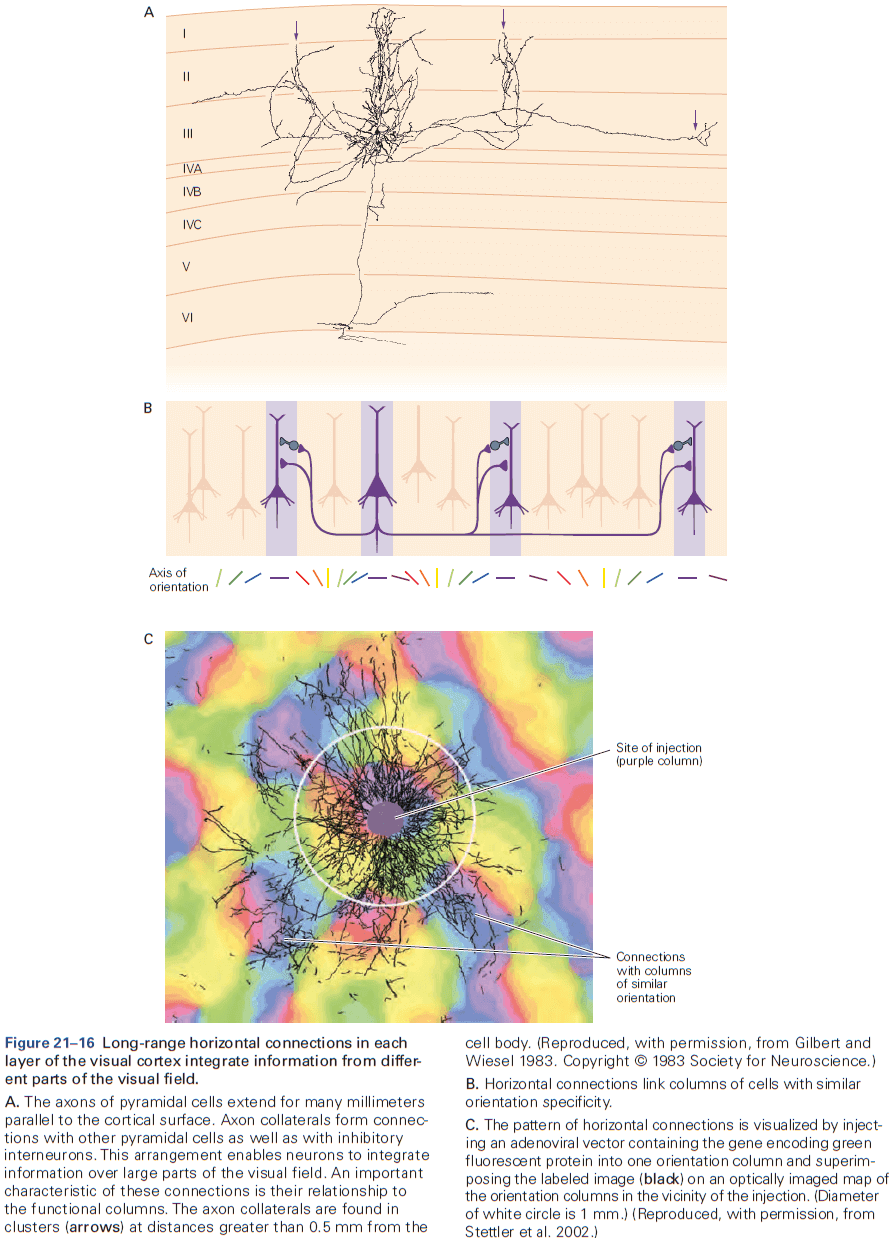

- The cerebral cortex is organized functionally into columns of cells that extend from the white matter to the surface of the cortex, also called cortical columns.

- This columnar organization isn’t particularly evident in standard histological preparations and was first discovered in electrophysiological studies.

- Each column is about one-third of a millimeter in diameter and forms a computational module with a highly specialized function.

- Neurons within a column tend to have very similar response properties and the larger the area of cortex dedicated to a function, the more computational columns it dedicates to that function.

- E.g. The highly discriminative sense of touch in the fingers results from many cortical columns in the large area of cortex dedicated to processing somatosensory information.

- Another important insight about the neocortex is that the somatosensory cortex has not one, but several somatotopic maps of the body surface.

- E.g. The primary somatosensory cortex has four complete maps of the skin.

- The axons from layer V neurons in the primary motor cortex provide the major output of the neocortex to control movement.

- The output may be through direct projections to the corticospinal tract or through indirect projections to the medulla and basal ganglia.

- E.g. Out of the one million corticospinal tract axons, about 40% originate in the motor cortex.

- In the medulla, the fibers from prominent bumps on the ventral surface are called the medullary pyramids, so the entire projection is sometimes called the pyramidal tract.

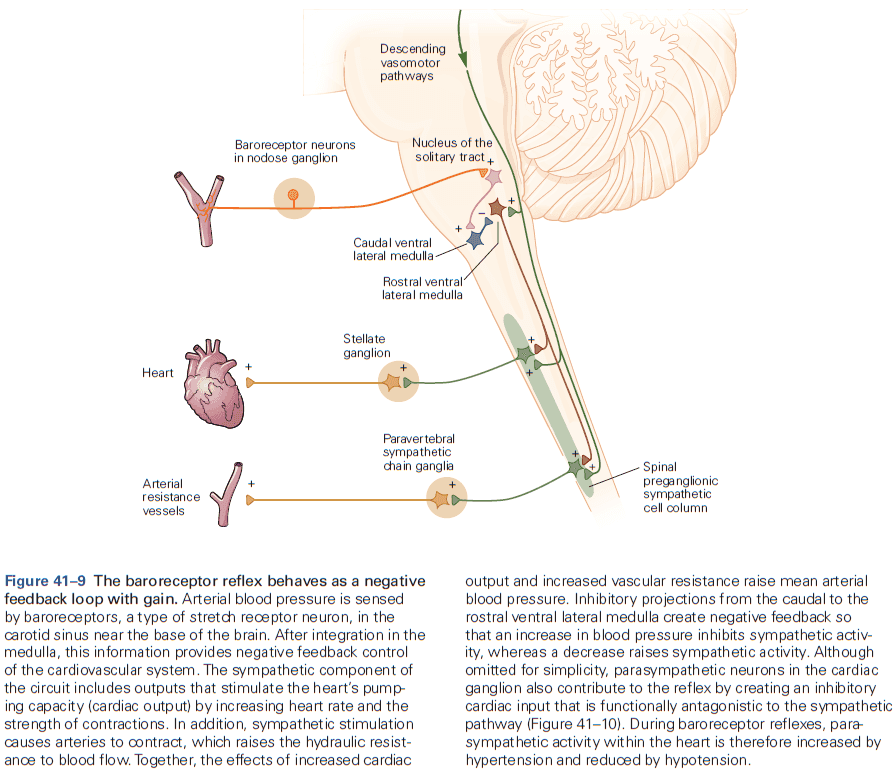

- Review of somatic, autonomic, sympathetic, parasympathetic.

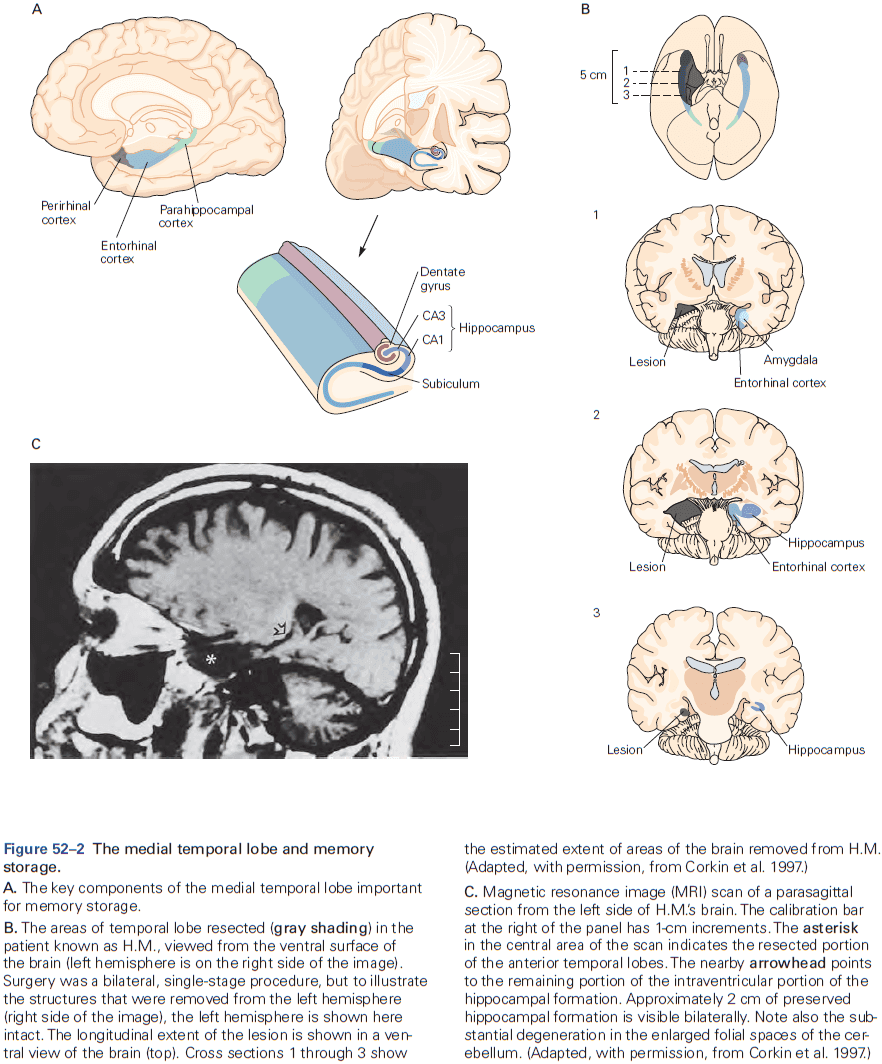

- Memory is a complex behavior mediated by structures distinct from those that carry out sensation or movement.

- Regardless of the behavior, the general principle is that the structure of a circuit is specific to the function that it mediates.

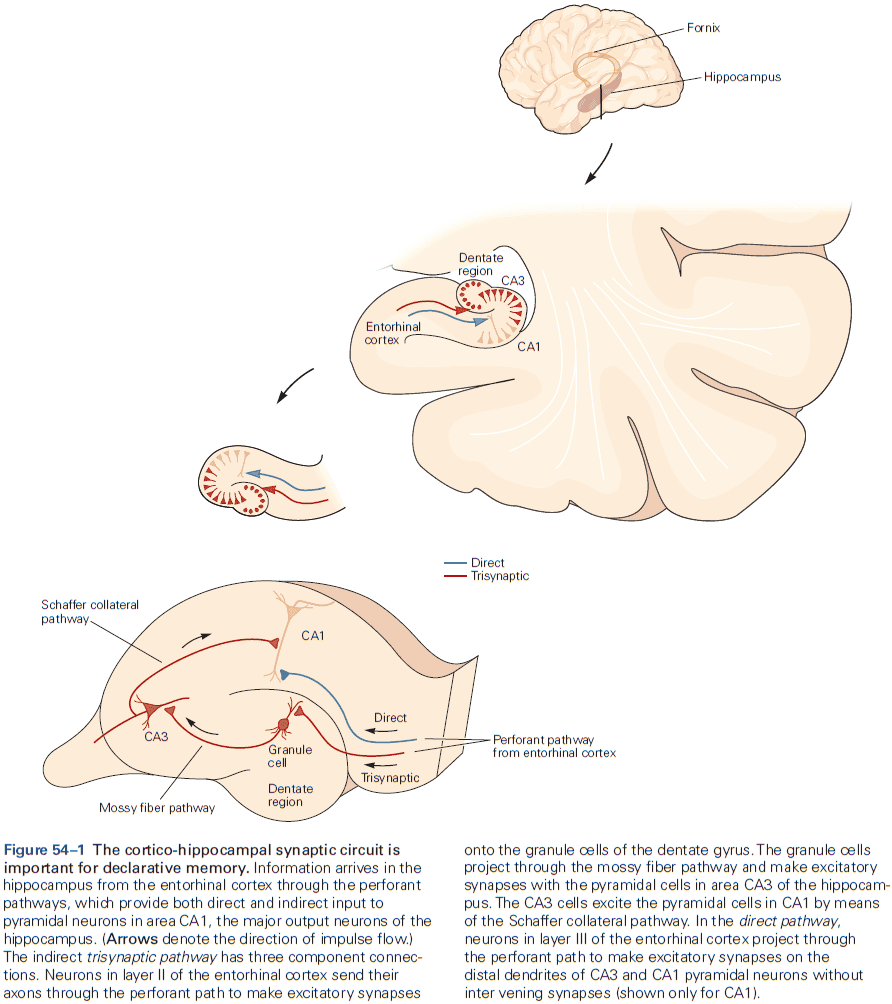

- The hippocampal formation is the structure that mediates memory and mostly consists of unidirectional connections.

- While the hippocampal formation is essential for the initial formation of memories, these memories are ultimately stored elsewhere in the brain.

- E.g. In patient H.M., removal of his hippocampal system left memories prior to the surgery mostly intact.

Highlights

- Individual neurons can’t carry out behavior and they must be part of circuits that comprise of different types of neurons.

- Sensory and motor information is processed separately and in parallel in the brain.

- All sensory and motor systems follow the pattern of hierarchical and reciprocal processing of information, while the hippocampal memory system follow serial processing of very complex, polysensory information.

- A general principle is that circuits in the brain have an organizational structure that’s suited for the functions that they carry out.

- Binding problem: how sensation is integrated into a conscious experience and how conscious experience emerges from the brain’s analysis of incoming sensory information.

Chapter 5: The Computational Bases of Neural Circuits That Mediate Behavior

- This chapter introduces ideas, techniques, and approaches used to characterize and interpret the activity of neural populations and circuits.

- Neural firing patterns provide a code for information on external sensory stimuli and internal muscle movement.

- The structure of a neural representation plays an important role in how information is further processed by the nervous system.

- The sequence of APs fired by a neuron in response to a sensory stimulus represents how that stimulus changes over time.

- Neural coding seeks to understand both the stimulus features that drive a neuron to respond, and the temporal structure of the response and its relationship to changes in the external world.

- Sensory neurons encode information by firing APs in response to sensory features.

- Brain areas must correctly interpret the meaning of AP sequences that they receive from sensory areas to respond properly.

- Decoding: the process of extracting information from neural activity.

- E.g. Recording APs and inferring what the animal or human is seeing or hearing.

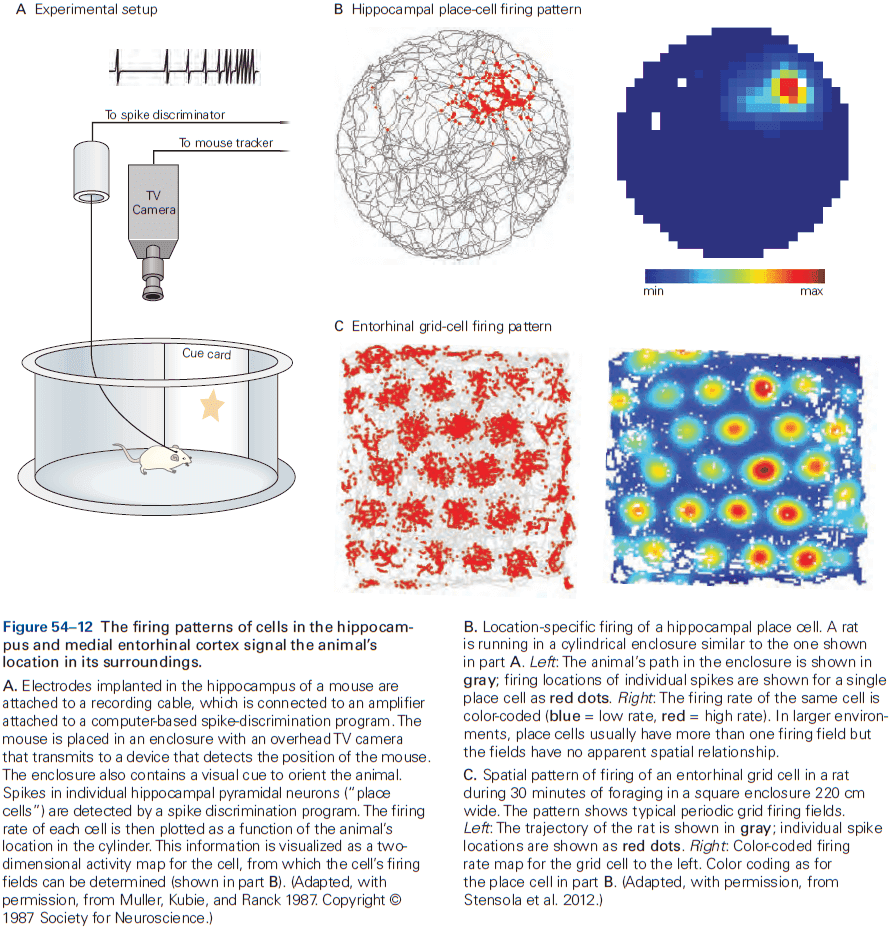

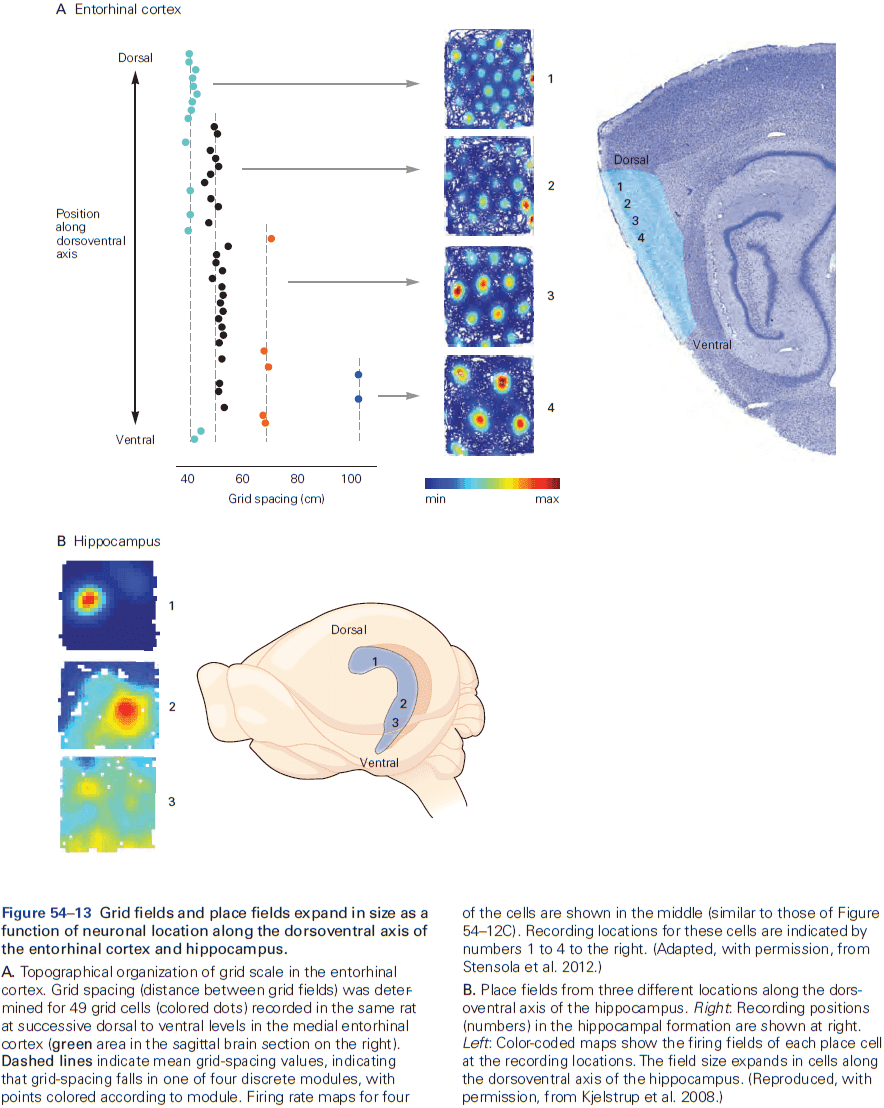

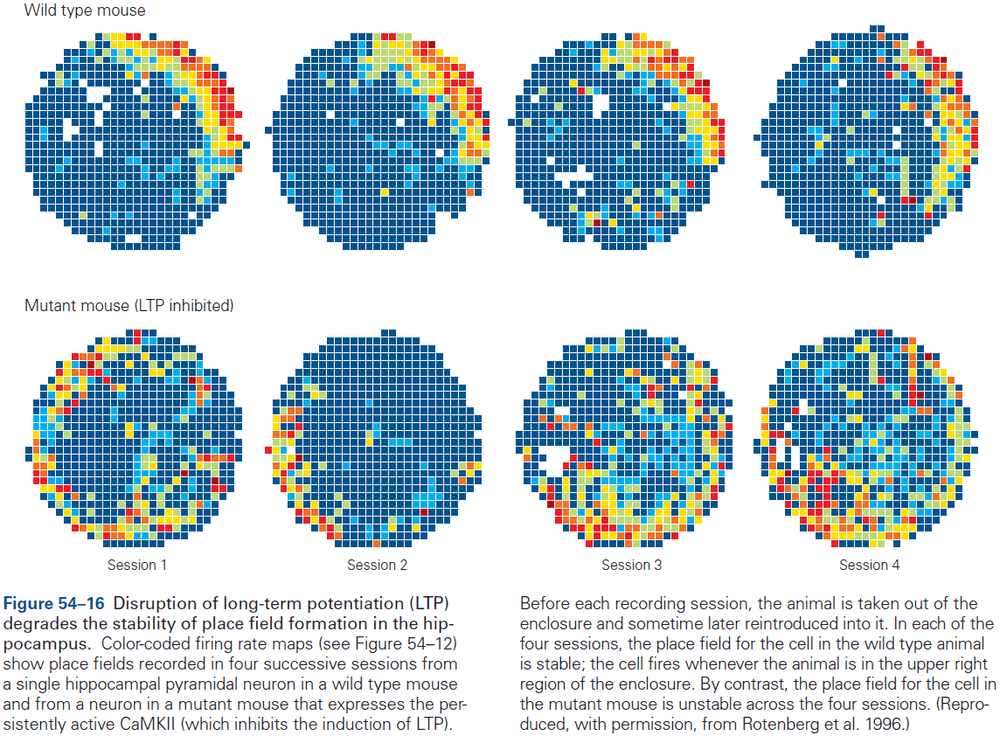

- Review of place and grid cells in the hippocampus.

- During active exploration of an environment, hippocampal activity reflects place coding, but during immobile or resting behavior, the hippocampus enters a different state in which neural activity is instead dominated by discrete semi-synchronous population bursts called sharp-wave ripples.

- It’s hypothesized that these sharp-wave ripples are internally generated by the hippocampus.

- From the lowest to highest stages of visual processing, neurons have increasingly larger receptive fields and higher degrees of selectivity.

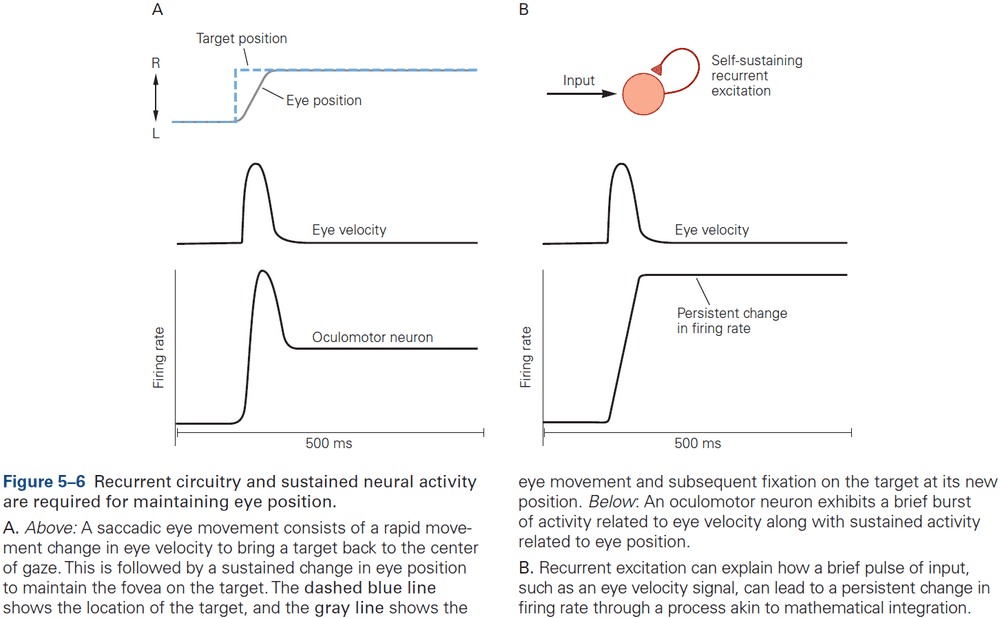

- Recurrent circuitry underlies sustained activity and integration.

- If a neuron’s response decays within a few tens of milliseconds, then how do patterns of neural activity persist long enough to support cognitive operations such as memory or decision making?

- Integration requires both computation and memory to compute and maintain a running total.

- For a neural circuit to perform integration, a transient (short-lived) input must produce activity that’s sustained at a constant level even after the input is gone.

- Thus, the sustained activity provides a memory of the transient input.

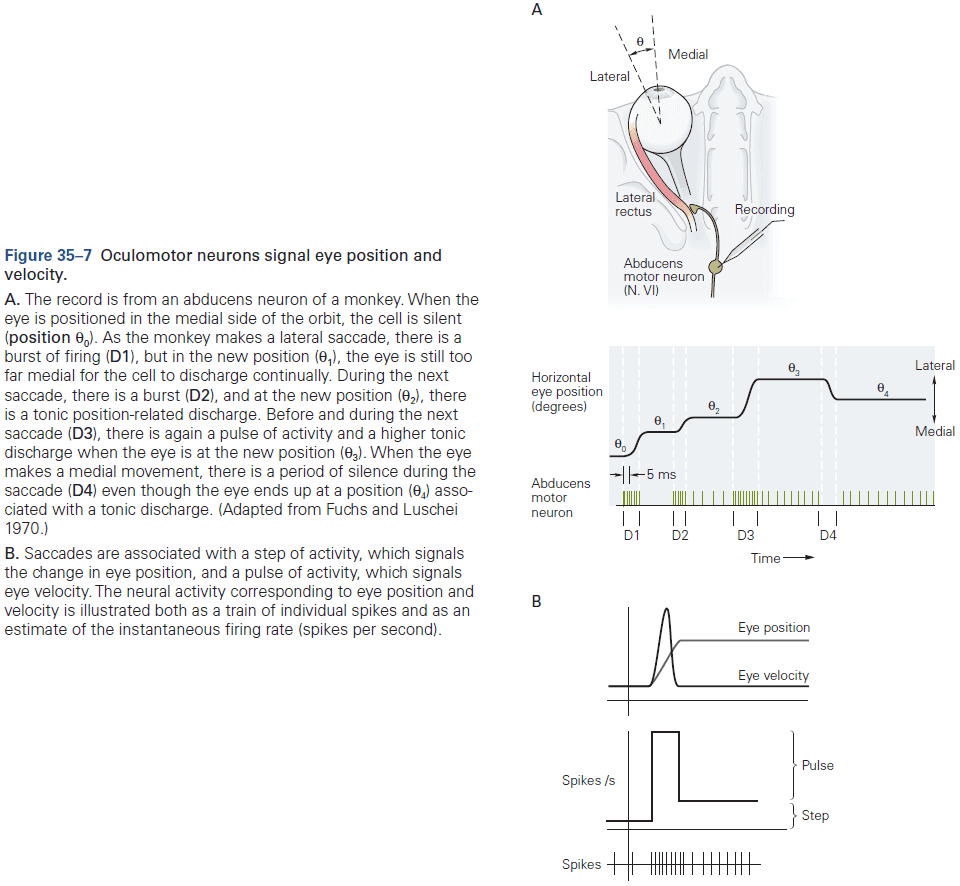

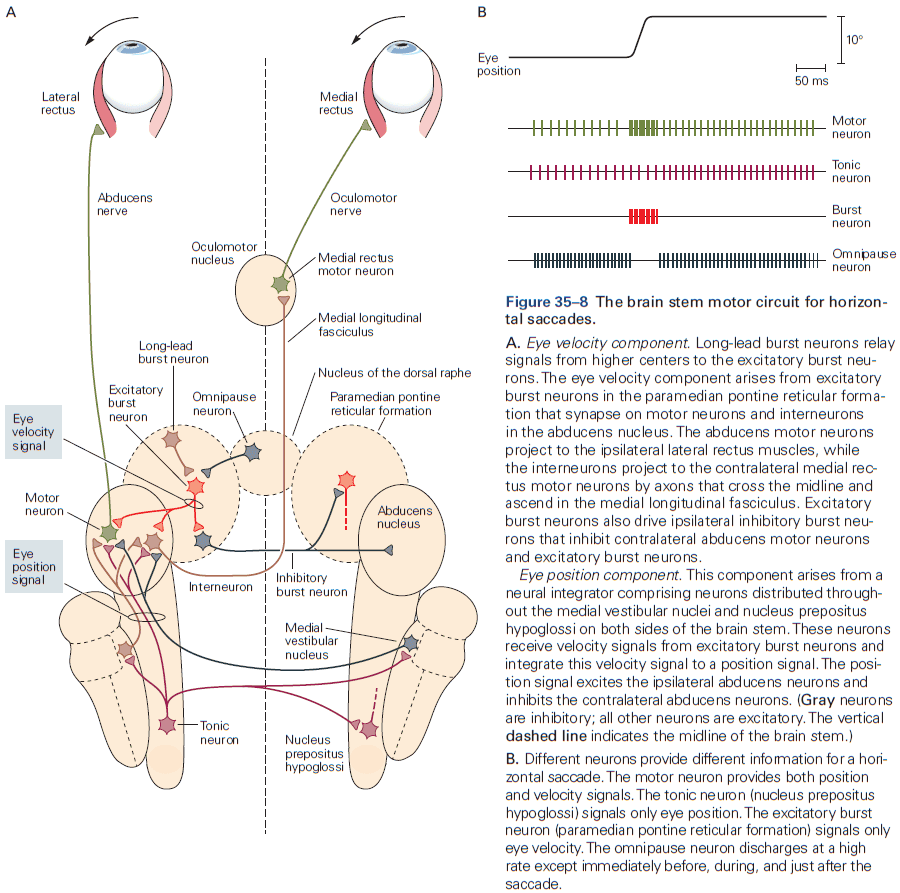

- One of the best studied neural integrators is the circuitry that allows animals to maintain constant gaze direction with their eyes.

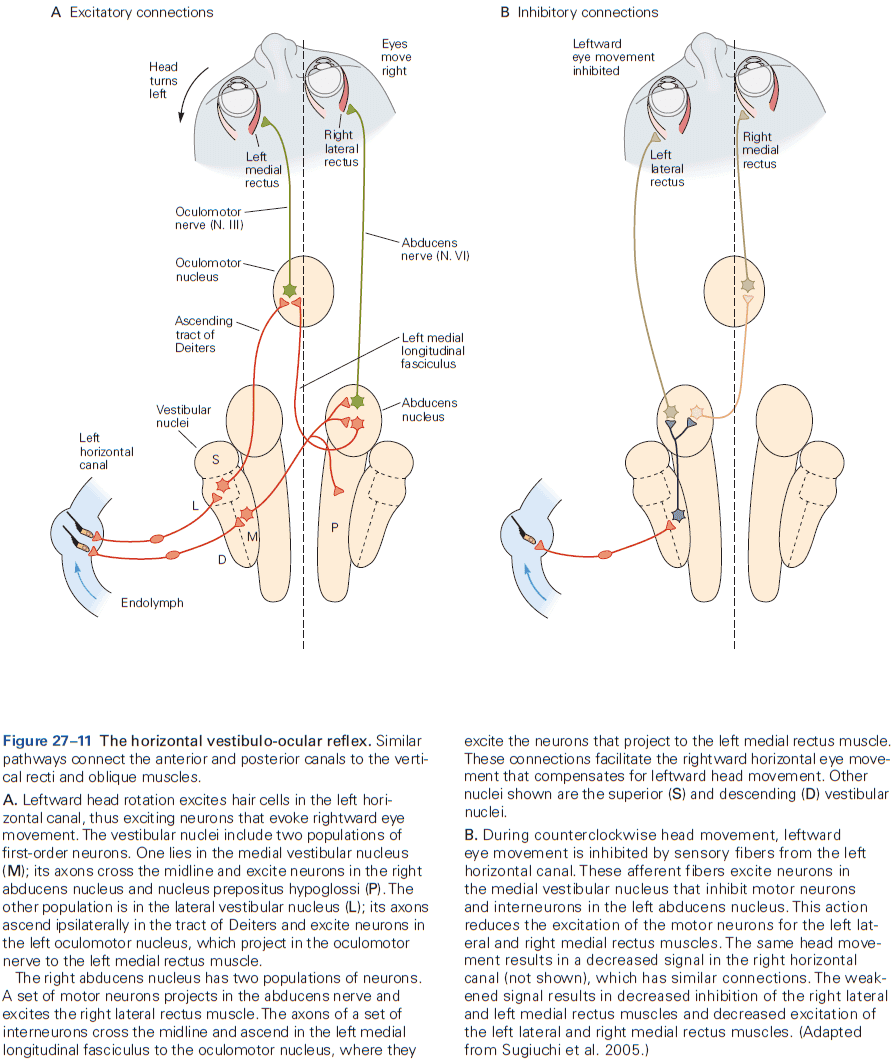

- Lesions or inactivation of the brain stem nuclei medial vestibular nucleus and nucleus prepositus hypoglossi result in a failure to maintain steady horizontal eye position following eye movements, suggesting that the neural integrator circuits lies within these structures.

- How do neural circuits perform integration?

- One possibility is that neurons are wired such that its output is used as an input, a recurrent connection, and if excitation is increased to precisely cancel the decay, then the response can last indefinitely.

- However, eye position in the dark tends to drift back to the center after about 20 seconds, suggesting that the neural integrator isn’t tuned perfectly. If it was, then eye position wouldn’t drift at all.

- In short, although much has been learned about how integration could be implemented, the actual details of the network architecture that support integration remain unknown.

- Experience can modify neural circuits to support memory and learning.

- Multiple forms of plasticity have been identified and each of these presumably supports a different form of learning.

- Review of unsupervised, supervised, reinforcement learning, and Hebbian learning.

- Hebbian plasticity provides a way for neurons to determine and extract the most interesting signal carried by inputs.

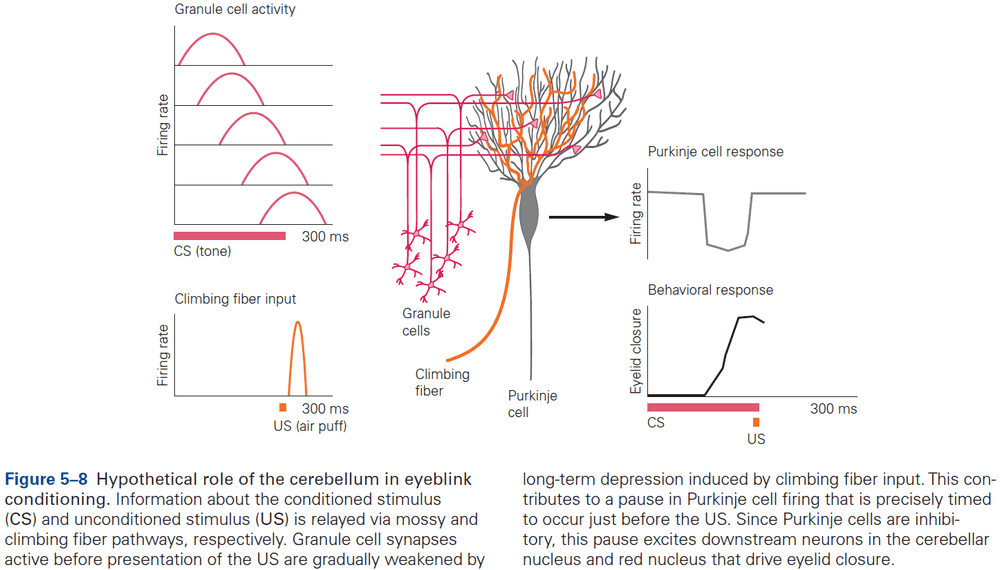

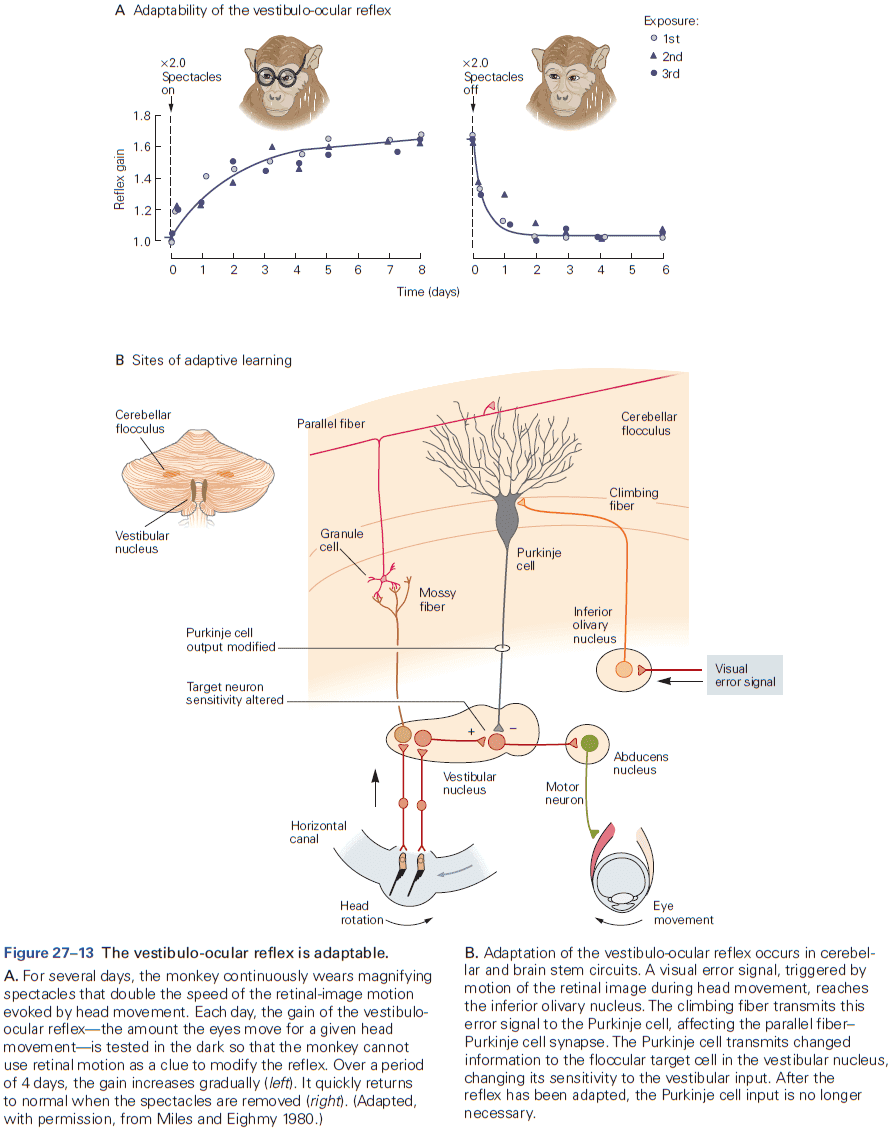

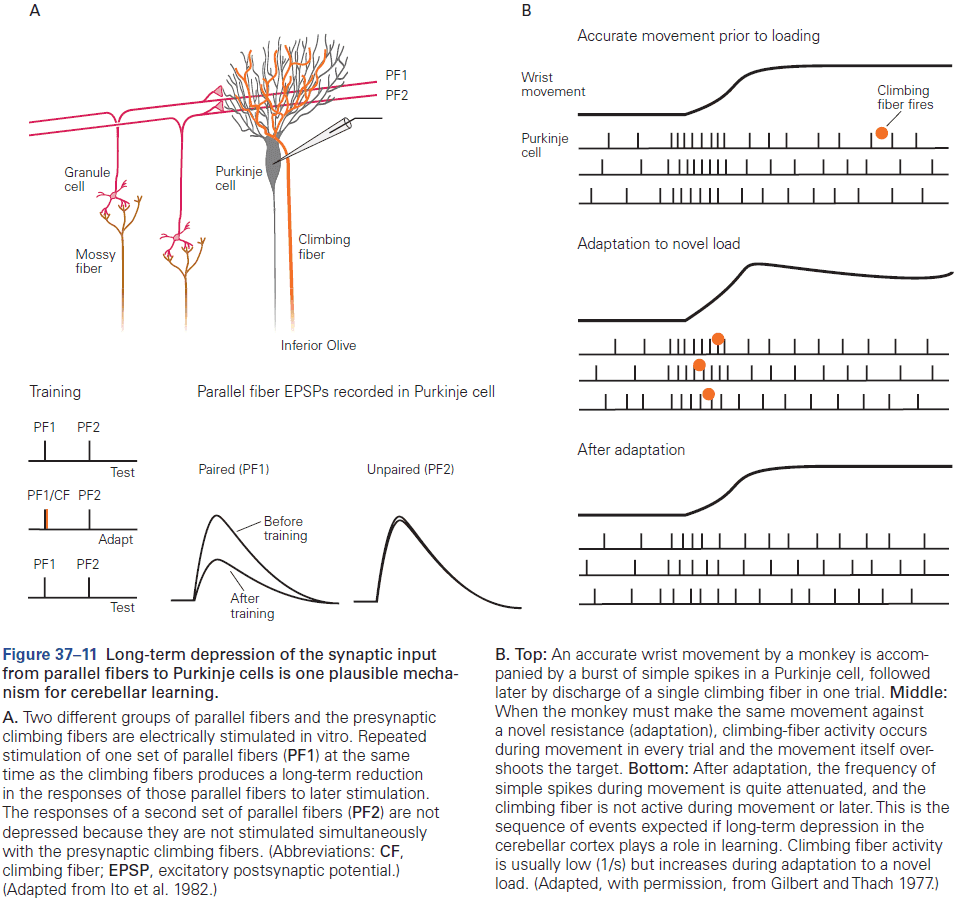

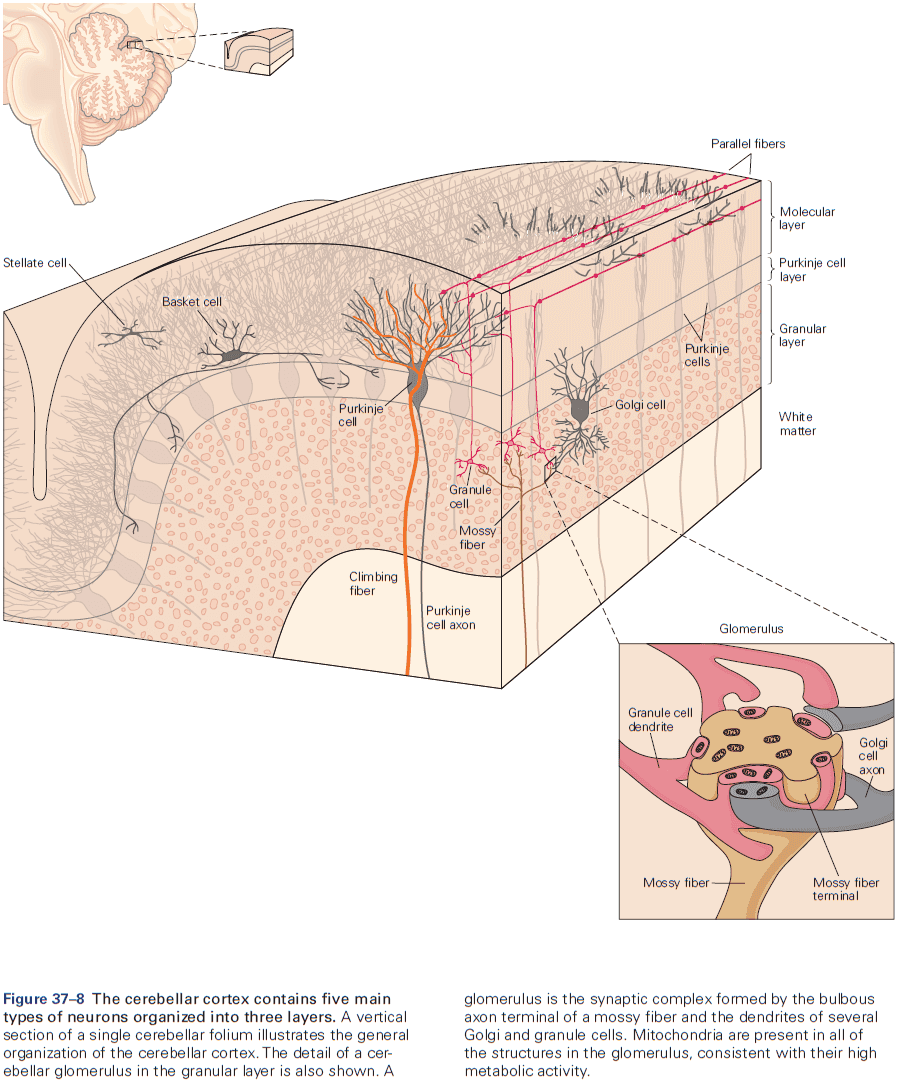

- The eyeblink conditioning paradigm is an example of how synaptic plasticity in the cerebellum plays a key role in motor learning.

- This paradigm provides a concrete example of how neural circuits can mediate learning through trial and error.

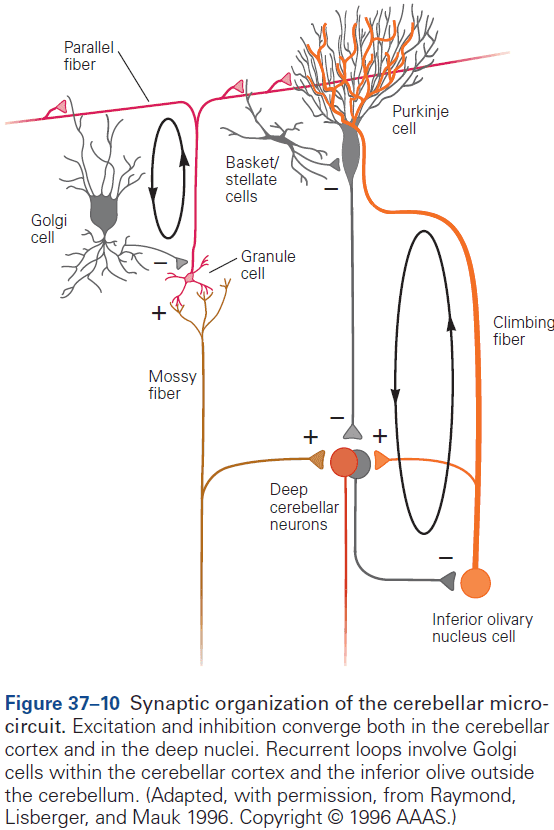

- E.g. Purkinje cells integrate signals related to both the external world and internal state of the animal (conveyed by granule cells), with highly specific information about errors or unexpected events (conveyed by climbing fibers). The climbing fiber acts as a teacher, weakening previously active synapses that could have contributed to errors.

- These changes in synaptic strength alter the firing patterns of Purkinje cells and, by virtue of specific wiring patterns, alter behavior such that errors are gradually reduced.

Highlights

- Neural coding: how stimulus features or actions are represented by neuronal activity.

- Neural circuits are highly interconnected and there are a few basic motifs used to characterize their functions and modes of operation.

- E.g. Feedforward and feedback.

- Levels of neural activity must often be maintained for many seconds to minutes. One mechanism is networks of recurrent excitation.

- Synaptic plasticity supports longer-lasting changes in neural circuits that underlie learning and memory.

- E.g. Hebbian plasticity can extract interesting signals without the need for supervision/teacher.

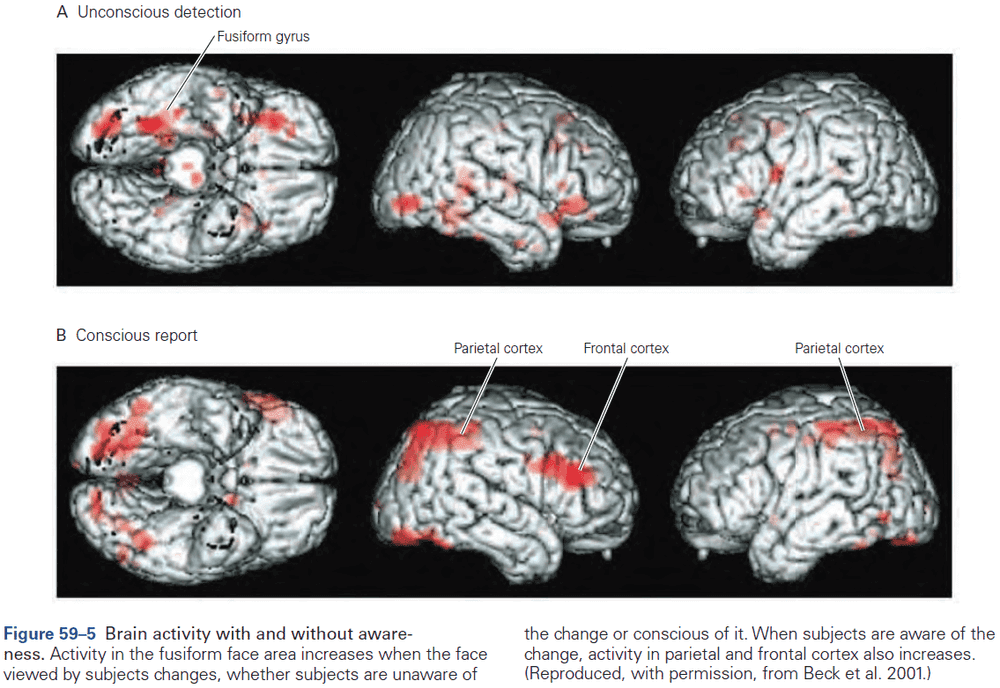

Chapter 6: Imaging and Behavior

- This chapter focuses on fMRI.

- Benefits of using fMRI

- Non-invasive.

- Can measure brain function over short periods of time (seconds).

- Measures activity across the whole brain simultaneously.

- fMRI experiments measure neurovascular activity, specifically changes in local blood oxygen levels that occur in response to neural activity.

- Review of the physics of MRI and the BOLD signal.

- Drawbacks of using fMRI

- Unclear whether BOLD is more closely tied to the firing of individual neurons or populations of neurons.

- Difficult to distinguish whether increased blood oxygenation is caused by increases in local excitation or inhibition.

- The mechanisms of neurovascular coupling, how the brain knows when and where to deliver oxygenated blood, remains mysterious.

- fMRI has utility as a tool to localize changes in neural activity in the human brain induced by mental operations.

- Five basic fMRI preprocessing steps

- Motion correction: addresses head movements causing misaligned data.

- Slice-time correction: addresses differences in timing of the acquisition of samples across different slices.

- Temporal filtering: removes components of the time course that are highly likely to be noise.

- Spatial smoothing: applies a kernel to blur individual volumes, averaging out noise and improving alignment.

- Anatomical alignment: registers data across runs and subjects to a structural scan and then a standard template such as the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) or Talairach space.

- Three insights gained from fMRI studies

- Have inspired neurophysiological studies in animals such as the location of face processing.

- Have challenged theories from cognitive psychology and systems neuroscience such as the location of memory and the role of the hippocampus.

- Have tested predictions from animal studies and computational models such as reinforcement learning models.

Highlights

- Functional brain imaging seeks to record activity in the human brain associated with mental processes as they unfold.

- The link between BOLD activity and behavior is inferred through a series of preprocessing steps and statistical analyses.

- This has led to fundamental insights about how the human brain processes faces, how memories are stored and retrieved, and how we learn from trial and error. Across these domains, data from fMRI have converged with neuronal recordings and theoretical predictions.

- fMRI records brain activity but doesn’t directly modify activity. So it doesn’t support inferences about whether a region is necessary for a behavior, but rather whether the region is involved in that behavior.

Part II: Cell and Molecular Biology of Cells of the Nervous System

- In all biological systems, the basic building block is the cell.

- Complex biological systems have another basic feature: they are architectonic meaning their anatomy, structure, and dynamic properties all reflect a specific physiological function.

- Four key features of neurons

- Polarized. This restricts the flow of voltage impulses to one direction.

- Electrically excitable. Its cell membrane contains specialized proteins, ion channels and receptors, that allow for the movement of ions, thus creating electrical currents that generate voltage across the membrane.

- Neurotransmitters and synapse machinery.

- Cytoskeletal structure. Enables the efficient transport of various proteins, mRNAs, and organelles between compartments.

Chapter 7: The Cells of the Nervous System

- Neurons and glia share many characteristics with cells in general.

- However, neurons are special in their ability to communicate precisely and rapidly with other cells at distant sites in the body.

- Two unique features of neurons

- High degree of morphological and functional asymmetry. This arrangement is the structural basis for unidirectional neuronal signaling.

- E.g. Dendrites and axon.

- Both electrically and chemically excitable.

- E.g. Ion channels and receptors.

- High degree of morphological and functional asymmetry. This arrangement is the structural basis for unidirectional neuronal signaling.

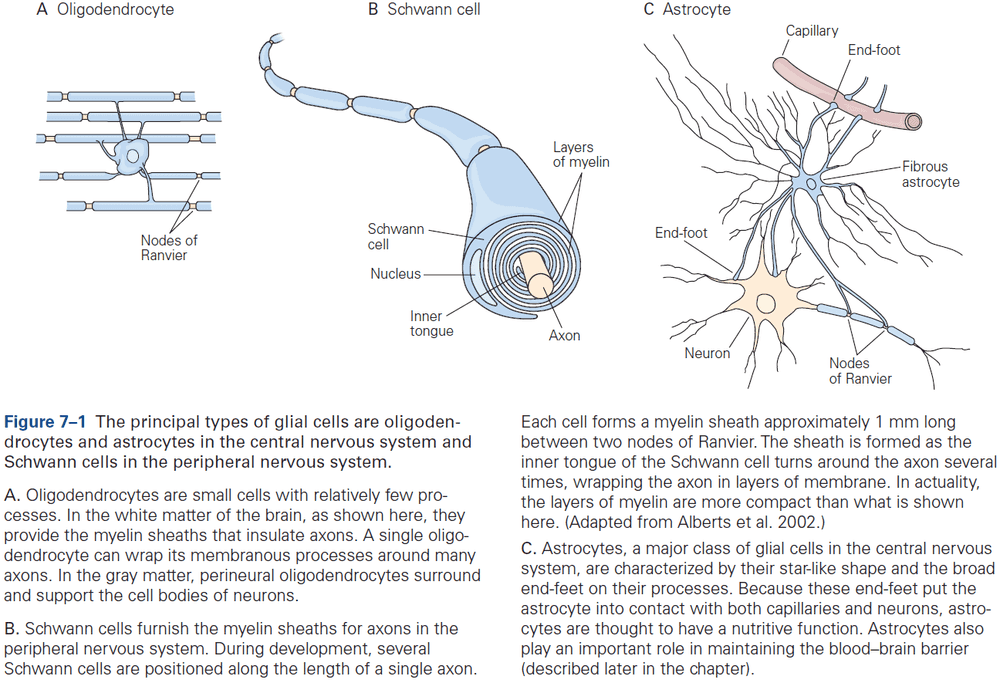

- Two classes of glia

- Macroglia

- E.g. Oligodendrocytes, Schwann cells, and astrocytes.

- Microglia: the brain’s resident immune cells and phagocytes.

- Macroglia

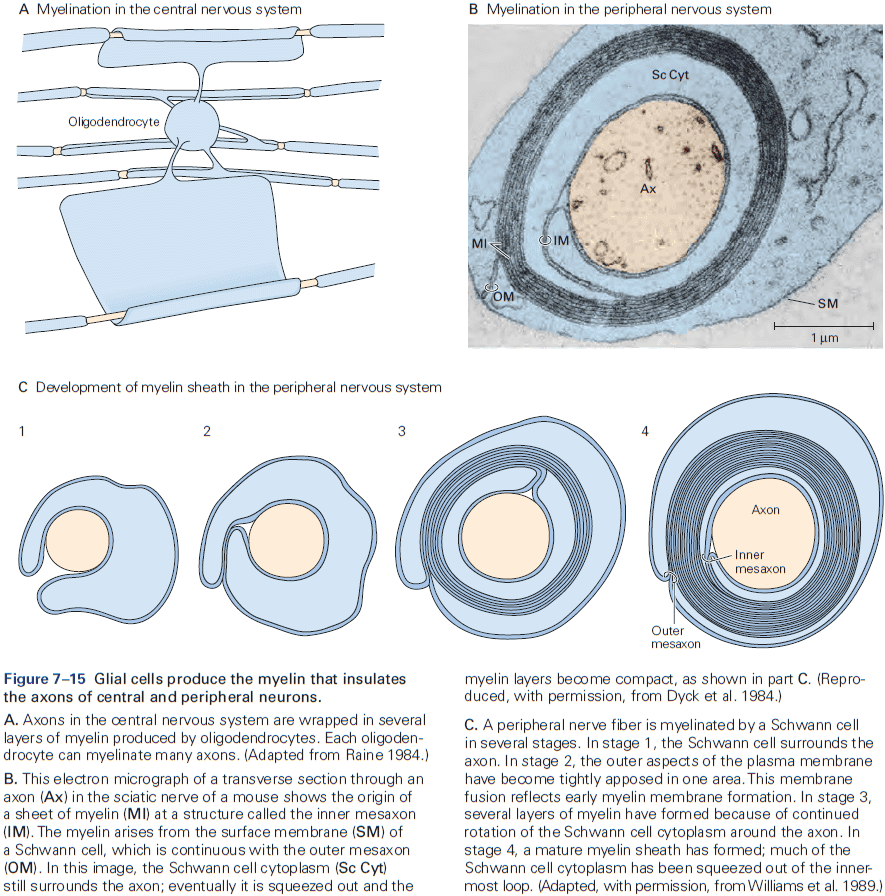

- In the human brain, about 90% of all glial cells are macroglia. Of that 90%, about half of glia are myelin-producing cells (oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells) and half are astrocytes.

- Oligodendrocytes provide the insulating myelin sheath of axon in the CNS, while Schwann cells myelinate the axons in the PNS.

- Nonmyelinating Schwann cells promote, develop, maintain, and repair the neuromuscular synapse, while astrocytes support neurons and modulate neuronal signaling.

- Neurons and glia develop from common neuroepithelial progenitors and share many structural characteristics.

- Skimming over the organelles of a neuron.

- In contrast to the continuity of the cell body and dendrites, a sharp functional boundary exists between the cell body and the axon called the axon hillock.

- The organelles that make the main machinery for proteins in the neuron are generally excluded from axons.

- E.g. Ribosomes, rough endoplasmic reticulum, and the Golgi complexes.

- However, axons are rich in smooth endoplasmic reticulum, synaptic vesicles, and their precursor membranes.

- A cell’s cytoskeleton determines its shape and is responsible for the asymmetric distribution of organelles within the cytoplasm.

- Three parts of the cytoskeleton

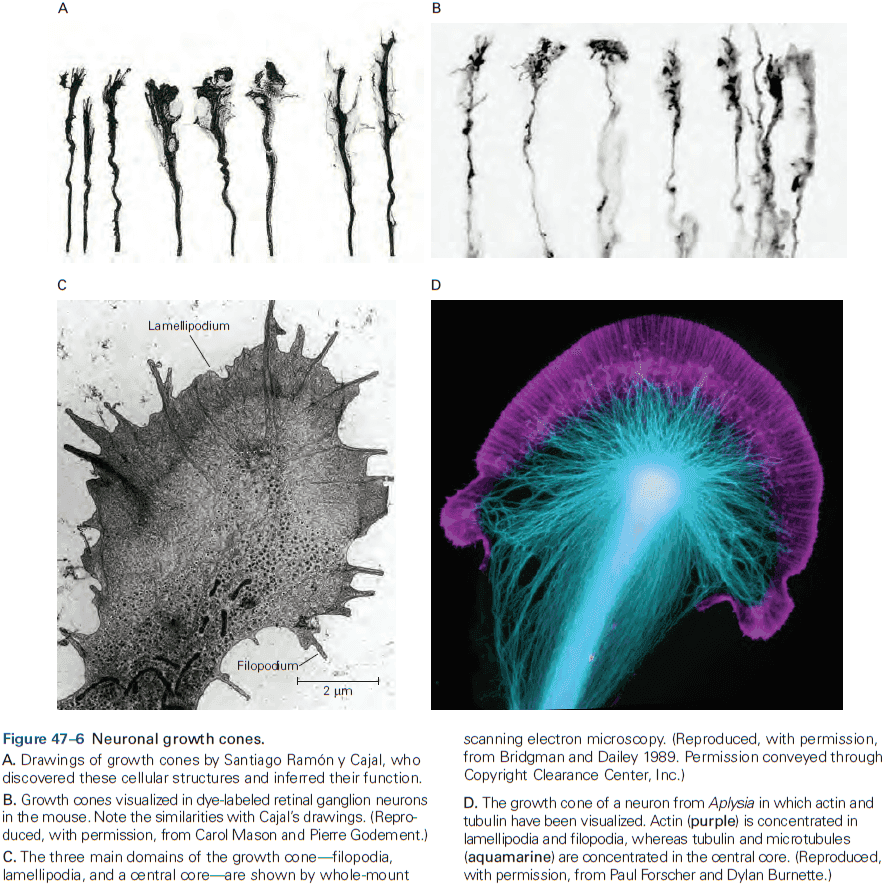

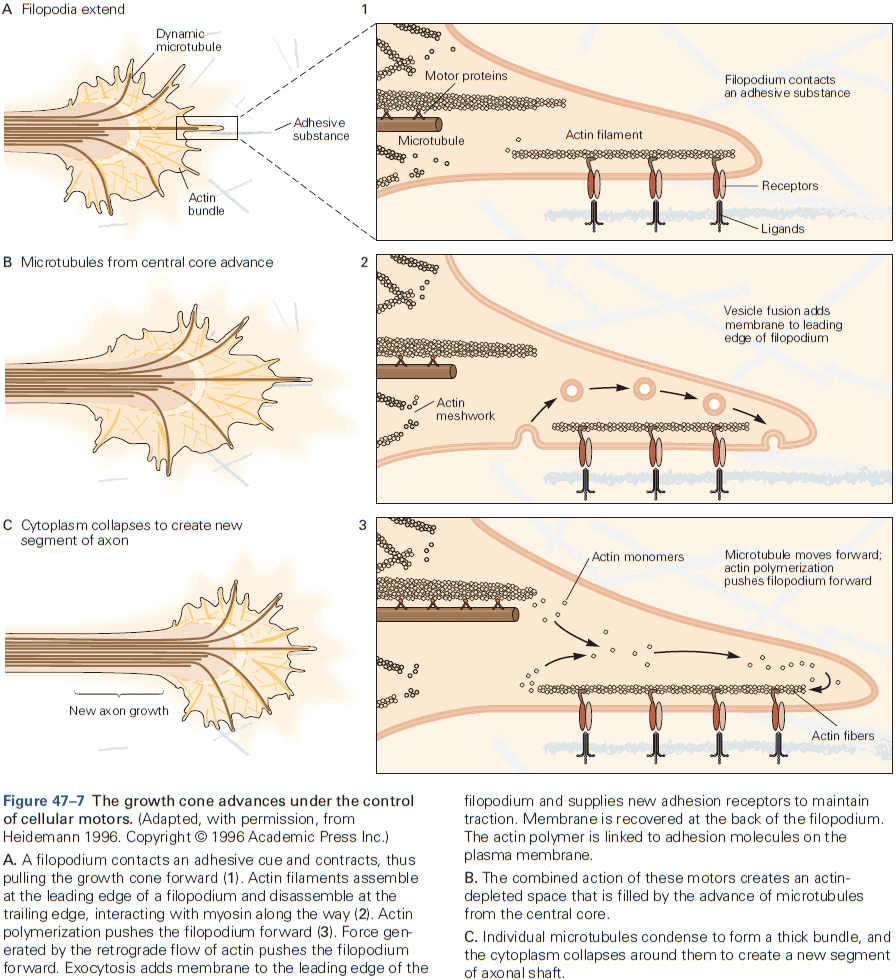

- Microtubules: long scaffolds from one end of a neuron to the other and play a key role in developing and maintaining cell shape.

- Neurofilaments: the bones of the cytoskeleton.

- Microfilaments: the thinnest of the three main types of fibers.

- Like microtubules, microfilaments undergo cycles of polymerization and depolymerization.

- The dynamic state of microtubules and microfilaments allows a mature neuron to retract old axons and dendrites and to extend new ones.

- This structural plasticity is thought to be a major factor in changes of synaptic connections and efficacy, therefore it’s a part of the cellular mechanisms of long-term memory and learning.

- Microtubules are arranged in parallel in the axon with plus ends pointing away from the cell body and minus ends facing the cell body.

- This allows some organelles to move towards and others to move away from nerve endings.

- Because axons and terminals often lie at great distances from the cell body, such as over 10,000 times the cell body diameter in leg motor neurons, sustaining the function of these remote regions presents a challenge.

- E.g. How are nutrients, proteins, and molecules transported to the axon terminal?

- Membrane and secretory products formed in the cell body must be actively transported to the end of the axon.

- Two types of axoplasmic flow

- Fast axonal transport: membranous organelles move toward axon terminals (anterograde) and back (retrograde) at speeds of up to 400 mm per day.

- Slow axonal transport: cytosolic and cytoskeletal proteins only move toward axon terminals at speeds of 0.2 to 2.5 mm per day.

- Microtubules provide a stationary track on which specific organelles can be moved by molecular motors.

- Fast retrograde transport also delivers signals that regulate gene expression in the neuron’s nucleus.

- E.g. Activated growth factor receptors at nerve endings are taken up into vesicles and transported back along the axon to the nucleus. This informs the genes transcription apparatus and can result in nerve regeneration and axon regrowth.

- Retrograde fast transport is about one-half to two-thirds the speed of anterograde fast transport.

- Skipping over protein synthesis details in neurons.

- CNS myelin is similar but not identical to PNS myelin.

- E.g. One Schwann cell produces a single myelin sheath for one segment of one axon, while one oligodendrocyte produces myelin sheaths for segments of as many as 30 axons.

- The number of myelin layers on an axon is proportional to the diameter of the axon.

- E.g. Larger axons have thicker sheaths, while small axons aren’t myelinated.

- Astrocytes play important roles in nourishing neurons and in regulating the concentrations of ions and neurotransmitters in the extracellular space.

- E.g. Astrocytes express many of the same voltage-gated ion channels and neurotransmitter receptors that neurons do so they may receive and transmit signals that could affect neuronal excitability and synaptic function.

- How do astrocytes regulate axonal conduction and synaptic activity?

- One way is by acting as a spatial buffer. When neurons fire, they release potassium ions into the extracellular space and astrocytes take up the excess ions and release it at distant contacts with blood vessels.

- Astrocytes also regulate neurotransmitter concentrations in the brain.

- E.g. Clearing glutamate from the synaptic cleft by ingesting and converting it into glutamine. Glutamine is then transferred to neurons where it servers as an immediate precursor of glutamate.

- Astrocytes also degrade dopamine, norepinephrine, epinephrine, and serotonin.

- An increase in free calcium ions within one astrocyte increases calcium ion concentrations in adjacent astrocytes, which leads to a calcium ion wave that propagates through the astrocyte network, enhancing synaptic function and behavior.

- Astrocyte-neuron signaling contributes to normal neuronal circuit functioning.

- Astrocytes are also important for the development of synapses.

- E.g. They secrete synaptogenic factors that promote the formation of new synapses, and can remodel and eliminate excess synapses by phagocytosis, thus contributing to learning and memory.

- Unlike neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, microglia are poorly understood.

- During development, microglia help sculpt developing neural circuits by engulfing pre- and post-synaptic structures.

Highlights

- The morphology or structure of neurons is elegantly suited to receive, conduct, and transmit information in the brain.

- E.g. Dendrites and axons.

- Neurons in different locations differ in the complexity of their dendritic trees, axon branching, and number of synaptic terminals. The functional significance of these morphological differences is evident.

- E.g. Motor neurons must have a more complex dendritic tree than sensory neurons because controlling muscles requires integrating many inputs, not outputs.

- Different types of neurons use different neurotransmitters, ion channels, and neurotransmitter receptors. All of these contribute to the great complexity of information processing in the brain.

- Neurons are among the most highly polarized cells in our body.

- The cytoskeleton provides an important framework for the transport of organelles to different intracellular locations in addition to controlling axonal and dendritic morphology.

- All of these fundamental cell biological processes are modifiable by neuronal activity, providing the mechanisms behind how neural circuits adapt to experience (learning).

- The nervous system contains several types of glial cells.

- E.g. Oligodendrocytes and Schwann cells produce myelin insulation that enable axons to conduct electrical signals rapidly. Astrocytes and nonmyelinating Schwann cells cover other parts of the neuron, mainly synapses.

- E.g. Astrocytes also control extracellular ion and neurotransmitter concentrations and actively participate in the formation and function of synapses.

- E.g. Microglia resident immune cells have diverse roles in health and disease.

- The cells in the choroid plexus and ependymal layer contribute to CSF production, composition, and dynamics.

Chapter 8: Ion Channels

- Signaling in the brain depends on the ability of neurons to respond to very small stimuli changes with rapid and large changes in the electrical potential difference across the cell membrane.

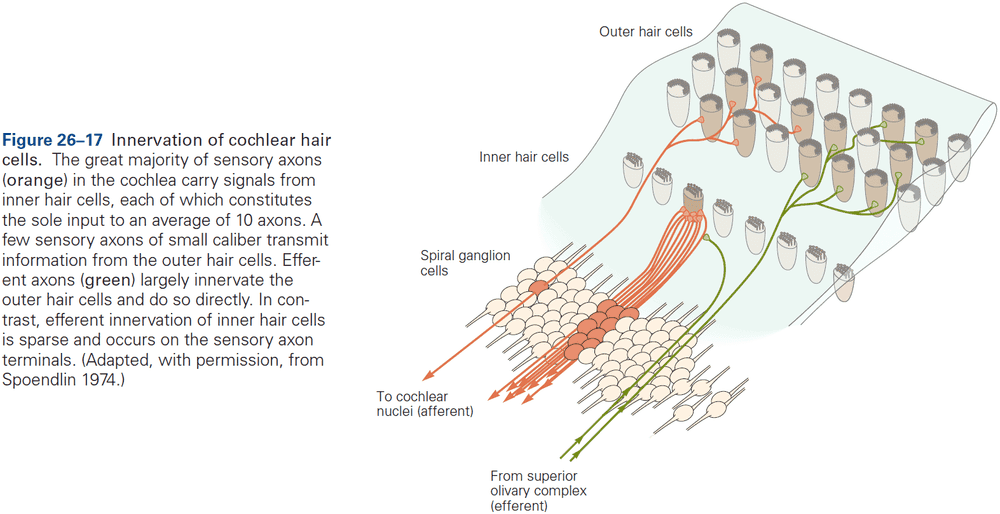

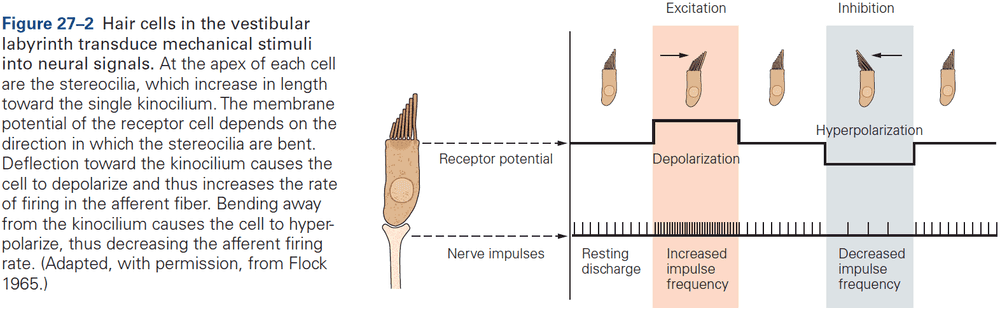

- E.g. Retinal neurons respond to a single photon of light, olfactory neurons detect a single odorant molecule, and hair cells in the inner ear respond to tiny movements of atomic dimensions.

- The rapid changes in membrane potential are mediated by specialized pores or openings in the membrane called ion channels.

- Ion channel: a class of membrane proteins found in all cells of the body that respond to specific physical and chemical signals.

- Since ion channels play key roles in electrical signaling, malfunctioning of such channels can cause a wide variety of neurological diseases.

- E.g. Cystic fibrosis and certain types of cardiac arrhythmia.

- Thus, ion channels have crucial roles in both the normal physiology and pathophysiology of the nervous system.

- Also crucial for neurons are proteins specialized for moving ions across cell membranes called ion pumps.

- Ion pumps don’t participate in rapid neuronal signaling but rather are important for establishing and maintaining the concentration gradients of physiologically important ions between the inside and outside of the cell.

- Three important properties of ion channels

- They recognize and select specific ions.

- They open and close in response to specific electrical, chemical, or mechanical signals.

- They conduct ions across the membrane.

- Up to 100 million ions can pass through a single channel each second, which causes the rapid changes in membrane potential required for signaling.

- A key to the great versatility of neuronal signaling is the regulated activation of different classes of ion channels, each of which is selective for specific ions.

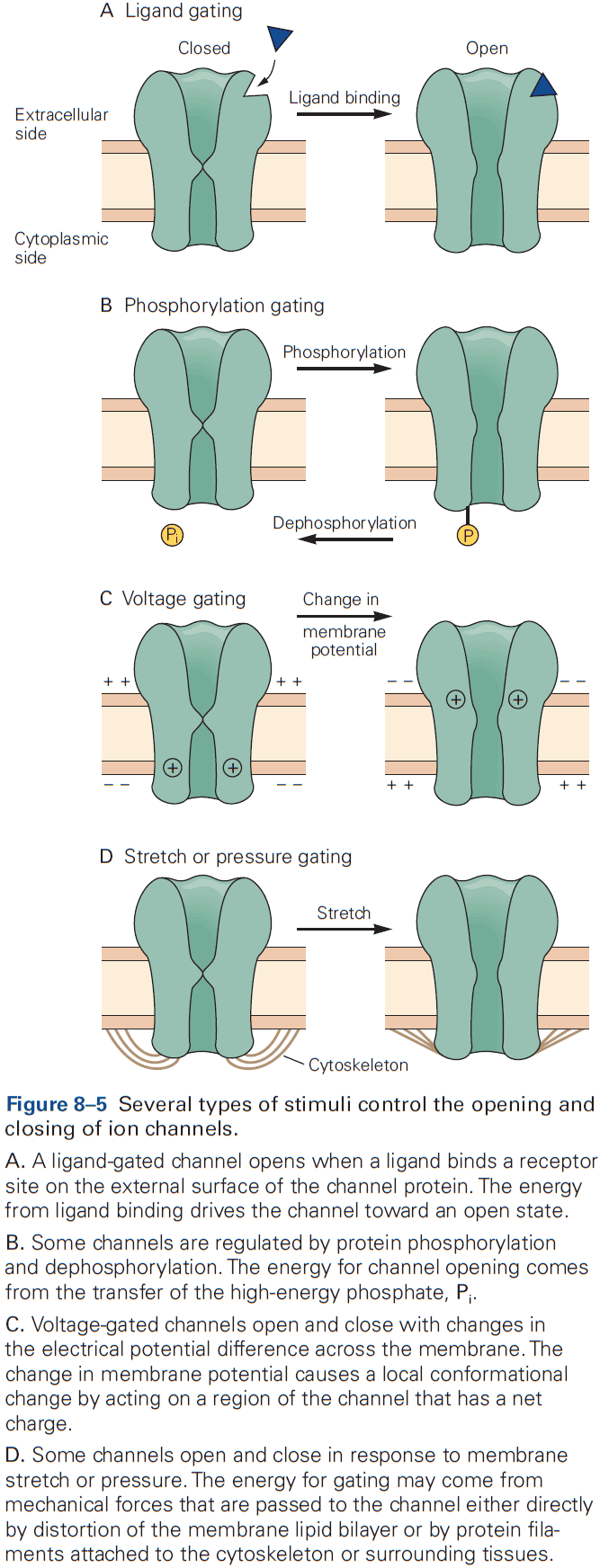

- E.g. Voltage-gated channels controlled by changes in membrane potential, ligand-gated channels controlled by the binding of chemical transmitters, and mechanically-gated channels controlled by membrane stretch.

- With only passive ion movement using ion channels, the ion concentration gradient would eventually dissipate were it not for ion pumps.

- Different types of ion pumps maintain the concentration gradients for sodium, potassium, calcium, and other ions.

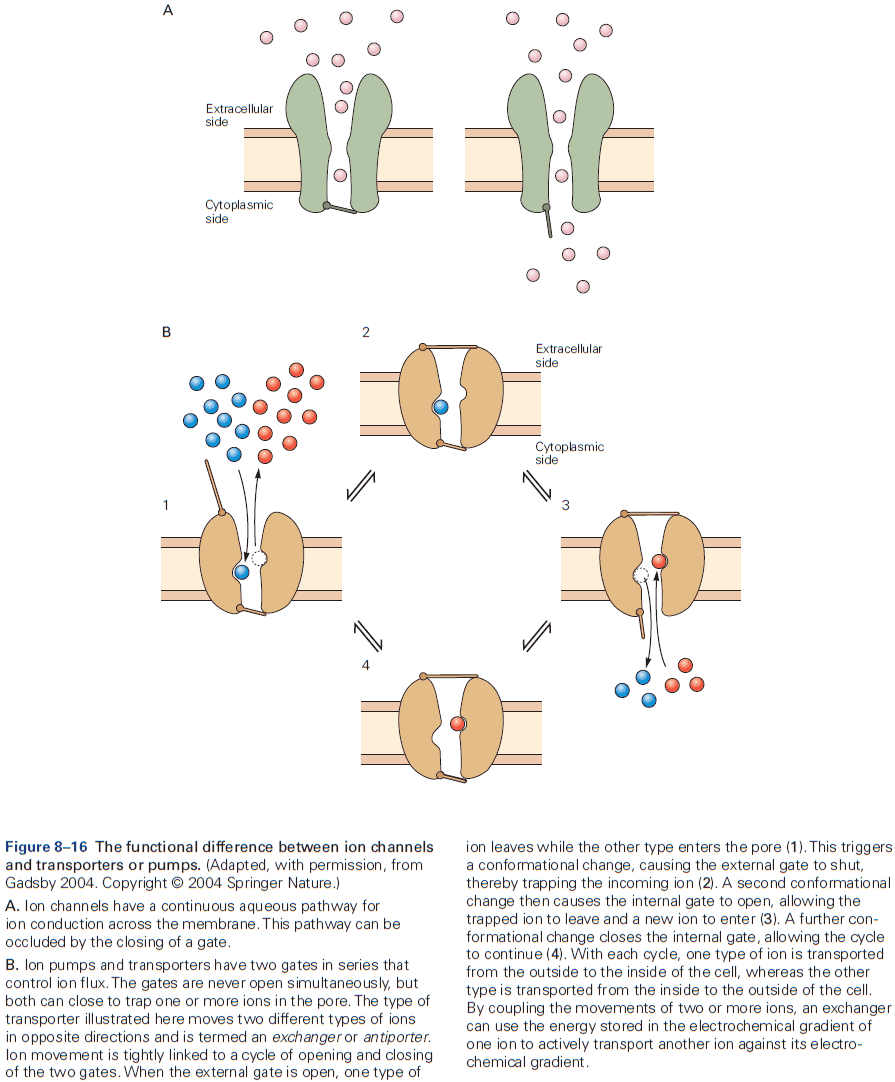

- Two features that distinguish ion pumps from ion channels

- The rate of ion flow through pumps is 100 to 100,000 times slower than through channels.

- Pumps use energy in the form of ATP to transport ions against their electrical and chemical gradients.

- Resting channels and pumps generate the resting potential, voltage-gated channels generate the action potential, and ligand-gated channels produce synaptic potentials.

- The lipid bilayer that makes up the cell membrane is uncharged, which makes it almost impermeable to ions.

- This is why cells have ion channels, to bypass the cell membrane and allow ions in or out.

- It’s currently hypothesized that ion channels are selective both because of specific chemical interactions and because of molecular sieving based on pore diameter.

- Most cells are capable of local signaling, but only nerve and muscle cells are specialized for rapid signaling over long distances.

- All cell share ion channels with several functional characteristics and neurons are no exception.

- The rapid rate that an ion unbinds to a channel is necessary to achieve the very high conduction rates responsible for the rapid changes in membrane potential during signaling.

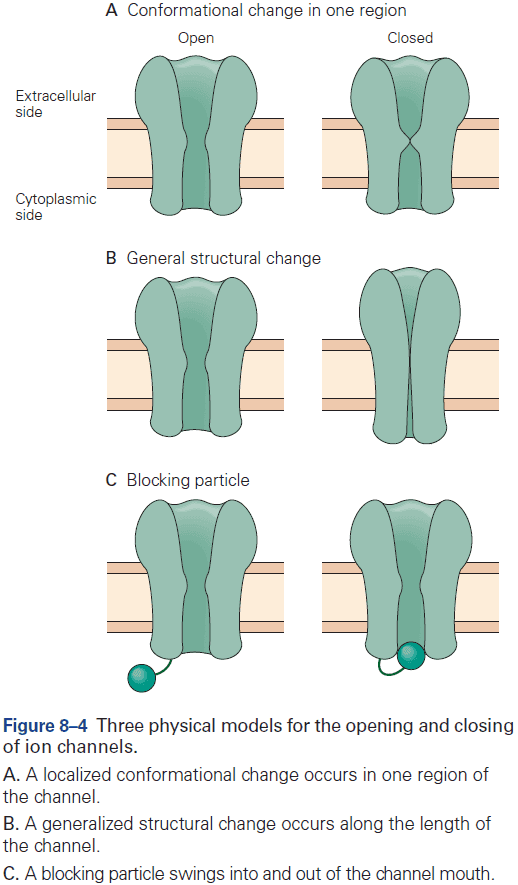

- The opening and close of a channel involves conformational changes and each channel has two or more conformational states.

- Three types of conformational changes

- Change in one region

- Change in general structure

- Blocking particle

- Regulators can control the entry of a channel into one of three states

- Resting: closed and activatable.

- Inactive/Refractory: closed and not activatable.

- Active: open.

- A change in the functional state of a channel requires energy.

- E.g. Changes in membrane potential, change in chemical free energy from transmitter binding, or mechanical energy from distortion of the lipid bilayer.

- Stimuli that gate the channel also control the rates of transition between the open and closed states of a channel.

- For voltage-gated channels, the rates are dependent on membrane potential. Once a channel opens, it stays open for a few milliseconds, and after closing, it stays closed for a few milliseconds.

- Once the transition between open and closed states begins, it proceeds nearly instantaneously, thus giving rise to the abrupt, all-or-none, step-like changes in current through the channel.

- Ligand-gated and voltage-gated channels enter refractory states through different mechanisms.

- Ligand-gated channels enter the refractory state with prolonged exposure to the agonist, a process called desensitization (an intrinsic property of the interaction between ligand and channel).

- Voltage-gated channels enter a refractory state after opening, a process called inactivation.

- Antagonist molecules can interfere with normal gating by binding to the same site at which the endogenous agonist normally binds, preventing the channel from opening and blocking access of the agonist to the binding site.

- Skimming over the structure of ion channels.

- The snug fit between potassium ion channels and potassium ions helps explain the unusually high selectivity of these channels compared to other ion channels.

- E.g. Many channel pore diameters are significantly wider than the principal permeating ion, contributing to a lower degree of selectivity.

Highlights

- Ions cross cell membranes through two main classes of membrane proteins: ion channels and ion pumps/transporters.

- Most ion channels are selectively permeable to certain ions and this is determined by the part of the channel pore called the selectivity filter. The selectivity filter filters based on ion charge, size, and physicochemical interactions.

- Ion channels have gates that open and close in response to different signals and the gates control an ion channel’s three possible states: open, closed, and inactivated.

- Various types of ion channels are differentially expressed in different types of neurons and in different regions of neurons, contributing to the functional complexity and computational power of the nervous system.

- Active transport, which is mediated by ion pumps, enables ions to move across the membrane against their electrochemical gradient. The driving force comes either from chemical energy in the form of ATP or from an electrochemical potential difference.

Chapter 9: Membrane Potential and the Passive Electrical Properties of the Neuron

- Two types of ion channels

- Resting

- Gated

- Resting channels are mostly important for maintaining the resting membrane potential, the electrical potential across the membrane in the absence of signaling.

- Some resting channels are always open, while others are gated by changes in voltage but are also open at the negative resting potential.

- In contrast, most voltage-gated channels are closed when the membrane is at rest and require membrane depolarization to open.

- The resting membrane potential of neurons comes from the separation of charge across the cell membrane.

- At rest, the extracellular surface of a cell has an excess of positive charge, and the cytoplasmic/intercellular surface has an excess of negative charge. This is maintained due to the impermeable lipid bilayer.

- Membrane potential: a difference of electrical potential across the membrane.

- By convention, the potential outside the cell is defined as zero.

- The resting membrane potential is between -60 to -70 mV.

- All electrical signaling involves brief changes to the resting membrane potential caused by electric currents across the cell membrane.

- Depolarization: a decrease in charge separation leading to a more positive membrane potential.

- Hyperpolarization: an increase in charge separation leading to a more negative membrane potential.

- Electronic potentials: changes in membrane potential that don’t lead to the opening of gated ion channels.

- Hyperpolarizing responses and small depolarizations are almost always passive and don’t trigger an active response in the cell.

- However, when depolarization approaches a critical threshold, the cell responds by opening voltage-gated ion channels, which produces an all-or-none action potential (AP).

- Sodium and chloride ions are concentrated outside the cell, while potassium and organic anions are concentrated inside.

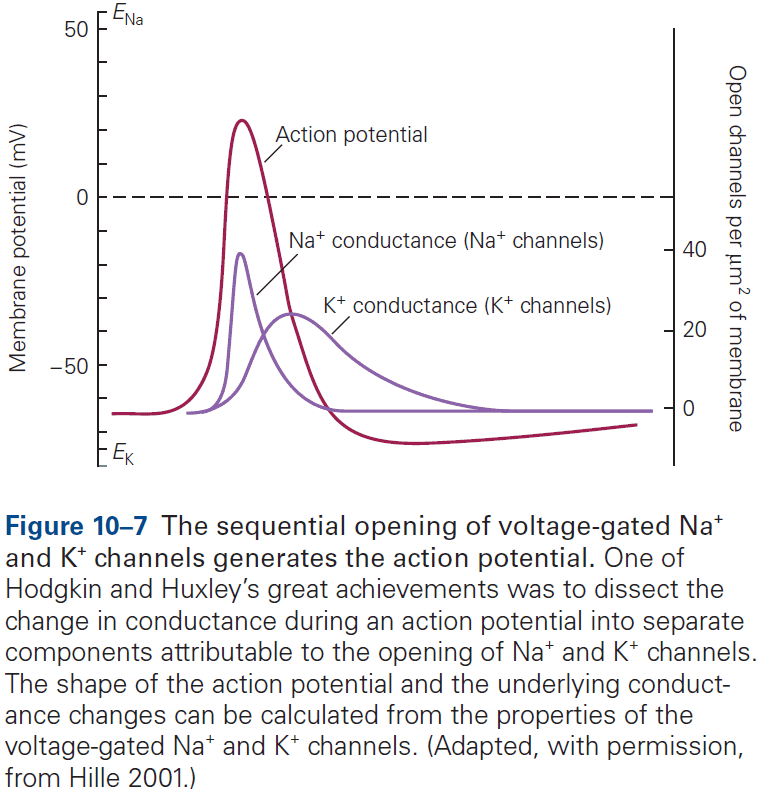

- Ions are subject to two forces driving them across the membrane

- Chemical driving force: a function of the concentration gradient across the membrane.

- Electrical driving force: a function of the electrical potential difference across the membrane.

- Glia are only permeable to potassium ions while neurons are permeable to potassium, sodium, and chloride ions.

- Dissipation of ionic gradients is prevented by the sodium-potassium pump, which moves sodium and potassium ions against their electrochemical gradients.

- The sodium-potassium pump expels sodium from the cell and admits potassium using ATP.

- At the resting membrane potential, the cell isn’t in equilibrium but rather in a steady state.

- Skimming over the math behind the resting potential and equivalent circuit for the resting membrane potential.

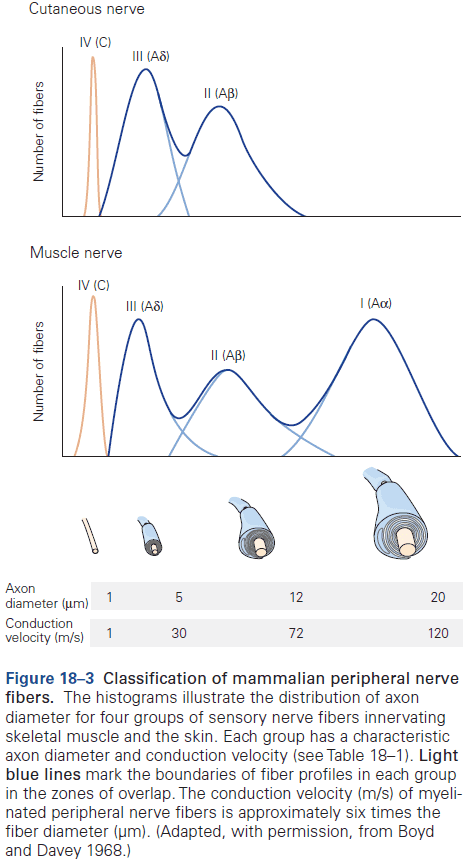

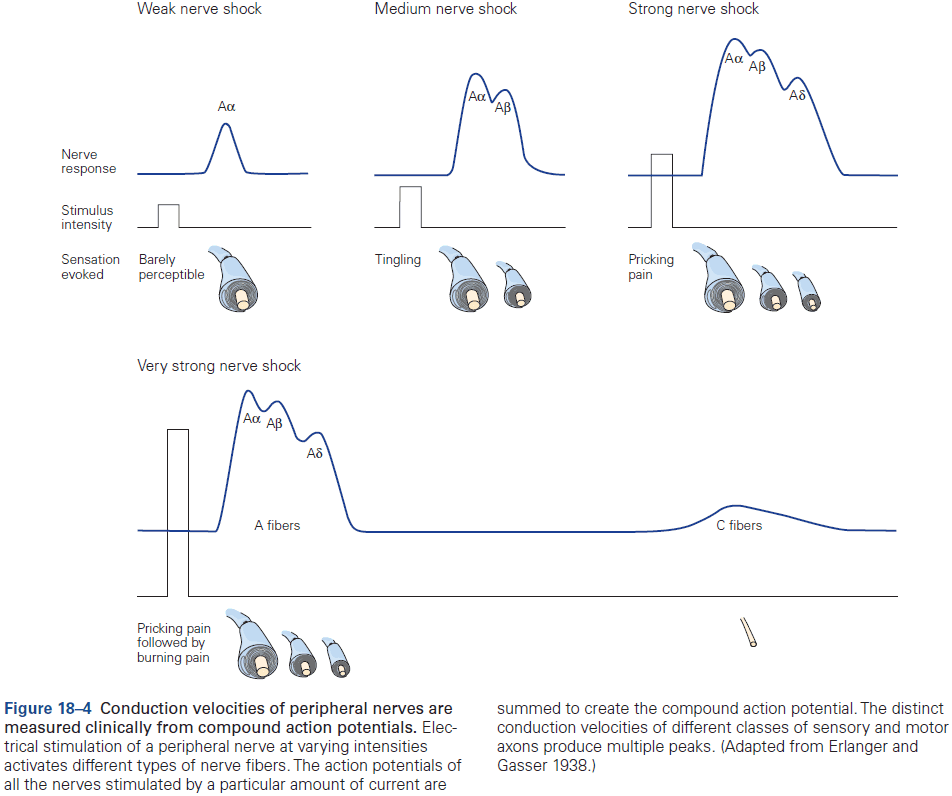

- Generally, axons with the largest diameter have the lowest threshold for excitation.

- Neurons that convey different types of information often differ in axon diameter and conduction velocity.

- The nodes of Ranvier are packed with voltage-gated sodium ion channels and periodically boost the amplitude of the AP, thus preventing it from decaying with distance.

Highlights

- At rest, the passive fluxes of ions into and out of cells are balanced, resulting in charge separation and the resting membrane potential.

- The ion permeability of the cell membrane is proportional to the number of open channels that allow ions to pass.

- Changes in membrane potential that generate neuronal electrical signals (action potentials, synaptic potentials, and receptor potentials) are caused by changes in the membrane’s relative permeability to potassium, chloride, sodium, and calcium ions.

- Ion pumps maintain the resting membrane potential by using ATP to exchange internal sodium ions for external potassium ions.

- For pathways where fast signaling is important, conduction of APs is enhanced by myelination of the axon, increasing axon diameter, or both.

Chapter 10: Propagated Signaling: The Action Potential

- Neurons can carry electrical signals over long distances because the AP is continually regenerated and thus, isn’t attenuated/decayed as it moves down the axon.

- Four important properties of APs

- Is only initiated when the membrane potential reaches a threshold.

- Is an all-or-none event.

- Is conducted without decay as it has a self-regenerative feature that keep the amplitude constant.

- Is followed by a refractory period where the neuron’s ability to fire a second AP is suppressed.

- The refractory period limits the frequency that neurons can fire APs and thus limits the information-carrying capacity of the axon.

- These four properties are unusual for biological processes, which typically respond in a graded manner to changes in the environment.

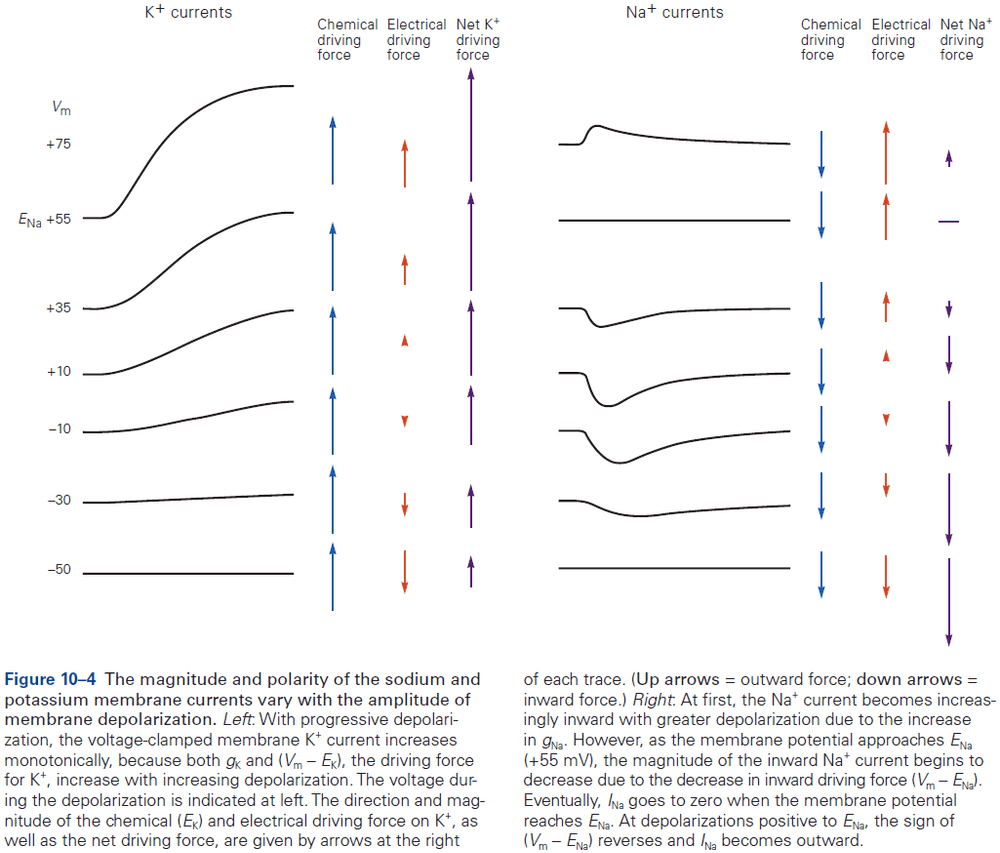

- The AP is generated by the flow of ions through voltage-gated channels.

- The AP can be reconstructed from the properties of sodium and potassium channels.

- The Hodgkin and Huxley mathematical model of the AP almost perfectly matches the experimentally recorded AP.

- According to the model, an AP involves the following sequence of events

- Depolarization of the membrane causes sodium ion channels to open, resulting in an inward sodium current.

- This current depolarizes the membrane, causing more sodium channels to open resulting in the rising phase of the AP.

- The depolarization gradually inactivates the voltage-gated sodium channels and, with some delay, opens the voltage-gated potassium channels.

- Although each step in the model is gradual, the all-or-none phenomenon of the AP is due to the runaway effect of the voltage-gated sodium channels open due to depolarization, which causes more depolarization, which causes more channels to open, etc.

- Review of the absolute and relative refractory period.

- The squid axon that Hodgkin and Huxley studied was unusually simple in that it only expressed two types of voltage-gated ion channels in comparison to the mammalian brain’s dozens or more.

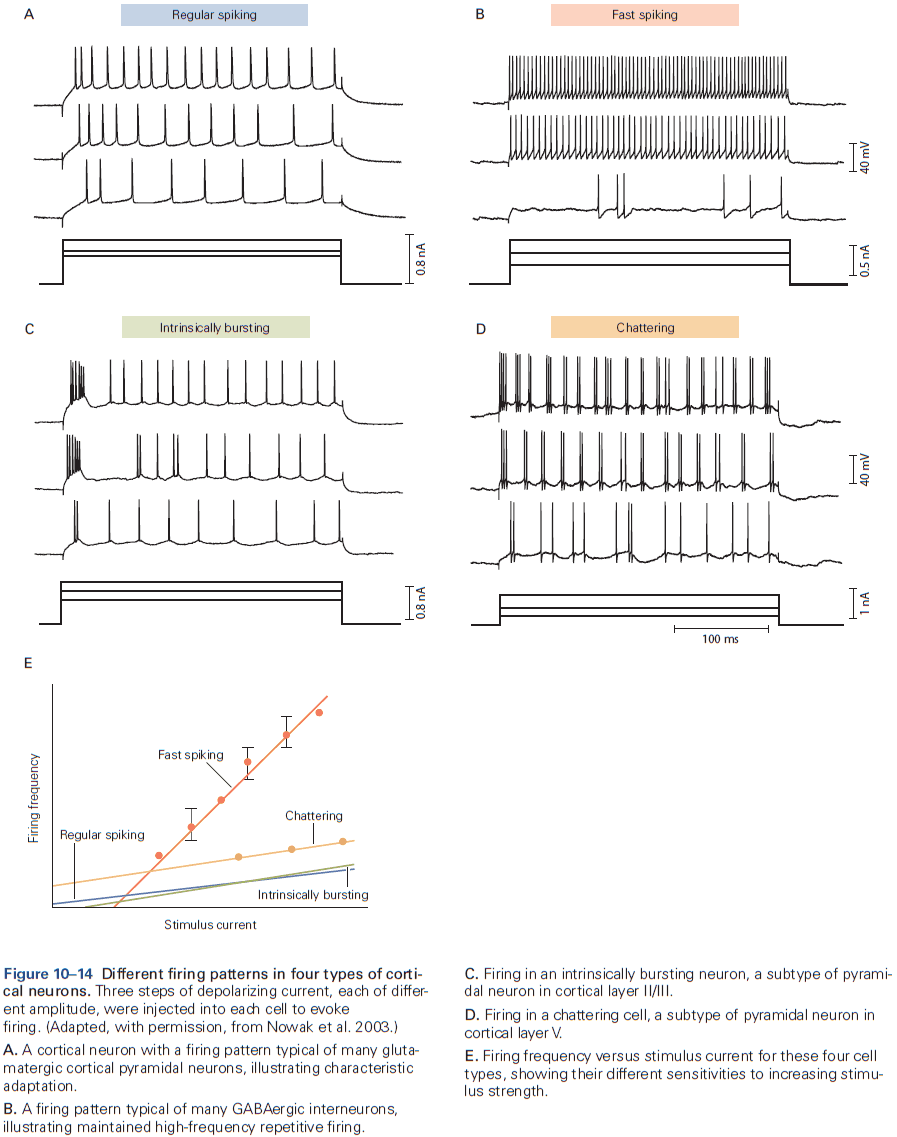

- The great variety of voltage-gated channels in the membranes of most neurons enables a neuron to fire APs with a much greater range of frequencies and patterns than is possible in the squid axon, allowing for more complex information processing and control.

- Skipping over the diversity of voltage-gated channels.

- The electrical properties of different neurons have evolved to match the dynamic needs of information processing.

- The function of a neuron isn’t only defined by its synaptic inputs and outputs, but also by its intrinsic excitability properties.

- Different types of neurons in the mammalian nervous system generate APs that have different shapes and fire different patterns, reflecting different expression of voltage-gated channels.

- E.g. Cerebellar Purkinje neurons have high levels of Kv3 channel expression resulting in narrow APs, while dopaminergic neurons have high levels of voltage-activated calcium channels resulting in broad APs.

- The shape of the AP in a neuron isn’t always invariant, and can be dynamically regulated either intrinsically (repetitive firing) or extrinsically (synaptic modulation).

- The input-output function of a neuron can be characterized by the frequency and pattern of AP firing in response to injected current and stimuli.

- Some neurons can sustain repetitive firing at high frequencies up to 500 Hz.

- E.g. Mammalian auditory neurons.

- A surprisingly large number of neurons in the mammalian brain fire spontaneously in the absence of any synaptic input.

- E.g. Many neurons that release modulatory neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and acetylcholine, fire spontaneously, resulting in a constant release of transmitter.

- Excitability properties vary between regions of the neuron.

- E.g. The axon initial segment has the lowest threshold for AP generation, in part because it has an exceptionally high density of voltage-gated sodium channels.

- These channels play a critical role in transforming graded synaptic or receptor potentials into a train of APs.

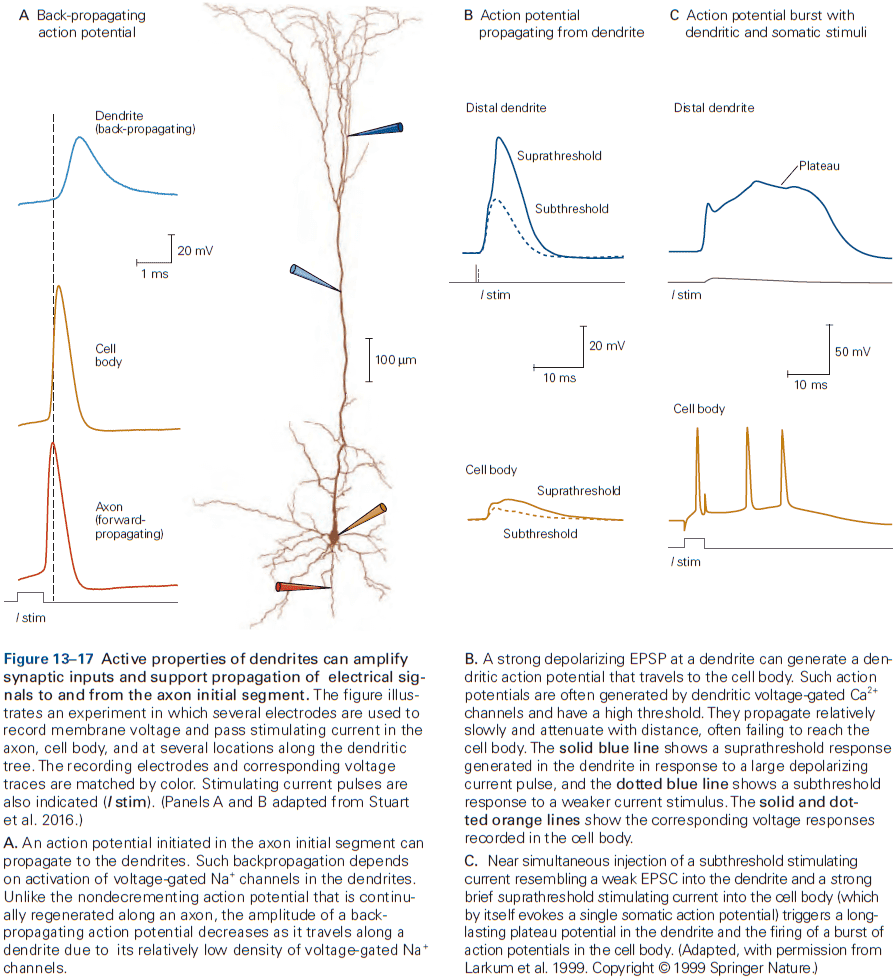

- Dendrites in many neurons have voltage-gated ion channels to help shape the amplitude, time course, and propagation of synaptic potentials to the cell body.

- In some neurons, the density of voltage-gated channels in dendrites is enough to support local APs. This may be used when the neuron generates an AP and it propagates back into the dendrites, serving as a signal to the synaptic regions that the cell has fired.

Highlights

- An action potential (AP) is a transient depolarization of membrane voltage lasting about 1 ms when ions move across the cell membrane through voltage-gated channels.

- In the depolarizing phase of the AP, sodium ions leave the cell. In the repolarizing phase, potassium ions enter the cell.

- The sharp threshold for AP generation happens at a voltage when the inward sodium current just exceeds outward potassium current through leak channels and voltage-gated channels.

- The refractory period reflects sodium channel inactivation and potassium channel activation after an AP. This limits the AP firing rate.

- Most neurons express multiple kinds of voltage-gated ion channels, which reflects the expression of multiple gene products.

- Activity of some voltage-gated ion channels can be modulated by cytoplasmic calcium ions.

- The regional expression and functional state of ion channels can be regulated in response to cell activity, changes in cell environment, or pathological processes, resulting in plasticity of the intrinsic excitability of neurons.

Part III: Synaptic Transmission

- In this part, we cover how neurons communicate with each other.

- Three components of the synapse

- Terminals of the presynaptic axon

- Target on the postsynaptic cell

- Zone of apposition

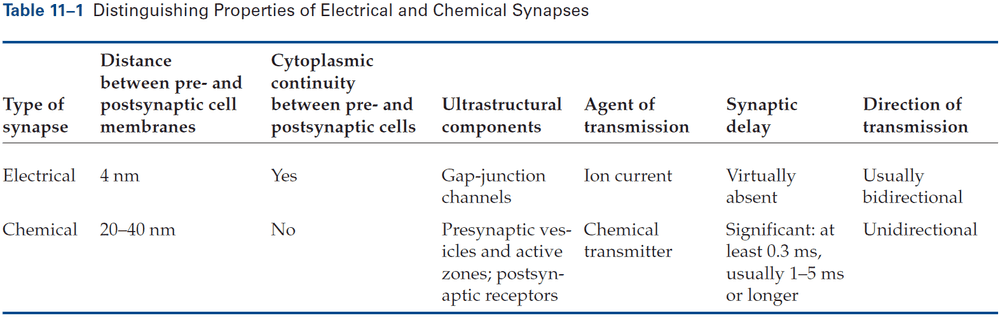

- Two types of synapses

- Electrical: when the presynaptic and postsynaptic cell are very close at regions called gap junctions and the current generated by an AP in the presynaptic neuron directly enters the postsynaptic cell.

- Chemical: when the presynaptic and postsynaptic cell are separated by the synaptic cleft and transmitter diffuses across, binding to receptor molecules on the postsynaptic membrane.

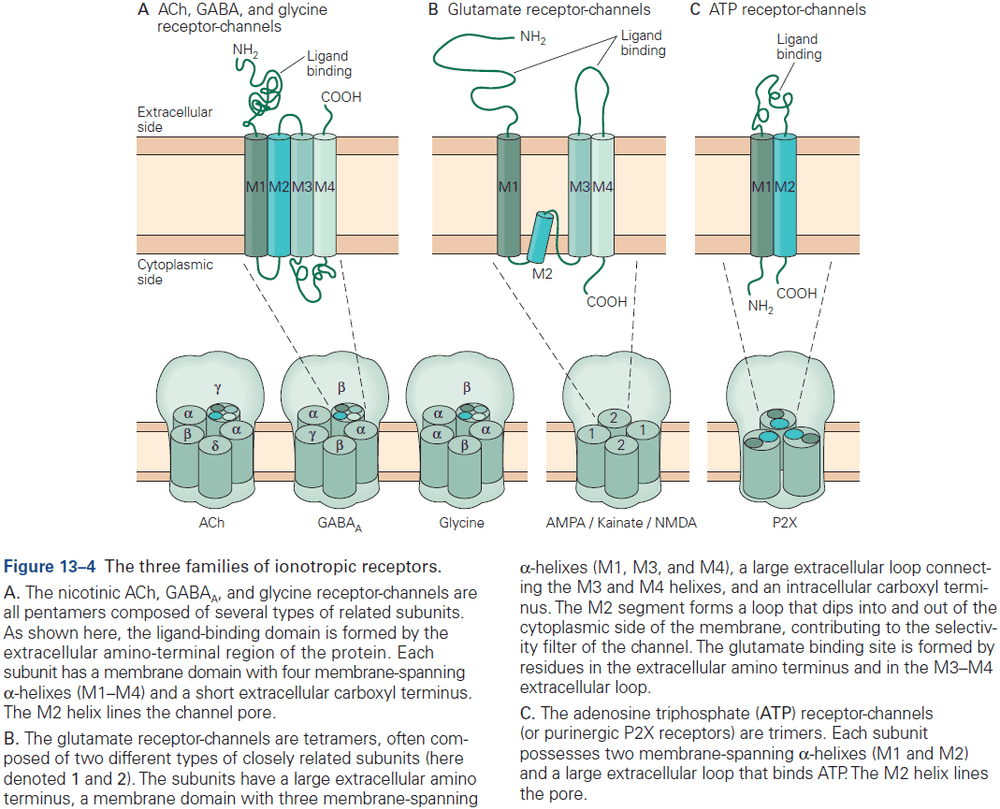

- Two types of transmitter receptors

- Ionotopic: when transmitter binding directly opens an ion channels..

- Metabotropic: when transmitter binding indirectly regulates a channel by activating secondary messengers.

- Both types of receptors can result in excitation or inhibition. This doesn’t depend on the identity of the transmitter but on the properties of the receptor that the transmitter interacts with.

- One key theme of this part and this book is the concept of plasticity. At all synapses, the strength of a synaptic connection isn’t fixed but can be modified in various ways by experience.

Chapter 11: Overview of Synaptic Transmission

- The average neuron forms thousands of synaptic connections and receives a similar number of inputs.

- E.g. Purkinje cells receive up to 100,000 synaptic inputs while granule neurons receive only four excitatory inputs.

- Electrical synapses are mostly used to send rapid depolarizing signals, while chemical synapses are used to produce more variable signaling.

- Chemical synaptic transmission is central to our understanding of the brain and behavior.

- Electrical synapses are virtually instantaneous as the postsynaptic response follows the presynaptic stimulation in a fraction of a millisecond.

- At an electrical synapse, when a weak depolarizing current is injected into the presynaptic neuron, some current enters the postsynaptic cell and depolarizes it.

- In contrast, at a chemical synapse, a depolarizing current injected into the presynaptic neuron must reach threshold for the release of transmitter to elicit a response in the postsynaptic cell.

- Most electrical synapses can transmit both depolarizing and hyperpolarizing currents.

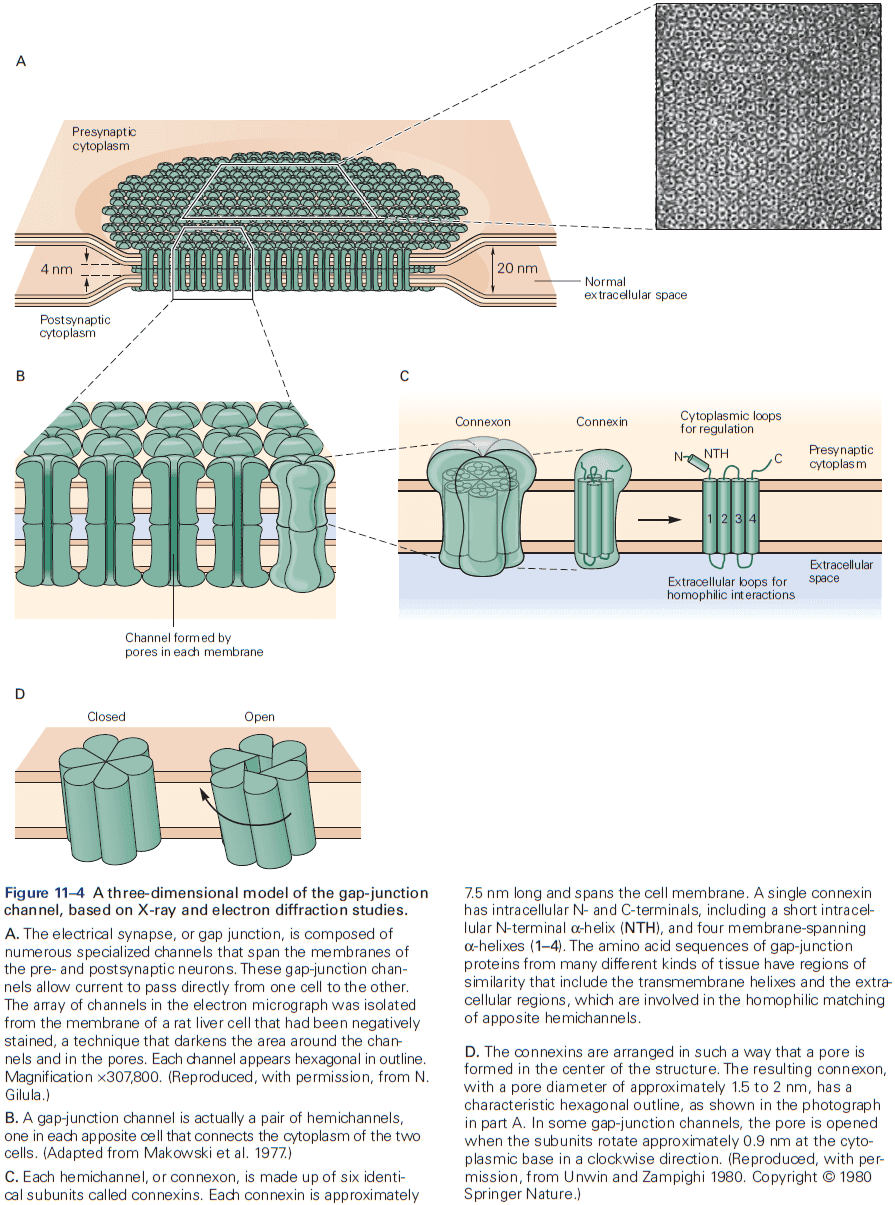

- The gap between electrical synapses is small at around 4 nm compared to the 20 nm for the normal nonsynaptic space between neurons.

- This narrow gap is bridged by gap-junction channels, specialized protein structures that conduct ionic current directly from the presynaptic to the postsynaptic cell.

- The pore of gap-junction channels is large at 1.5 nm compared to the 0.3-0.5 nm diameter of ion-selective ligand-gated or voltage-gated channels. This means the channel doesn’t select among ions and is even wide enough to allow small organic molecules to pass through.

- Electrical transmission allows rapid and synchronous firing of interconnected cells.

- E.g. The tail-flip response in goldfish and the ink response in Aplysia.

- Gap junctions are also formed between neurons and glia.

- E.g. A wave of calcium ions in astrocytes can cause neurotransmitter release in neurons. The precise function of these waves is unknown.

- The gap between chemical synapses is wide at around 20-40 nm and is sometimes bigger than the normal nonsynaptic space between neurons.

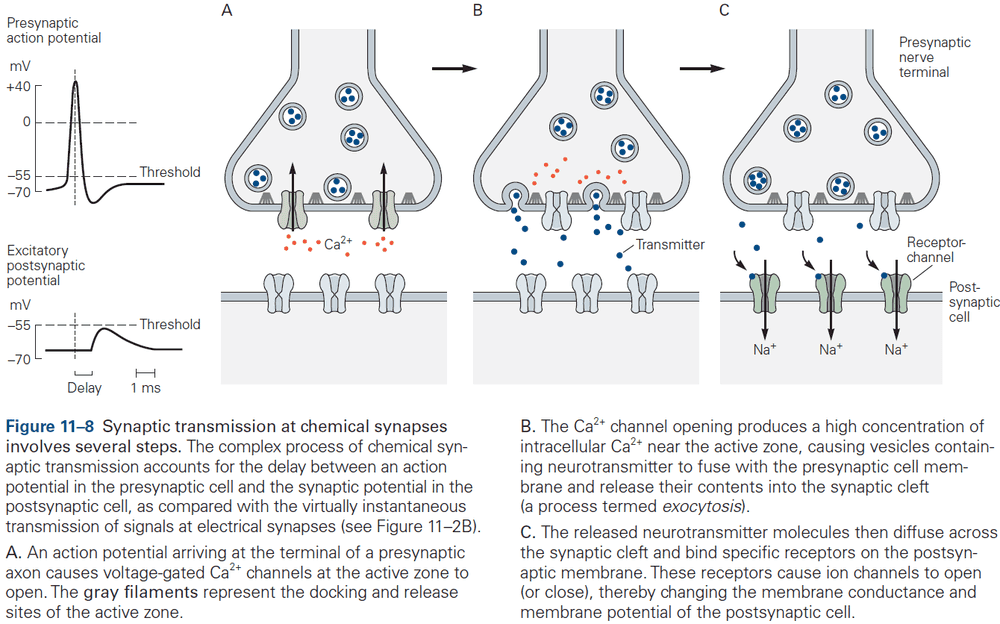

- Chemical synaptic transmission depends on a neurotransmitter.

- Neurotransmitter: a chemical substance that diffuses across the synaptic cleft, binds to receptors, and activates receptors in the membrane of the target cell.

- The neurotransmitter is released from specialized vesicles with a typical release having around 100-200 synaptic vesicles, each with several thousand molecules of neurotransmitter.

- The release is triggered by an increase in intracellular calcium ions, which causes the vesicles to fuse with the presynaptic membrane and release neurotransmitter into the synaptic cleft. This process is called exocytosis.

- The transmitter molecules then diffuse across the synaptic cleft and bind to receptors on the postsynaptic cell.

- This activates the receptors, leading to the opening or closing of ion channels, changing the membrane potential of the postsynaptic cell.

- These several steps account for the synaptic delay (around 1 ms or less) at chemical synapses.

- What chemical transmission lacks in speed it makes up for in amplification.

- E.g. A small presynaptic nerve terminal, which only generates a weak electrical current, can depolarize a large postsynaptic cell.

- Two steps of chemical synaptic transmission

- Transmitting: when the presynaptic cell releases a chemical messenger.

- Receptive: when the transmitter binds to and activates the receptor molecules in the postsynaptic cell.

- The transmitting step resembles endocrine hormone release as chemical synaptic transmission can be seen as a modified form of hormone secretion.

- However, the important difference between endocrine and synaptic signaling is that endocrine signaling isn’t targeted as it travels throughout the body, whereas synaptic signaling is targeted and precise to which neurons receive the neurotransmitter.

- Thus, chemical synaptic transmission is both fast and precise.

- The action of a transmitter depends on the properties of the postsynaptic receptors that recognize and bind the transmitter, not the chemical properties of the transmitter.

- E.g. ACh at neuromuscular junctions is excitatory and can trigger contraction, while at the heart is inhibitory and can slow it down.

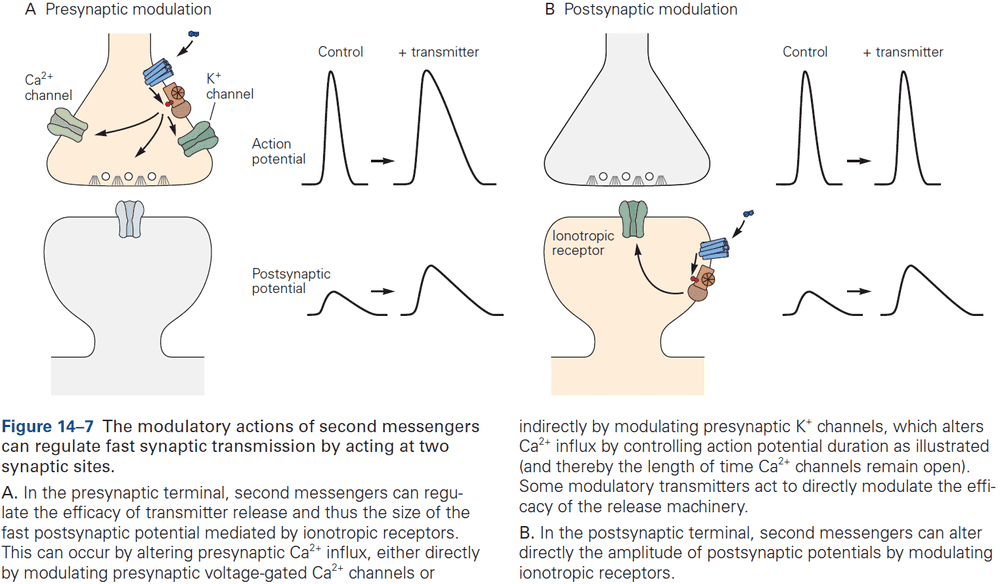

- Neurotransmitters control the opening of ion channels in the postsynaptic cell either directly or indirectly.

- Ionotropic: a receptor that directly controls ion flux.

- Metabotropic: a receptor that indirectly controls ion flux.

- Ionotropic and metabotropic receptors have different functions, with ionotropic producing relatively fast synaptic actions lasting only milliseconds, while metabotropic producing slower synaptic actions lasting hundreds of milliseconds to minutes.

- Electrical and chemical synapses can coexist and interact with each other in the same neuron, with each modifying the other’s efficacy.

- E.g. During development, many neurons are initially connected by electrical synapses that help form chemical synapses. As chemical synapses form, they often initiate the down-regulation of electrical transmission.

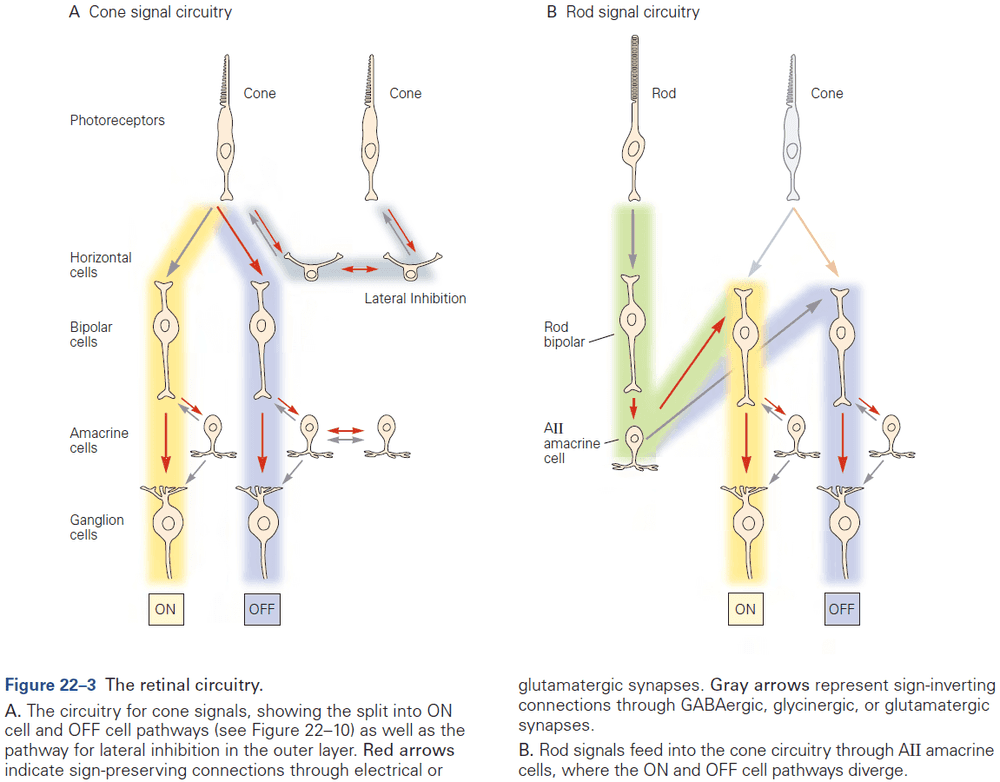

- E.g. In the retina, bipolar neurons form chemical synapses with rods and cones while also receiving electrical synapses between neighboring bipolar cells and amacrine cells.

Highlights

- Neurons communicate using electrical and chemical synaptic transmission.

- Electrical synapses are formed at tight regions that provide a direct pathway for charge to flow between the cytoplasm of communicating neurons. This results in fast transmission suited for synchronizing the activity of populations of neurons.

- Electrical synapses are connected through gap-junction channels.

- Chemical synapses use chemical transmitters to transmit signals from the presynaptic cell to the postsynaptic cell.

- Chemical transmission allows for amplification of the presynaptic AP through the release of tens of thousands of molecules of transmitter and activation of hundreds of thousands of receptors in the postsynaptic cell.

- The effect of a neurotransmitter is determined by the postsynaptic receptors, not the molecule.

- The two major classes of transmitter receptors are ionotropic and metabotropic.

Chapter 12: Directly Gated Transmission: The Nerve-Muscle Synapse

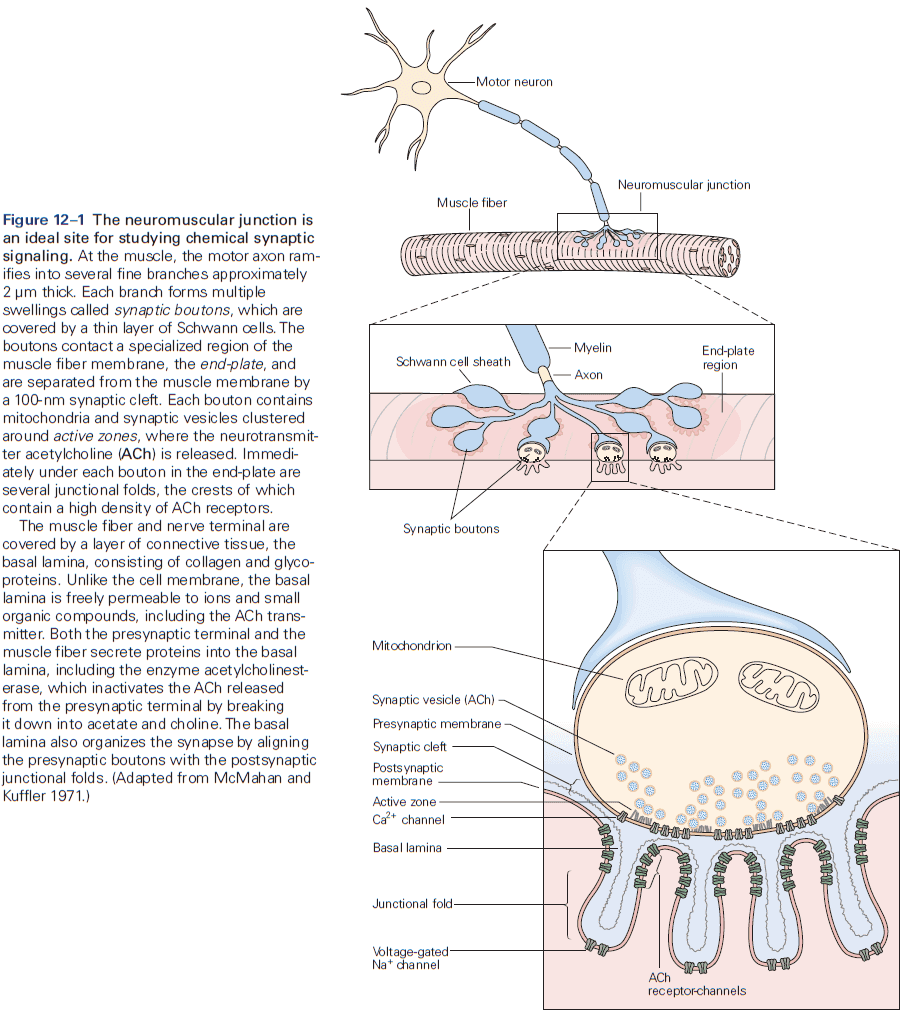

- Neuromuscular junction / end-plate: the site of contact between nerve and muscle.

- Synaptic boutons: the ends of axon branches.

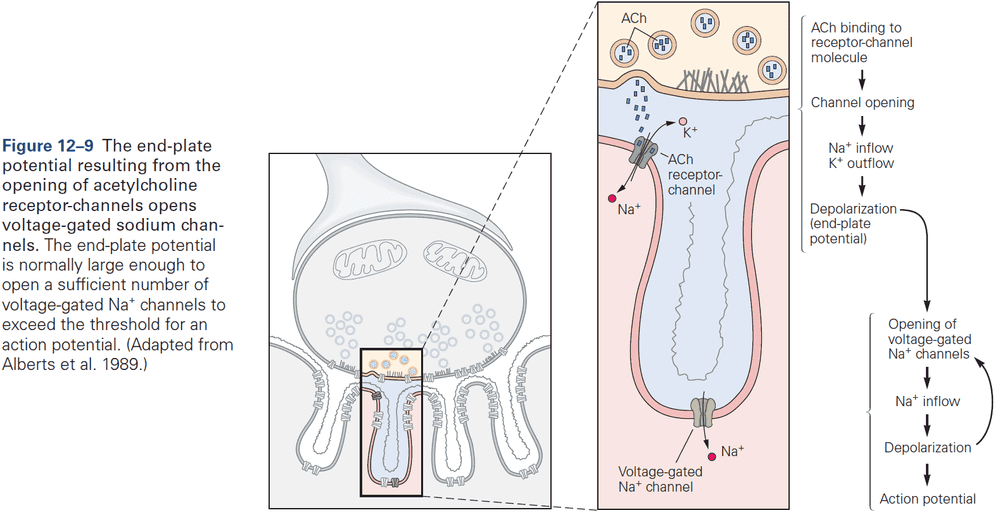

- When acetylcholine (ACh) is released into the end-plate, it rapidly binds to and opens the ACh receptor-channels in the end-plate membrane.

- This results in a large excitatory post-synaptic potential (EPSP) of about 75 mV.

- The combination of a very large EPSP and low threshold at the end-plate results in a high safety factor for triggering an AP in the muscle fiber.

- Muscles probably require this high safety factor as they can’t be undecided on whether to contract given a signal. Evolution pushed for high reliability in muscles.

- This contrasts with EPSPs in the CNS which are less than 1 mV, and that inputs from many presynaptic neurons are needed to generate an AP in most CNS neurons.

- The end-plate current rises and decays more rapidly than the end-plate potential because it takes times for an ionic current to charge or discharge the muscle membrane capacitance, so the membrane voltage (EPSP) lags behind the synaptic current (EPSC).

- Although individual ACh receptor-channels are noisy and undergo random thermal fluctuations, the average time a type of channel stays open is a well-defined property of that channel.

- Once a receptor-channel opens, what ions flow through the channel and how does this lead to depolarization?

- ACh receptor-channels at the end-plate aren’t selective for any ion species except for cations, so sodium, potassium, and calcium ions can flow through the channel leading to depolarization.

- Two main differences between ACh receptors (synaptic potential) and voltage-gated channels (action potential)

- The AP is generated by sequential activation of two distinct classes of voltage-gated channels, one selective for sodium ions and the other for potassium ions.

- The synaptic potential is only cation selective and allows both sodium and potassium ions to pass with near-equal permeability.

- The AP regenerates itself as incoming sodium ions depolarize the membrane potential, causing more voltage-gated sodium channels to open.

- The synaptic potential is dependent on the amount of ACh available and can’t produce an AP.

- If ACh is allowed to stay in the synaptic cleft for a long time, ACh receptors can become desensitized where they no longer conduct ions.

- Skipping over the structure of the ACh receptor-channel.

Highlights

- The terminals of motor neurons form synapses with muscle fibers at specialized regions in the muscle membrane called end-plates. When an AP reaches the terminal, it causes the release of ACh.

- ACh diffuses across the synaptic cleft, binding to ACh receptors and causing an inflow of cations such as sodium, potassium, and calcium.

- This inflow causes a large and local depolarization of around 75 mV, enough to exceed the AP threshold generation by a factor of three to four.

- This excessive depolarization is required to ensure that a neural signal is always converted into a muscle movement, which is essential for survival.

Chapter 13: Synaptic Integration in the Central Nervous System

- Many principles that apply to the synaptic connection between the motor neuron and skeletal muscle fiber at the end-plate also apply in the CNS.

- However, synaptic transmission between neurons in the CNS is more complex.

- E.g. More inputs from thousands of neurons, both excitatory and inhibitory inputs, many types of neurotransmitters, and not all APs produce an AP in the postsynaptic neuron.

- Typically, a depolarization of 10 mV or more is required to push a neuron past AP threshold.

- The effect of a synaptic potential, excitatory or inhibitory, isn’t determined by the type of transmitter released but by the type of ion channels in the postsynaptic cell activated by the transmitter.

- Some transmitters can produces both EPSPs and IPSPs but most transmitters produce a single type of synaptic response.

- E.g. Glutamate is typically excitatory while GABA is typically inhibitory.

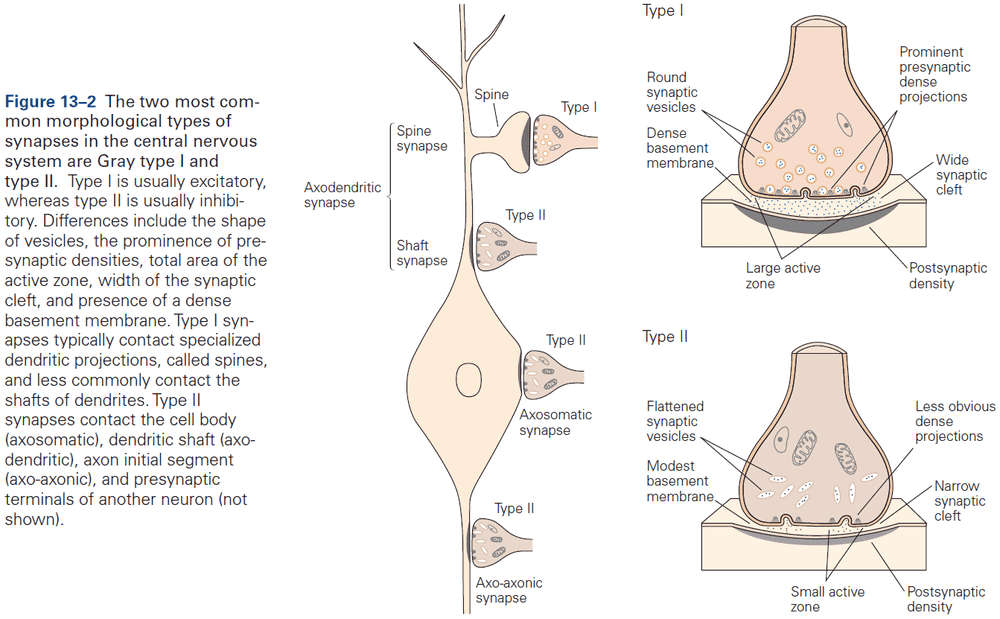

- We can determine whether a synaptic terminal is excitatory or inhibitory by it’s ultrastructure.

- Two morphological types of synapses

- Gray type I: glutamatergic and excitatory. Have round synaptic vesicles and contact dendritic spines.

- Gray type II: GABAergic and inhibitory. Have oval or flattened vesicles and contact dendritic shaft, cell body, or axon.

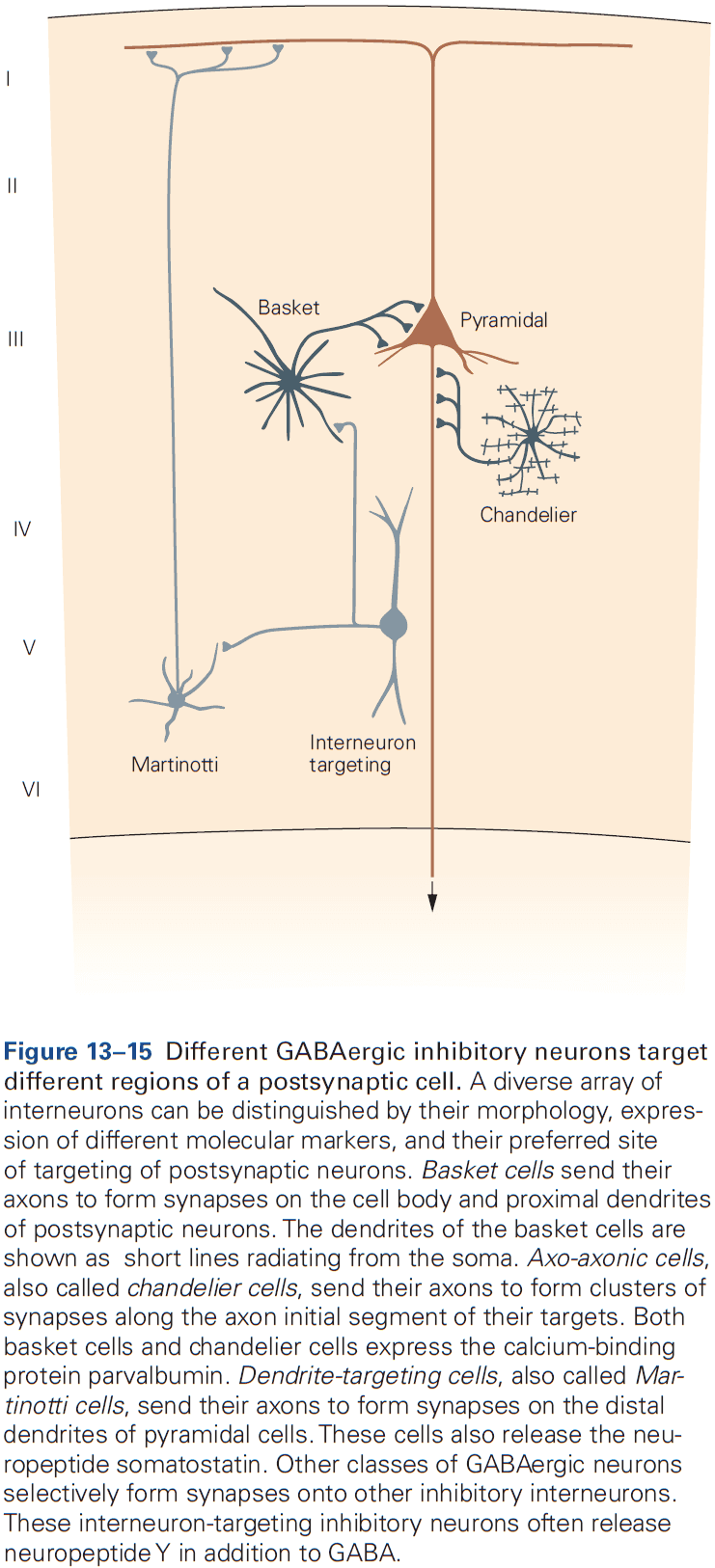

- Axon terminals are normally presynaptic and dendrites are normally postsynaptic, but any part of a neuron can be a presynaptic or postsynaptic site of chemical synapses.

- The most common types of contact are axodendritic, axosomatic, and axoaxonic.

- Excitatory synapses are typically axodendritic and occur mostly on dendritic spines.

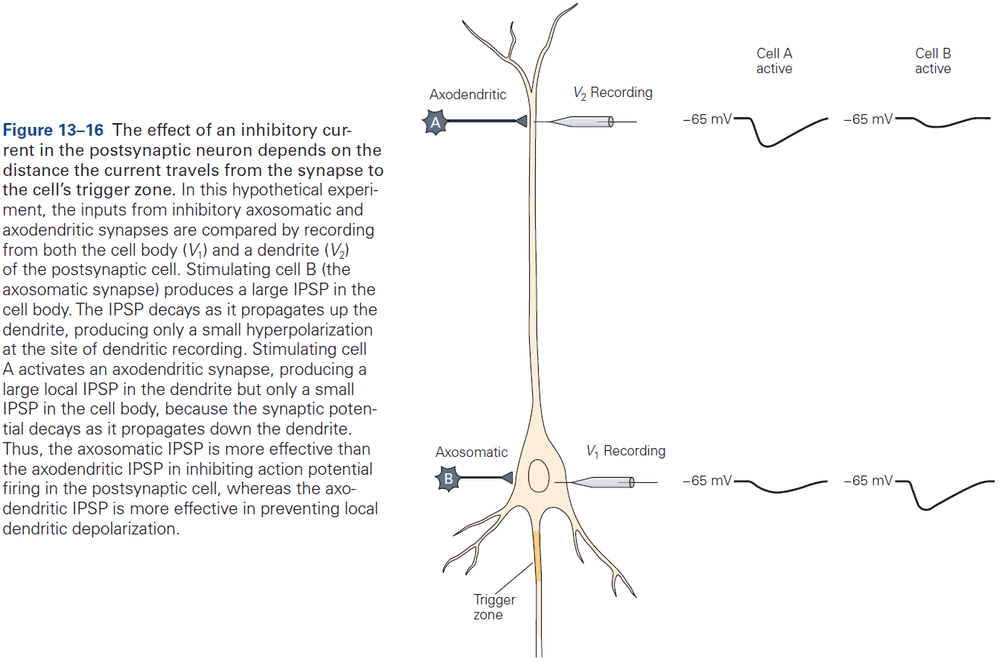

- Inhibitory synapses are typically found on dendritic shafts, cell body, and axon initial segment.

- As a general rule, the proximity of a synapse to the axon initial segment is thought to determine its effectiveness.

- E.g. The closer the synapse is to the axon initial segment, the greater the influence on AP output than at more remote sites due to less leakage.

- Some neurons compensate for this effect by having more receptors at distant synapses than at close synapses to ensure that inputs at different locations have more equal influence.

- Most axoaxonic synapses don’t have a direct effect on the trigger zone of a neuron, but instead control the amount of transmitter released from the presynaptic terminals.

- The three receptors of glutamate are NMDA, AMPA, and kainate.

- Three major types of ionotropic receptors

- ACh, GABA, and glycine

- Glutamate

- ATP

- Skipping over the detailed structure of the glutamate receptor.

- Most of the excitatory synapses in the mature nervous system have both NMDA and AMPA receptors, compared to in early development where synapses mostly have only NMDA receptor.

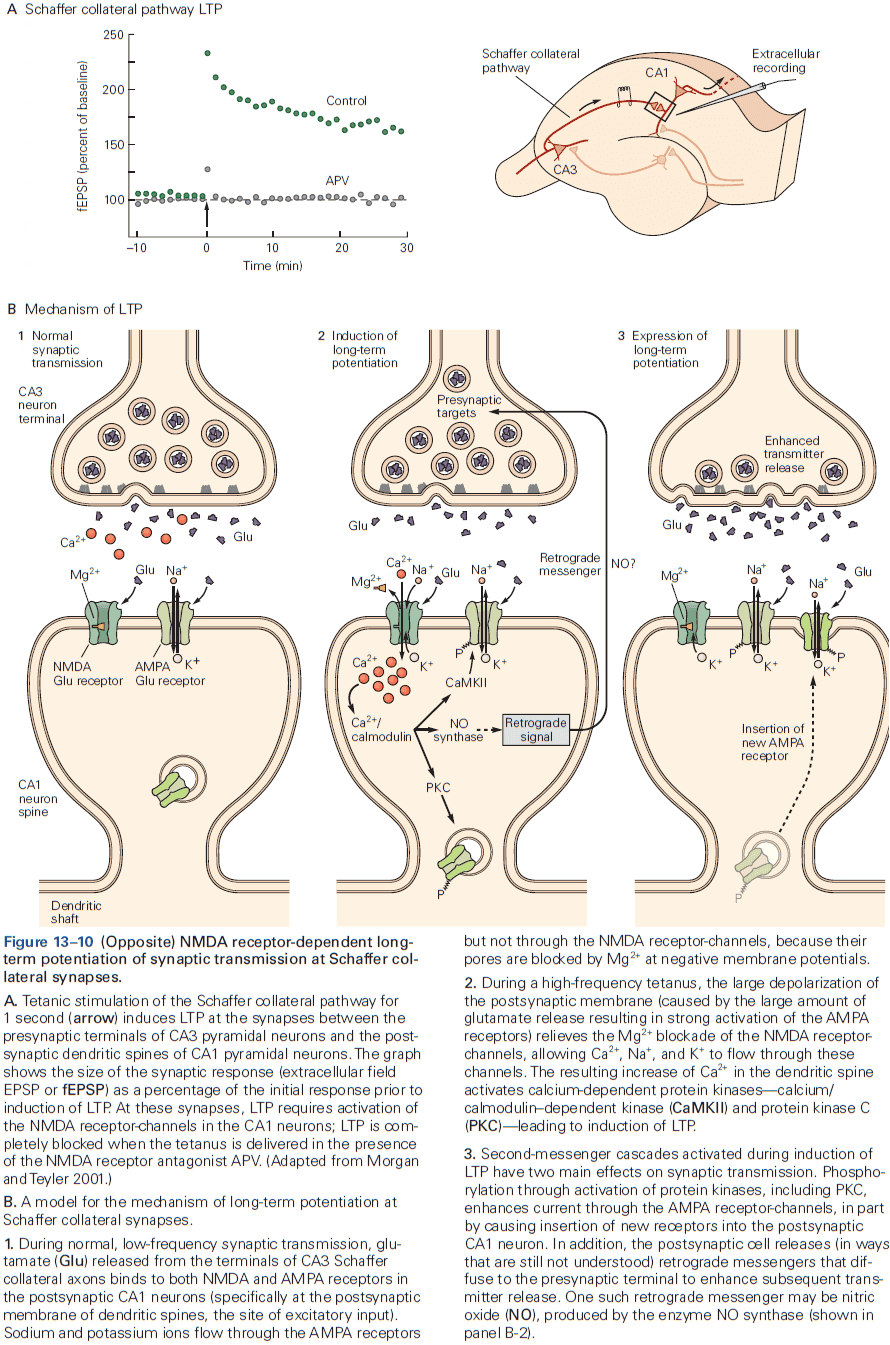

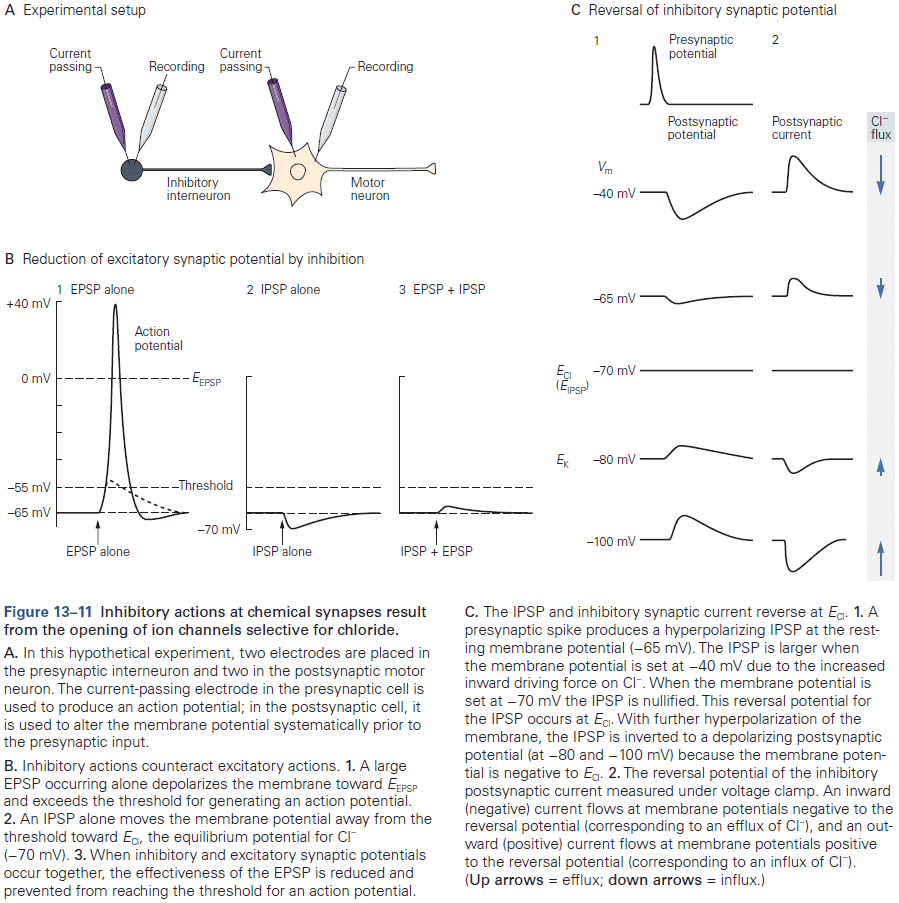

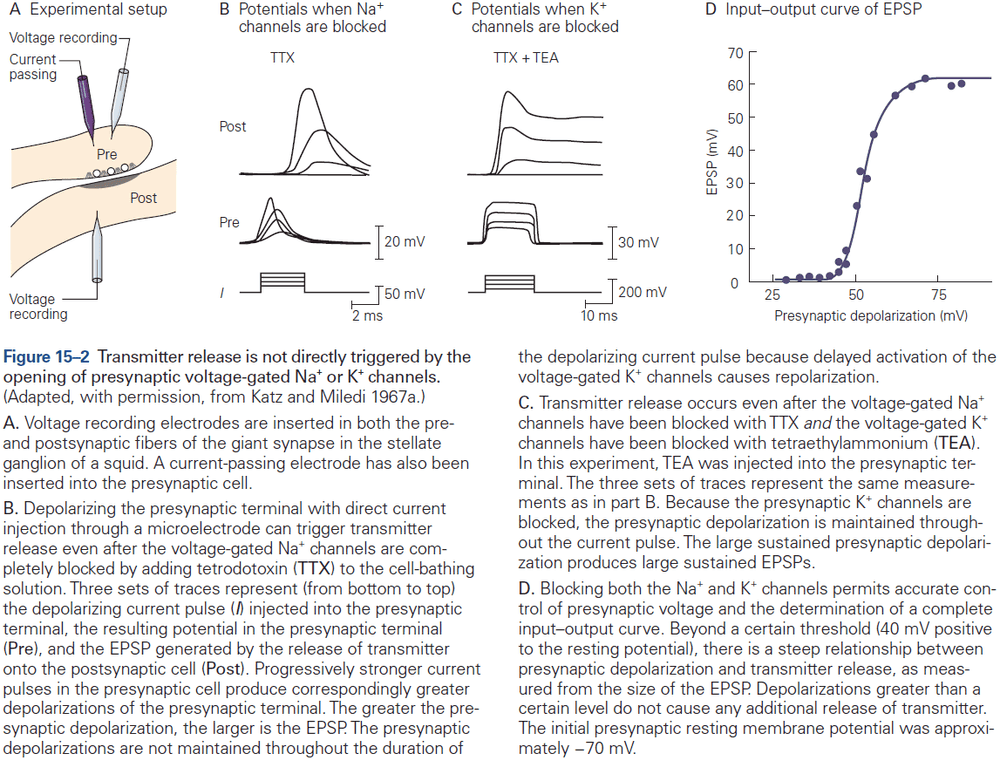

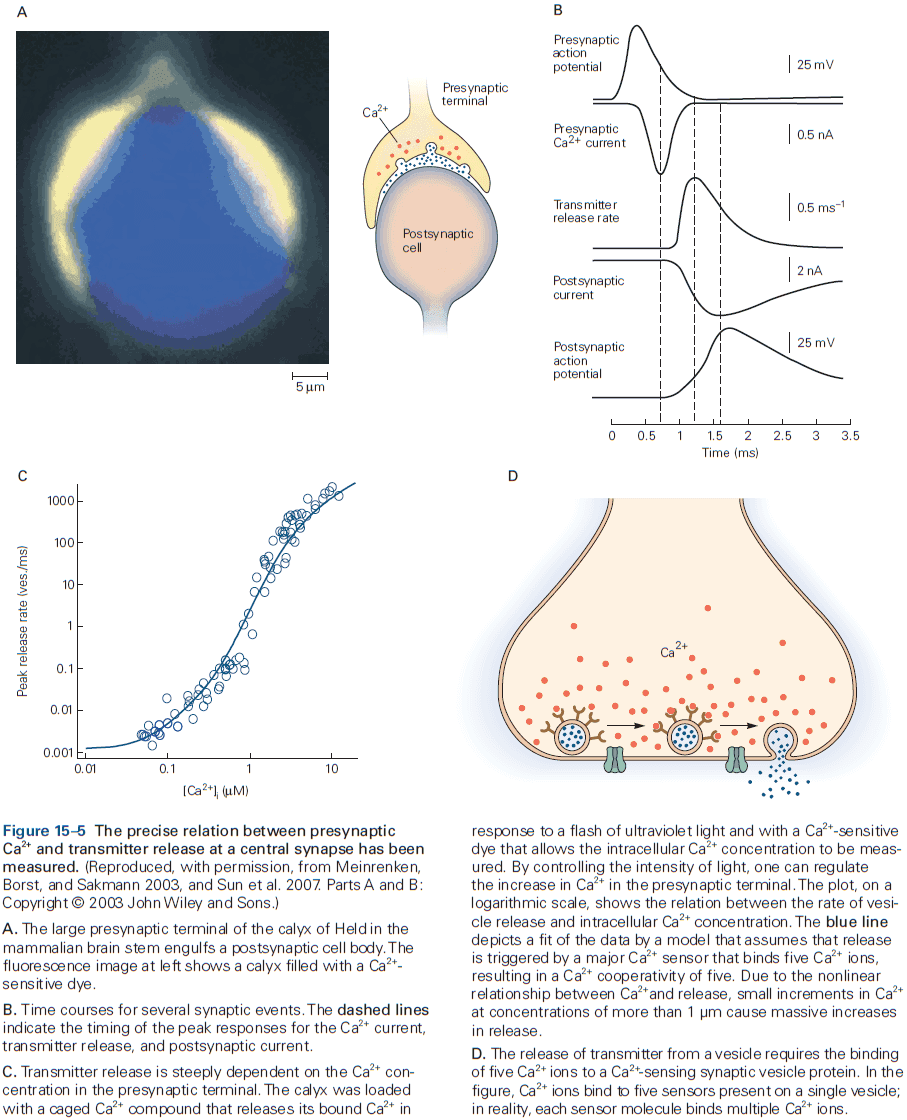

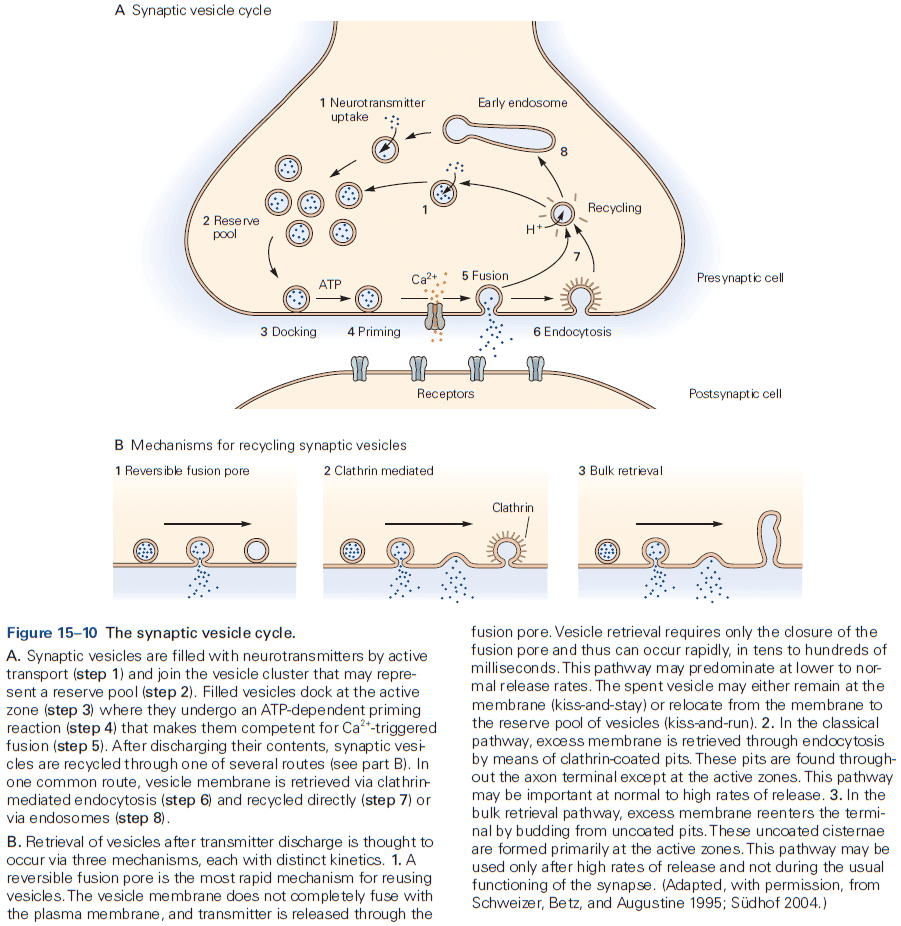

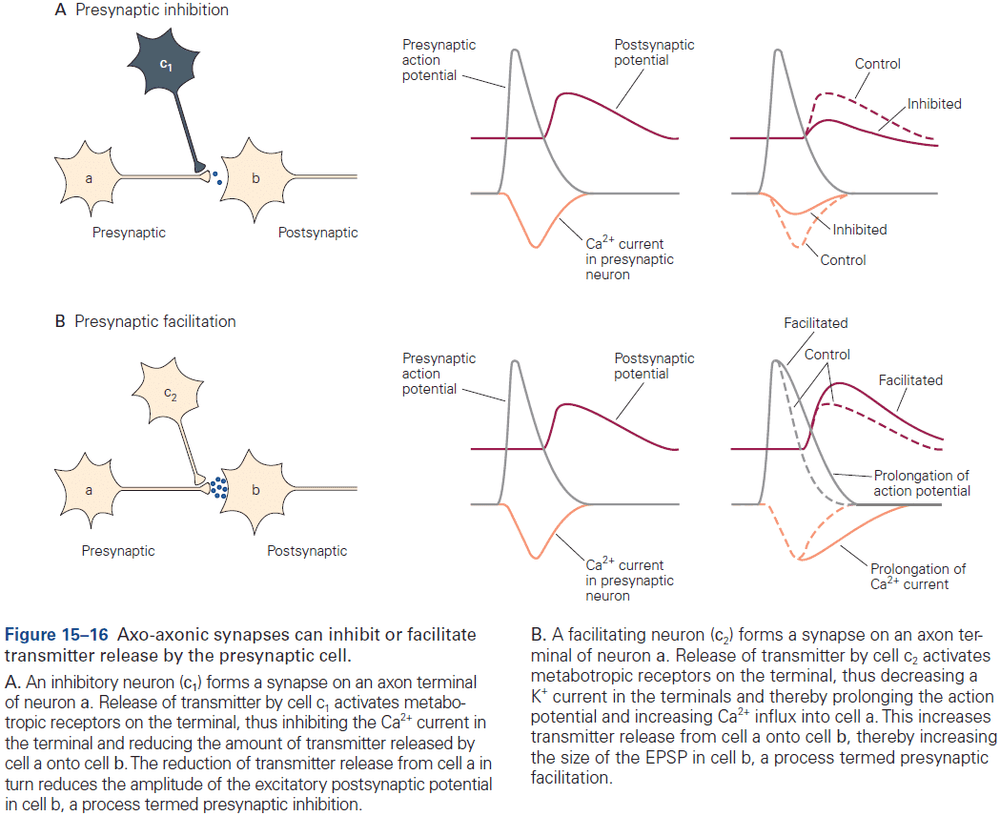

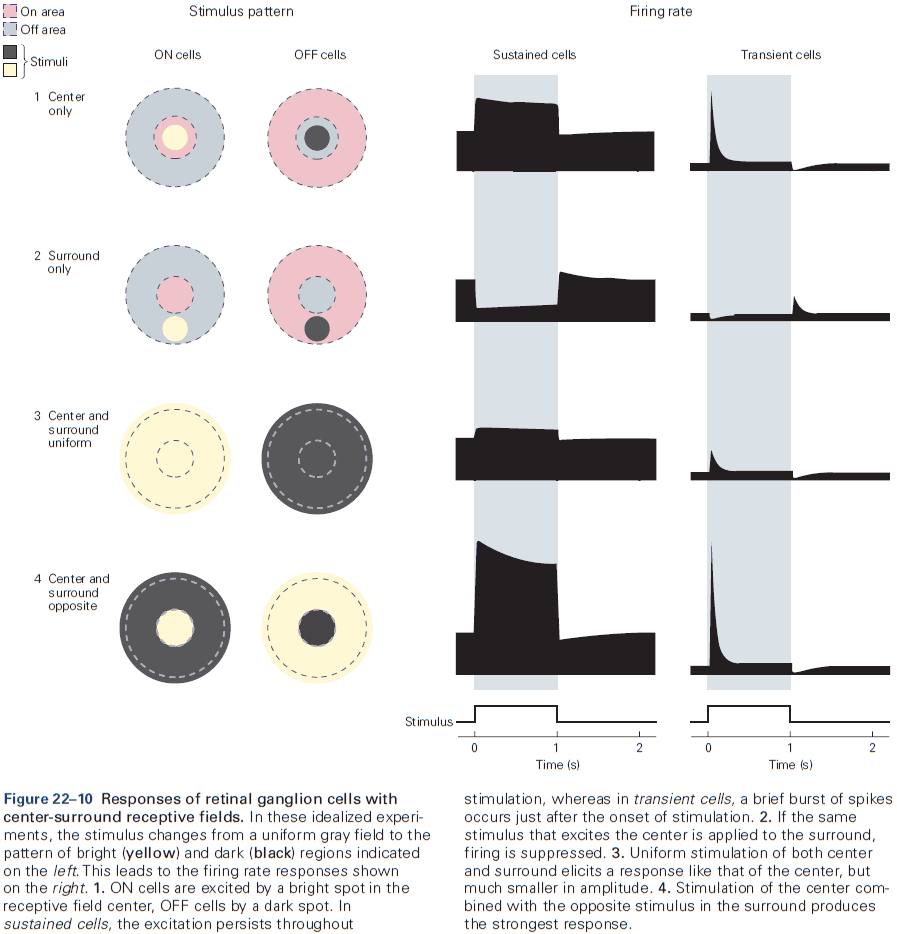

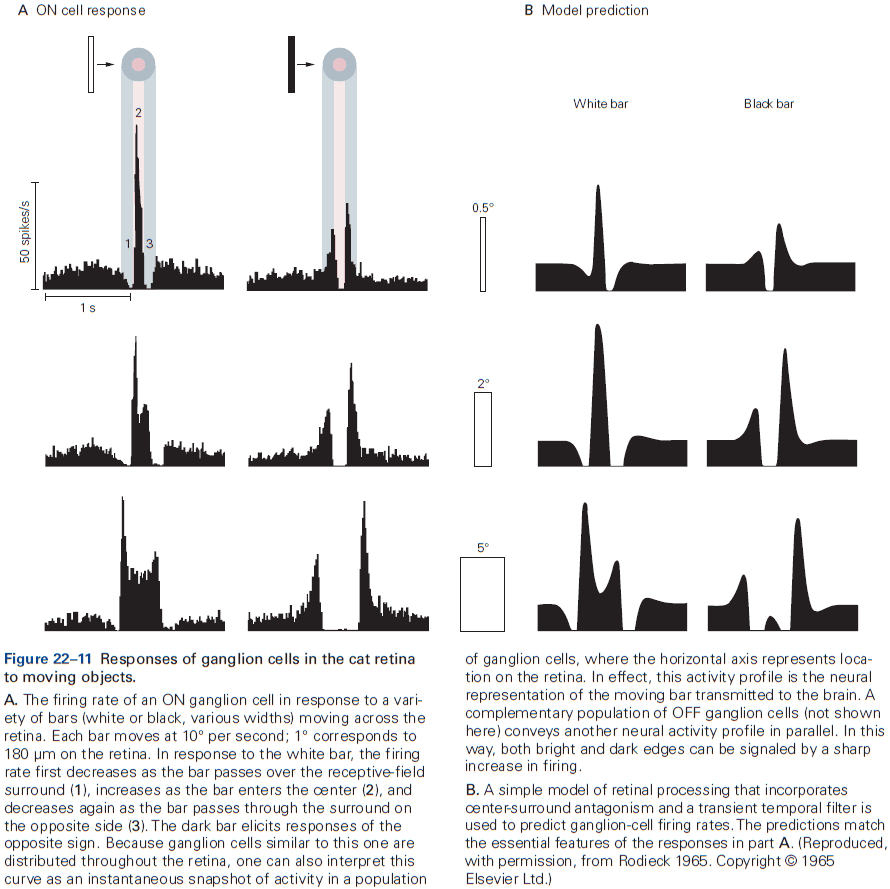

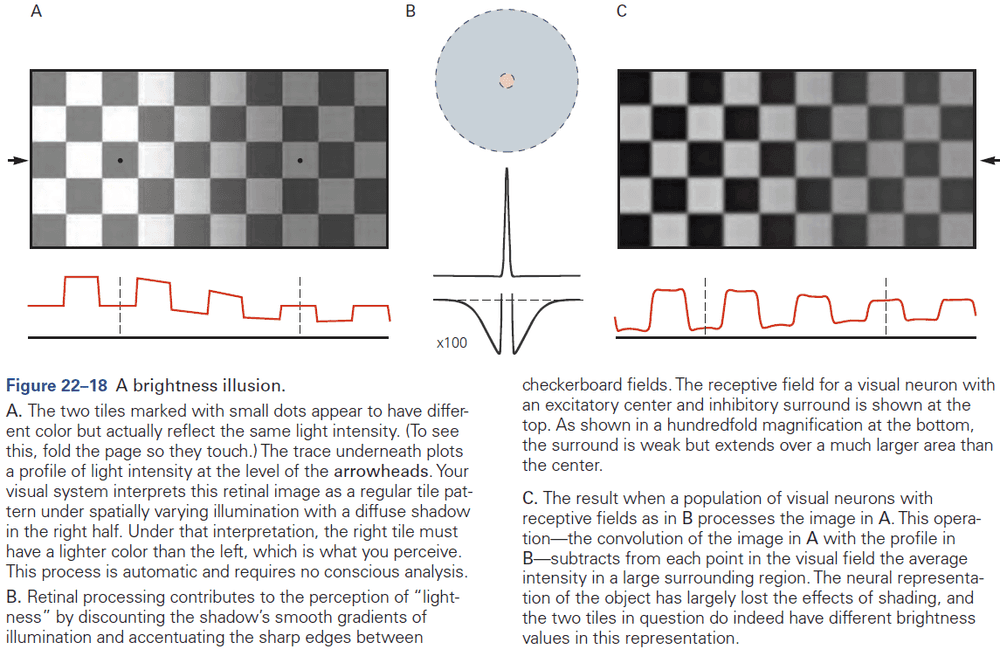

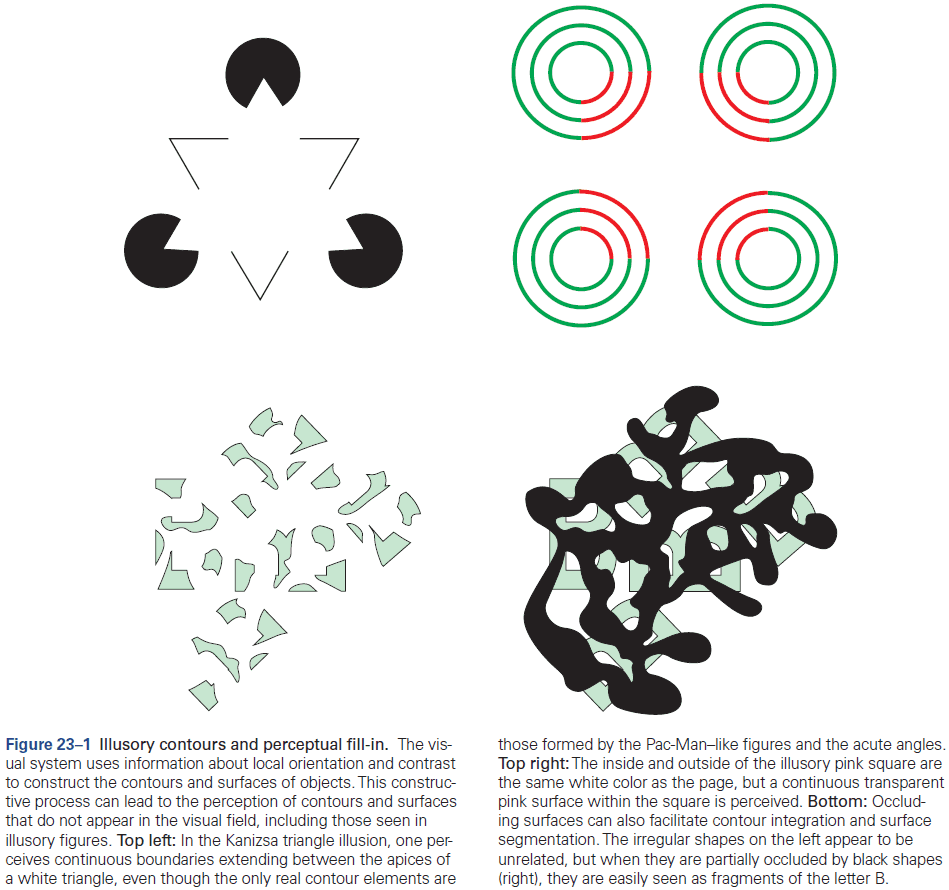

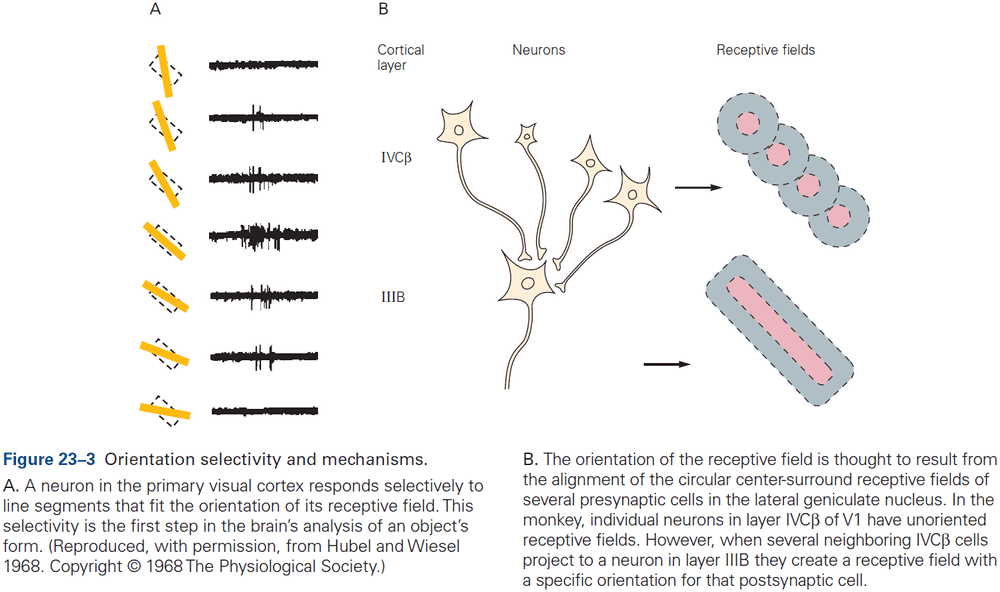

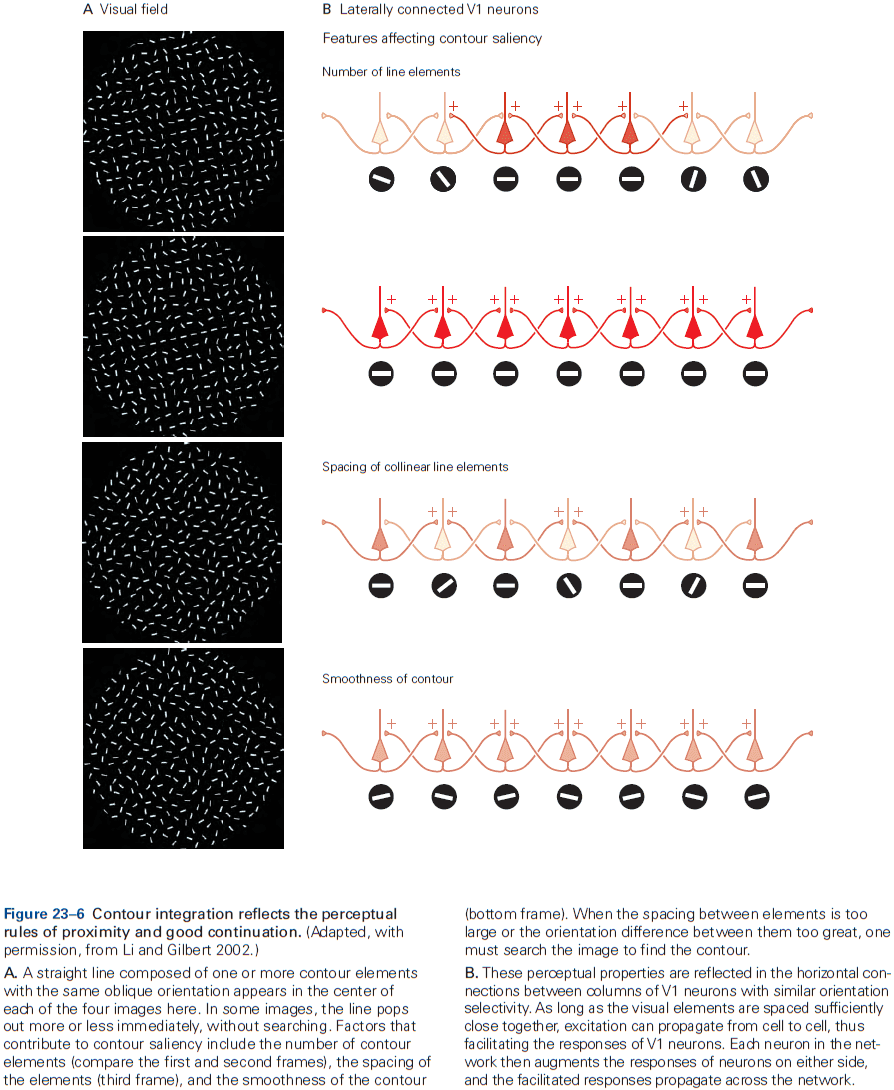

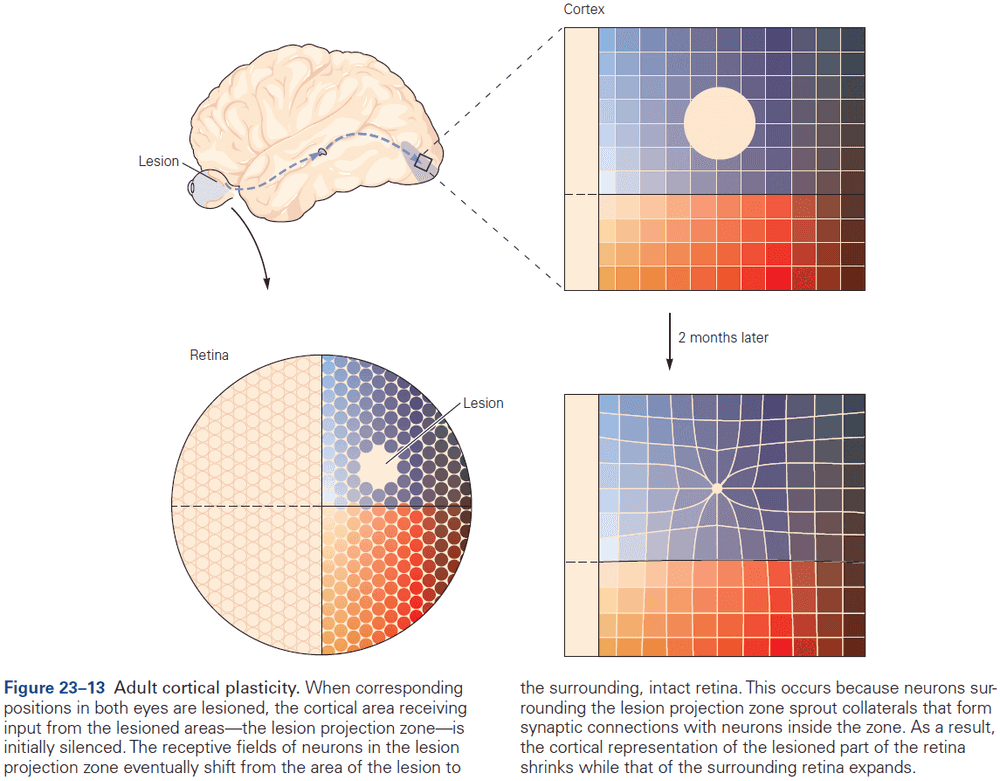

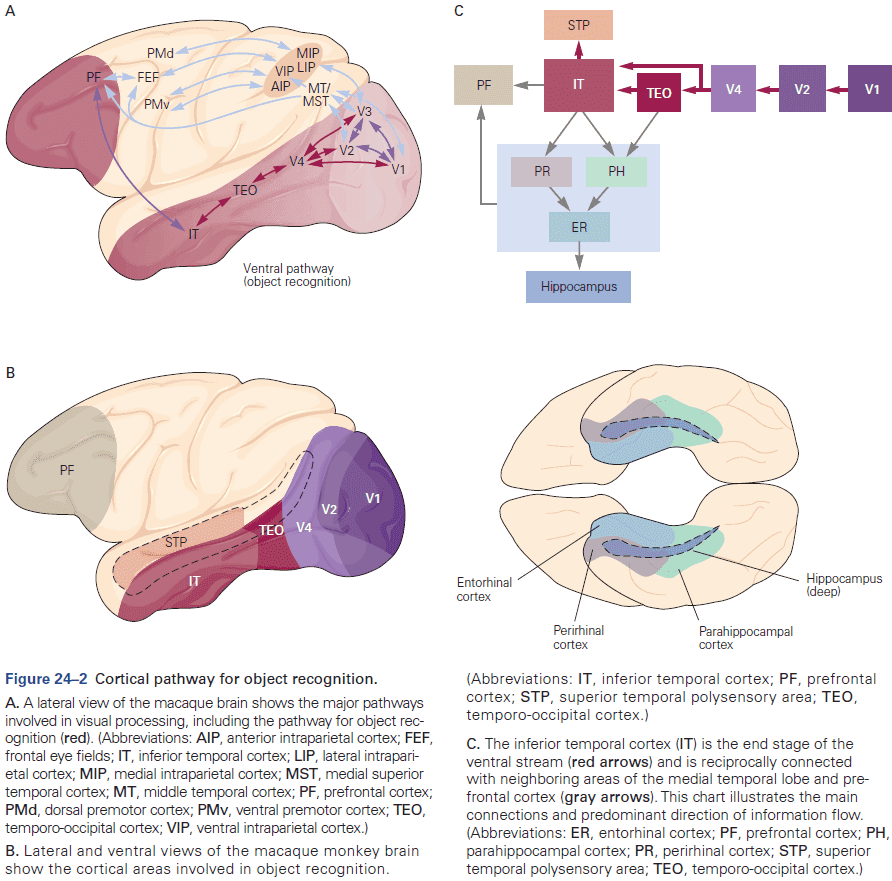

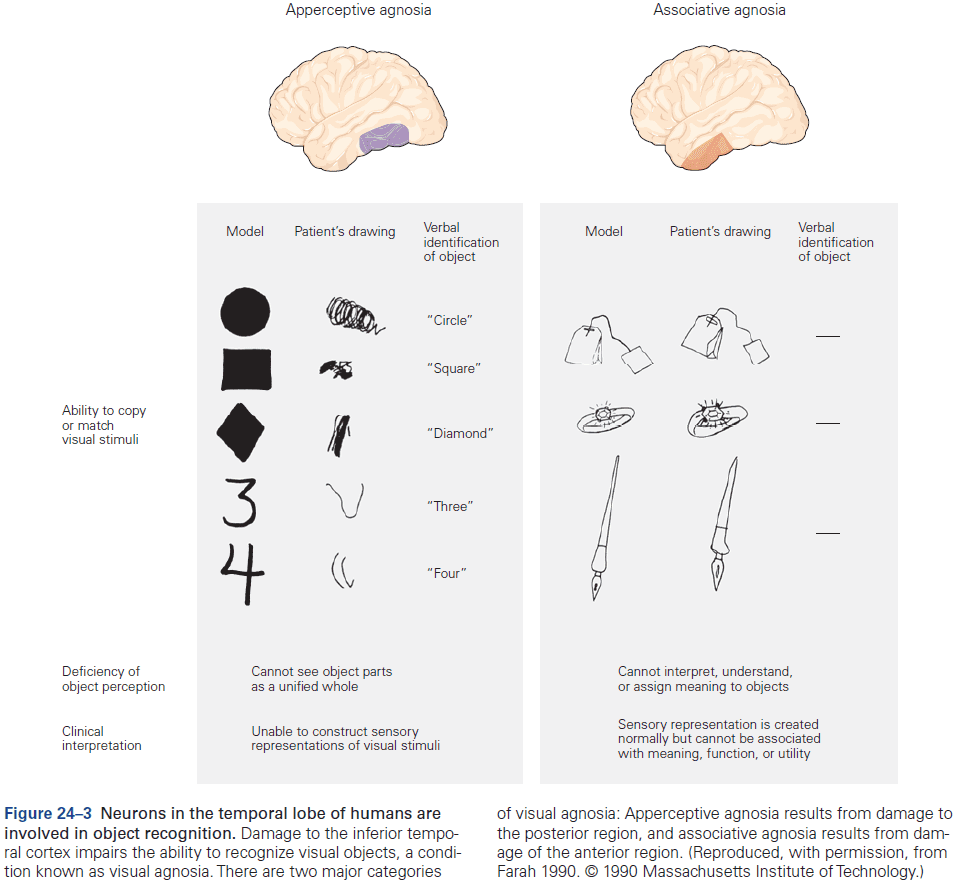

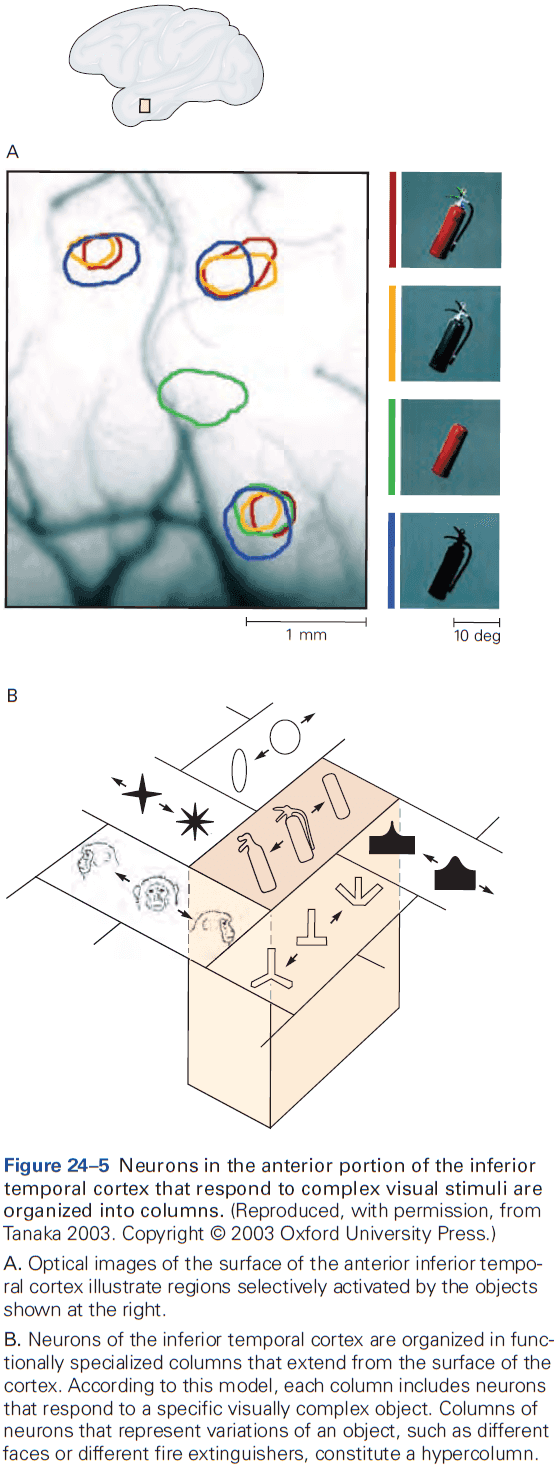

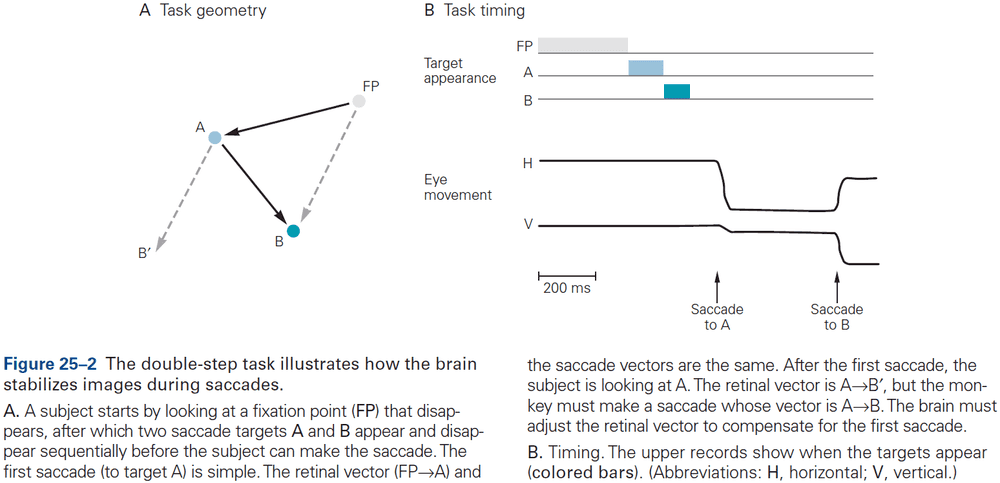

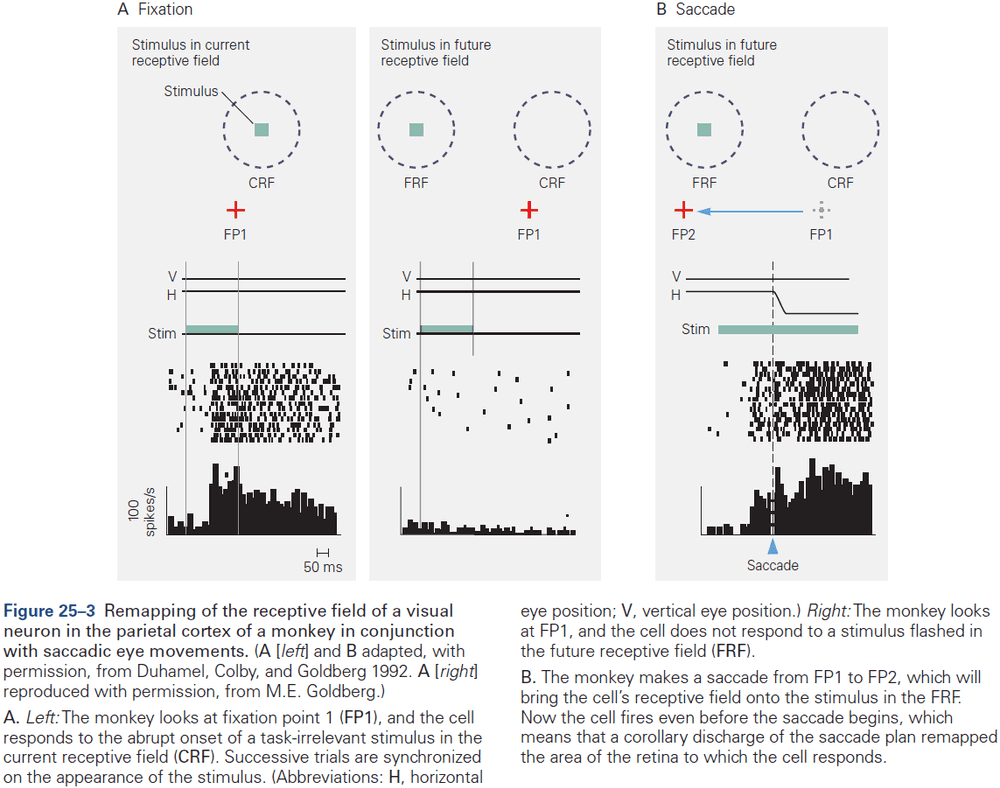

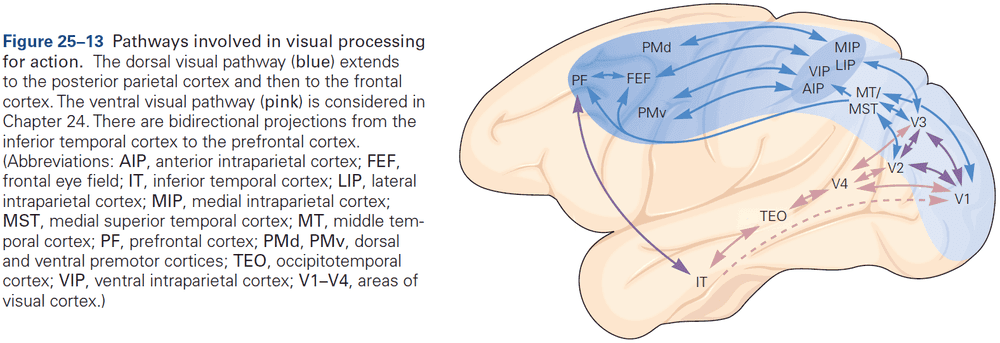

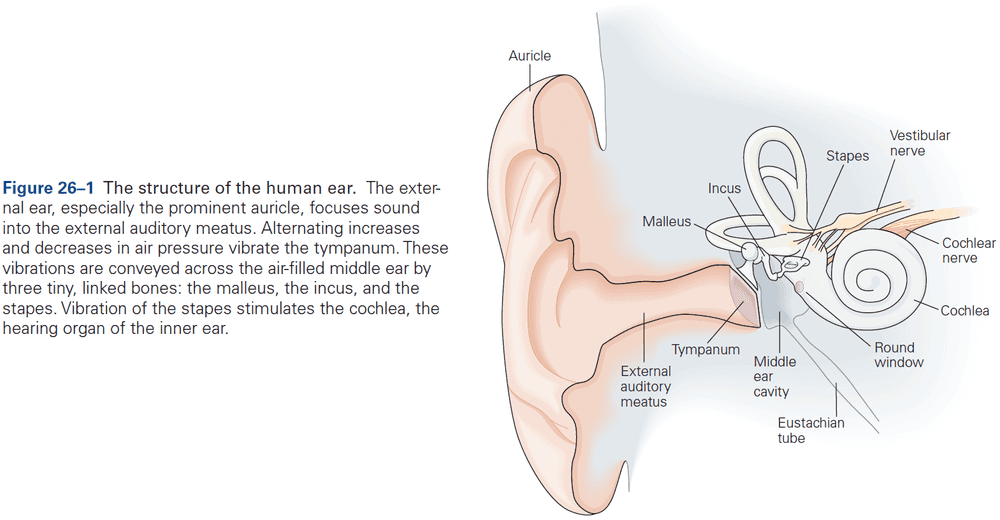

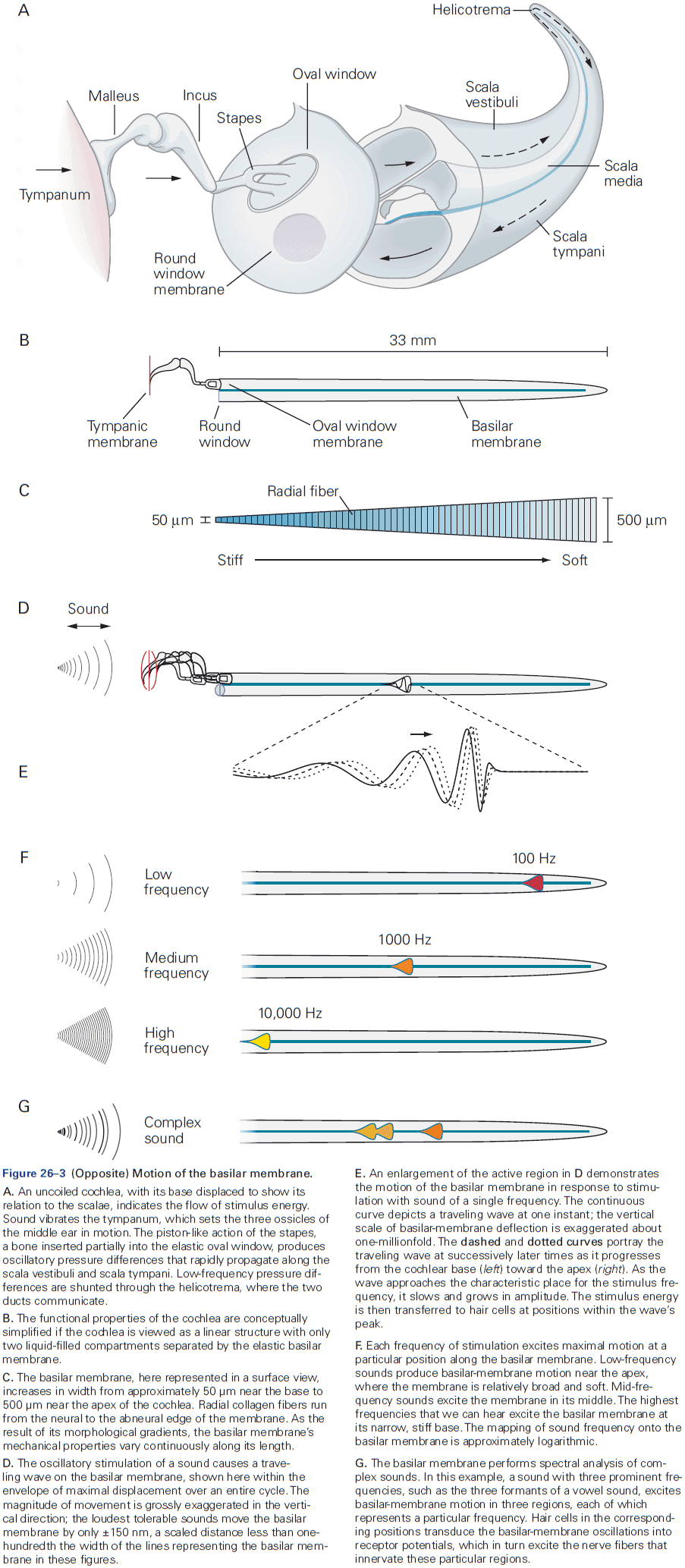

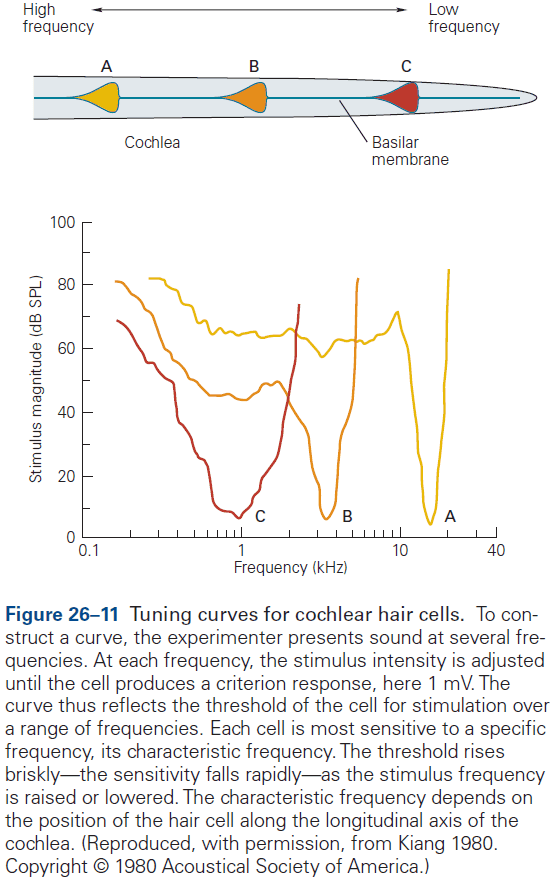

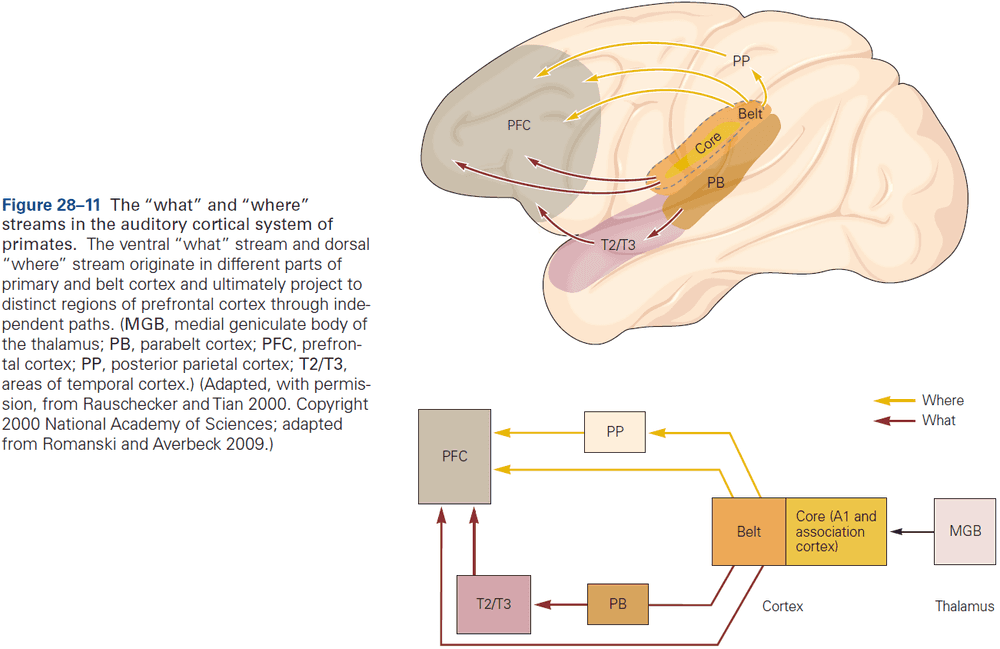

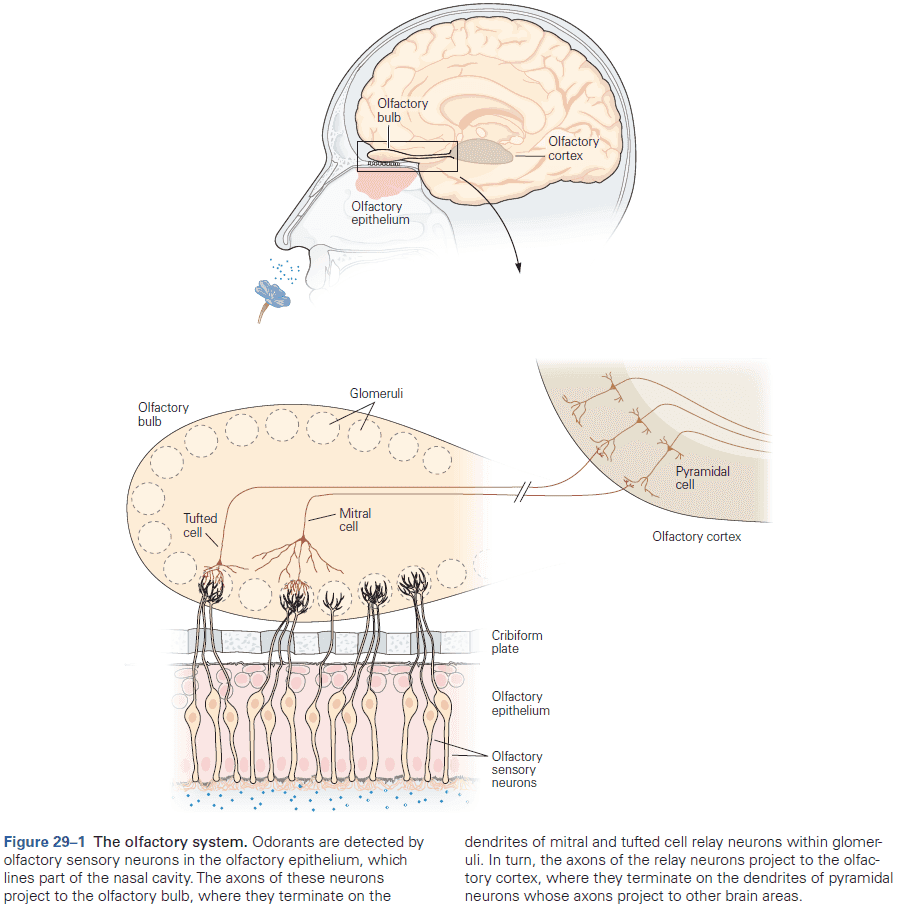

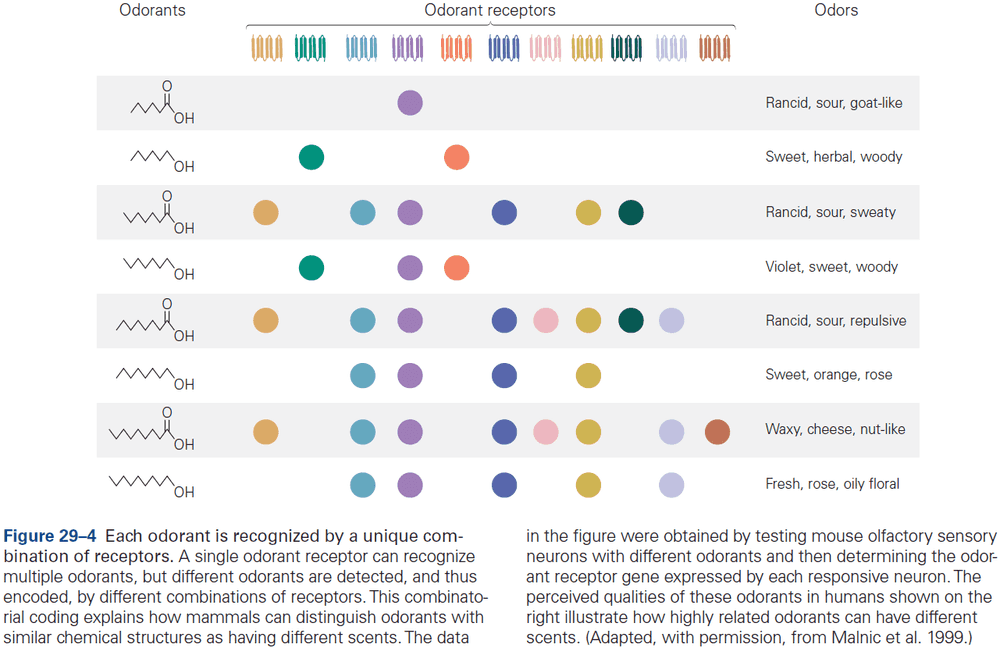

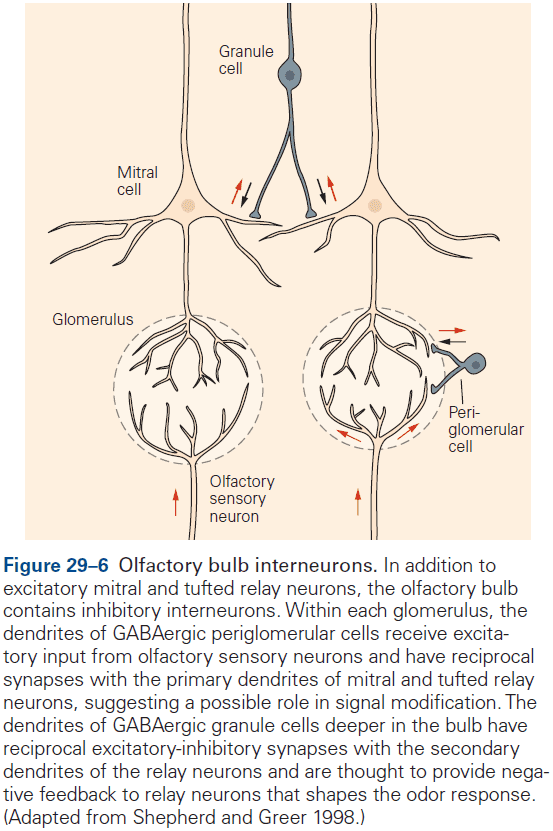

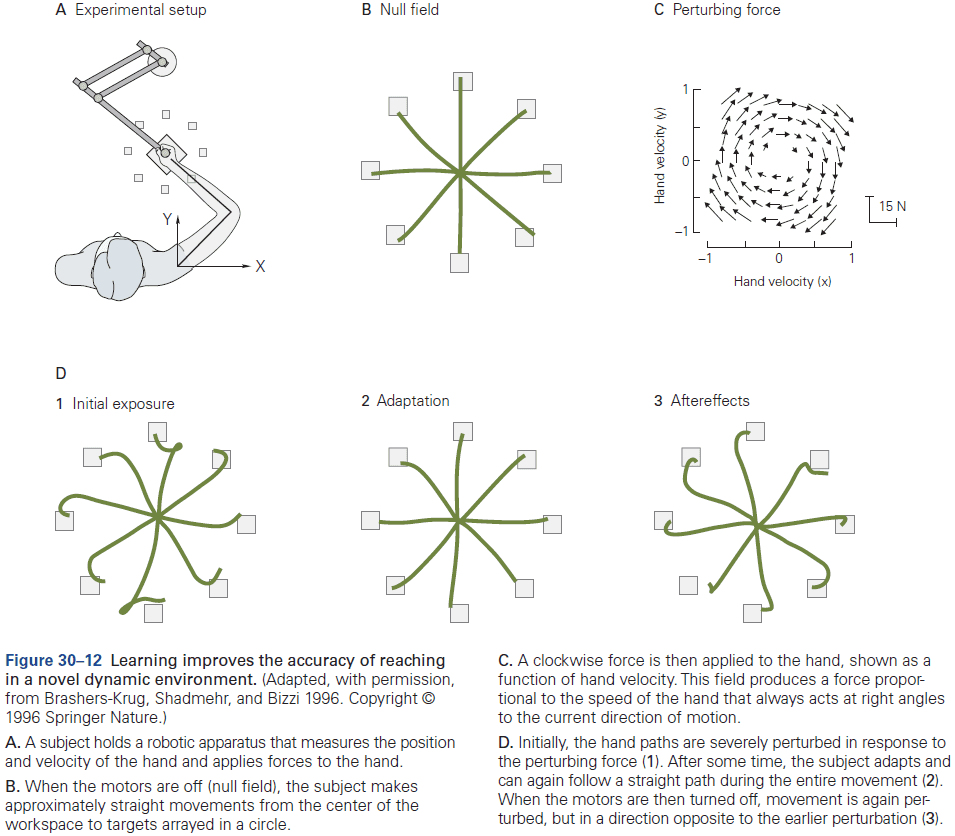

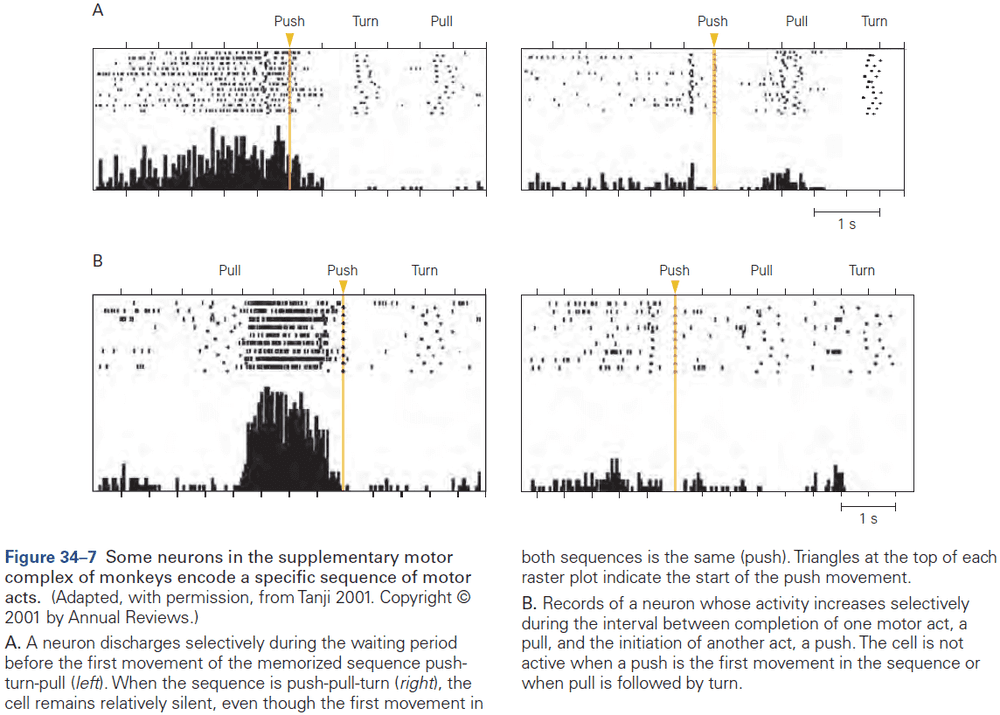

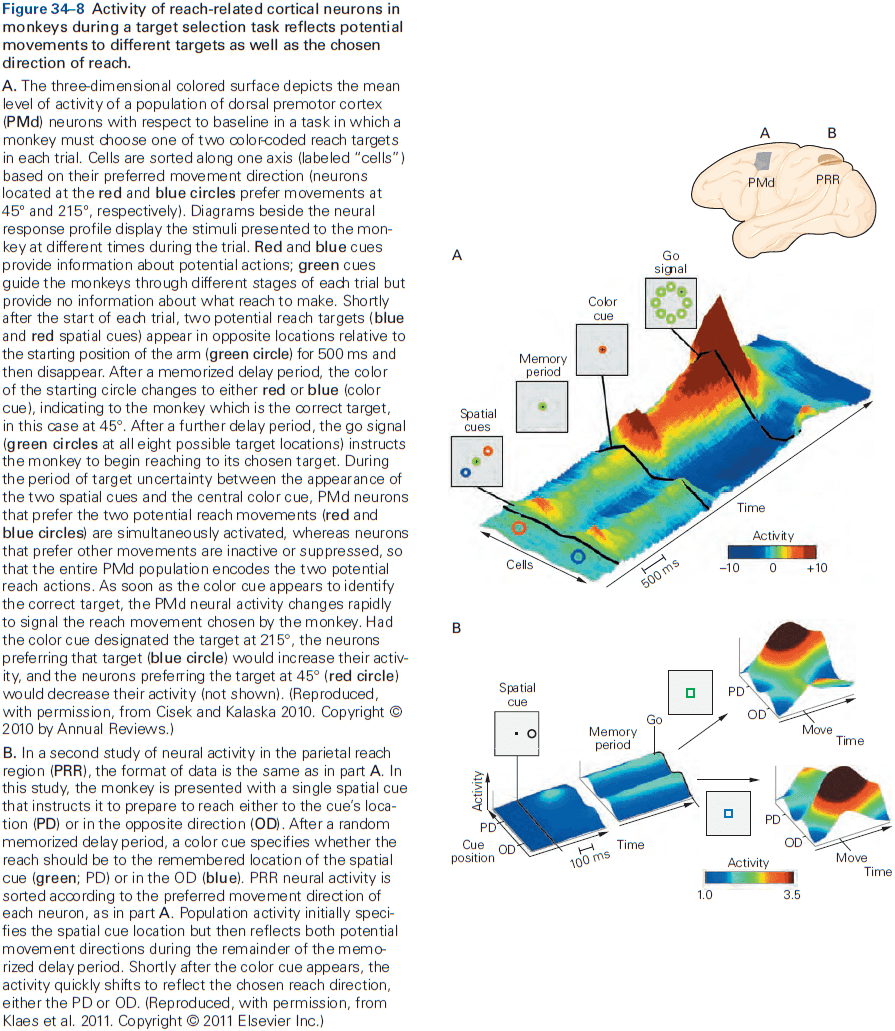

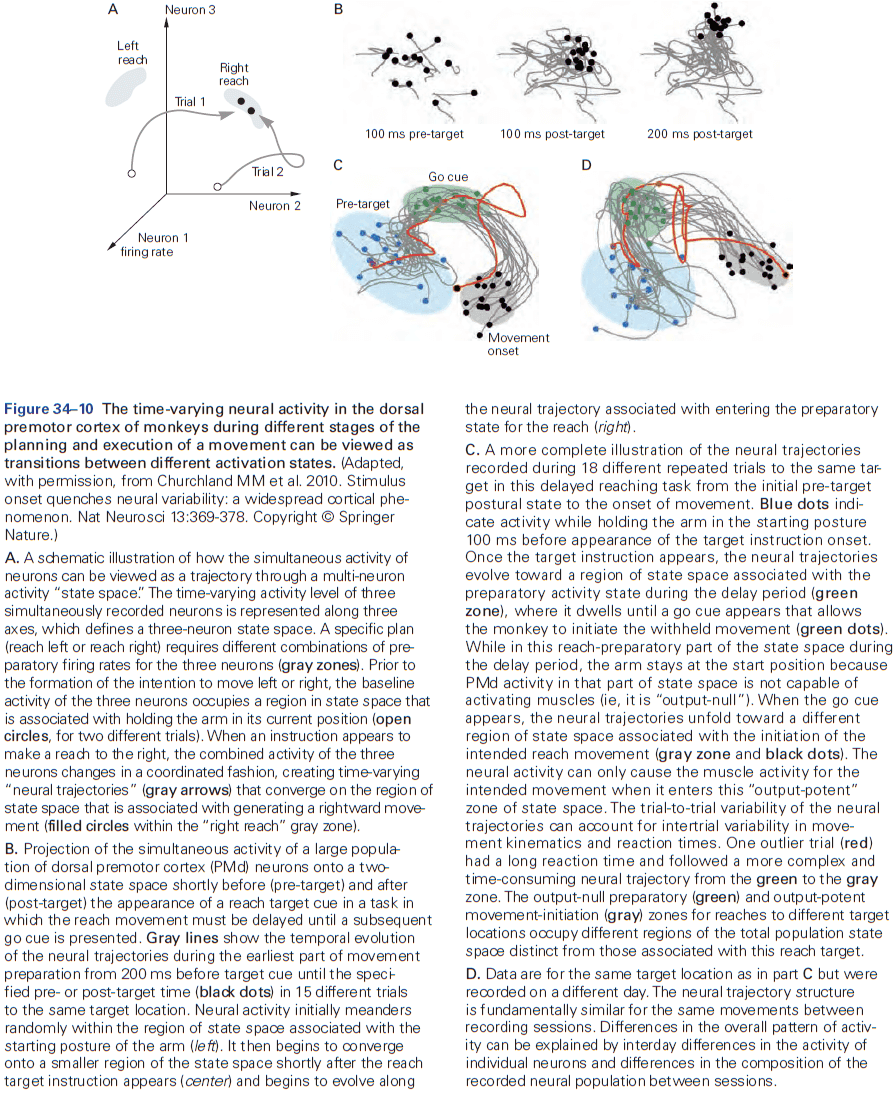

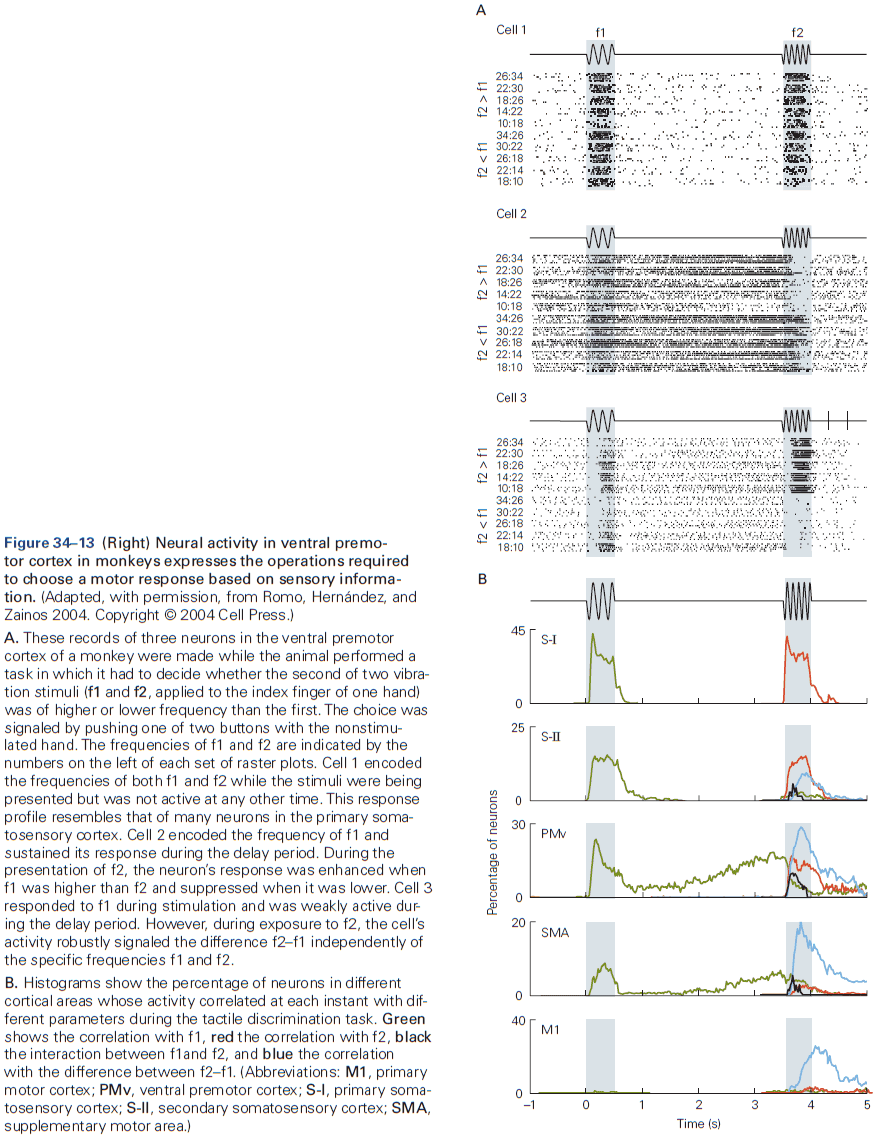

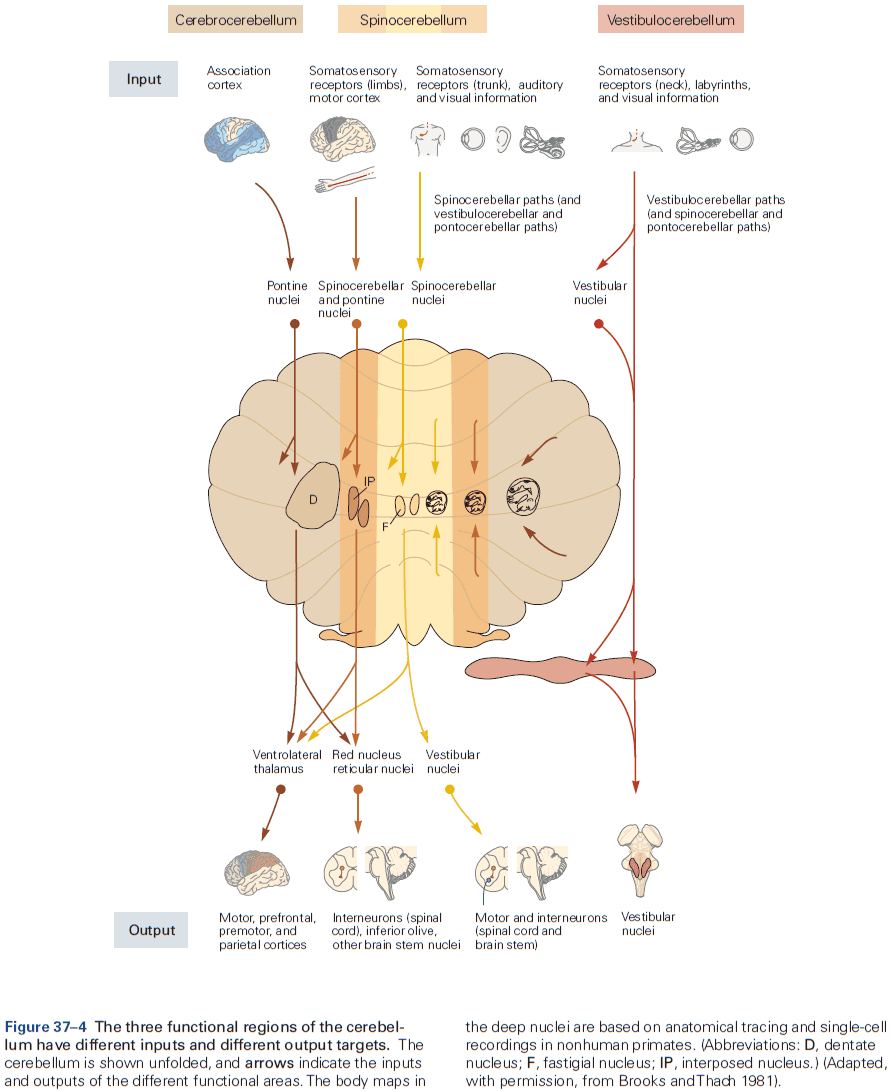

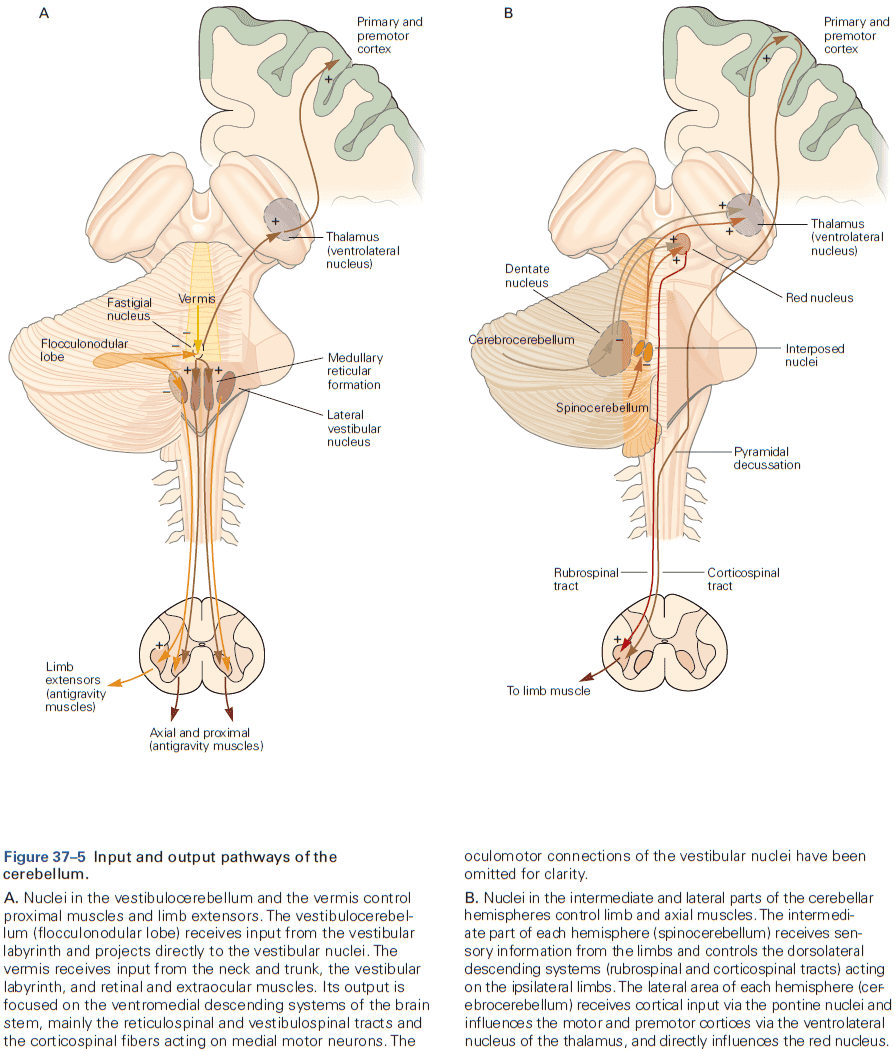

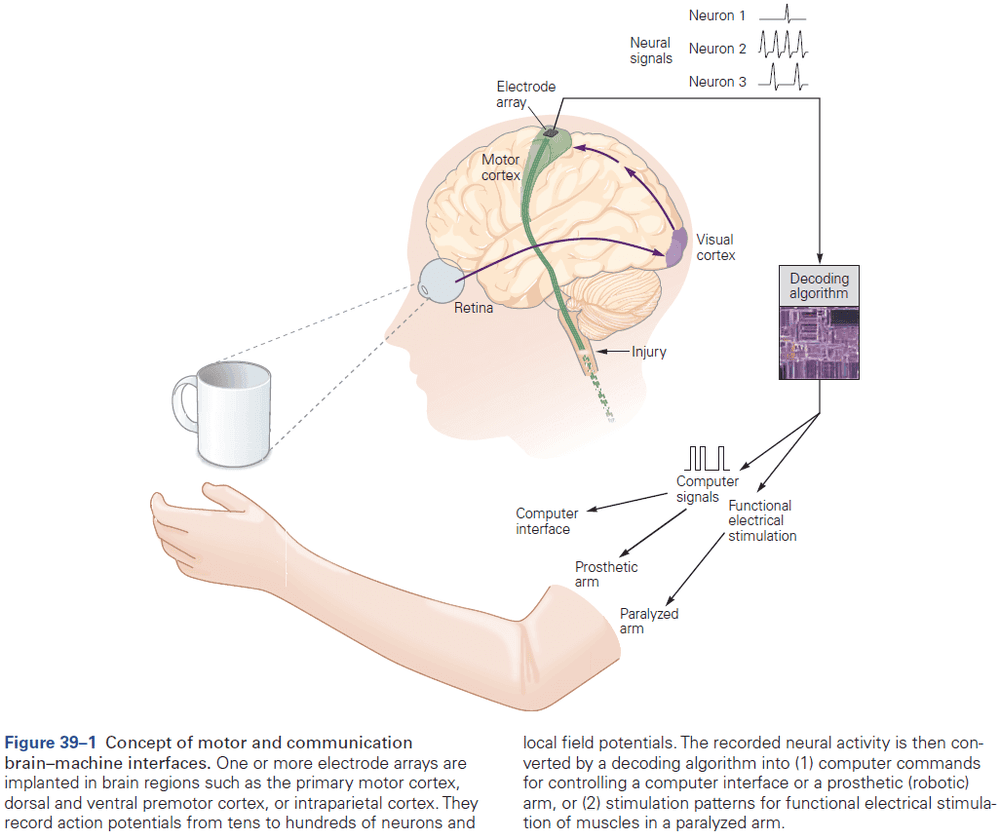

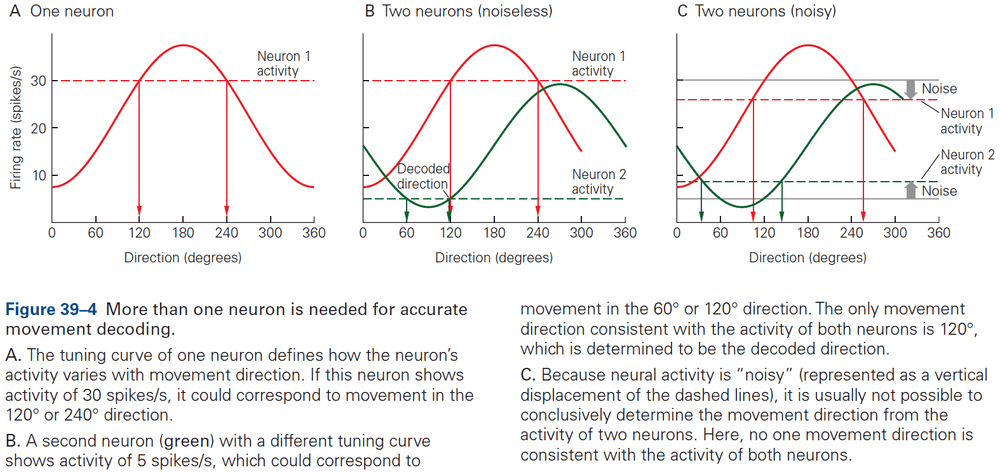

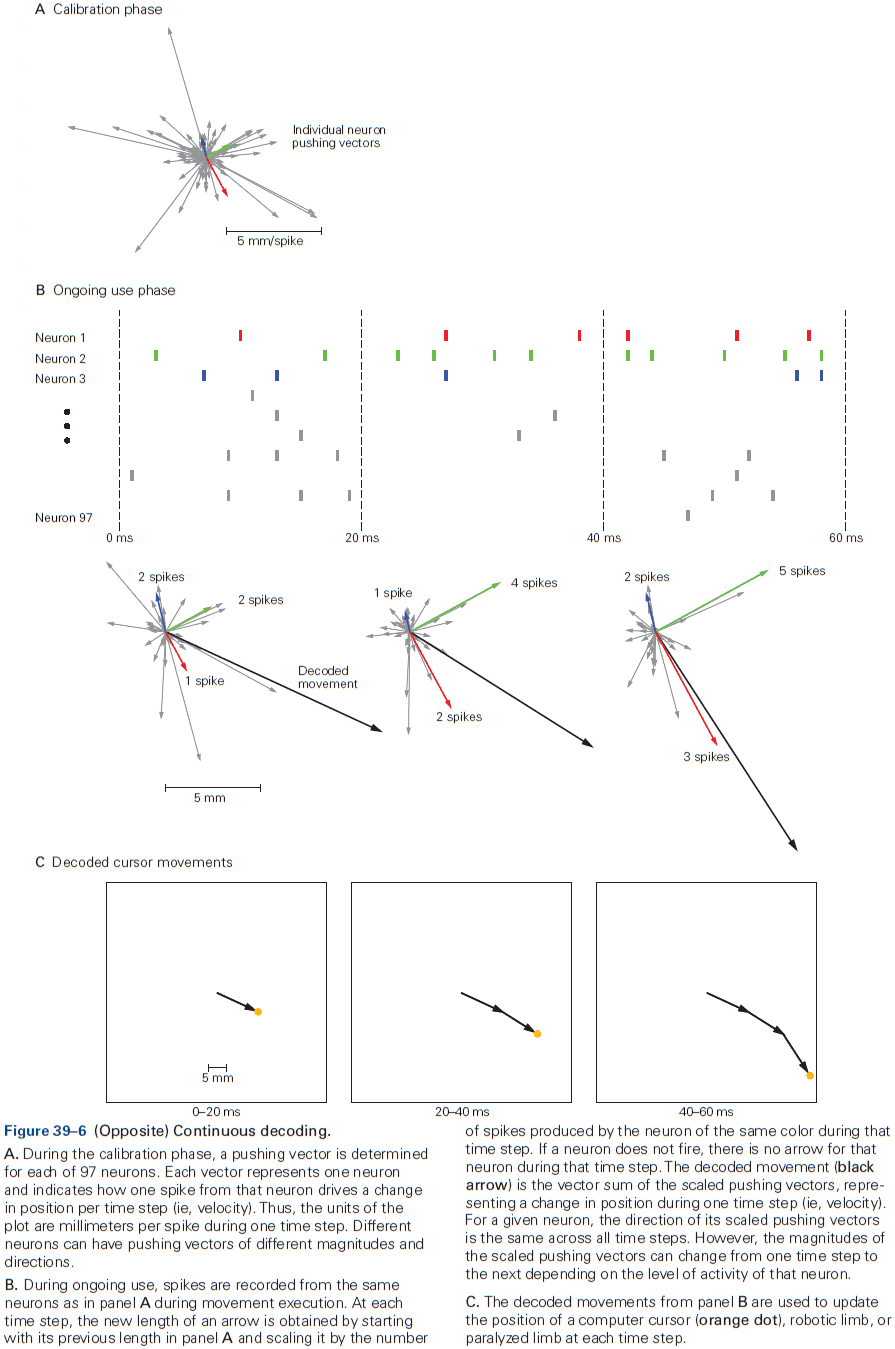

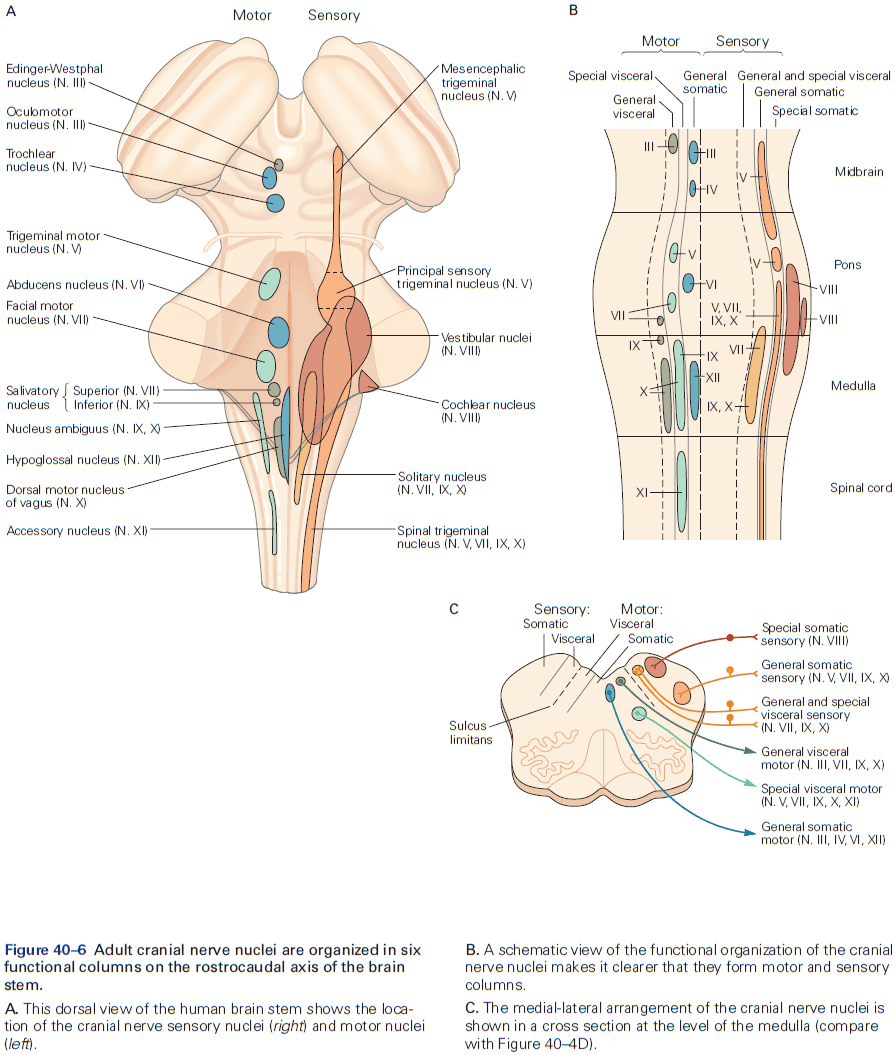

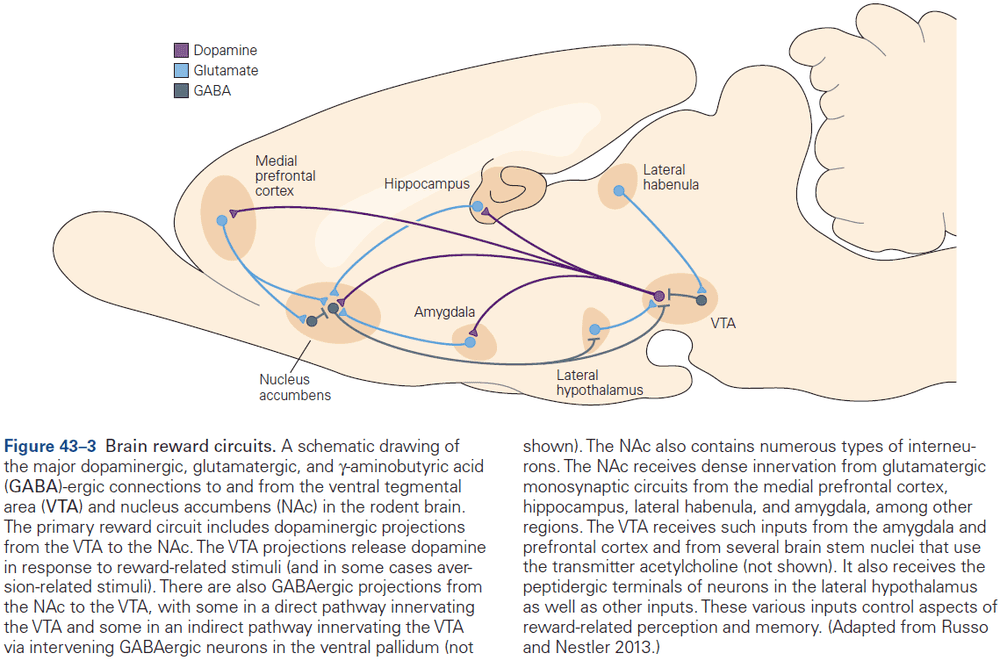

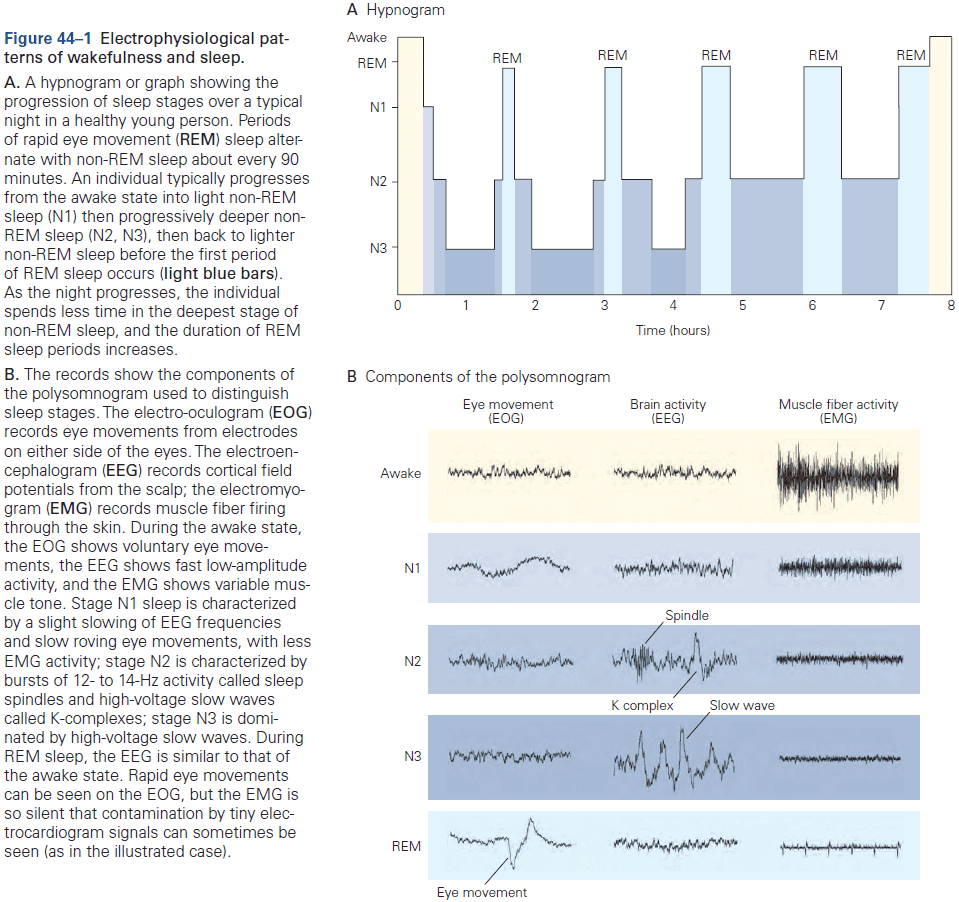

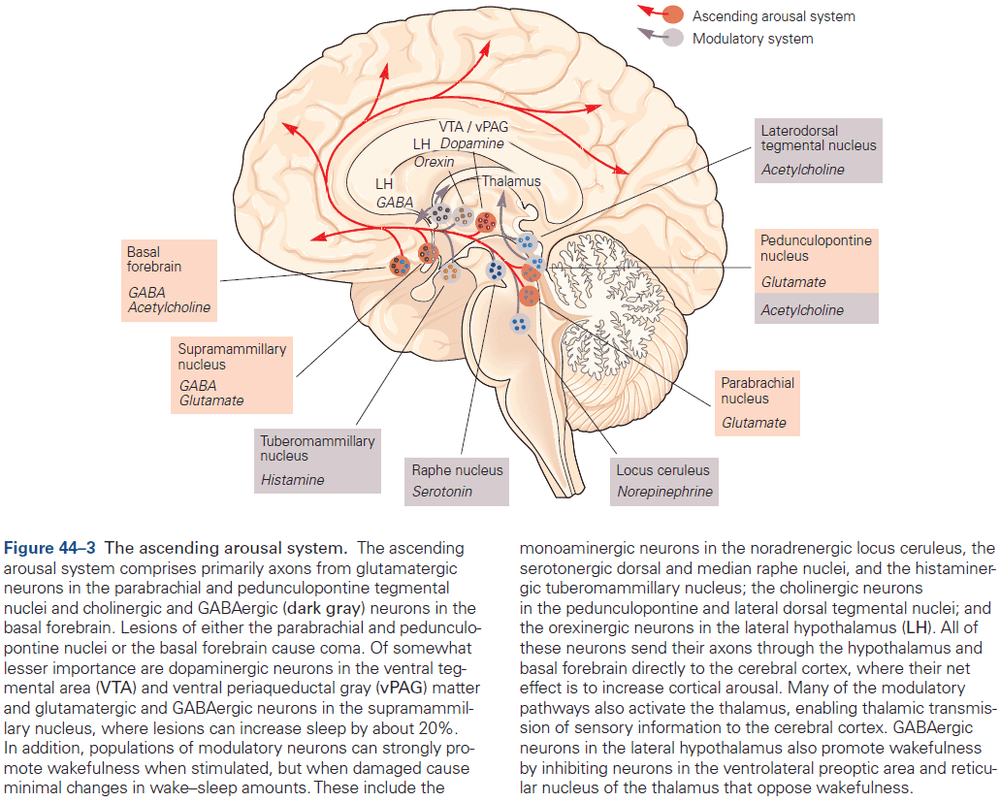

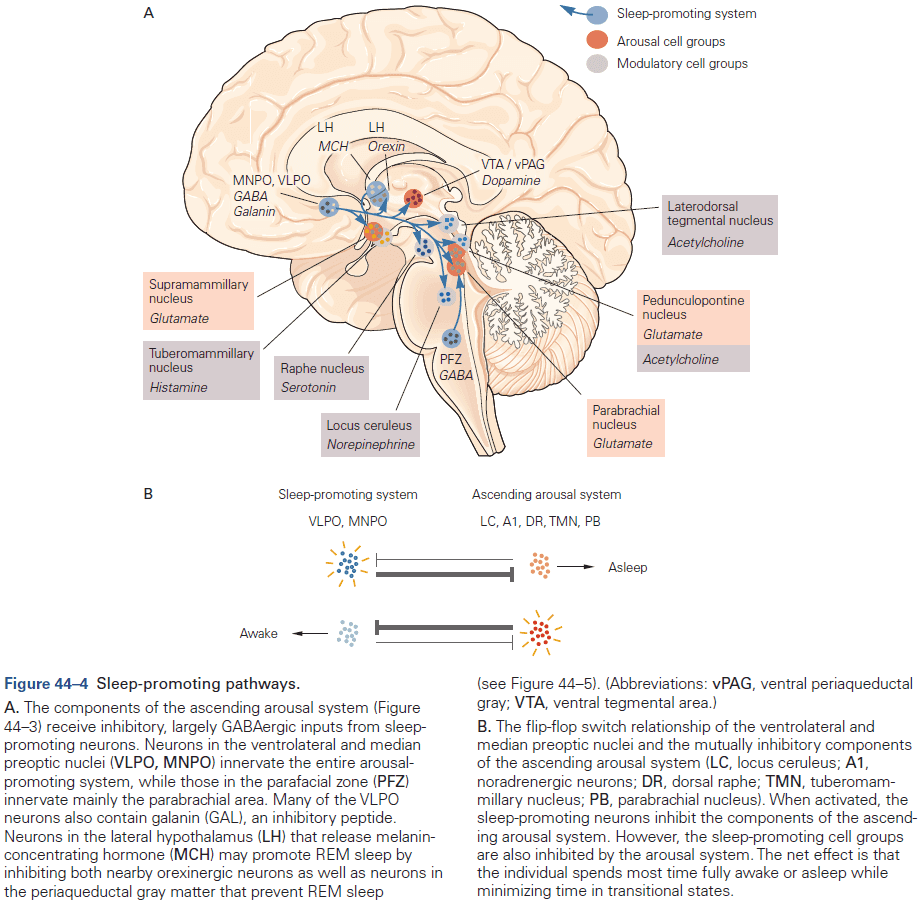

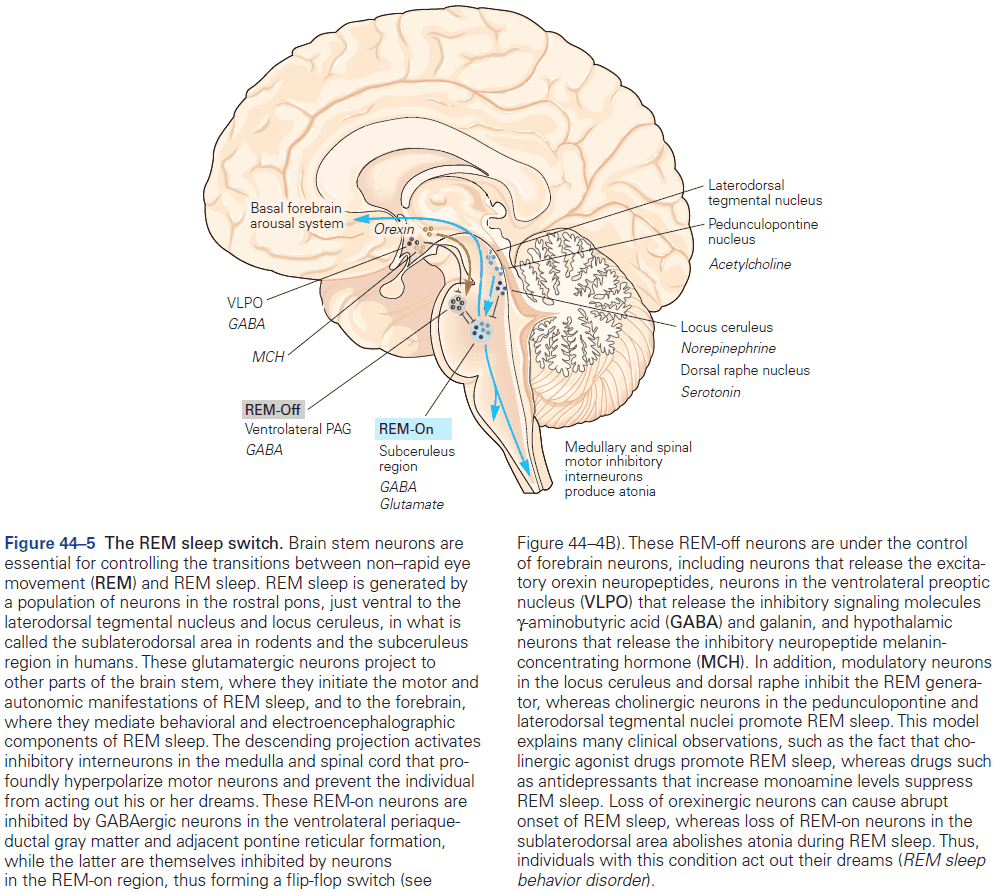

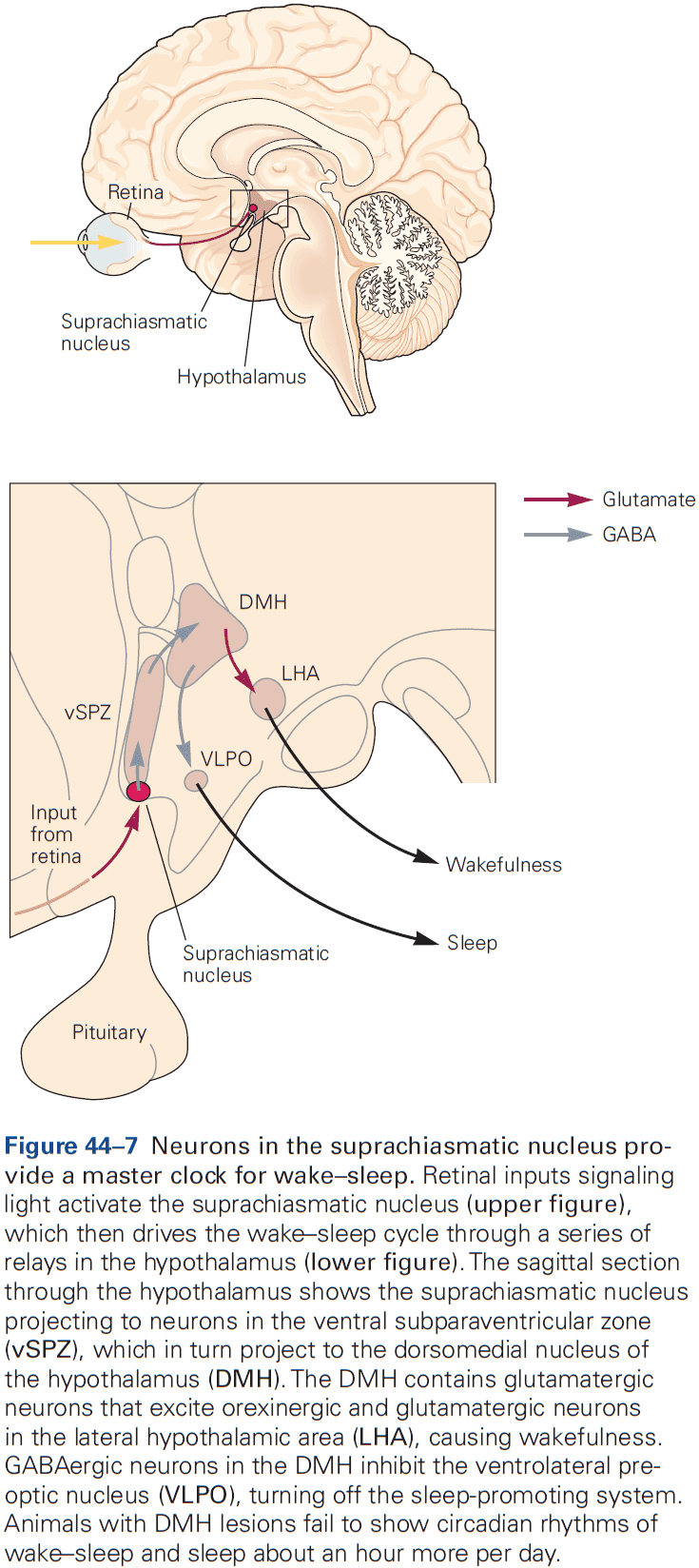

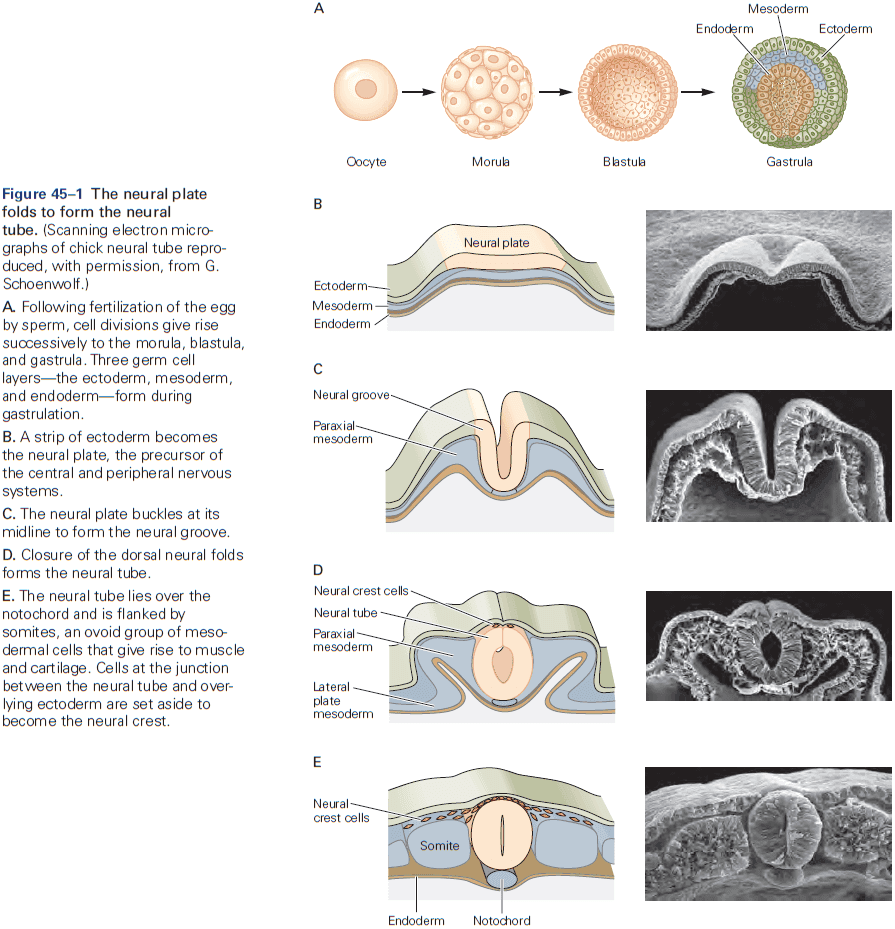

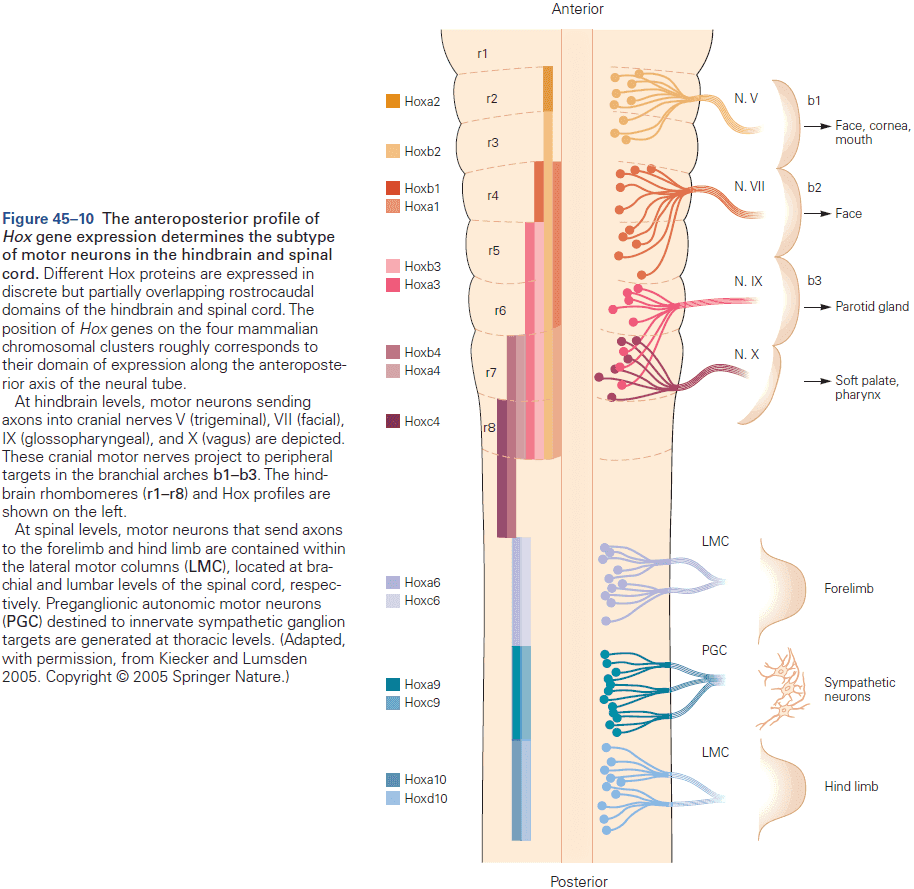

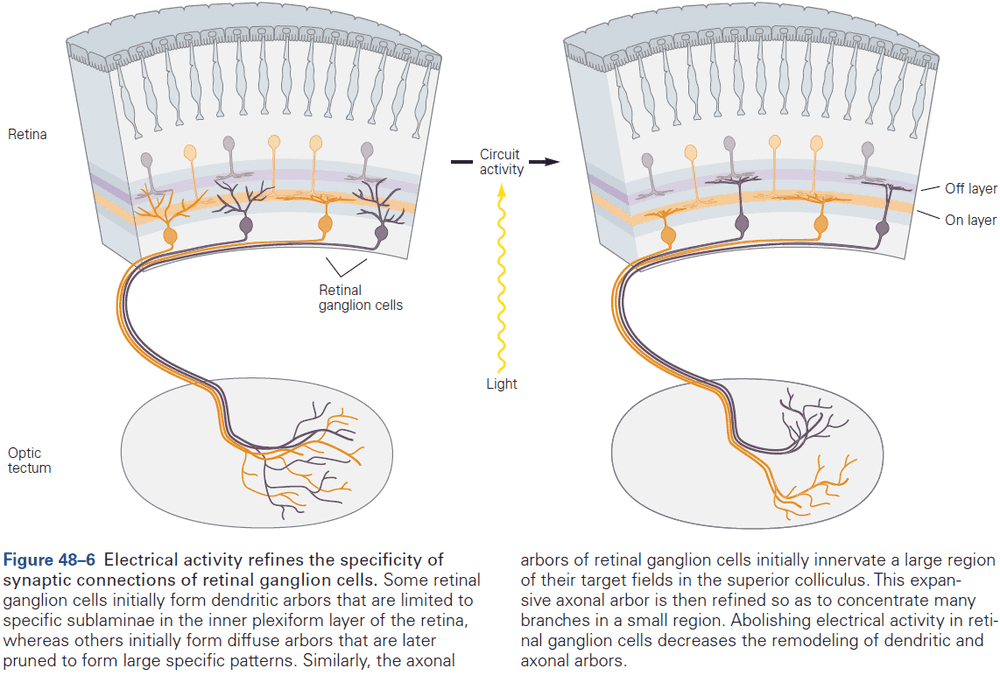

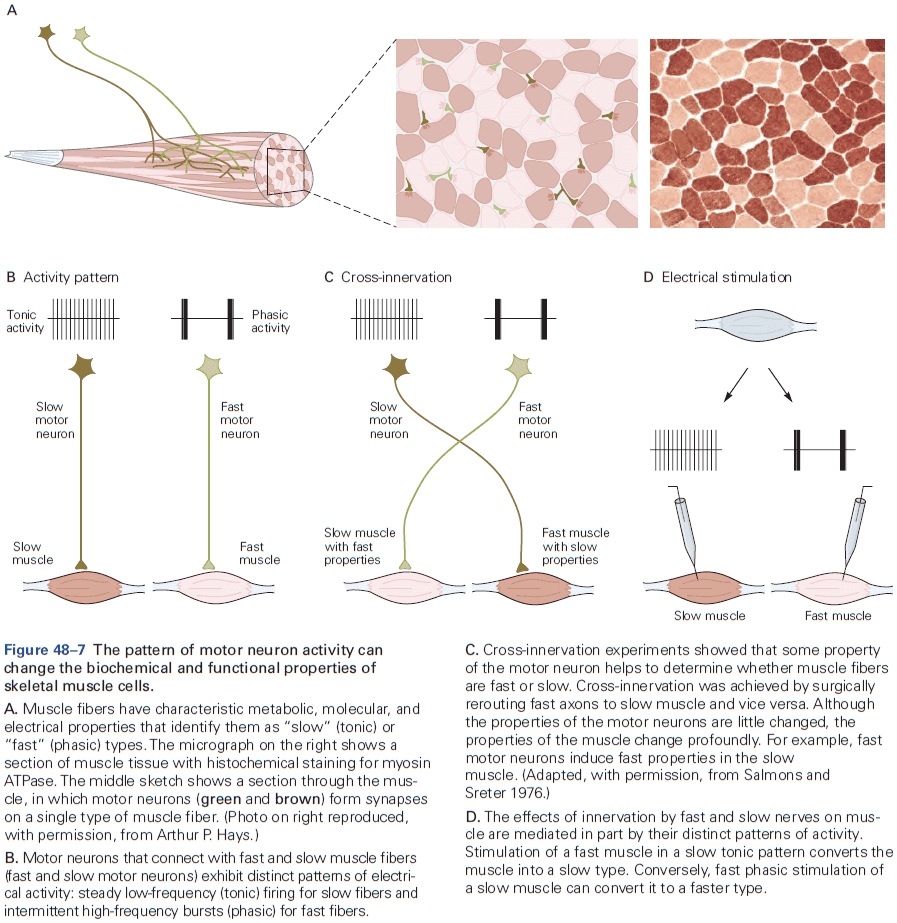

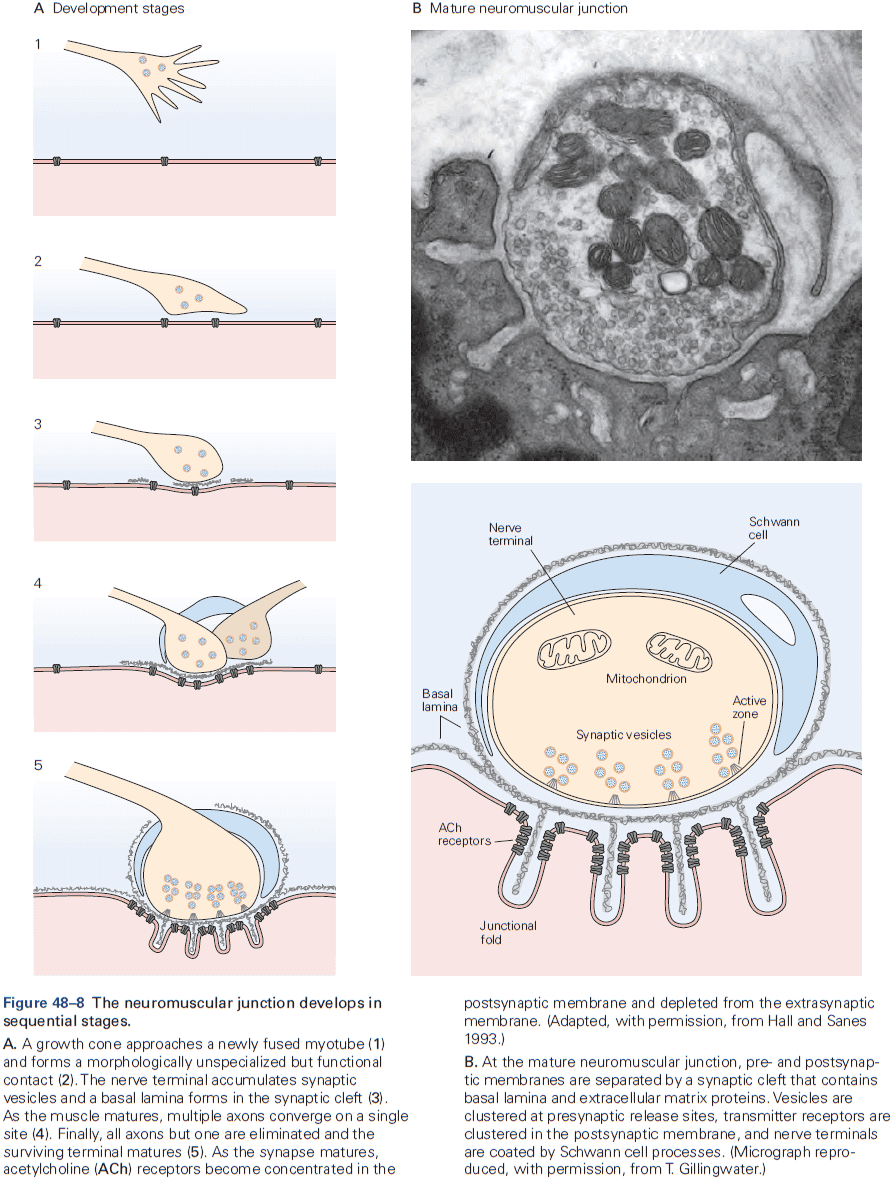

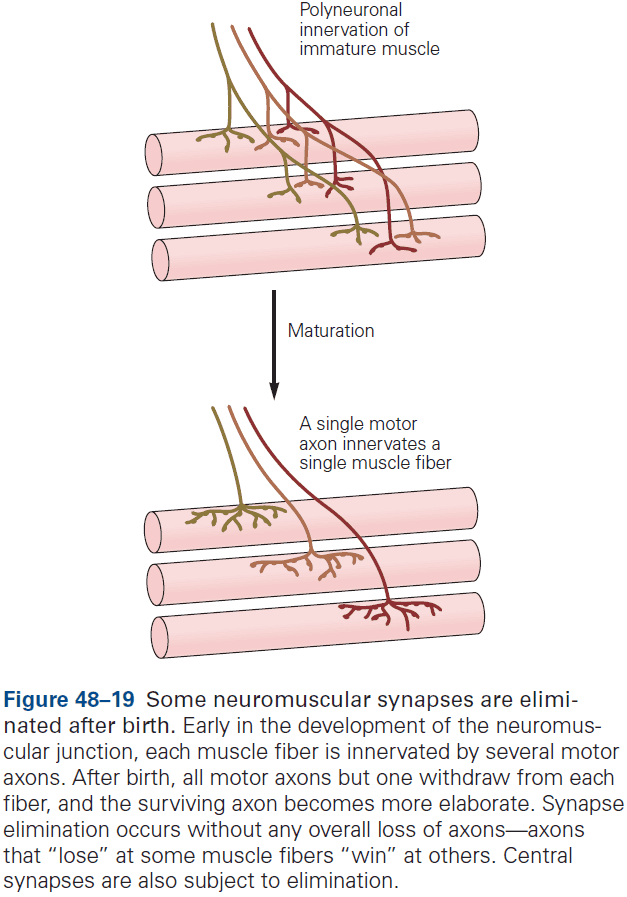

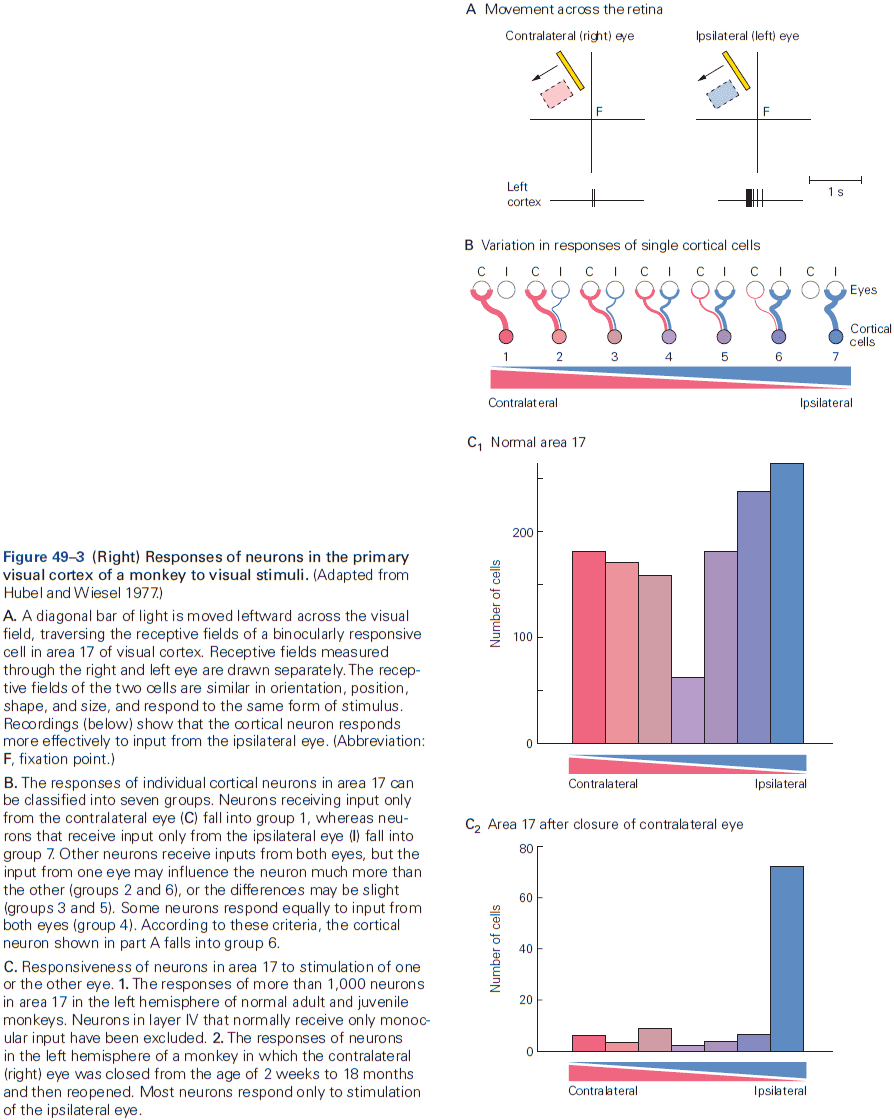

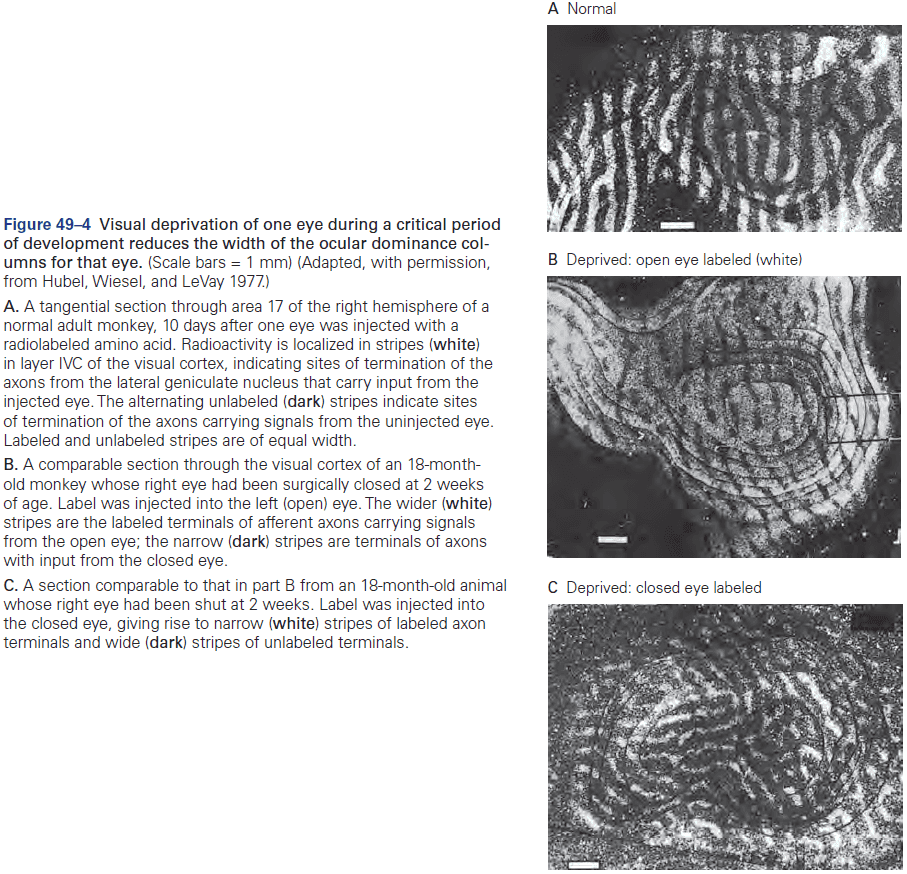

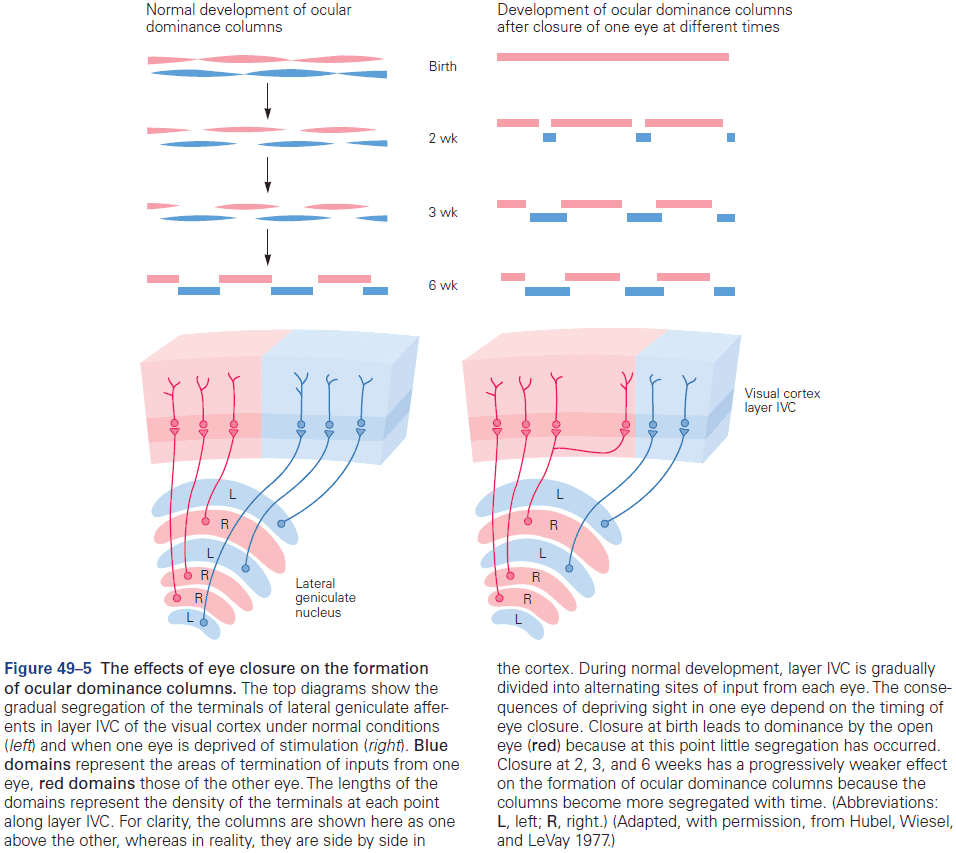

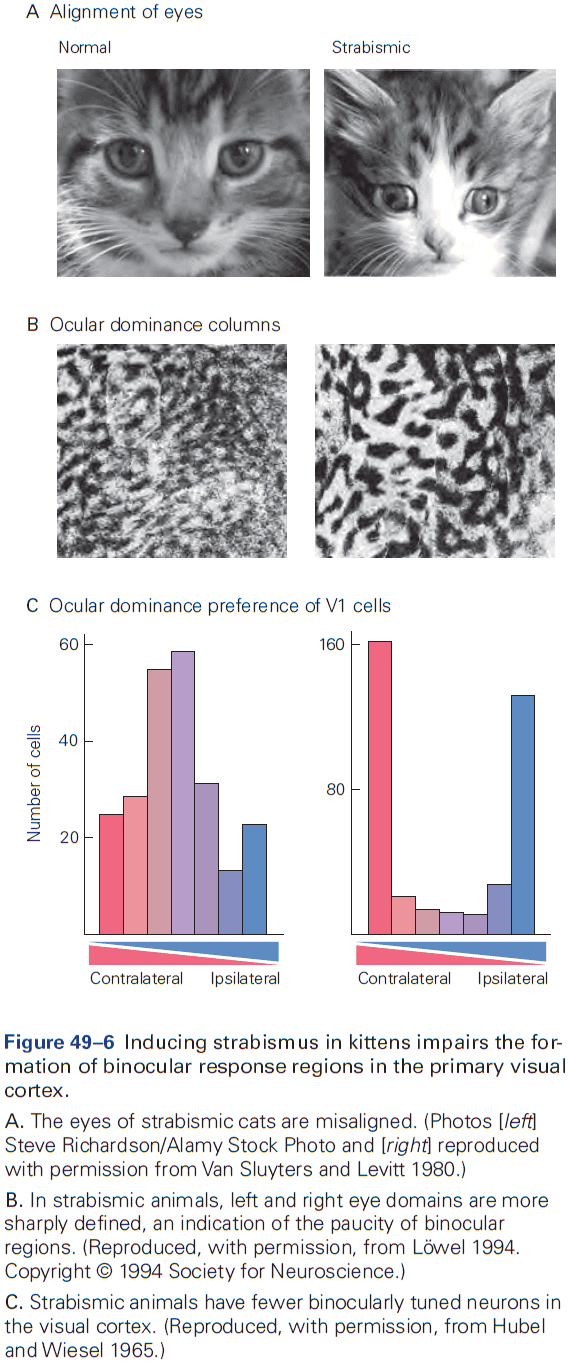

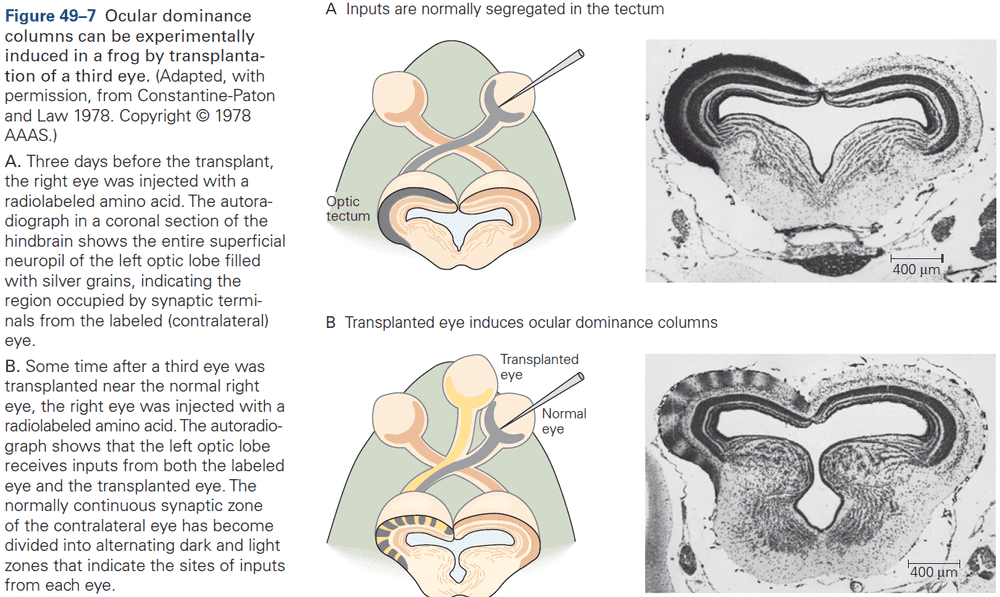

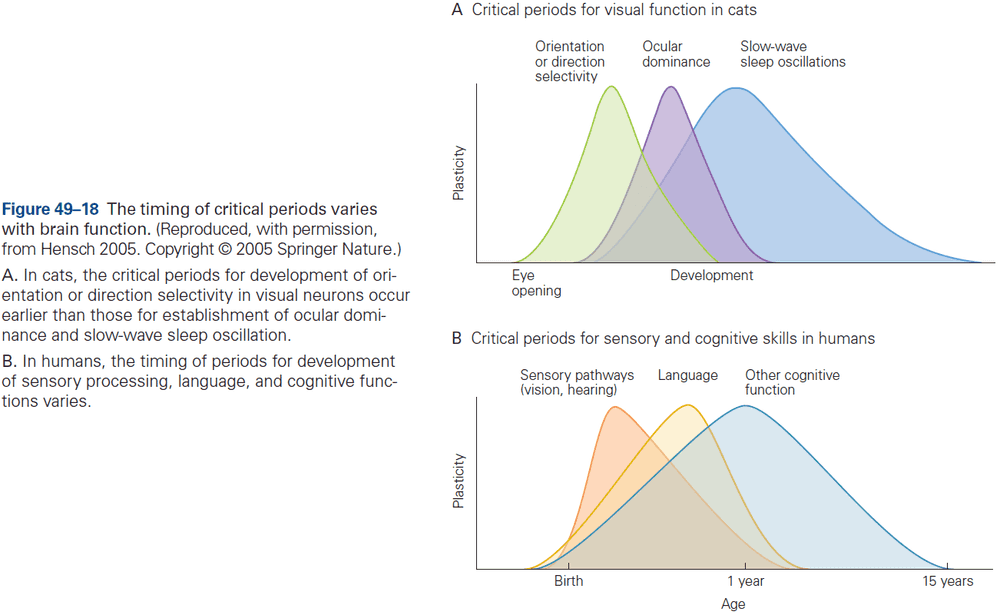

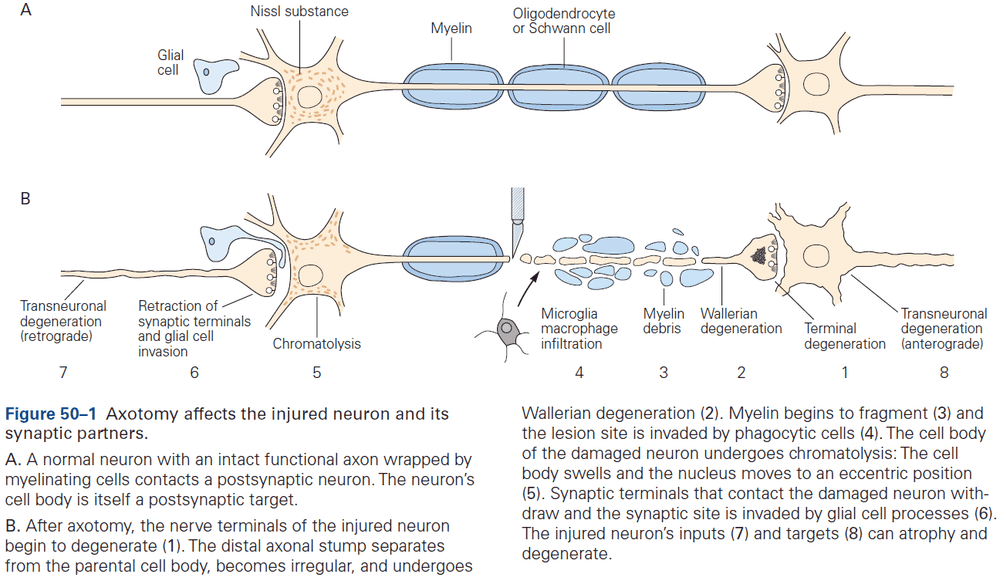

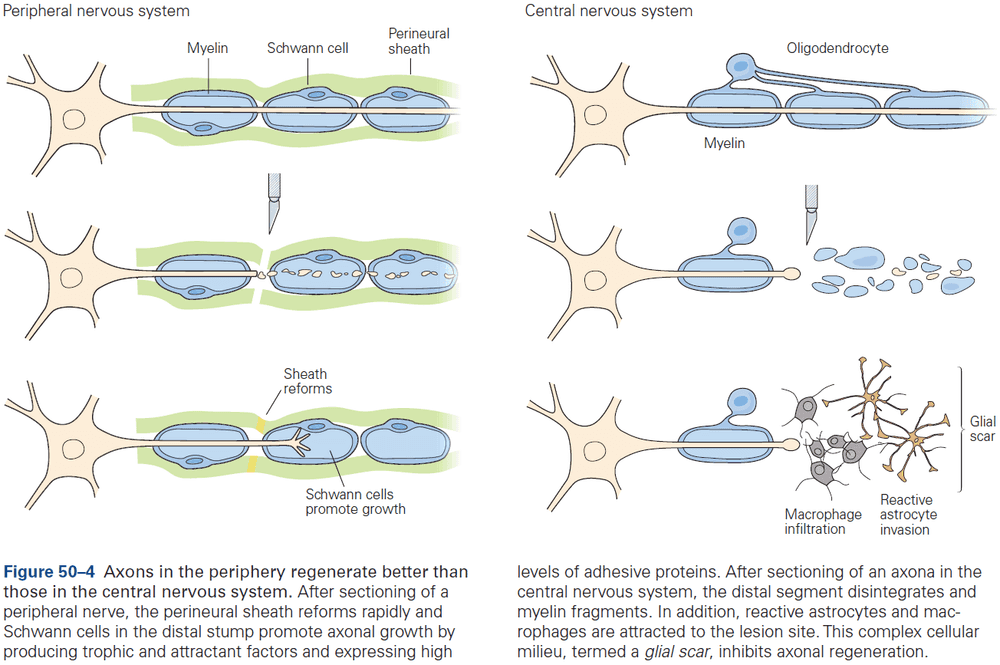

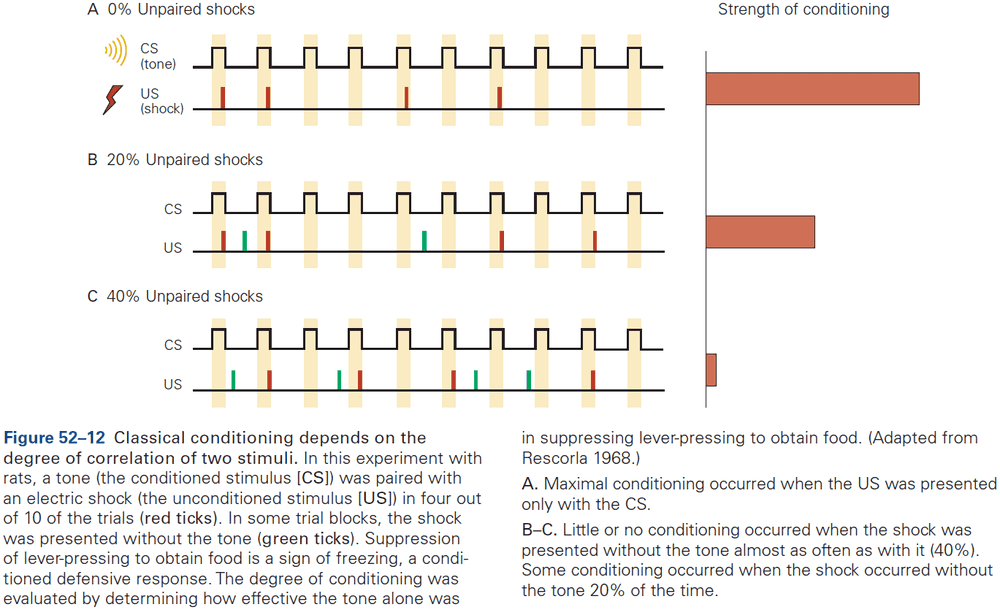

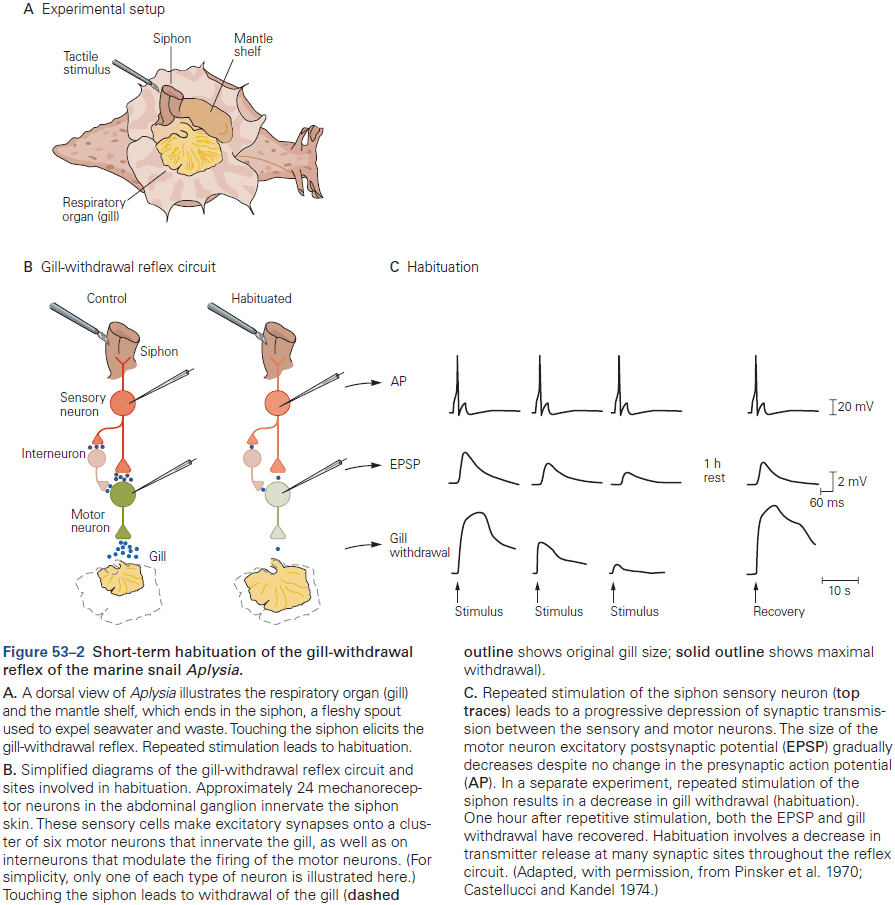

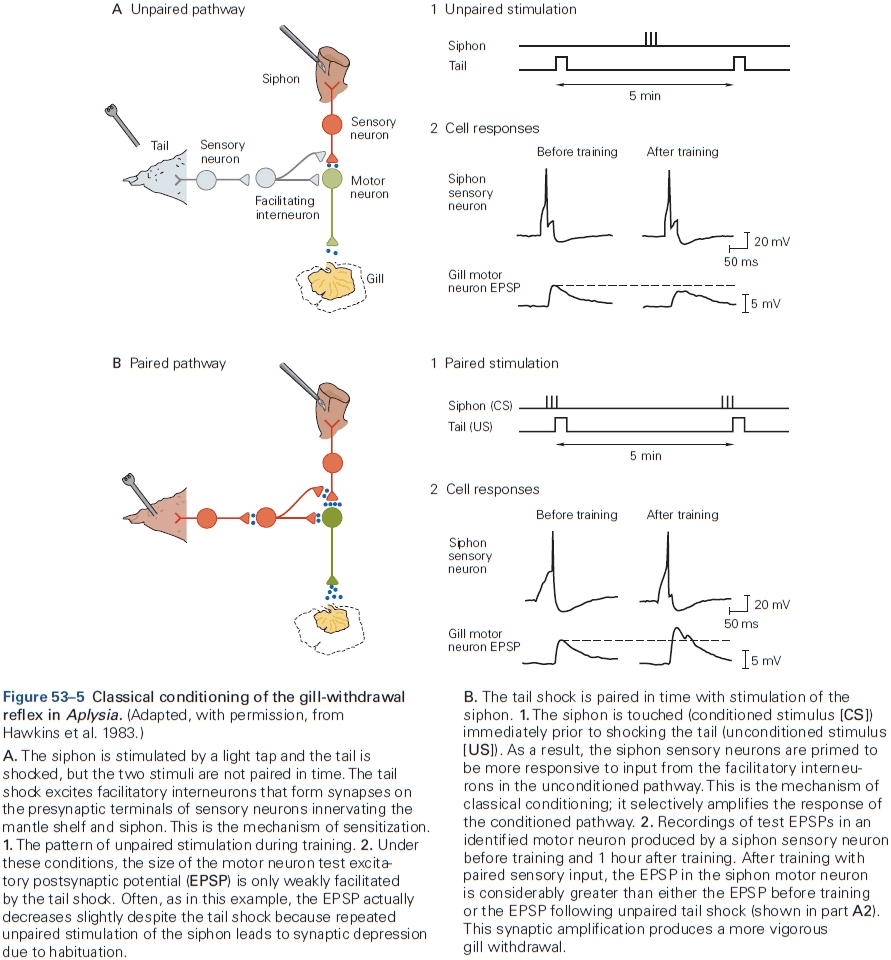

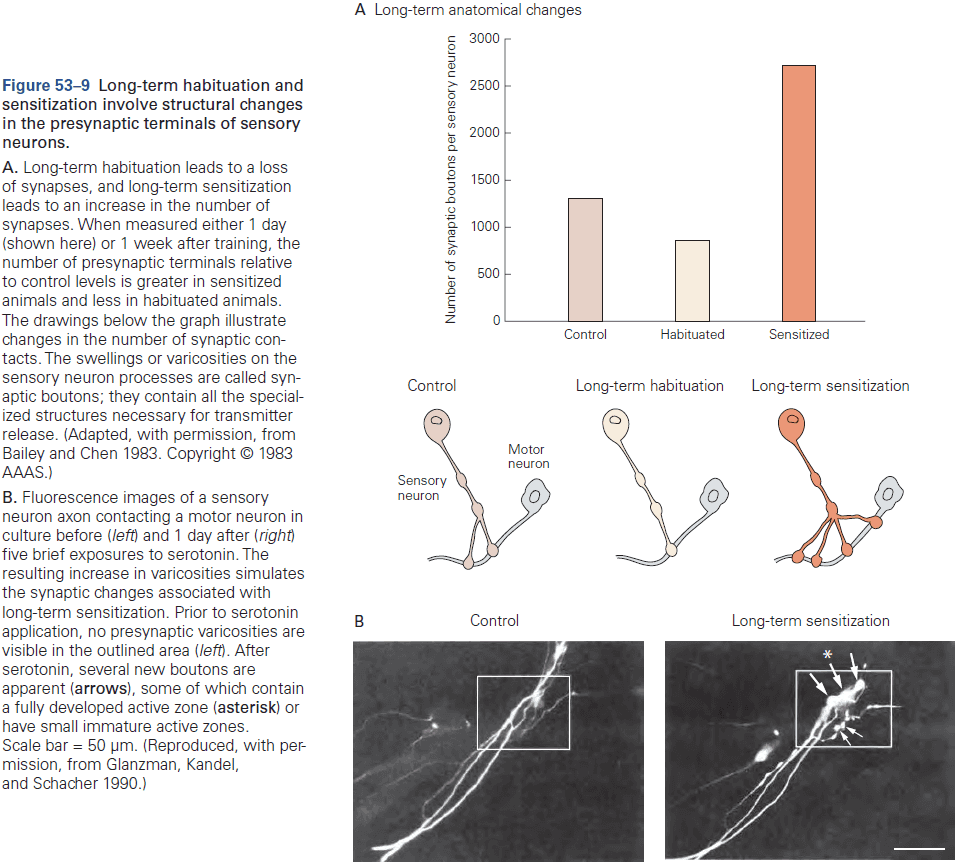

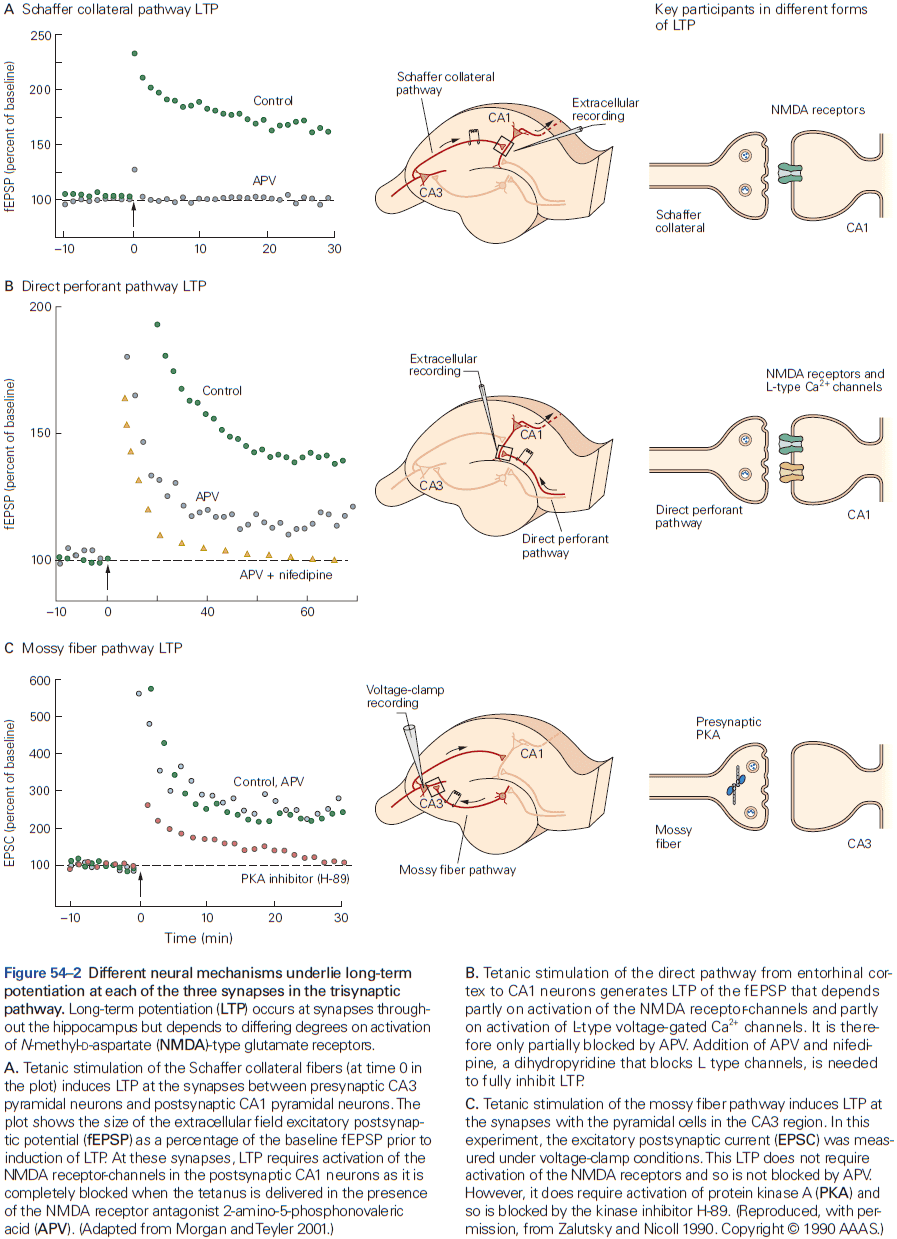

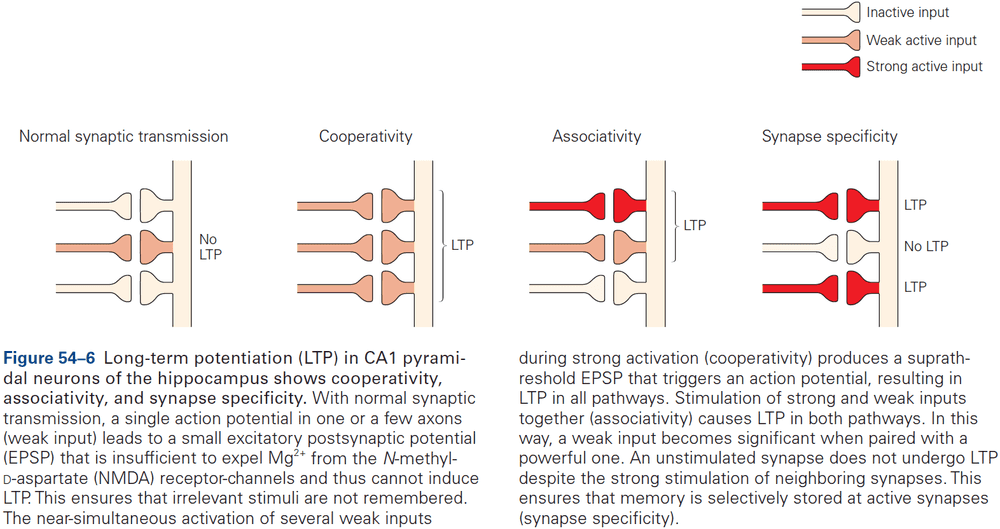

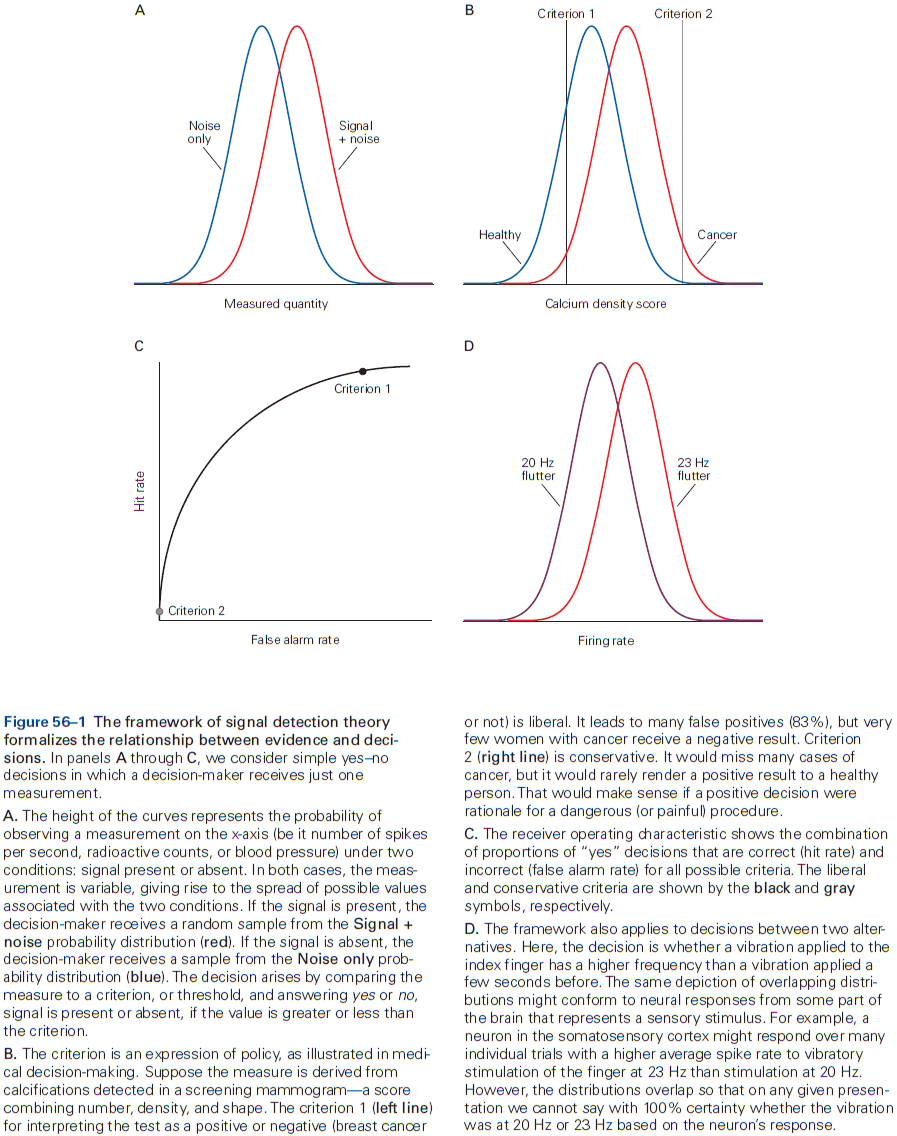

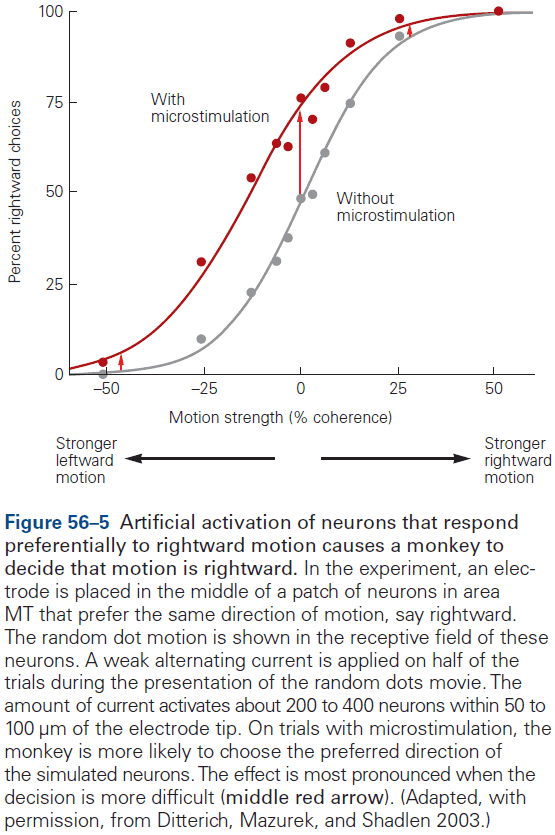

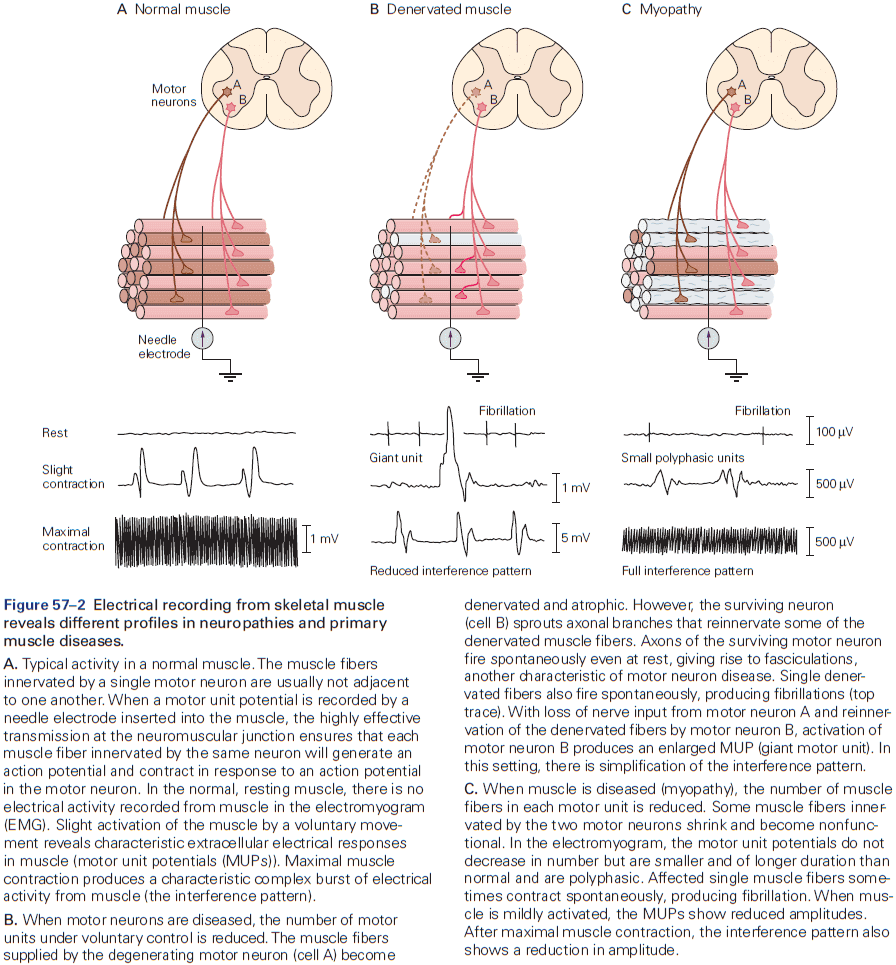

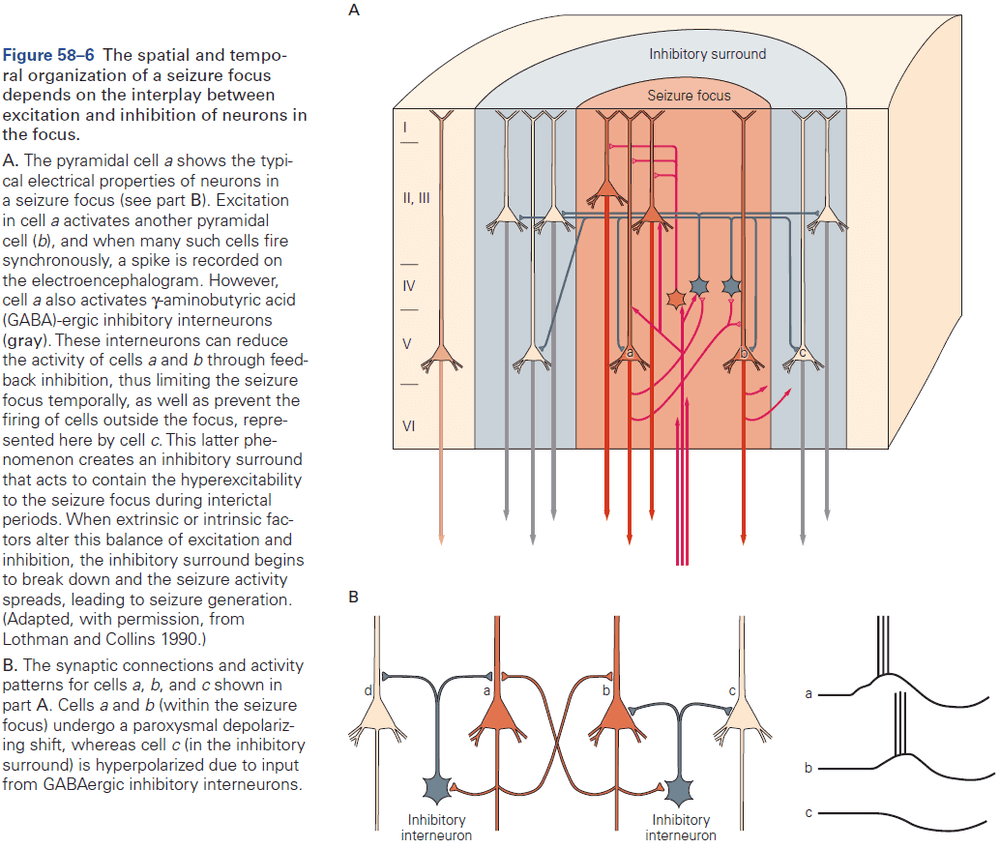

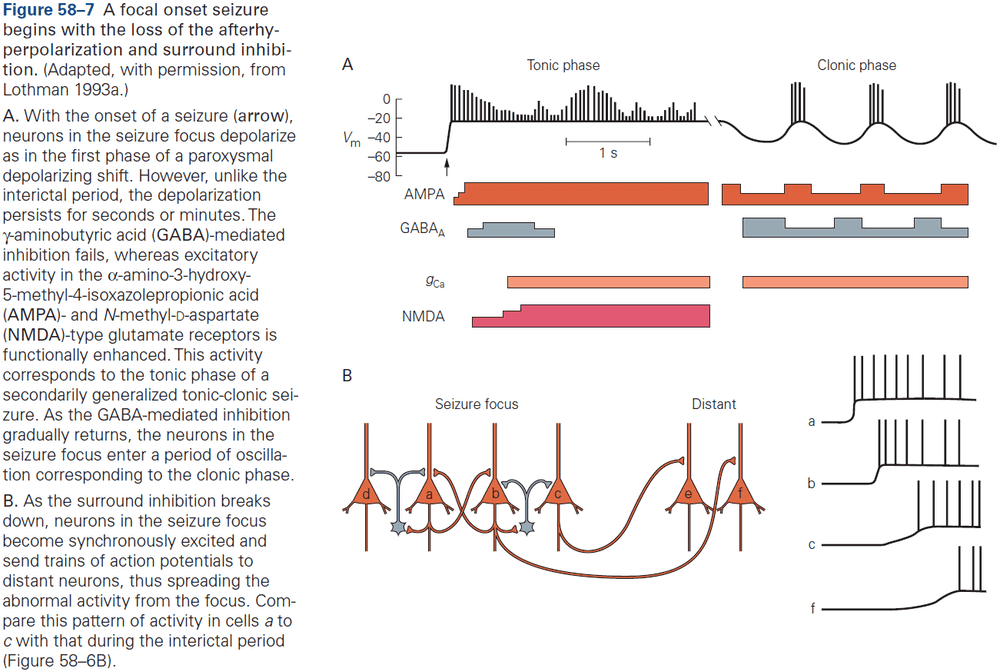

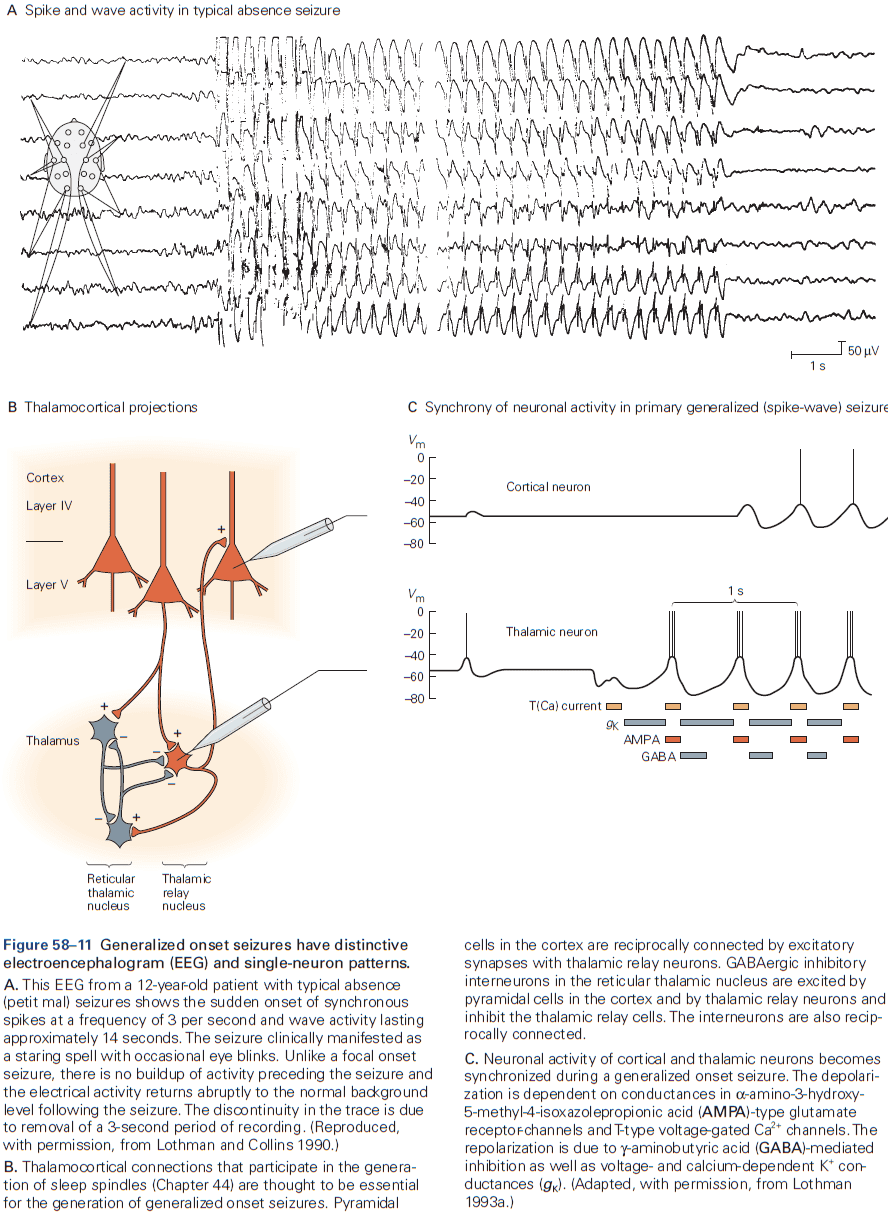

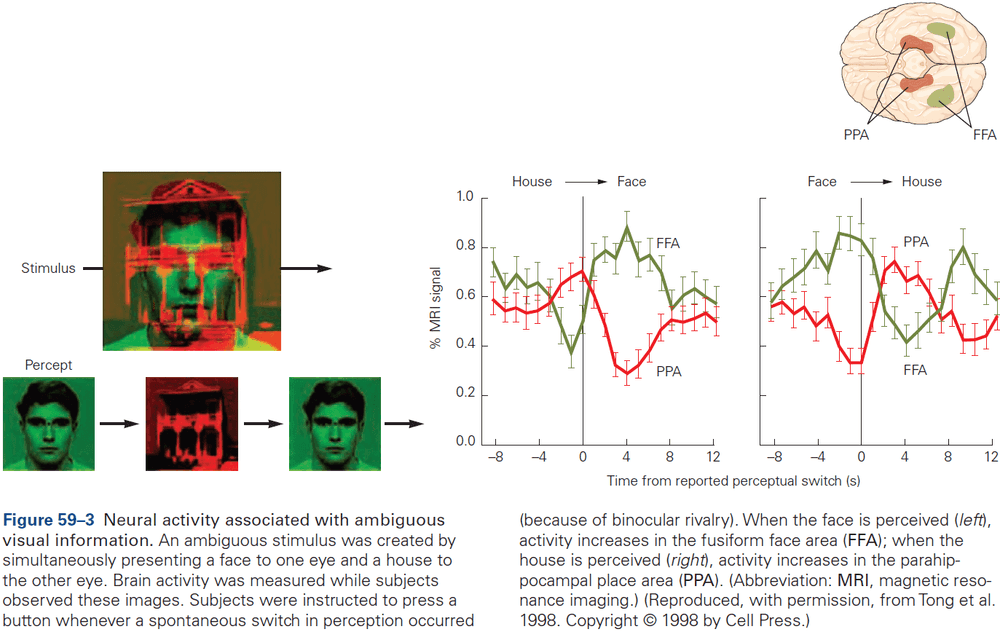

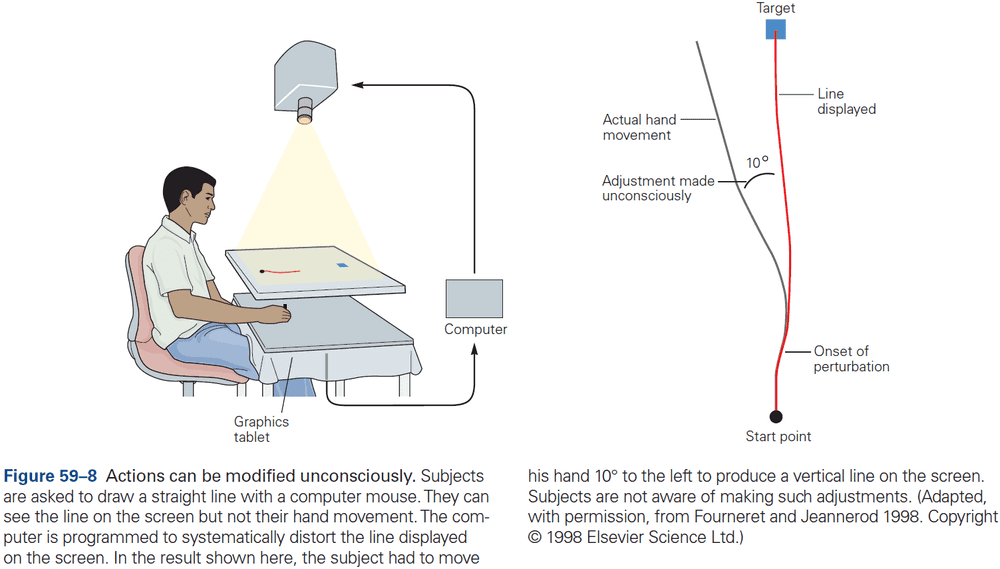

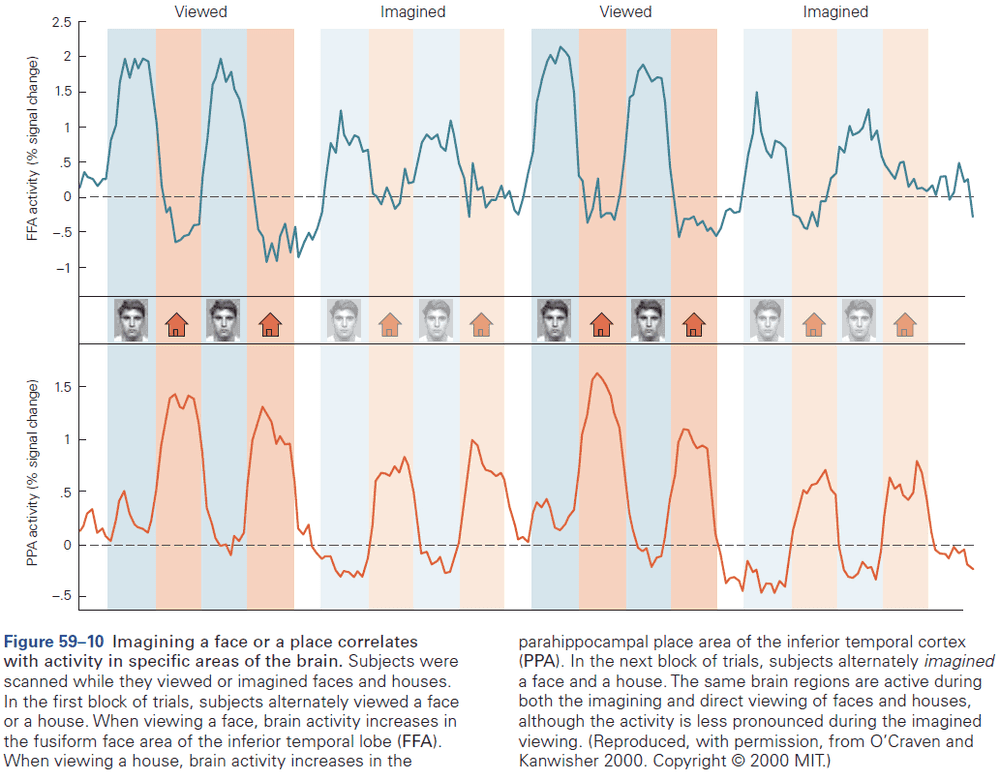

- The NMDA receptor is unique among ligand-gated channels because its opening depends on both membrane voltage and transmitter binding.