Cognitive Science: An Introduction to the Science of the Mind

By Jose L. BermudezMarch 23, 2019 ⋅ 64 min read ⋅ Textbooks

Artificial intelligence is basically willy nilly, stabbing in the dark, trying to model "natural intelligence".

Part I: Historical Landmarks

Chapter 1: The prehistory of cognitive science

1.1 The reaction against behaviorism in psychology

- Behaviorism: the belief that we should only study observable phenomena and measurable behavior. To link particular stimuli to particular responses.

- The behaviorism paradigm was challenged by various types of behavior that couldn’t be explained in terms of stimulus-response.

- Behaviorism assumptions of learning

- All learning depends on conditioning.

- All conditioning depends on the processes of association/reinforcement.

- Association/Reinforcement → Conditioning → Learning

- All learning is either associative learning (classical conditioning) or reinforcement learning.

- A rat is rewarded when it performs the relevant behavior, so the reward reinforces the behavior.

- This strengthens the association between the reward and the behavior which makes the behavior more likely. The rat becomes conditioned to perform the behavior.

- Latent learning: learning without any reinforcement/reward/feedback.

- It’s easier for animals to code spatial information in terms of places rather than in terms of particular sequences of movements.

- E.g. When a rat’s food is moved vs when the rat is moved, it’s faster for the rat that moved to find its food than when the food was moved. Suggesting maps are built to be invariant, not individual focused.

- Representations: stored information about the environment/object/person/thing.

- How are representations formed? used? transformed?

- Behaviorism explains complex behaviors as a series of linked sequences of responses (like a chain).

- However, another view is that complex behaviors arise from planning and are organized in a hierarchy (can break a behavior down into simpler behaviors).

- Hypothesis of Subconscious Information Processing: much of what we do is under the control of planning and information processing mechanisms that operate below the threshold of awareness. We do a lot of things without being aware.

- Hypothesis of Task Analysis: we can break down a complex task into a hierarchy of more simpler tasks. Reductionism vs emergence.

1.2 The theory of computation and the idea of an algorithm

- Algorithm: a set of steps to solve a problem.

- Universal Turing Machine: a Turing machine that can simulate any specialized Turing machine by taking that machine (plus its input) as its input.

- Church-Turing Thesis: anything that can be done in mathematics by an algorithm can be done by a Turing machine. Turing machines can compute anything that can be algorithmically computed.

1.3 Linguistics and the formal analysis of language

- Two types of sentence structures

- Deep structure: how a sentence is made up of basic parts and basic rules.

- Surface structure: the actual organization of the words.

- Languages are hierarchically organized as sentences can be broken down into components.

- E.g. Subject, noun phrase, and verb phrase.

1.4 Information-processing models in psychology

- How can we measure information?

- Information channel: a medium that transmits information from sender to receiver.

- E.g. Wires, optic fiber, or air.

- Humans are limited in the absolute judgments that they can make compared to relative judgments.

- E.g. It’s more difficult to identify a tone than to compare two tones and identify the higher pitched tone.

- Information-processing bottleneck: an upper bound on the number of distinct items that can be processed simultaneously regardless of the source.

- E.g. Audio, visual, or touch.

- The bottleneck for human short term memory is around seven items or three bits (Since 2^3 = 8 which is close to 7).

- Channel capacity: the amount of information that an information channel can reliably transmit.

- It’s theorized that our sensory systems are all information channels with roughly the same channel capacity.

- Why do we have these limits? The answer may be due to energy limitations.

- One way of bypassing a channel’s capacity is to chunk information.

- Chunking: when we group multiple items together.

- E.g. Remembering a phone number in chunks of three such as 123-456-789.

- Natural language is the ultimate chunking tool as it chunks letters into words, words into sentences, and sentences into ideas.

- Cocktail party phenomenon: how we’re able to focus on one person in a party when everyone else is also talking. This is also known as selective attention.

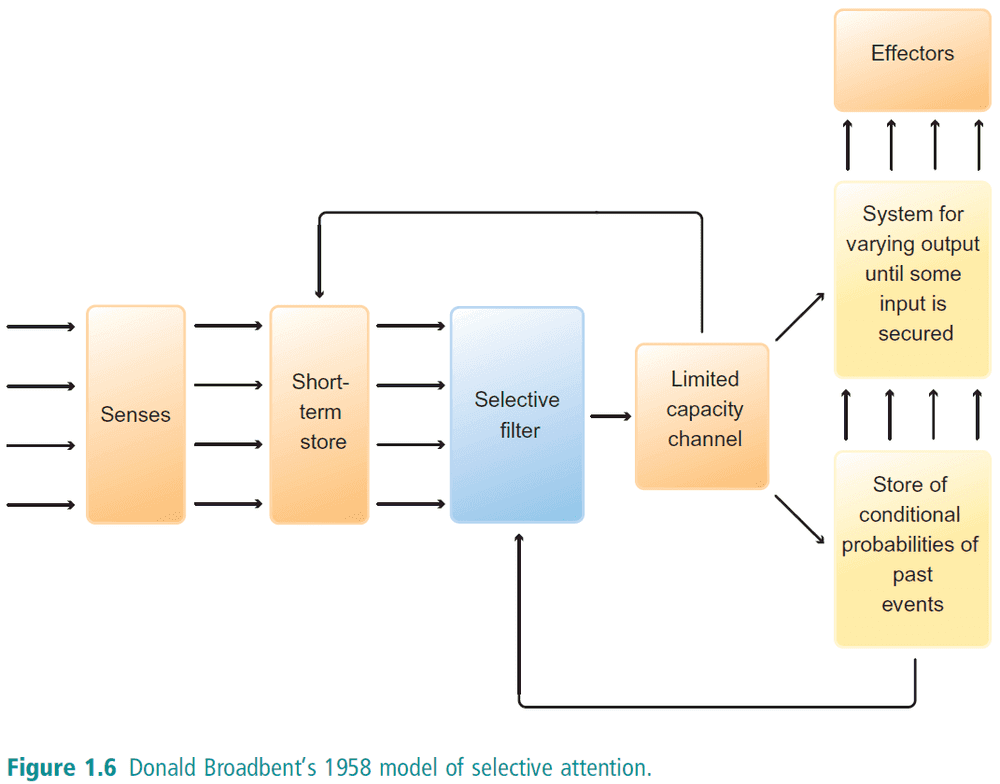

- The sensory input is first filtered before reaching the limited capacity channel. The filter is “programmed” by another system.

1.5 Connections and points of contact

- Information is gained through learning and is stored as a representation, thus organisms are information processors.

- Information processing is done by dedicated and specialized systems. These systems perform simpler tasks to process the information.

- We can understand how a cognitive system works as a whole by understanding how information flows through the system.

- Cognition as a form of information processing. Processing as in how information is represented, transformed, and exploited.

Summary

- The fundamental idea of cognitive science is that the mind is an information processor. That mental operations involve processing information.

- Should we abstract away the brain to understand the mind?

- Even very basic types of behavior (such as the behavior of rats in mazes) seems to involve storing and processing information about the environment.

- Information relevant to cognition can take many forms. From information about the environment to information about how sentences can be constructed and transformed.

- Perceptual systems can be viewed as information channels and we can study both the general properties of those channels and way in which information flows through those channels.

- Mathematical logic and theory of computation shows us how information processing can be mechanical and algorithmic.

- Much of the information processing that goes on in the mind takes place below the threshold of awareness.

Chapter 2: The discipline matures: Three milestones

2.1 Language and micro-worlds

- Language is more than a tool used for communication. It’s also a tool used for thinking.

- SHRDLU is a program that can manipulate objects in a virtual environment. It can also answer questions related to the objects.

- E.g. What object is in front of the red cube?

- Three reasons why SHRDLU is important

- It shows how abstract rules and principles could be implemented.

- It shows the general approach of breaking down systems into distinct components.

- It shows how understanding language is an algorithmic process.

- Approach the understanding of systems by starting from the abstract/general and moving down towards the concrete/specific implementation.

2.2 How do mental images represent?

- One way to test our understanding of a cognitive ability is to try to build it.

- Artificial intelligence can be thought of as a way to experiment with models in cognitive science.

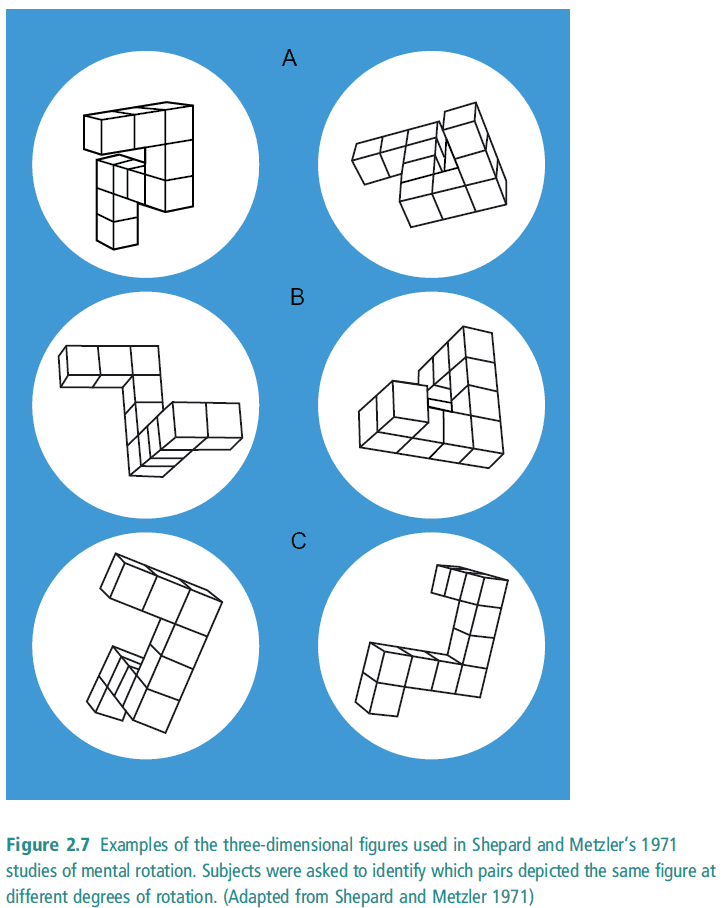

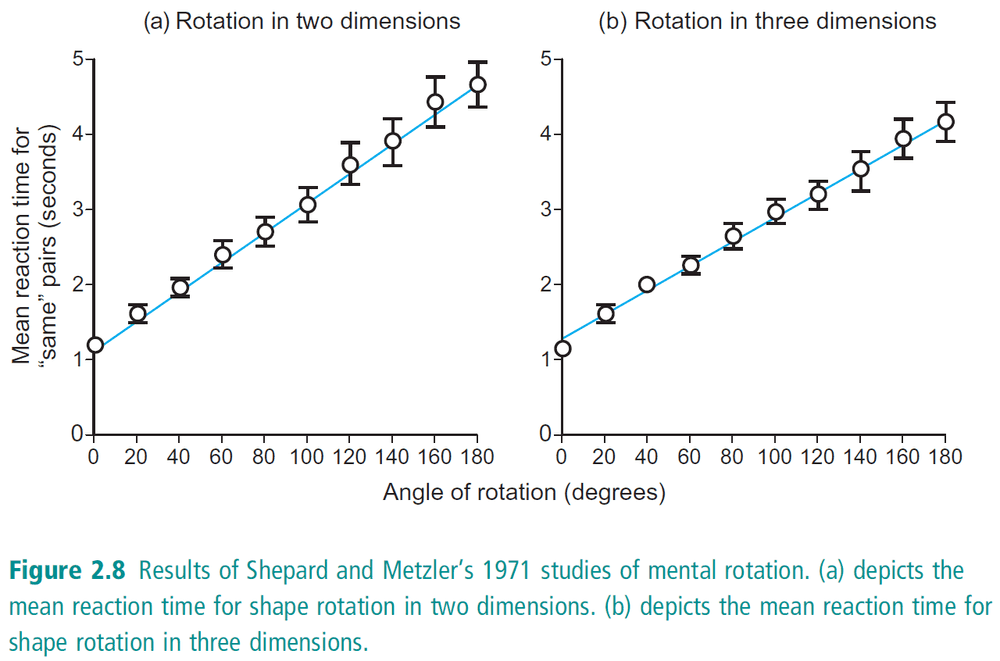

- Mental rotation of three-dimensional objects experiment: given pairs of 3D figures, determine as quickly as possible, which pairs are the same but rotated.

- There is a direct, linear relationship between the length of time that subjects take to solve the problem and the degree of rotation between the two figures.

- The larger the angle of rotation, the more time it takes to determine if the figures are the same.

- Questions from the experiment

- What is the “mind’s eye”? And how did we obtain this skill?

- What cognitive machinery makes this possible?

- Why is the relationship linear?

- A linear relationship suggests that the rotation in our head is linear (aka at a constant rate).

- Why isn’t it say exponential or constant? Default assumption of the brain starts with zero rotation and linearly rotates it?

- What about the case of going past 180 degrees? Does clockwise or counterclockwise matter?

- Why is it linear in both the 2D and 3D cases?

- How is the information represented and how is it transformed?

- One feature of digitally encoded information is that the time it takes to process information is typically a function only of the quantity of information (number of bits).

- The quality of information doesn’t matter to computers, only the quantity.

- E.g. Big-O which characterizes the growth of algorithms only cares about input size, not input type.

- However, the mental rotation experiment shows that it takes varying amounts of time to solve a problem even though the quantity of information remains the same.

- Personal hypothesis: People do a brute force “search” to see if the figures match. We do this by first having a base state, aka the left image, and then mentally rotating it by a few degrees and seeing if it matches. If it doesn’t, then rotate some more. Eventually, we either find a match or we exhaust all possible rotation degrees and we say that they don’t match.

- Digital representation: the connection between what we might think of as the unit of representation and what that unit represents is completely arbitrary. Think how we bind meaning to words.

- E.g. For computers, an image or sound file are both represented by zeros and ones even though bits have nothing to do with colors or sounds.

- Imagistic representation: opposite to a digital representation where the representation matches the meaning assigned to it.

- E.g. A map. What it represents is similar to reality as the representation is secured though resemblance.

2.3 An interdisciplinary model of vision

- Reverse engineering: the process by which we take an object and try to work backwards from its structure and function to its basic design principles.

- Reverse engineering = science.

- Marr’s three levels for analyzing systems (top-down analysis)

- Computational level: what are the goals, what are the problems, what are the solutions, and what are the limitations on those solutions?

- Algorithmic level: how the system solves the problem and achieve its goals?

- Implementation level: how to find a physical realization for the algorithm?

- Marr’s conclusions from Warrington’s work

- Information about the shape of an object must be processed separately from information about what the object is for and what it is called.

- The visual system can deliver a specification of the shape of an object even when the object isn’t recognized.

- The representation of a object should be object-centered rather than egocentric.

- E.g. If the viewer’s perspective changes or the object moves, we can still keep track of the object even though its representation changes. This means we have a viewer-independent representation of the object.

Summary

- SHRDLU illustrated how abstract grammatical rules might be represented in a cognitive system.

- The imagery debate is about whether the different effects revealed by experiments on mental imagery can or cannot be explained in terms of digital information processing models.

- Marr identified three different levels for analyzing systems

- Computational

- Algorithmic

- Implementational

Chapter 3: The turn to the brain

3.1 Cognitive systems as functional systems

- It’s widely viewed that cognitive systems are functions systems. And functional systems have to be analyzed in terms of their function - what they do and how they do it.

- It’s also viewed that cognitive processes can be studied independently of their physical realization.

- Multiply realizable: a function can be implemented/realized in many different physical structures.

- E.g. The function of eyes is to see but different animals have implemented different eyes.

- Maybe cognition can be realized in machines - that’s the goal of AI.

- Certain types of mental activity are multiply realizable due to evidence of neural plasticity.

3.2 The anatomy of the brain and the primary visual pathway

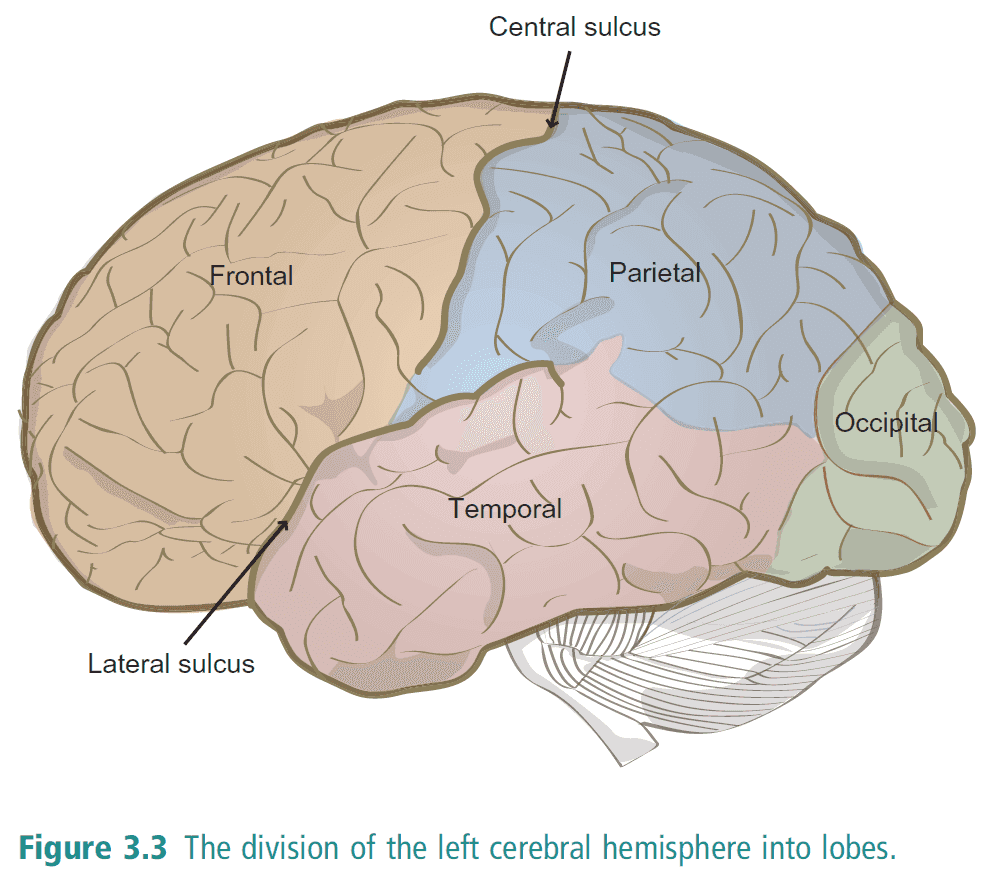

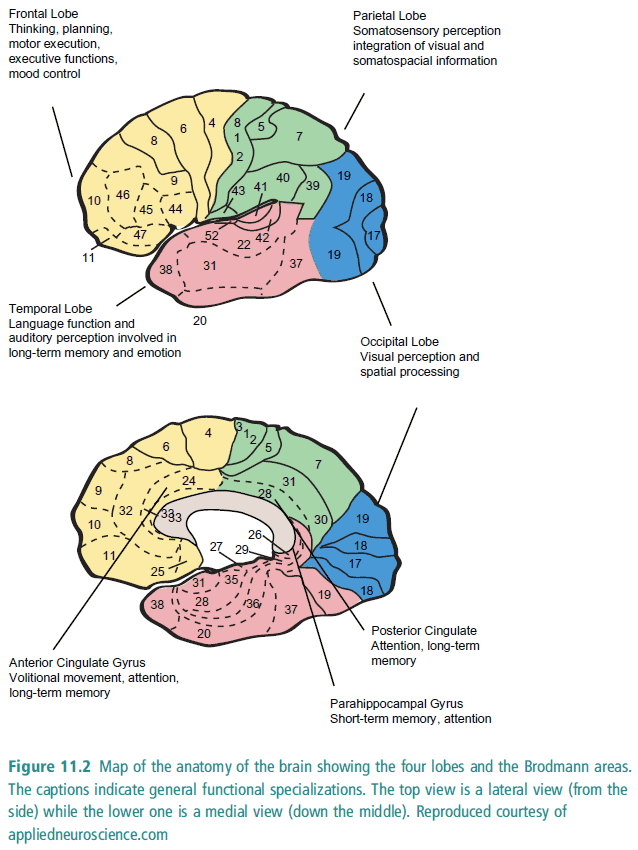

- Frontal lobe: reasoning, planning, parts of speech, movement, emotions, and problem solving.

- Parietal lobe: movement, orientation, recognition, perception of stimuli.

- Occipital lobe: associated with visual processing.

- Temporal lobe: associated with perception and recognition of auditory stimuli, memory, and speech.

- Vision from the right side of both eyes is processed by the left brain and vice versa.

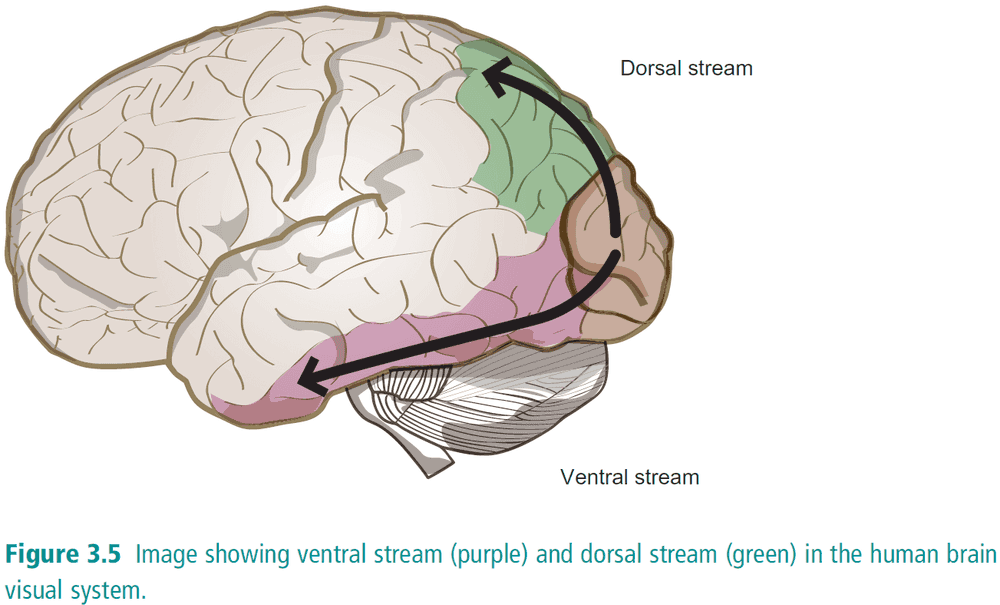

- Theory that visual data follows along two paths depending upon the type of information it is. Think parallel processing.

- Ventral stream: information relevant to recognizing and identifying objects follows a bottom route towards the temporal lobe. The “what” system.

- Dorsal stream: information relevant to locating objects in space follows a top route towards the parietal lobe. The “where” system.

- The brain localizes specific functions to specific areas of the brain.

- The brain is able to compensate for the loss of function in one hemisphere by using it in the other hemisphere via the corpus callosum.

- This contrasts with Marr’s approach as this is bottom up.

3.3 Extending computational modeling to the brain

- There are several reasons why we shouldn’t ignore the brain/hardware and abstract away the details

- The temporal dimension of cognition. The right answer is no use if it comes at the wrong time.

- The mind is realized by the brain.

- Cognitive abilities degrade gracefully - they aren’t all-or-nothing. This is due to how the brain is wired and the biochemistry of neurons.

- Hardware limitations translates to software limitations.

- Artificial neural networks bridge algorithm and implementation.

- ANN key features

- Parallel processing.

- Layers of neurons.

- What distinguishes one ANN from other is the pattern of weights between units.

- There are no intrinsic differences between one unit/neuron and another. The differences lie in the connections/weights.

- The hidden units are the key to the computational power of ANNs.

- ANNs learn by adjusting their weights.

- ANNs have no memory, or rather the only traces of what happened exists in the weights of the network.

3.4 Mapping the stages of lexical processing

- Understand complex systems by simplifying them.

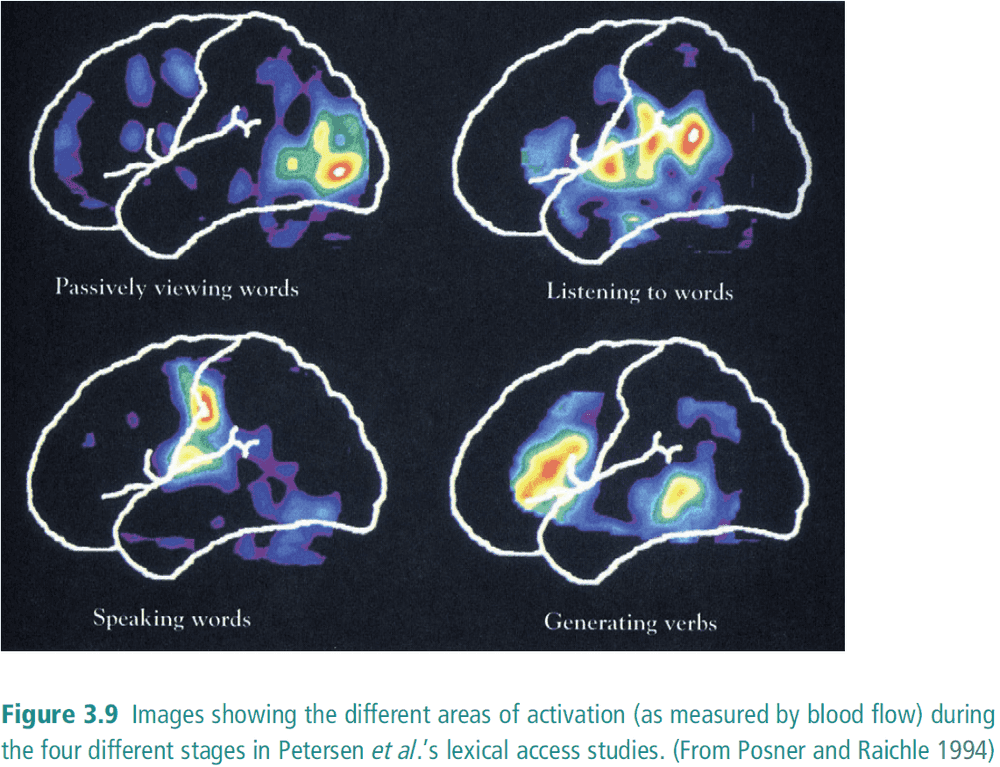

- PET measures the blood flow in the brain.

- Two models for single-word processing

- neurological

- cognitive

- Neurological model

- Serial

- Word processing follows a single, invariant path.

- To access what the word means, the brain needs to know what the word sounds like.

- We can’t read a word and then pronounce it without invoking what the word means.

- Cognitive model

- Parallel

- Speaking, reading, and understanding a word is separate and independent.

- Experiments using PET suggest the neurological model is inaccurate due to each function requiring a different area of activation.

Summary

- We’ve identified two information processing pathways for visual information, the “what” pathway and the “where” pathway.

- Artificial neural networks are a model of the brain and learns by adjusting its weights.

- The processing of one word is supported by a parallel model of processing where reading, hearing, speaking, and understanding are independent.

Part II: The Integration Challenge

Chapter 4: Cognitive science and the integration challenge

4.1 Cognitive science: An interdisciplinary endeavor

- We should take both a top-down approach and a bottom-up approach.

- Our theories of what the mind does has to co-evolve with our theories of how the brain works.

- Two important themes of cognitive science

- Interdisciplinary. This reflects the different levels of organization at which the mind and brain can be studied.

- Information processing. This reflects our understanding of how we can model the mind as a digital computer.

- This hexagon isn’t a good model cognitive science because it doesn’t give any sense of a unified intellectual enterprise. The whole isn’t greater than the sum of its parts.

- It also doesn’t take into account other relevant fields such as math (dynamical systems theory), ecology (cognition in other animals), political science (game theory)

4.2 Levels of explanation: The contrast between psychology and neuroscience

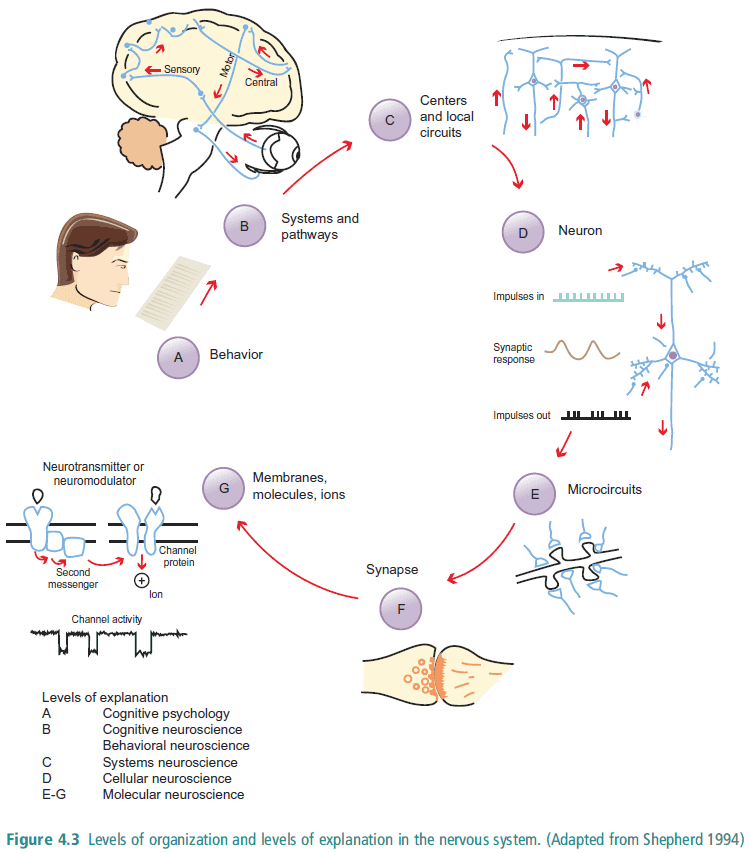

- One way of separating psychology and neuroscience is through the idea of levels.

- Even though psychology has various sub-fields, there is a continuity of methodology which links those sub-fields into psychology.

- Psychology also uses data from the same level, the level of the whole organism.

- However, neuroscience is different in that it uses data from different levels. Those levels reflect the different levels of organization in the brain and central nervous system.

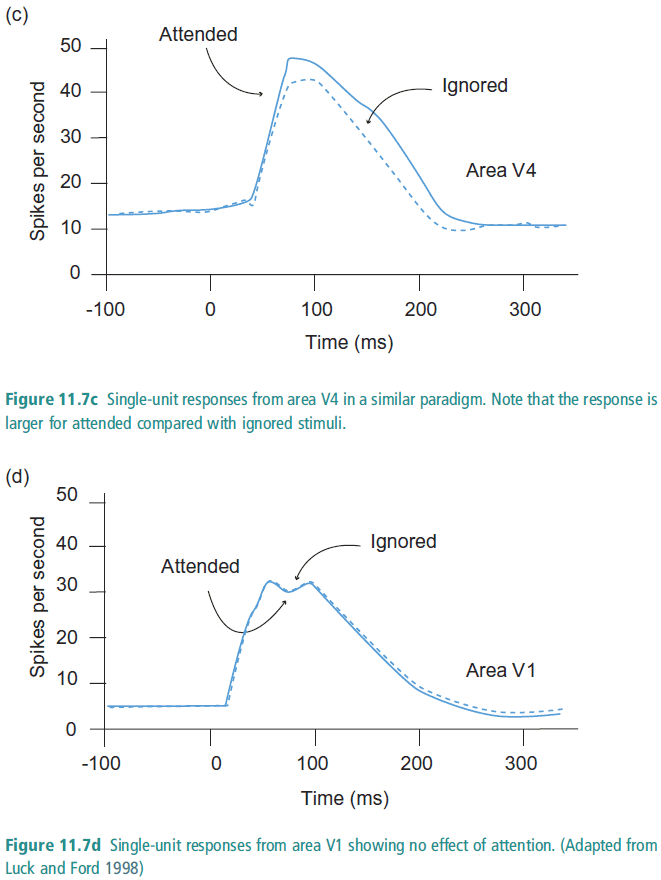

- Neuroscience believes that the basic information processing units in the brain are populations of neurons rather than individual neurons.

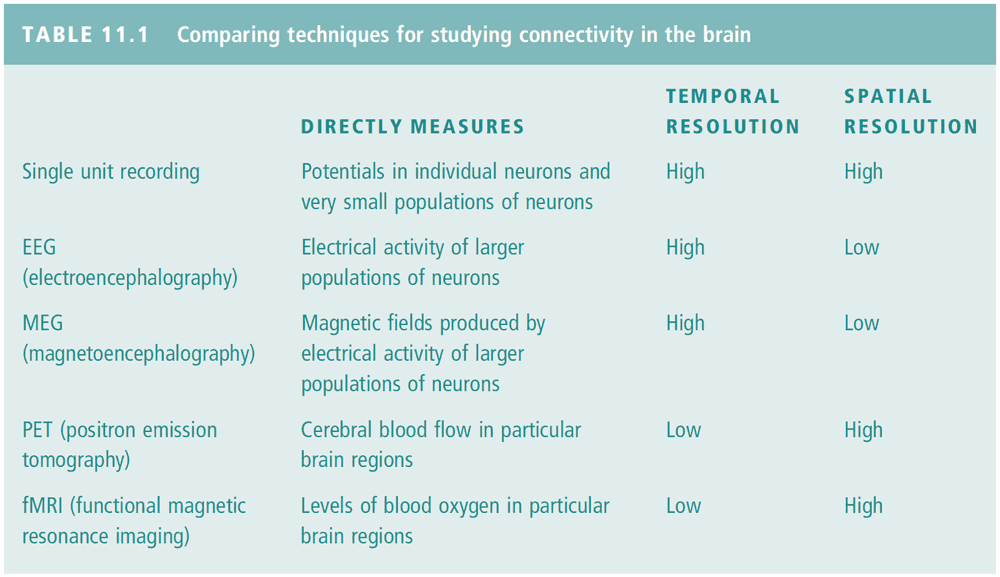

- Different branches of neuroscience uses different tools that vary in spatial resolution and temporal resolution.

4.3 The integration challenge

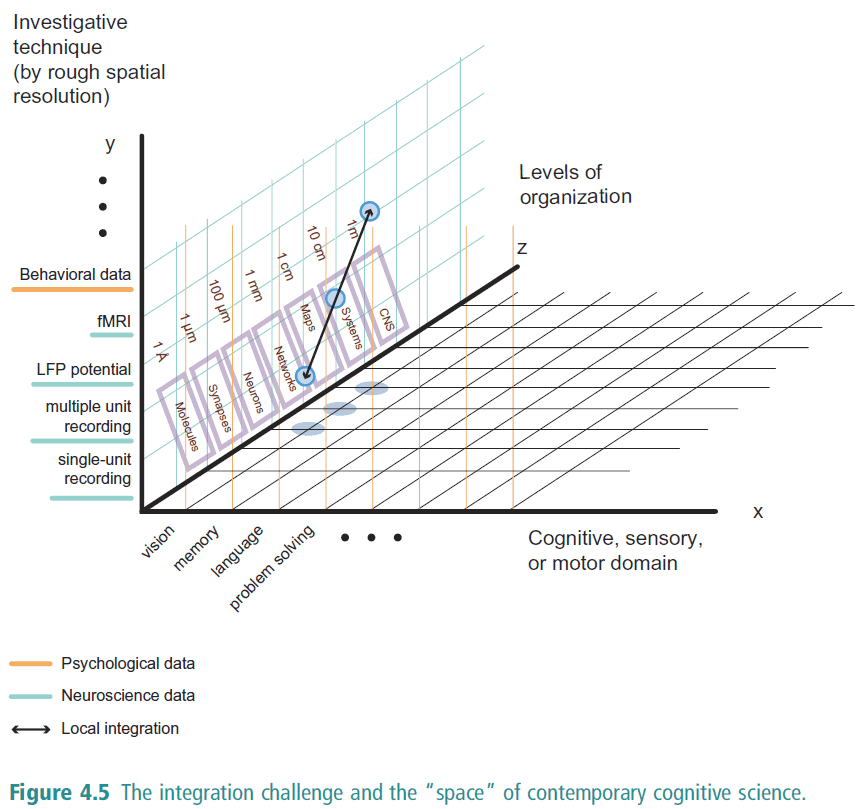

- Integration challenge: explaining how all of the different levels of explanation fit together.

- The integration challenge arises because cognitive science has three dimensions of variation

- Varies according to the aspect of cognition being studied.

- Varies according to the level of organization at which that aspect is being studied.

- Varies according to the degree of resolution of the techniques and tools that are being used.

- We can map these three variables onto a three dimensional space.

- One way of thinking about the ultimate goal for cognitive science is that it sets out to provided a unified account of cognition; a unified Theory of Cognition. Similar to the unified Theory of Everything in Physics.

- However, some are skeptical of whether these unified theories are possible.

- There are two strategies for approaching the integration challenge

- Global strategies: overarching models that explain how cognitive science as a whole fits together.

- Local strategies: integration across levels of organization and levels of explanation.

4.4 Local integration I: Evolutionary psychology and the psychology of reasoning

- We want to understand how people solve problems and reason.

- One solution is that human reasoning uses basic principles of logic and probability theory but this doesn’t seem true.

- An important feature of logic and probability is that their principles are universal (i.e. they are domain-general).

- People are not good in determining if conditional statements are true or not as demonstrated by the card selection task (If a card has a vowel on one side, then it has an even number on the other).

- However, if the selection task is framed as a real world problem, then the performance increases.

- E.g. If a person is drinking beer, then that person must be over 19 years of age.

- This suggests that we are good at reasoning in domain-specific areas such as deontic conditionals (conditionals that express rules, prohibitions, entitlements, and agreements).

- One theory on why we have domain-specific reasoning is that the mind has a dedicated module for the detection of cheaters. Aka a fairness or morals module.

- How did cooperative behavior emerge?

- The TIT FOR TAT heuristic strategy follows two rules

- Always cooperate in the first encounter.

- In any following encounter, do what your opponent did in the previous round.

- This strategy is powerful for the following reasons

- It’s simple.

- It follows the rule “you should do unto others as they do unto you”.

- The idea of a module to detect cheating is an example of local integration between cognitive psychology and evolutionary psychology.

- We evolved this module in response to our environment and its effects are seen in the Watson card selection experiment.

4.5 Local integration II: Neural activity and the BOLD signal

- PET measure local blood flow, fMRI measures levels of blood oxygenation.

- fMRI is built on the principle that deoxygenated hemoglobin disrupts magnetic fields thus we can measure the blood that lacks oxygen.

- BOLD: blood oxygen level dependent. The difference between blood oxygen levels.

- fMRI measures the BOLD contrast which indirectly measures neuronal activity, but what exactly is the neuronal activity that generates the BOLD contrast?

- We are trying to integrate information about blood flow with information about the behavior of populations of neurons. And then we are trying to understand how individual neurons contribute to the behavior of neural populations.

- It’s hypothesized that the neural activity correlated with the BOLD contrast is a function of the firing rates of populations of neurons.

- Specifically, the function is a linear relationship where each increase in the BOLD contrast is an index of higher neural firing activity.

- However, neurons do more than just fire as firing only occurs when the internal voltage passes a threshold. Neurons are selective.

- This means that there can be plenty of activity in a neuron even when the neuron doesn’t fire.

- What role do signals that don’t surpass the threshold potential play in cognition?

- Does BOLD measure the input or output of neurons?

- The BOLD contrast is more highly correlated with the LFP (local field potential aka the inputs) than the firing activity of neurons (the outputs).

Summary

- Cognitive science is interdisciplinary.

- Disciplines and sub-fields across cognitive science differ in three dimensions

- The type of cognitive activity

- The level they study it at

- The degree of resolution of the tools that they use

- The integration challenge is the challenge of providing a unified theoretical framework for studying cognition.

- Abilities in conditional reasoning are highly context-sensitive.

- It’s hypothesized that we have evolved a specific module dedicated to the detection of cheaters/free riders which explains why reasoning is context-sensitive.

- fMRI gives us a measure of cognitive activity but we don’t know how this is related to neural activity.

- Experiments seem to show that fMRI is correlated to the neural input rather than neural output.

Chapter 5: Tackling the integration challenge

5.1 Intertheoretic reduction and the integration challenge

- Intertheoretic reduction: solves the integration challenge by reducing the various theories of cognitive science to a fundamental theory (similar to how we could unify the physical sciences by reducing them all to physics). It relates between laws at different levels of explanation. It’s a translation in a sense.

- The integration challenge isn’t unique to cognitive science, other sciences also face a similar problem.

- Fundamental science: scientific disciplines that deal with the most basic levels of organization in the natural world.

- How do the non-fundamental scientific disciplines relate to the most fundamental one?

- The relationship between non-fundamental and fundamental could be reductionism, emergence, something else?

- Conditions of reduction

- The two theories must have a shared vocabulary that can be used to translate between the theories.

- One theory must explain how the other theory can be derived from itself.

- E.g. Thermodynamics can be reduced to the theory of statistical mechanics. An example of a bridge between the two is that temperature is the mean molecular kinetic energy.

- Problems with applying intertheoretic reduction to cognitive science

- Few laws in cognitive science

- Lack of a formal description that could be used to translate

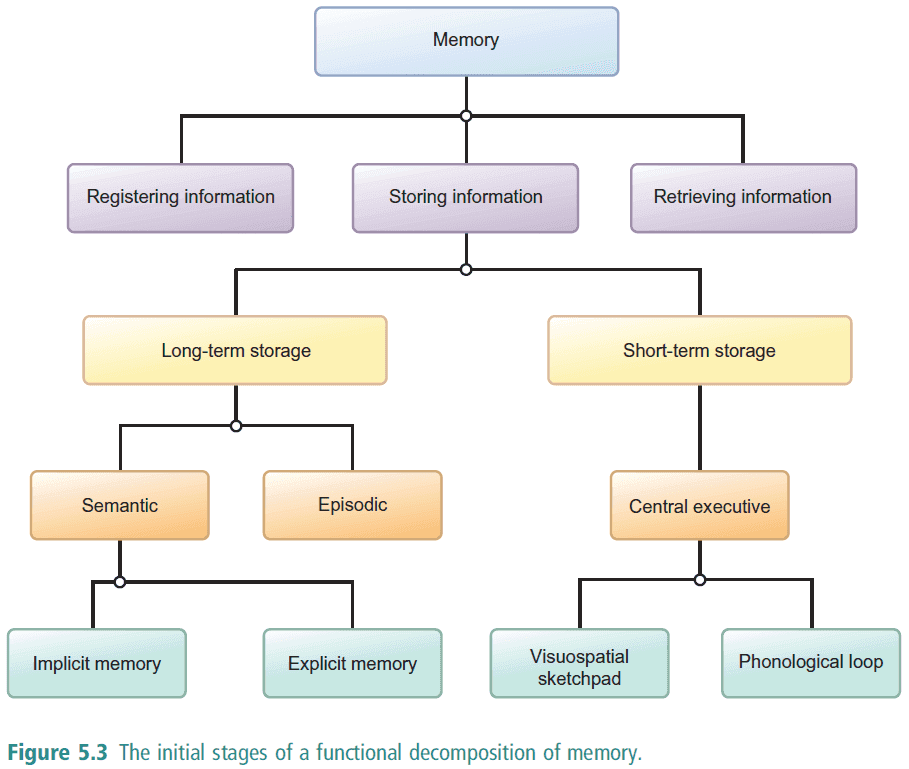

- Functional decomposition: the process of explaining a cognitive capacity by breaking it down into sub-capacities that can be separately and tractably treated. We can keep breaking down until we reach a level of “axioms”.

- E.g. Memory can be broken down (by function) into three functions of registering, storing, and retrieving. Storing can then be broken down into short-term memory and long-term memory.

- Anterograde amnesia: affecting memory of events after the onset of brain injury.

- Retrograde amnesia: affecting memory of events before the onset of brain injury.

5.2 Marr’s tri-level hypothesis and the integration challenge

- The mind is an information processing system. The brain is a signal-processing system.

- Marr’s three levels (tri-level hypothesis) are computational, algorithmic, and implementational.

- The computational level specifies what information is transformed into.

- The algorithmic level specifies the steps for how the information is transformed, but we first have to know and specify what it is that we’re working on. In other words, how the information is encoded and represented.

- The implementational level specifies how the algorithm is run or carried out.

- The three levels are distinct but not independent as it depends on the lower level to implement and explain the higher level. There’s a dependency.

- Problems with applying the tri-level hypothesis to cognitive science

- Applicable to only a limited and precisely identifiable type of cognitive system. Cannot generalize.

- Doesn’t work well for non-modular cognitive systems

- Modular cognitive systems have the following characteristics

- Domain-specificity

- Informational encapsulation

- Mandatory application

- Fast

- Fixed neural architecture

- Specific breakdown patterns

- There seems to be a close relation between cognitive systems being modular and it being susceptible to Marr’s top-down analysis.

- Frame problem: how to build a system that will correctly identify what information and which inferences should be pursued in a given situation.

5.3 Models of mental architecture

- Mental architecture: solves the integration challenge by looking for a general model of the organization of the mind and the mechanics of cognition that incorporates some of the basic assumptions common to all disciples and fields composing cognitive science.

- We start off with a basic assumption common to all of the cognitive sciences. Then we show how different interpretations of that assumption generate different models of the mind.

- The basic assumption is that cognition is information processing. Information is the currency of cognitive science.

- The “information” in cognitive science has little to do with Shannon’s mathematical theory of information; the formal specification for information.

- Important questions regarding the basic assumption (only applicable to individual cognitive systems)

- In what format does a particular cognitive system carry information?

- How does that cognitive system transform information?

- How is the mind organized so that it can function as an information processor?

- A mental architecture is a set of answers to these three questions.

- We don’t want to assume that all cognitive systems carry and transform information in the same way, hence why we say “individual cognitive system”.

- E.g. pictures and text. Even though they are both represented by zeros and ones, the information doesn’t represent the same thing.

- It’s difficult to define what a cognitive system is without the notion of information processing. Whenever we have a cognitive system, we have some information processing function.

- This distinguishes cognitive systems from, say, anatomical systems. It’s why we can’t read off the organization of the mind from a brain atlas because there’s some hidden function.

- Domain-general: there are no limits to the types of information that can be processed.

- Modularity hypothesis (domain-specific) vs faculty-based hypothesis (domain-general).

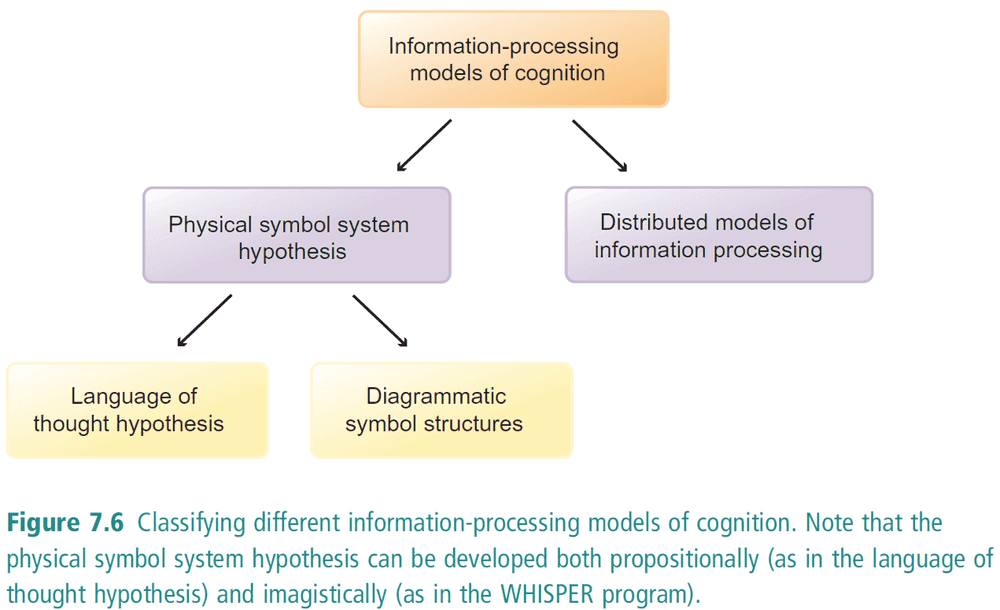

- Computational information processing paradigm (physical system hypothesis) vs connectionist information processing paradigm (artificial neural networks).

Summary

- The integration challenge can be tackled in a global manner.

- Global responses to the integration challenge seek to define relations either between different levels of explanation (intertheoretic reduction) or between different levels of organization (Marr’s tri-level hypothesis).

Part III: Information-Processing Models of the Mind

Chapter 6: Physical symbol systems and the language of thought

6.1 The physical symbol system hypothesis

- Physical symbol system hypothesis: A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means for general intelligent action.

- There are two claims here

- One, that nothing can be capable of intelligent action unless it’s a physical symbol system.

- Two, there isn’t any obstacle to constructing AI provided that it tackles the problem by constructing a physical symbol system.

- The hypothesis reduces intelligence down to symbol processing.

- Physical symbol systems definition

- Symbols are physical patterns.

- Symbols can be combined to form more complex symbol structures.

- Physical symbol systems contains processes for manipulating complex symbol structures.

- The processes for generating and transforming complex symbol structures can themselves be represented by symbols and symbol structures.

- E.g. A Turing machine.

- The symbols are the zeros and ones which represent on/off in electrical signals.

- The zeros and ones can be combined to form words and instructions.

- The Turing machine contains a table of instructions for processing zeros/ones that it sees.

- The table of instructions can be encoded as zeros and ones.

- An implication from the physical symbol system hypothesis is that thinking is the transformation of symbol structures according to rules.

- Problem solving can be thought (abstractly) as a process of searching through a search-space for a solution.

- Means-end analysis

- Evaluate the difference between the current state and the goal state.

- Identify a transformation that reduces the difference between the current state and the goal state.

- Check that the transformation in (ii) can be applied to the current state.

- If it can be applied, then apply it and go back to step (i)

- Else go back to step (ii)

- Means-end analysis is a general problem solving technique that shows up in many places. For example

- The back propagation algorithm

- Calculate error

- Calculate how to transform the weights via derivatives and chain rule

- Update the weights

- The quest for AI

- Calculate the difference by the games that an AI can beat humans at

- Apply research to game-playing AI

- Learn from failures, proceed with successes

- The back propagation algorithm

6.2 From physical symbol systems to the language of thought

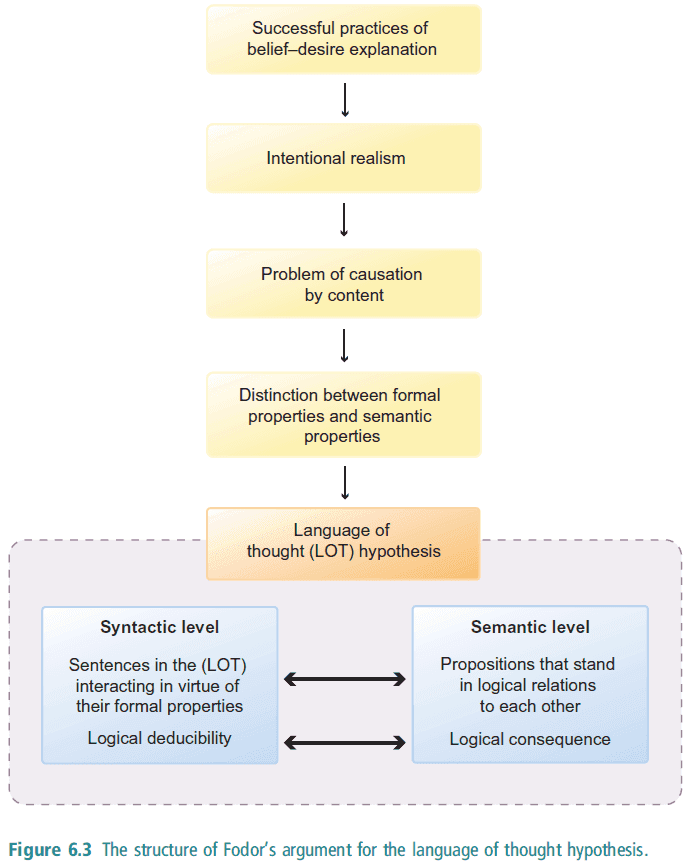

- Fodor’s language of thought hypothesis: the basic symbol structures in the mind that carry information are sentences in an internal language of thought.

- Propositional attitudes: the psychology states (E.g. fear, belief, happiness) that a person associates with a proposition (claim)

- Causation by content: the contents of a person’s beliefs and desires causes them to perform certain behaviors.

- The puzzle isn’t just how representations can cause behaviors, but that the contents of the representation can cause behaviors. In other words, how and why does meaning affect behavior?

- E.g. Reading a book can cause me to change my behavior, but how does the information that I read change my behavior? As a Turing machine, reading a symbol can change my state, but how and why does the specific symbol that I read change my state? Why is meaning significant?

- Fodor’s hypothesis solves the problem of causation by content.

- Formal properties: the physical properties that can be manipulated within brains.

- E.g. The letters of a language, the word “cat”, zeros and ones.

- Semantic properties: the properties by virtue of which representations represent.

- E.g. The word “cat” represents a furry and cute animal, certain combinations of zeros and ones represent text while others represent images.

- This gives us another way of putting our problem.

- How can the brain be an information processing machine if it is blind to the semantic properties of representations?

- How can the brain be an information processing machine if all it can process are the formal properties of representations?

- A computer can be programmed to manipulate strings of 0s and 1s in certain ways that yield the right result relative to the interpretation that is intended, even though the computer is blind to that interpretation.

- The manipulation of the strings is mechanical, only operating on its formal properties, but the manipulation does this in a way that respects the semantic properties.

- So, computers manipulate symbols in a way that is sensitive only to their formal properties while respecting their semantic properties.

- The analogy to the brain is that the brain manipulates the formal properties of mental representations while respecting the semantic properties of mental representations.

- Since brains and computers have to solve the same problem, and we understand how computers solve it, the easiest way to understand how brains solve it is to think of the brain as a kind of computer.

- Is this an artifact due to inventing computers before brains? What if we had neuroscience knowledge before computer science? Is it a coincidence that AI, computer science, and cognitive science got started at around the same time?

- Fodor’s claim of the computer model of the mind

- Causation though content is ultimately a matter of casual interactions between physical states.

- These physical states have the structure of sentences and their sentence-like structure determines how they are made up and how they interact with each other.

- Causal transitions between sentences in the language of thought respect the rational relations between the contents of those sentences in the language of thought.

- The medium of cognition is the language of thought. The language of thought is closer to logical languages than natural languages.

- The analogy between the language of thought and logical languages is at the heart of Fodor’s solution to the problem of causation by content.

- To provide a semantics for a language is to give an interpretation to the symbols it contains - to turn it from a collection of meaningless symbols into a representational system.

- Logical deducibility: when a deduction follows all of the rules

- Logical consequence: when a claim preserves truth (a true premise never leads to a false conclusion)

- Transitions between sentences in the language of thought can be viewed either syntactically or semantically, either in terms of formal relations holding between physical symbol structures or in terms of semantic relations holding between states that represent the world.

- E.g. of a syntactic transition, the word “cat” refers to a fluffy cute animal, but now I change it so that the word “cat” also refers to that fluffy cute animal.

- E.g. of semantic transition, the word “cat” refers to a fluffy cute animal, but now I change it so that the word “cat” also refers to that yellow, curved fruit.

6.3 The Chinese room argument

- John Searle challenges the claim that manipulating symbols is sufficient to produce intelligence behavior.

- Chinese room thought experiment

- Imagine a person in a room

- The person receives pieces of paper through one window and passes papers through another window

- The given paper has questions in Chinese

- The person has to answer those questions also in Chinese

- The person has a book that matches the question to an answer

- The person outputs the answer given by the book

- Searle argues that the Chinese room doesn’t understand Chinese. I disagree. Suppose instead of the room it were a living person that I was asking the questions to. If they provided reasonable responses to my questions, then I would confidently say that they know Chinese regardless of what happens internally.

- My main issue with the argument is who wrote the book that matches questions to answers? They must know and understand Chinese to have written it so thus the room acts as a proxy for them.

- Searle uses the example of the Chinese room to argue that there is a huge and impassable gap between formal symbol manipulation, on the one hand, and genuine thought an understanding on the other.

- The Chinese room argument is related to the Turing test; it rejects the Turing test as a measure of intelligent behavior.

- Symbol-grounding problem: how do symbols become meaningful?

- The symbol-grounding problem is a problem about how words and thoughts become meaningful to speakers and thinkers. The problem of intentionality is a problem about how words and thoughts connect up with the world.

- E.g. of the difference, the word “cat” refers to the fluffy cute animal because that’s how people speaking the language refer to that animal. This solves the problem of intentionality but not the symbol-grounding problem. It provides an account that the intention of “cat” refers to the animal, but it doesn’t say how that intention is formed.

- For this reason, the symbol-grounding problem is more fundamental than the problem of intentionality.

- One answer is that words in a language are meaningful for us because we attach meanings to them when we learn how to use them. But this just pushes the problem back.

- How do we learn that something is meaningful?

- The basic principle of cognitive science is that the mind works by processing information. If this information processing is symbolic, then the symbol-grounding problem immediately raises its head.

- We can either abandon the idea that cognition is a form of information processing (and with it abandon the idea that cognitive science can explain the mind). Or we can look for forms of information processing that are not symbolic.

Summary

- Mental architecture: combines a model of how information is stored and processed with a model of the overall organization of the mind.

- One model of how information is stored and processed is the physical symbol system hypothesis.

- The hypothesis states that a physical symbol system has necessary and sufficient means for general intelligent action. In more detail

- These symbols are physical patterns.

- Physical symbols can be combined to form complex symbol structures.

- Physical symbol systems contain processes for manipulating complex symbol structures.

- The processes for manipulating complex symbol structures can be represented by symbols and structures within the system.

- Problems are solved by generating and modifying symbol structures until a solution structure is reached.

- Rejections to this are the Chinese room argument, and more generally, the symbol-grounding problem.

- The symbol-grounding problem is a problem of how symbols become meaningful.

Chapter 7: Applying the symbolic paradigm

7.1 Expert systems, machine learning, and the heuristic search hypothesis

- Expert systems: a program that will reproduce the expert performance of human beings in a certain domain.

- Decision trees: a tree where each node is a question and each edge is an answer. The decision starts from the top and goes down as more questions are answered.

- Decision trees work because the questions exhaust the space of possibilities. Each fork reduces the possible nodes that can be reached at the bottom, thus partitioning the space of possibilities.

- We don’t want to hard code the tree, but rather have it learn which nodes and edges it should create by using past data.

- Heuristic search hypothesis: problems are solved by generating and modifying symbol structures until a suitable solution is found.

- We want a machine learning algorithm that will construct a decision tree from a collection of data. In other words, we kind of want it to program IF-THEN constructs and to find patterns in the data.

7.2 ID3: An algorithm for machine learning

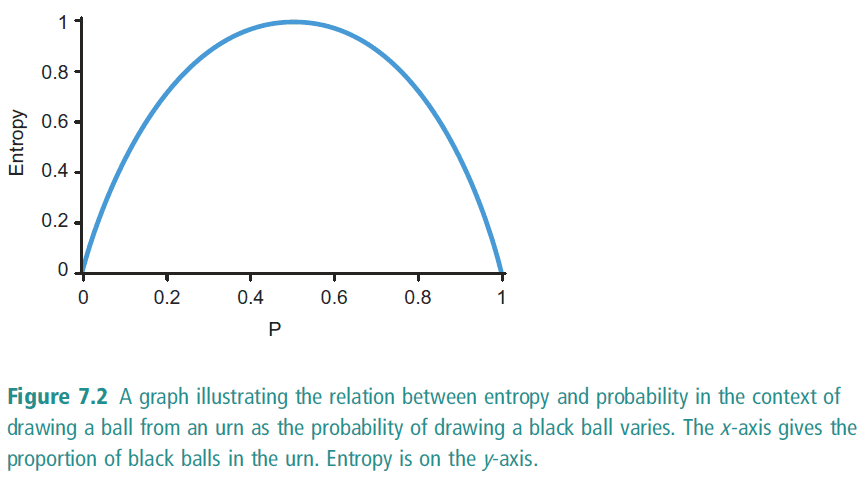

- Information gain: how much information we would get from that attribute or how much that attribute reduces uncertainty/entropy.

- The machine learning algorithm should generalize the hidden rules in data which can be used on new, incoming data. To convert from a database to a decision tree.

- The ID3 exploits the feature that each attribute divides the set of examples into two or more classes. It identifies, for each node in the decision tree, which attribute would be most informative at that point. In other words, which attribute has the greatest weighing on the outcome.

- This is determined by measuring how important the attribute is in determining the outcome by measuring the attribute’s information entropy.

- Information entropy is like a measure of uncertainty.

- This makes it seem like the ANNs right now are just overlapped decision trees with non-binary weighing.

- For each attribute of an example, the ID3 algorithm works out how well the attribute organizes the remaining examples.

- This is done by calculating how much entropy is reduced if the set were classified according to that attribute. If that attribute reduces entropy by a some amount, then we determine that that attribute plays some role in the outcome of the decision.

- By ranking the attributes in terms of entropy reduction, we can use the attribute that reduces the most entropy as the first decision node.

- We can continue this process for the next attribute until we run out of attributes.

- ID3 Algorithm steps

- Calculate the baseline entropy.

- Confirm that the target attribute doesn’t classify the examples well (i.e. it has a high baseline entropy).

- Calculate the attribute that gives the most information in making a decision.(i.e. the attribute that reduces the most uncertainty/has the highest information gain).

- Repeat step (iii) until the entropy is low enough to make a decision.

- Decision trees can be converted into a set of IF-THEN statements.

- The ID3 algorithm is an example of the physical symbol hypothesis because it transforms a highly complex symbol structure, the database, into a simpler symbol structure, the decision tree.

- The process of transforming inputs to outputs is essentially a process of manipulating symbol structures according to rules. The rules are the IF-THEN statements.

7.3 WHISPER: Predicting stability in a block world

- The physical symbol structures in the physical symbol system hypothesis doesn’t have to be language-like. They could be diagrams or images.

- There’s a dispute about which physical symbol structures are involved in particular types of information processing.

- This dispute is within the hypothesis, not whether the hypothesis is true or not.

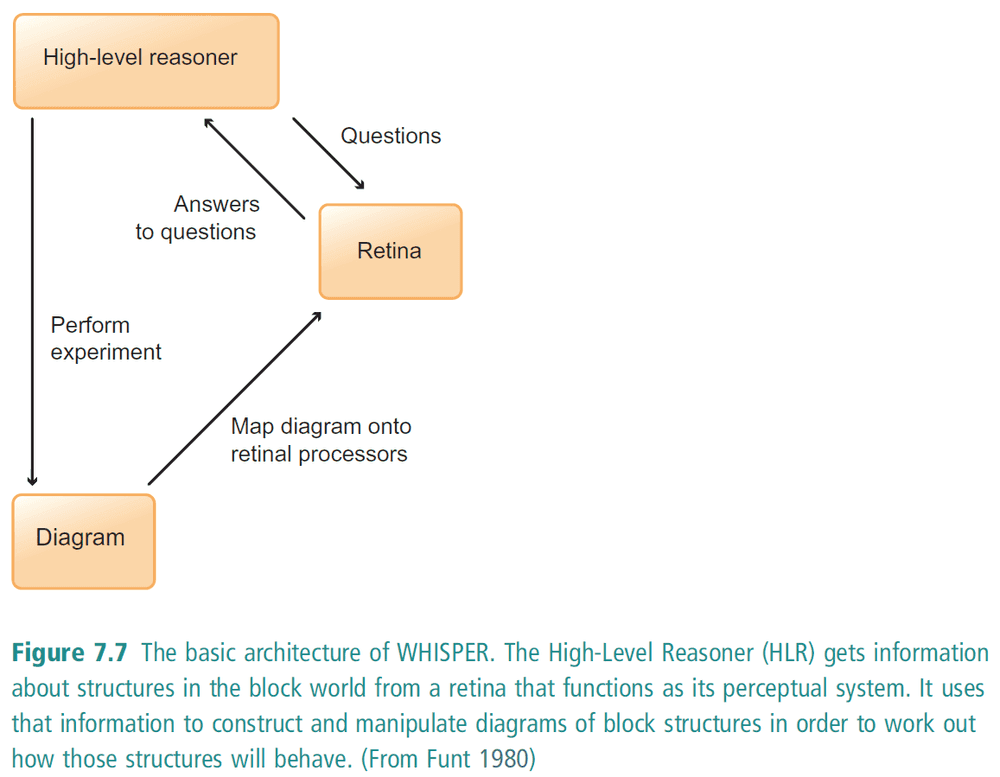

- WHISPER: a program to assess the stability of structures in the block world and then work out how unstable structures will collapse.

- WHISPER fits the heuristic search hypothesis because it starts with the problem and then transforms it into a solution.

- It has hard coded rules such as “an unstable object will rotate around the support point closest to its center of gravity.”

- Our main reason for looking at WHISPER isn’t that it succeeds in solving problems, it’s that it gives a clear illustration of just how wide-ranging the physical symbol system hypothesis can be.

- WHISPER shows that there are other ways of thinking about the physical symbol system hypothesis.

- Both ID3 and WHISPER solve problems by generating and modifying physical symbol structures until a solution structure is reached.

7.4 Putting it all together: SHAKEY the robot

- Now we try to see whether symbol manipulation can generate intelligent action in a real, physical environment.

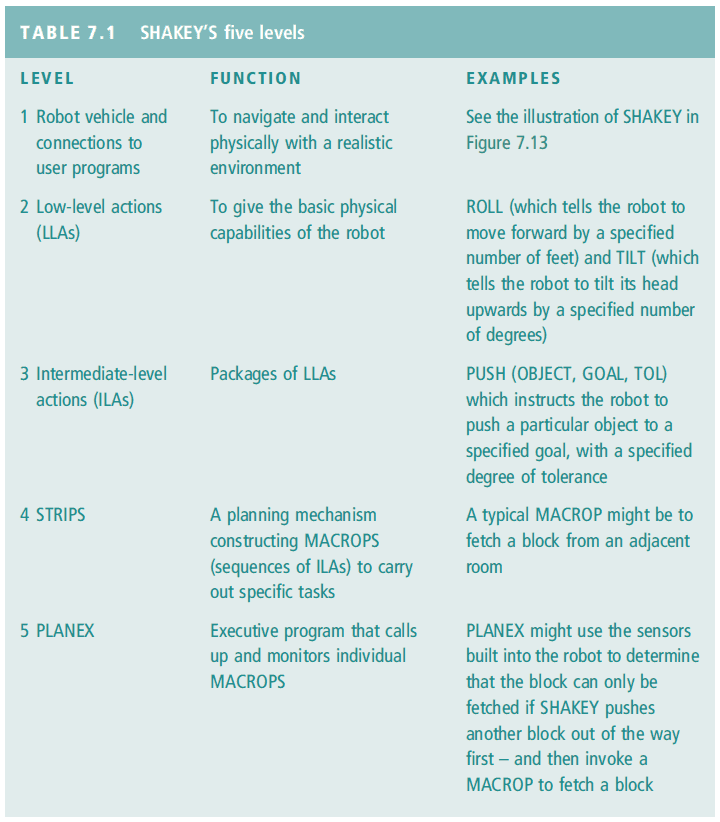

- SHAKEY is a robot that’s able to move around, perceive, follow instructions, and implement complex instructions in a realistic environment.

- The robot is programmed in first-order predicate calculus.

- Recall that behavior can be organized hierarchically, with the most complex behavior at the top and the simplest behaviors at the bottom (that don’t require any planning).

- SHAKEY’s software packages are built around this basic idea that complex behaviors are hierarchically organized.

- As we move up the levels, the more we turn from hardware to software.

- The levels are just like inheritance/abstraction in programming. Call the level below yours to perform a function and that levels does the same and so on.

- We can also call functions in the same level.

- We can think about SHAKEY’s planning process as a tree search. The top node is the current state and the branches are states that can be reached via transformations.

Summary

|ID3|WHISPER|SHAKEY|

|---|---|---|---|

|Symbols are physical patterns.|Attributes and values|Blocks and shapes|Symbols in predicate calculus|

|Symbols can be combined to form more complex symbol structures.|Database|Diagram|Formulas in predicate calculus|

|Physical symbol systems contains processes for manipulating complex symbol structures.|Decision tree

- IF-THEN statements

- Information gain

- Information entropy|Transformations

- Rotation

- Chain reaction

- Translation|Rules in predicate calculus or algorithms.|

|Problems are solved by generating and modifying symbol structures until a solution structure is reached.|Reach solution by using ranking and information gain to create an decision tree.|Reach solution by using transformations and propagating reactions to create a state of stability.|Reach solution by using tree search to find a deducible path to achieve the desired goal.|

- The ID3 algorithm operates on databases of information and uses those databases to construct decision trees.

- The WHISPER program shows that physical symbols need not be language-like, they can be imagistic.

- The SHAKEY robot illustrates how the physical symbol system can be used to control and guide actions in a physical environment.

- Expert systems are designed to reproduce the performance of human experts in particular domains.

Chapter 8: Neural networks and distributed information processing

8.1 Neurally inspired models of information processing

- Whereas the physical symbol system hypothesis is derived from the workings of digital computers, this new model of information processing is derived from the working of brains.

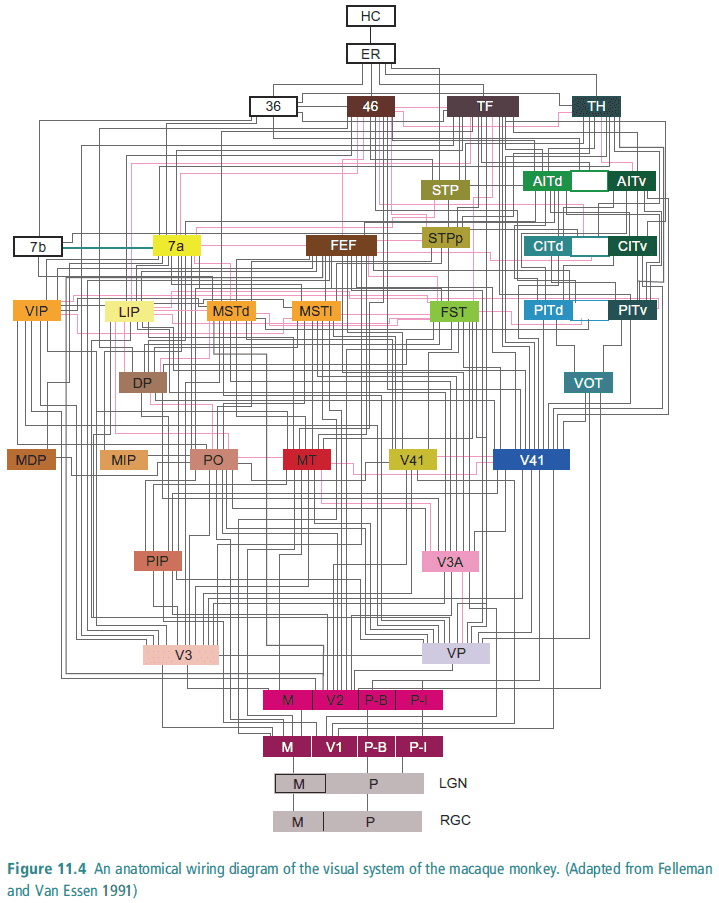

- The problems when studying the brain as an information processor is the resolution and scale. Neuroimaging techniques are too coarse while single neuron techniques are too fine.

- We need to know not just what particular regions of the brain do but also how they do it.

- We will not understand the brain until we understand what happens in each level of organization, from large scale brain areas to individual neurons.

- The fundamental feature of the brain is its connectivity.

- How do populations of neurons give rise to high levels of cognition such as perception and memory?

- In short, we do not have the equipment and resources to study populations of neurons directly.

- However, we can bypass this limitation by modeling that approximates populations of neurons.

- Computational neuroscience: modeling biological neurons and populations of neurons using mathematics.

- Neural network models are distinctive in how they store information, how they retrieve it, and how they process it compared to the physical symbol system hypothesis.

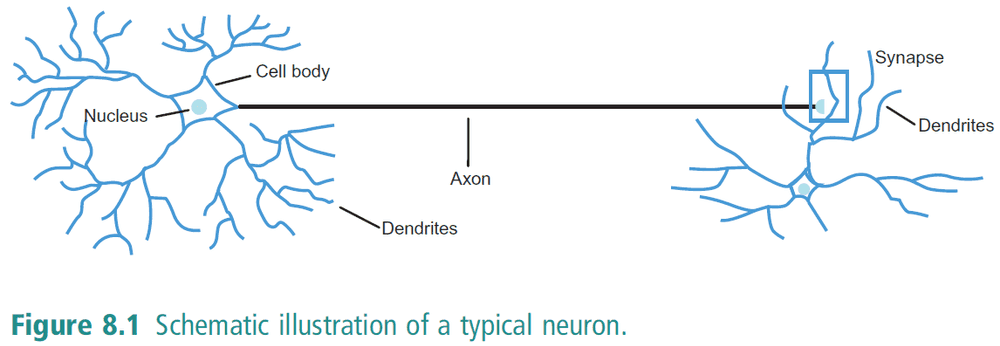

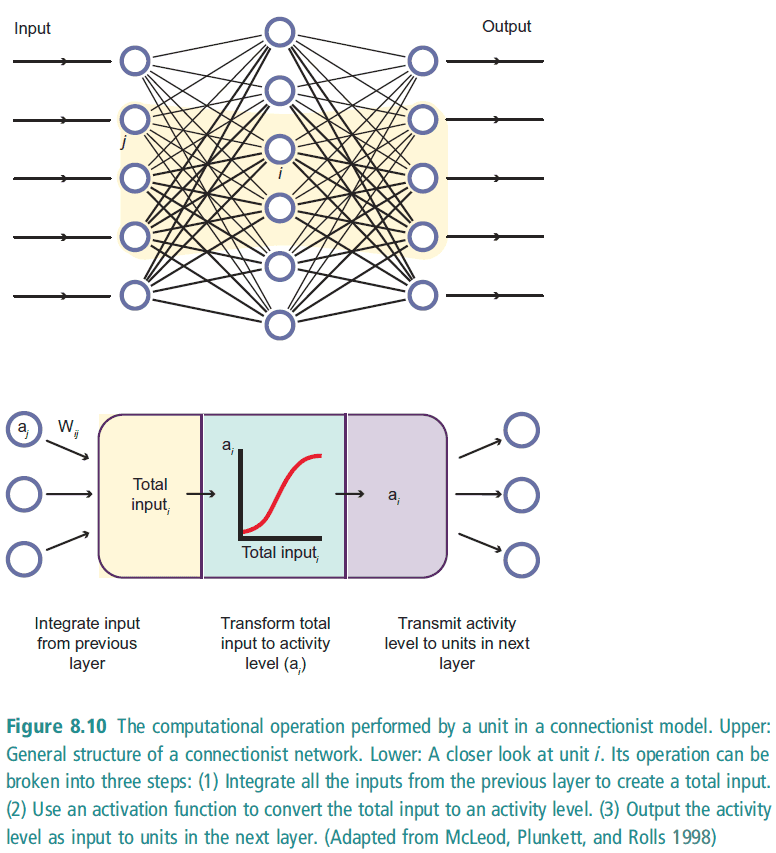

- The basic unit of a neural network is the neuron.

- Neurons might receive inputs from 10,000 to 50,000 neurons.

- The basic activity of a neuron is to fire an electrical impulse along its axon and to receive electrical impulses from its dendrites.

- The single most important fact about the firing of neurons is that it depends upon activity at the synapses.

- Some of the signals reaching the neuron’s dendrites promote firing and others inhibit it. These are called excitatory and inhibitory synapses respectively.

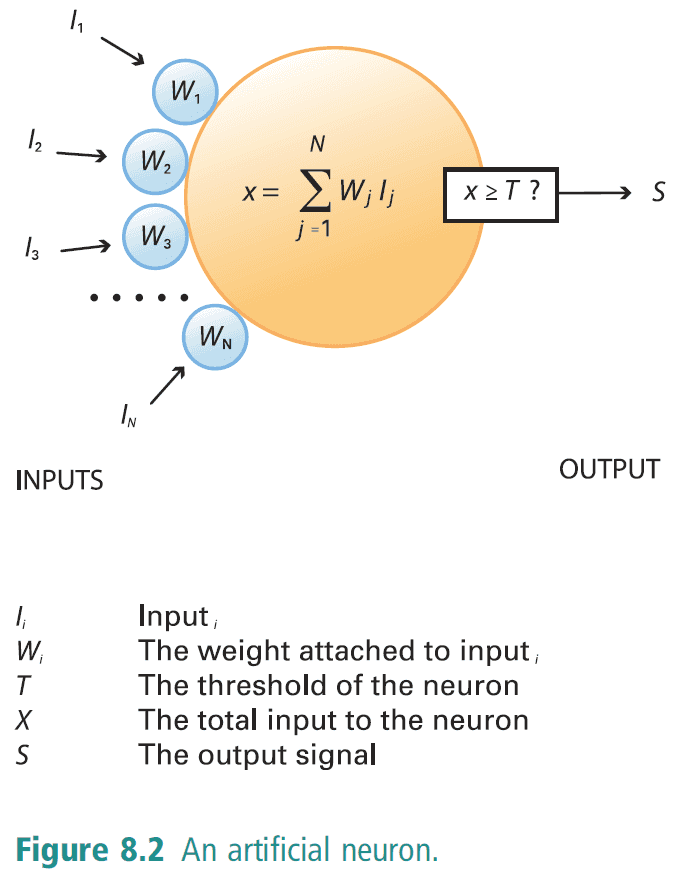

- If the total input exceeds the threshold (T) then the neuron “fires” and transmits an output signal.

8.2 Single-layer networks and Boolean functions

- Mapping function: a function that maps inputs to outputs where no input has more than one output.

- Binary boolean functions: inputs are pairs of truth values and outputs a truth value.

- E.g. AND, OR, XOR

- This is connected to neural networks because the network can be used to represent some of these binary Boolean functions.

- To represent the functions, we need to set the weights and the threshold in such a way that the network mimics the truth table for that Boolean function.

- Individual neurons are able to achieve a lot such as mimicking AND, OR, and NOT.

- By chaining together individual neurons into a network, artificial neural networks can do anything that can be done by a digital computer.

- A neural network can simulate a digital computer by simulating its logic gates.

- However, the key to getting neurons to represent Boolean functions lies in setting the weights and threshold. But how do we go about doing this?

- What makes neural networks such a powerful tool in cognitive science is that they are capable of learning. This learning can be supervised (when the network is “told” what errors it is making) or unsupervised (when the network does not receive feedback).

- The most important event in the development of neural networks was the discovery of a learning algorithm that could overcome the limitations of single-unit networks.

- Hebbian learning: learning is, at the bottom, an associative process. It’s also a form of unsupervised learning.

- Hebbian learning happens at the synaptic level where synapses are modified based on whether the postsynaptic neuron fires. Neurons that fire together, wire together.

- The process of learning (for a neural network) is the process of changing the weights in response to error.

- Perceptron convergence rule: a supervised learning that that learns by reducing error.

- Learning rate: how large the changes are on each trial.

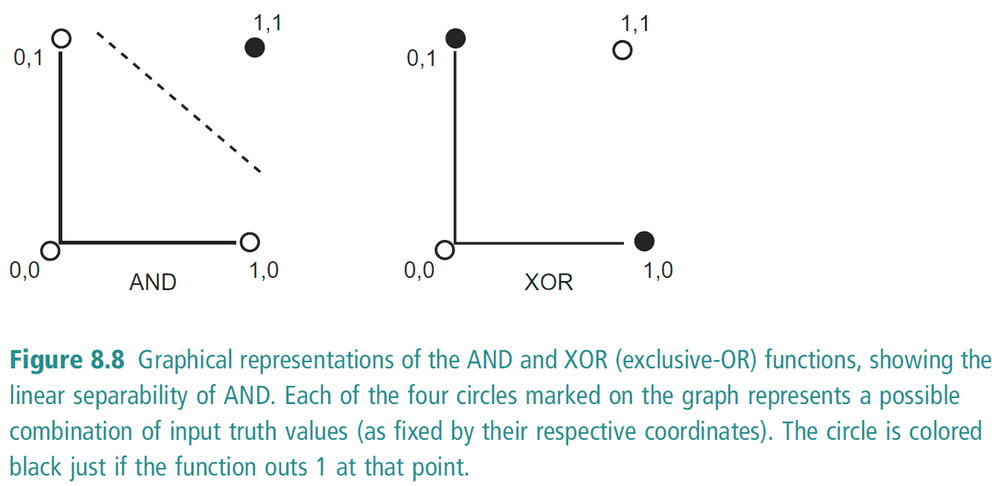

- Linearly separable: if the output space can be separated by a line.

- XOR cannot be represented by a single-layer neural network since its output space isn’t linearly separable.

- The class of Boolean functions that can be computed by a single-layer network is only the class of linearly separable functions.

- Hidden layer: a layer in the neural network that isn’t the input nor the output. It’s hidden from the outside world.

- Multilayered networks can compute any computable function - not just the linearly separable ones. The problem is how to train a multilayered network.

- The perceptron convergence rule cannot be applied to multilayer networks because there isn’t an error value for the hidden layers. With no way of calculating the error, we don’t know how to update the weights.

8.3 Multilayer networks

- Feed forward networks: the processing is forwards through the network.

- Backpropagation algorithm: the error is propagated backwards through the network from the output units to the hidden units.

- The backprop algorithm finds a way of calculating the error for a given hidden unit by using the following ideas

- Each hidden unit connected to an output unit bears a certain degree of responsibility for the error of that output unit.

- E.g. If the output is too low, then this was caused by a connected hidden unit whose output was too low.

- This gives us a way of assigning error to each hidden unit.

- Once we assign the degree of responsibility to a hidden unit, then we can modify the weights between that unit and the output unit to decrease the error.

- The error is propagated back through the network until the input layer is reached.

- It’s very important to remember that activation and error travel through the network in opposite directions. Activation spreads forwards through the network (at least in feed forward networks), while error is propagated backwards.

- How biologically plausible are neural networks? Here are some differences

- ANN units are all the same while the brain has many different types of neurons.

- Brains aren’t as parallel as ANNs.

- The scale of ANNs doesn’t compare with the brain. A single cortical column can contain 200,000 neurons whereas ANNs don’t have more than 5,000 neurons.

- There is no evidence that anything like the backpropagation of error takes place in the brain. Backprop is powerful because it can transmit the error information using “action at a distance” which doesn’t seem to happen in the brain.

- Local learning algorithms: biologically plausible learning algorithms.

- A unit’s weight changes directly as a function of the inputs and outputs of the unit.

- In terms of biological neurons, the information for changing the weight of a synaptic connection is directly available to the presynaptic axon and postsynaptic dendrite.

- E.g. Hebbian learning rule

- Competitive networks: neural networks that don’t require any feedback. Aka unsupervised learning.

- The key to competitive networks is that the output layer has inhibitory connections within its own layer. This allows the output units to compete with each other with the winner being rewarded by having its weights increased.

- This contrasts with feedforward networks because there aren’t connections within a layer (between units in the same layer).

- Competitive networks are good at classification which requires detecting similarities between different input patterns.

- E.g. recognizing the same object from many different angles and perspectives. This is known as position-invariant object recognition.

- A good neural network model should match closely with what we know about people.

8.4 Information processing in neural networks: Key features

- Instead of focusing on the details of neural networks, we now return to studying how neural networks process information.

- In the physical symbol system hypothesis, representations are distinct and identifiable because symbols are like that. The structure and shape of the physical symbol structure is directly correlated with the structure and shape of the information it is carrying.

- This contrasts with ANNs as the network stores information in its pattern of weights. It knowledge is distributed across the relative strengths of the connections between different units.

- In the physical symbol system hypothesis, all information processing is rule based. The rules are separate from the representations (symbols that the rules act on).

- This contrasts with ANNs as its rules are generalizable regardless of the input/output.

- E.g. To calculate the result of an AND statement, the physical symbol system hypothesis uses a Turing machine with explicit rules that only apply for AND. While an ANN can use the same network for AND and OR.

- The final key feature is that ANNs can learn / be updated while physical symbol systems cannot.

Summary

- Artificial neural networks (ANN) are constructed from individual units that function as highly idealized neurons.

- Train single-layer networks using the perceptron convergence rule.

- Train multi-layer networks using the backpropagation algorithm.

- Single-layer networks can computer linearly separable Boolean functions such as AND, OR, and NOT.

- Multi-layer networks can compute any function.

- The backpropagation isn’t biologically plausible as error isn’t propagated backwards in the brain.

- Competitive networks are a form of unsupervised learning that learns only from its inputs and outputs.

- ANN key features

- Distributed representations (across units and weights)

- No clear distinction between information storage and information processing

- The ability to learn from experience

Chapter 9: Neural network models of cognitive processes

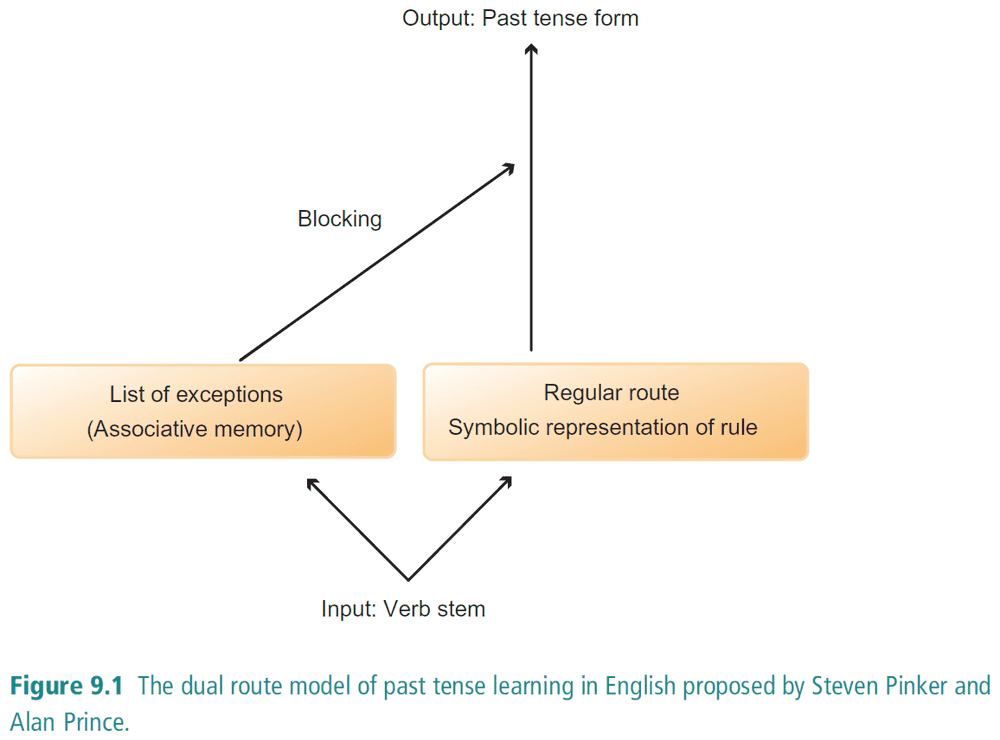

9.1 Language and rules: The challenge for information processing models

- It’s remarkable that all children manage to arrive at about the same level of linguistic comprehension and language use.

- Language is a rule-governed activity. It has grammatical rules.

- This section focuses on how the physical symbol system hypothesis is the only way of making sense of language.

- What is it to understand a language?

- There are two different dimension of linguistic comprehension

- Understanding what words mean

- Understanding the rules by which words are combined into sentences

- The basic unit of communication isn’t the word, but rather the sentence.

- The default hypothesis is that understanding a language is fundamentally a matter of mastering rules.

- E.g. Mastery of the rule that governs a word’s application such as only using “cat” to refer to a four-legged animal that’s fluffy.

- To understand language, users would need to be able to distinguish applications of the word that fit the rule from applications that do not.

- An alternative view is that to understand language, users use words in accordance with the rule because they somehow manage to compare possible sentences with their internalized representations of the rules.

- The more important you believe in explicit representations of rules, the more likely you’ll believe that language processing is done by the physical symbol hypothesis (because it depends upon rules being explicitly represented).

- The question of how languages are learnt is closely related to the question how what it is to understand a language.

- Truth rules: rules that state how words contribute to determining if a sentence is true.

- E.g. “Felicia is tall” is true just if X is G where X is a thing and G is a property.

- Fodor argues that learning a language has to involve learning truth rules. But which language are truth rules formulated in?

- You cannot use the language that you are learning to learn that language. Much like how a compiler cannot be written in the language it’s meant to compile. But bootstrapping.

- Language understanding isn’t purely theoretical so what does the evidence say?

9.2 Language learning in neural networks

- ANNs can model complex linguistic skills without having any explicit linguistic rules encoded into them.

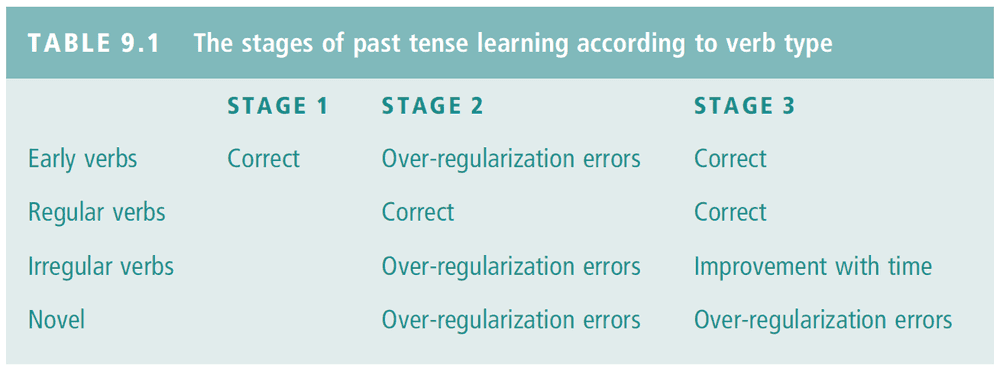

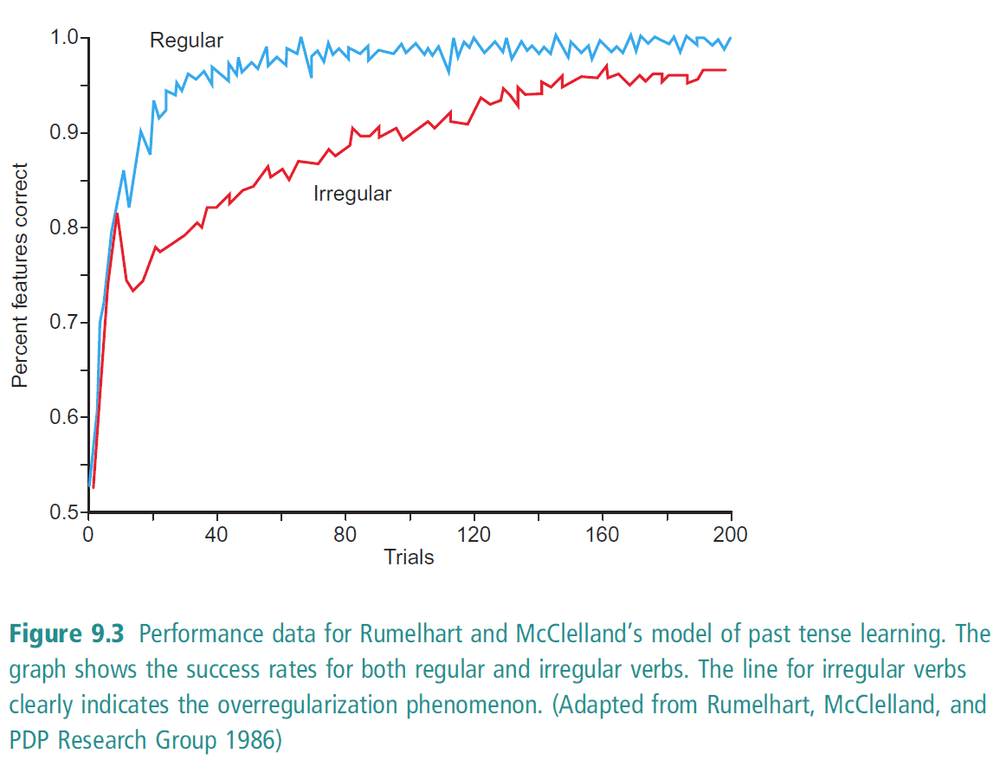

- When children learn languages, they display a very typical trajectory.

- E.g. Children make very similar types of errors at similar stages in learning grammar.

- Regular verbs: verbs that you add “-ed” to make it past tense.

- Irregular verbs: verbs that aren’t regular. E.g. take/took, bring/brought.

- When children learn these verbs, they go through three principle stages.

- First stage

- Small number of common but irregular verbs

- Learnt through role memorization

- Not able to generalize

- They can’t do much, but what they do, they do well.

- Second stage

- Greater number of verbs (most of which are regular)

- Surprising that children take a step backwards. They commit over-regularization error such as “gived” instead of “gave”.

- Third stage

- Cease to make over-regularization errors

- Still improve their command of regular verbs

- The theory (using physical symbol hypothesis) is that the second stage learning of regular verbs overrides the previously learnt rules on the irregular verbs.

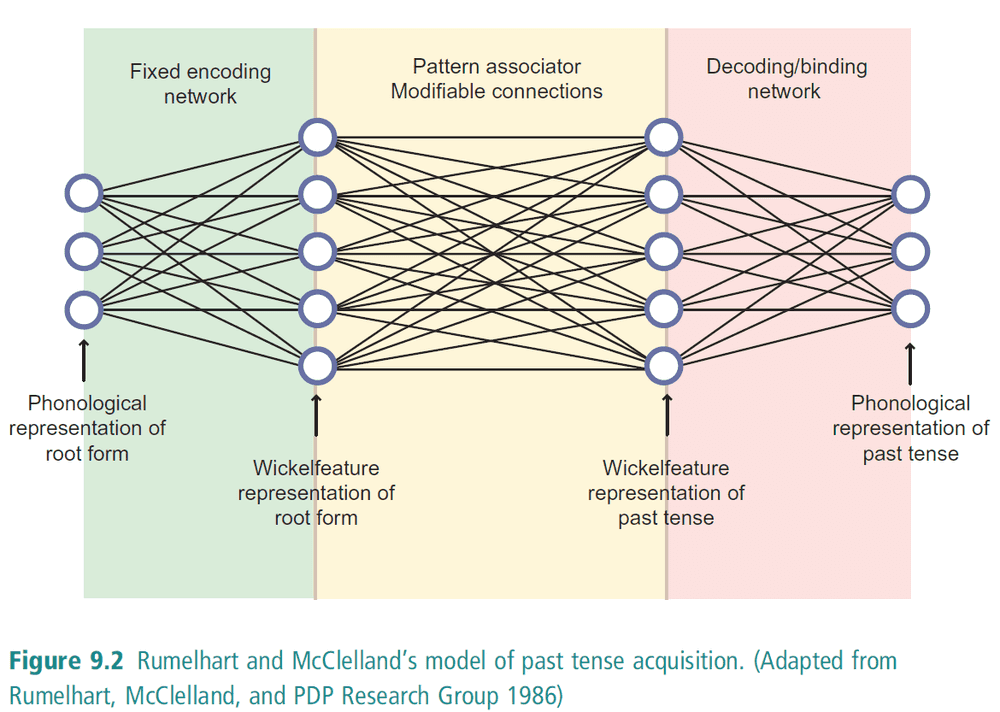

- A neural network that learns tenses

- Wickelfeature representation: a representation that codes phonetic information about individual phonemes within a word and their context.

- The first network is fixed. It doesn’t change or learn.

- The second network is a simple pattern associator that learns using the perceptron convergence rule.

- The third network is also fixed and is essentially a reverse of the first network.

- A significant feature of the network is that it reproduced the over-regularization phenomenon seen in children.

- ANN models of language acquisition are deeply controversial.

- The aim of neural network modeling isn’t to provide a model that faithfully reflects every aspect of neural functioning, but rather to explore alternatives to dominant conceptions of how the mind works.

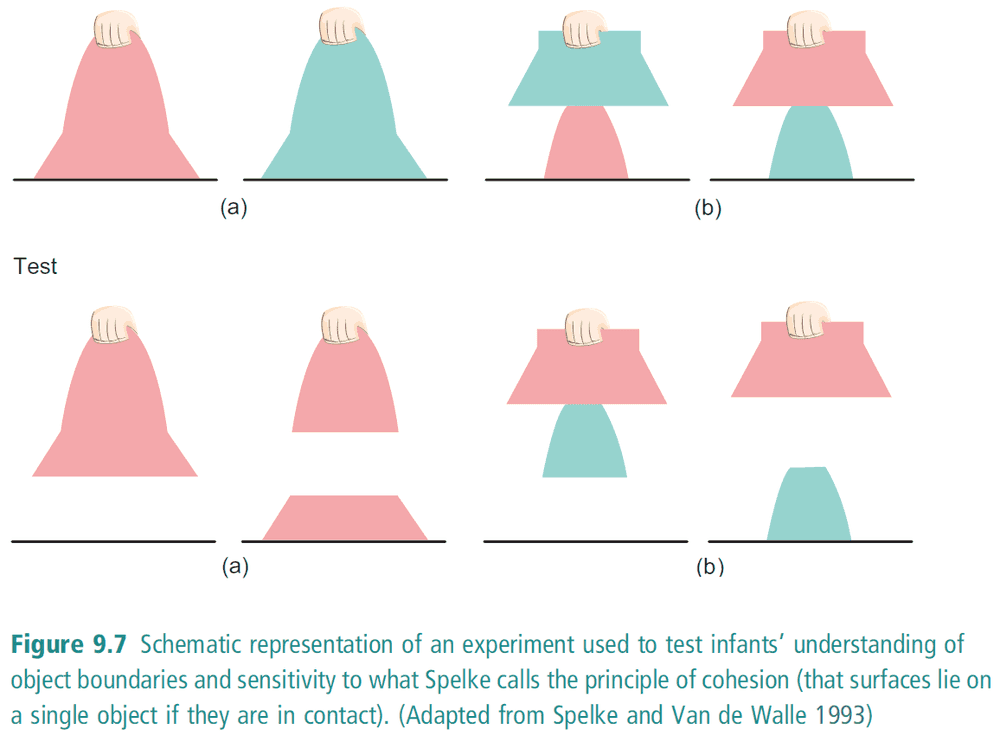

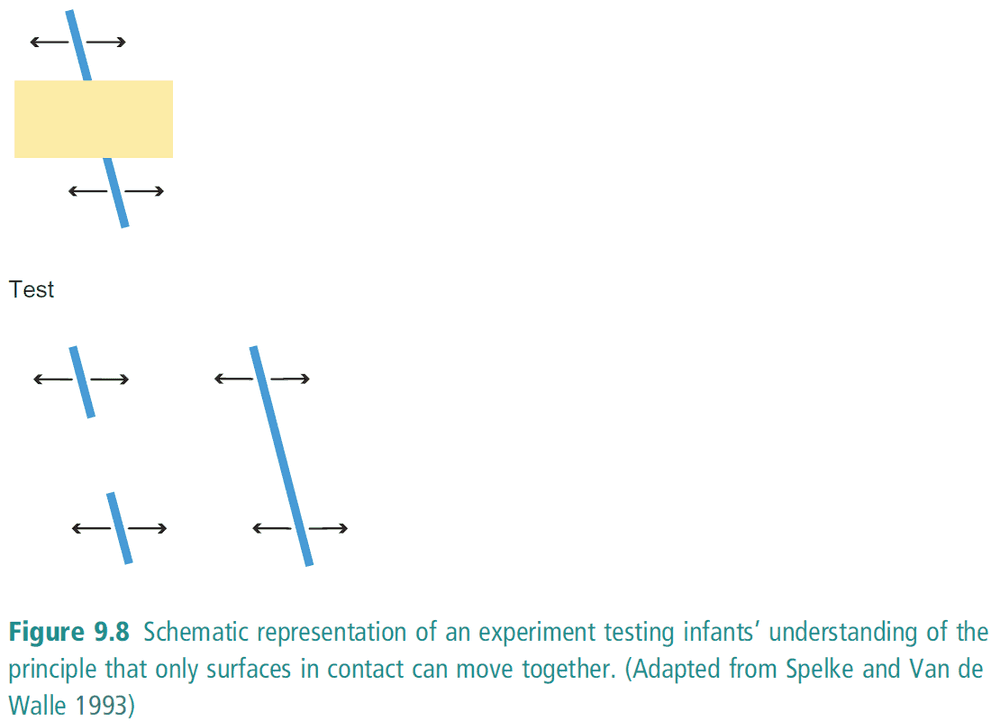

9.3 Object permanence and physical reasoning in infancy

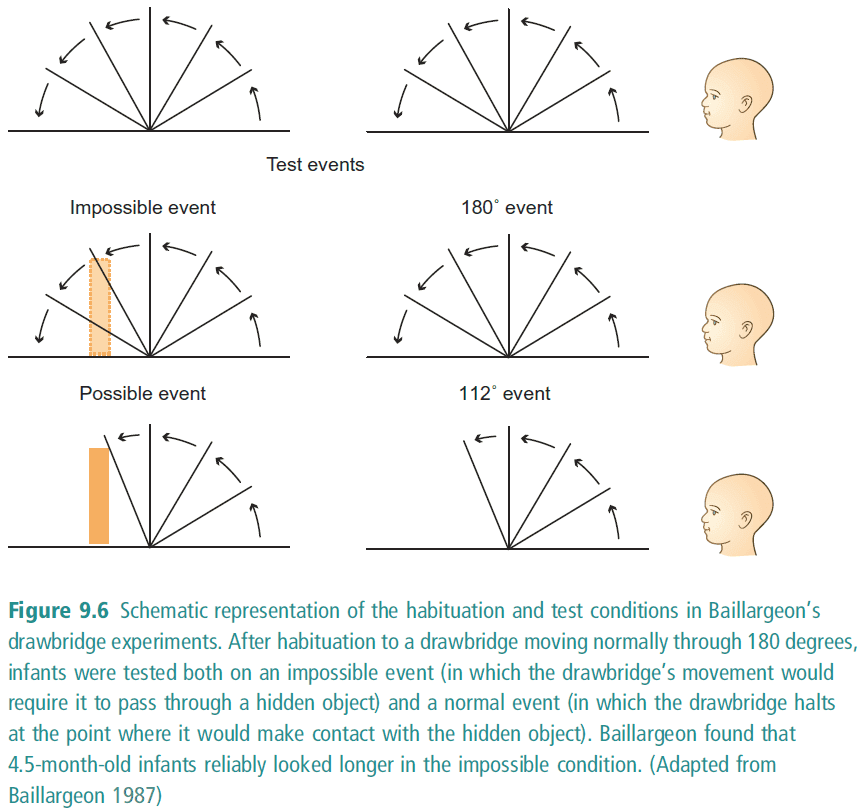

- We assume that infants look longer at events that they find surprising.

- So by measuring the amount of time that infants look at events, experimenters can work out which events infants find surprising (which also provides us info on what infants expect).

- Dishabituation paradigm: the way of identifying when a “violation of expectation” occurs.

- Object permanence: understanding that objects exists even if they aren’t seen

- When do children learn object permanence?

- This experiment and others seems to suggest that very young infants have an understanding of the basic principles governing how physical objects behave and interact.

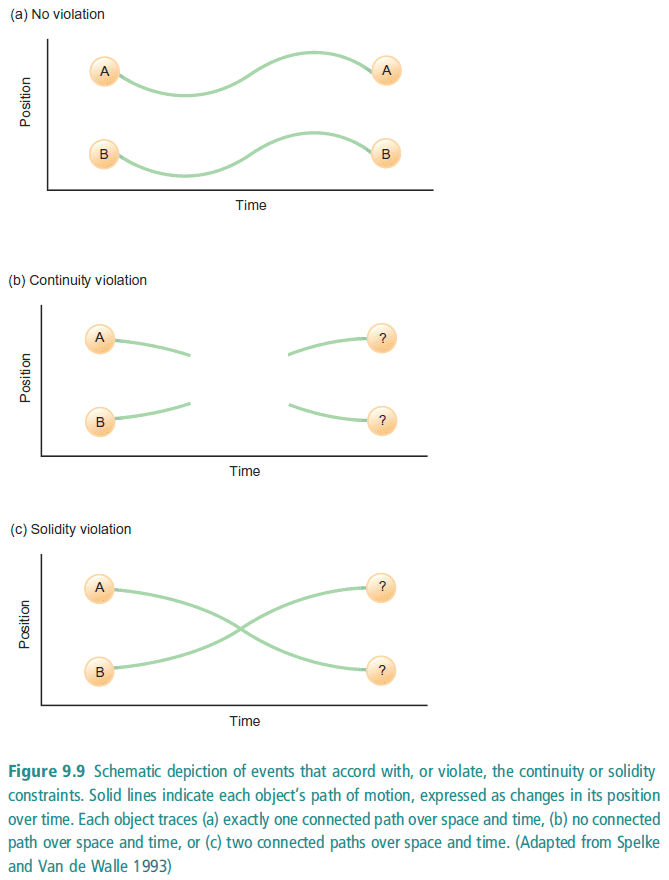

- The four basic principles of physical reasoning

- Principle of cohesion: surfaces that are touching are one object

- Infants show more surprise when the object comes apart, even if the object looks uniform.

- Principle of contact: only surfaces that are in contact can move together

- Infants show more surprise when both objects are moving but aren’t in contact with the each other

- Principle of solidity: two or more objects cannot occupy the same space and time

- Principle of continuity: objects don’t disappear

- These experiments show that infants have these principles on how objects behave and use these principles to make predictions. They show surprise when the prediction isn’t what happens.

- In a way, infants act like scientists in that they make inferences about things that they cannot see on the basis of the effects that they can see.

- What sort of information processing underlies this infant physics?

- In the physical symbol hypothesis, the principles are represented as rules.

- One important difference between infant physics and adult physics is the emphasis on spatiotemporal continuity versus featural continuity.

- Spatiotemporal continuity: the movement of an object is consistent in space and time

- E.g. A bee will always follow a path and never teleport or jump in time

- Featural continuity: the features and properties of an object is consistent

- E.g. A bee will remain a bee and not turn into a wasp

- Infants emphasize spatiotemporal continuity over featural while it’s the opposite for adults.

- Similar to the case of grammar, object physics also has rules and both can be modeled by the physical symbol hypothesis.

9.4 Neural network models of children’s physical reasoning

- Likewise to learning past tense, a neural network can simulate the behavior of infants in experiments on the dishabituation paradigm (without explicit rules being coded).

- It’s unfounded to conclude that infants actually access and reason using the object principles even though we believe it results in their behavior. It’s unfounded to attach a cause to an effect without ruling out the alternatives.

- One alternative is constructing an ANN that behaves as if it has the principle of continuity even though it wasn’t encoded with it.

- According to the neural network approach, dishabituation paradigms are essentially associative mechanisms of pattern recognition that are learnt over repeated exposure.

- E.g. For object permanence, there are two groups of neurons, one group fires before an object is hidden and the other fires when the object reemerges. This is strengthened over repeated exposure.

- One advantage of this approach is that it explains why infants ability to search for hidden objects lags behind their perceptual sensitivity to object permanence.

- An ANN has to learn to represent an object even when the object cannot be directly seen.

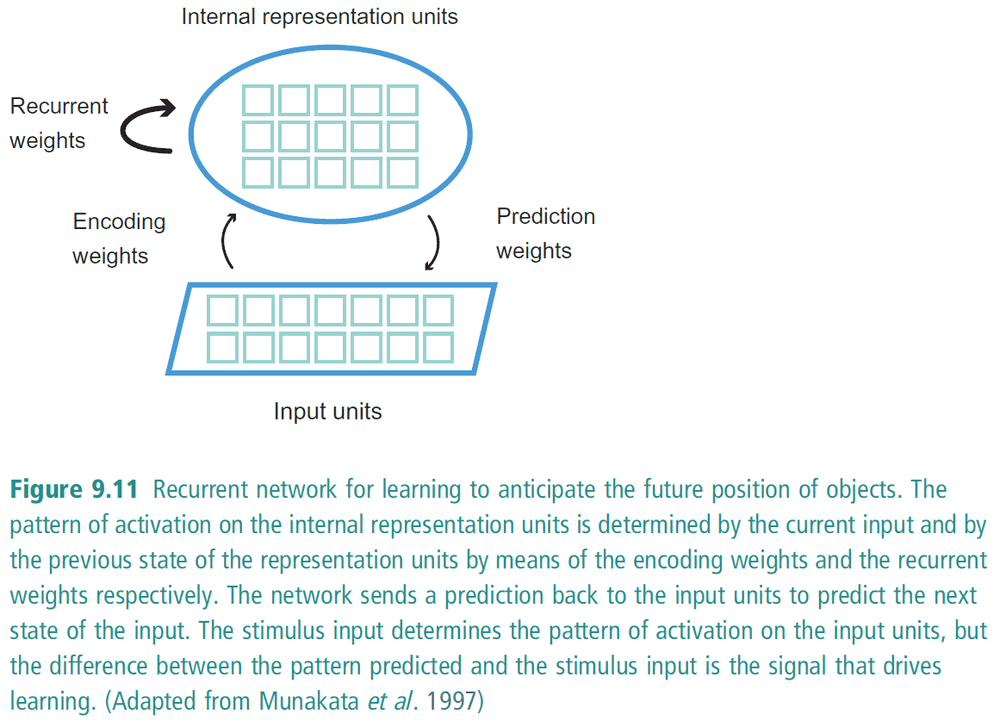

- One kind of neural network that can solve this is a recurrent neural network.

- Recurrent neural network: ANNs that have a feedback loop that transmits activation from the hidden units back to themselves. This transmission works before the learning rule is applied, thus the loop acts as a sort of memory for the ANN.

- The level of activation at any given temporal stage is determined by two factors

- The pattern of activation in the input units.

- The pattern of activation in the hidden units at a previous temporal stage.

- The second factor is crucial for learning object permanence.

- Learning is done using the backprop algorithm. The error is calculated by determining the difference between the actual input and the predicted input.

- In theory, the recurrent weights will tell the network that an object exists even when it isn’t seen as the weights will have “memory” of the object.

- In practice, improved sensitivity to object permanence is directly correlated with the hidden units representing the object the same when it is visible and when it’s hidden.

- In other words, memory is strong enough to explain object permanence.

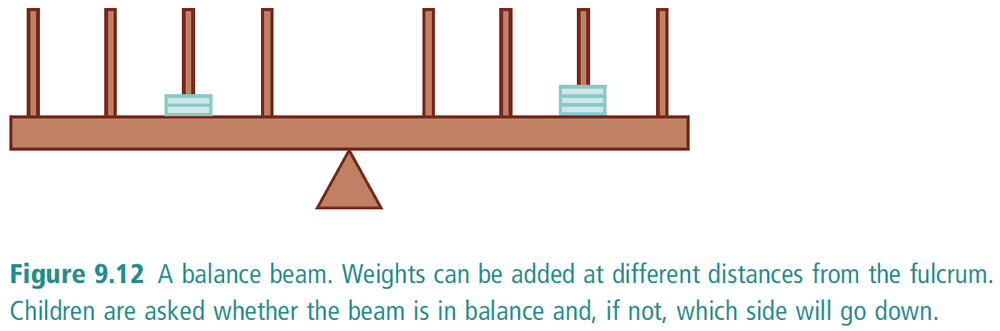

- Another test of physical reasoning is the balance beam problem

- This problem is similar to what WHISPER was designed to solve (section 7.3).

- What needs to be worked out is how different forces will interact.

- When children are shown this problem, they tackle it in four stages (similar to learning past tense of verbs.

- First stage

- The side with the greatest number of weights will go down regardless of how they’re arranged.

- Only accounting for number of weights.

- Second stage

- if both sides have equal number of weights, then the side with weights furthest from the center will go down.

- If not equal number of weights, then use the first rule or guess.

- Only using distance in specific case.

- Third stage

- Uses the correct rule that downwards force is a function of both weight and distance from the center.

- However, children can only apply this when the two sides differ in respect to either the weight or distance, but not to both.

- Fourth stage

- Usually not until adolescence that children gain a general competence for balance beam problems.

- Even then not all of them do.

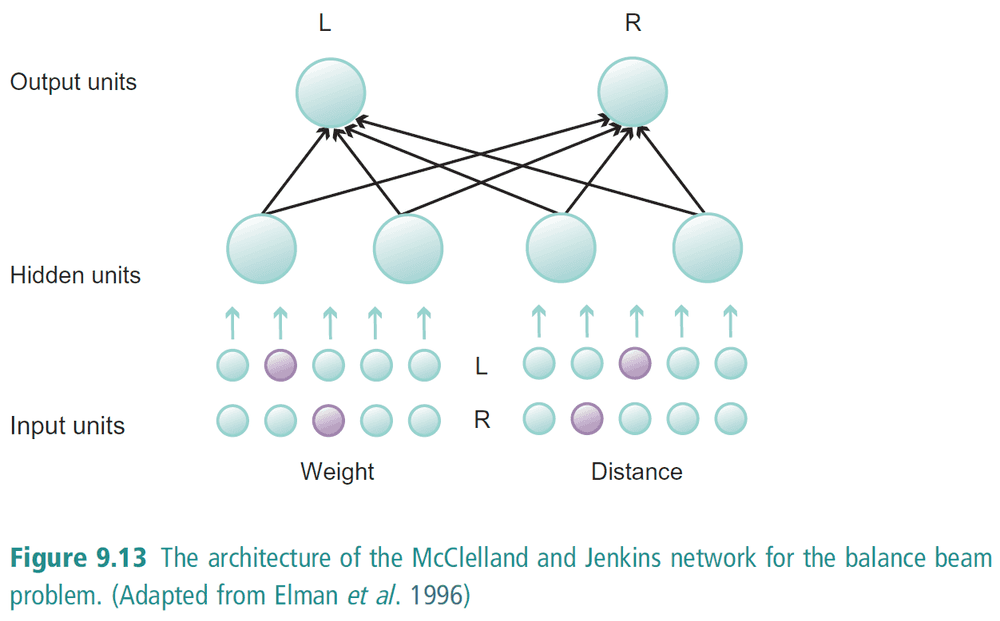

- It’s plausible to model the child’s learning using the physical symbol hypothesis, but also the ANN model.

- Even though children progress through a series of stages and their performance can be characterized in terms of progression of rules, it doesn’t follow that the cognition systems behind the processing takes the form of a rule-based architecture.

- E.g. ANN to solve this problem

- It’s important to realize that the information the network gets is actually quite impoverished.

- The ANN has to figure out that the two groups of units are carrying information about the same side of the balance beam.

- The ANN predicts that the balance beam will come down on the left hand side when the activation on the left output unit exceeds the activation on the right output unit.

- Learning is done using the backprop algorithm. The error is calculated by determining the difference between the actual output and the correct output.

- As the ANN trained, it went through a sequence of stages similar to that of children learning the task.

- Like tense learning, the progress on this problem can be characterized by a step-like progression.

- In the physical symbol hypothesis, the progression to a different stage would be explained by the transition from one rule to another.

- However, step-like progression can also emerge without the ANN learning explicit rules.

9.5 Conclusion: The question of levels

- ANN models have an ability to model the complicated trajectories by which cognitive abilities are learnt.

- In this section, we look into some concerns regarding ANN modeling.

- The physical symbol hypothesis aims at Marr’s second level, the algorithmic level, but has to be supplemented by an implementation.

- Where do ANNs fit in Marr’s tri-level hypothesis?

- ANNs will only count as alternatives to physical symbol systems if they turn out to be algorithmic-level accounts.

- ANN dilemma is that either ANNs contain representations with separable and recombinable components or they don’t.

- If they do, then they aren’t alternatives to the physical symbol hypothesis and are simply implementations of physical symbol systems.

- If they don’t, then they can’t be algorithmic-level models of information processing.

- Regardless, ANNs are not competitors to the physical symbol system hypothesis.

- This argument comes off as begging the question.

- In any case, cognitive scientists can be open minded to the nature of information processing as there isn’t any law regarding this.

- Language learning and physical reasoning are in many ways much closer to perception and pattern recognition than to abstract symbol manipulation.

- It may turn out that different types of cognitive task require fundamentally different types of information processing.

- Maybe a combination of both is what’s needed which is what the next part is on, a hybrid architecture.

Summary

- One of the great strengths of neural networks is that they are capable of learning.

- The development of cognitive abilities (such as learning past tense and object interactions) can be studied as a series of steps.

- These steps can be modeled using the physical symbol system hypothesis or using an artificial neural network model.

Part IV: The Organization of the Mind

Chapter 10: How are cognitive systems organized?

10.1 Architectures for intelligent agents

- AI aims to build intelligent agents.

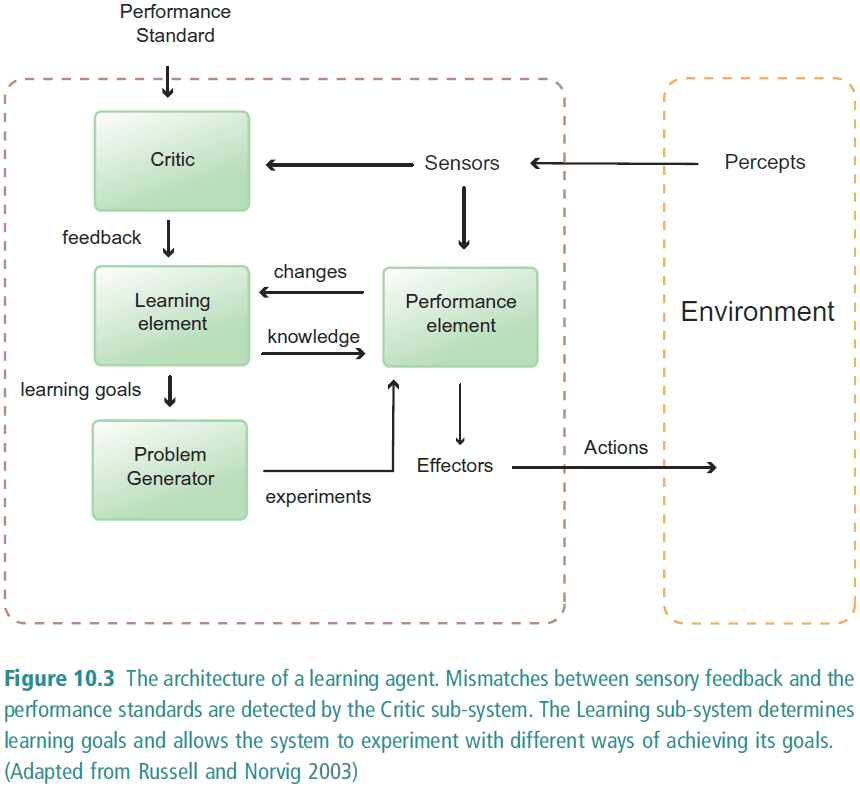

- Agent: a system that perceives its environment through sensory systems and acts upon that environment through effector systems.

- E.g. A robotic agent like SHAKEY

- Agent architecture: a blueprint that shows the different components that make up an agent and how those components are organized.

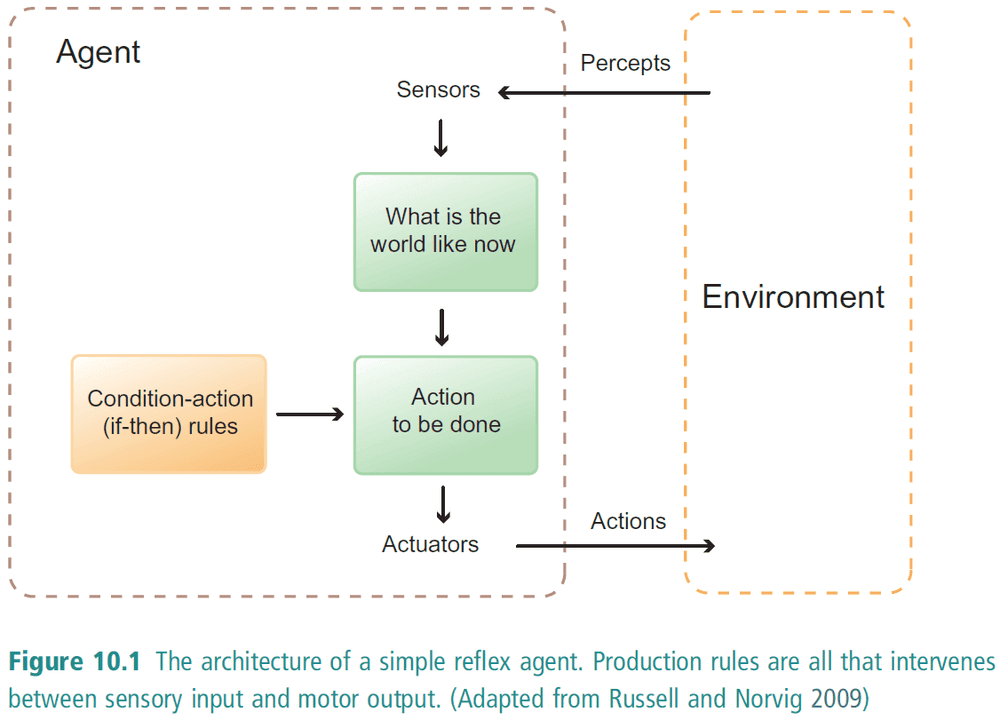

- Three different types of agent architectures

- Simple reflex agent

- Goal-based agent

- Learning agent

- What distinguishes different types of agents is the complexity between its sensory systems and its effector systems.

- Simple reflex agent: there are direct links between the sensory and effector systems.

- The direct links are achieved by condition-action/production rules (IF-THEN).

- Reflex agents aren’t cognitive agents because they don’t process information between sensory input and motor output.

- Goal-based agent: has goals and works out the consequences of different possible actions to achieve those goals

- However, these goal-based agents have no capacity to learn from experience.

- Learning agent: an agent that learns from experience

- Questions regarding modules

- How can we identify and distinguish modules?

- Do all of the modules process information in the same way? Do they all have the same representations?

- How “autonomous” and “insulated” are the different modules?

10.2 Fodor on the modularity of mind

- Cognitive module: a module (specialized sub-systems) that carries out an information processing task.

- E.g. Color perception, face recognition, and shape analysis

- Cognitive scientists think of the mind as an organized collection of specialized modules carrying out specific information processing tasks.

- An alternative view is that all of cognition is done by a single mechanism.

- Horizontal cognitive faculties: domain-general faculties that are applicable regardless of the input.

- E.g. Any form of information can be retained and recalled. Anything that can be perceived is a candidate for attention.

- Vertical cognitive faculties: domain-specific faculties that are only applicable to certain types of tasks.

- E.g. Analyzing shapes and recognizing faces.

- Vertical cognitive faculties are also information encapsulated meaning they only use a limited range of information.

- Cognitive modules = vertical cognitive faculties

- Cognitive modules have four main characteristics

- Domain-specificity: highly specialized mechanisms that carry out very specific tasks

- Informational encapsulation: processing is unaffected by other parts of the mind and cannot be infiltrated by background knowledge

- Mandatory application: response is automatic and cannot be under executive control

- Speed: transforms input to output quickly and efficiently

- Two further features

- Fixed neural architecture: there’s a corresponding brain area associated with the module

- Specific breakdown patterns: processing failures are highly determinable and predictable

- These two features are separate because they deal with how a cognitive module maps onto a specific part of the brain. This may or may not be true.

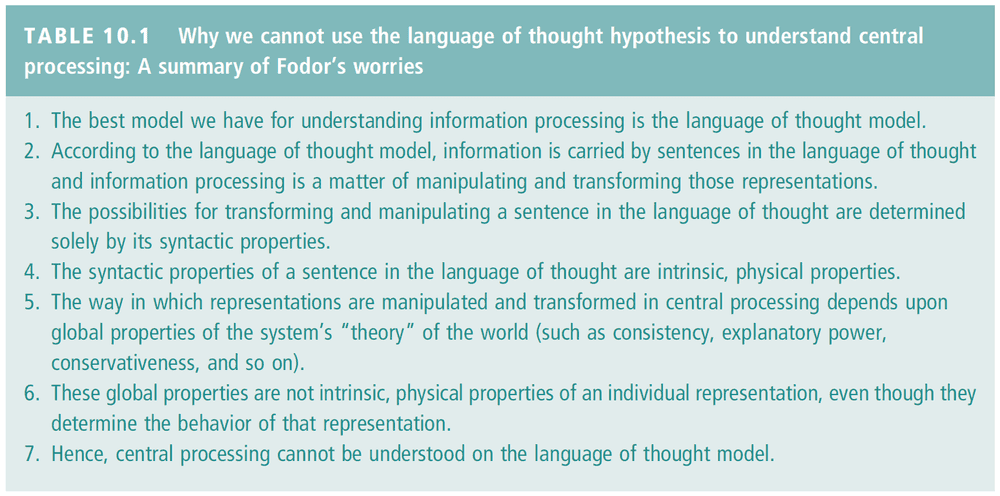

- Central processing how two distinguishing features

- Quinean: aims at certain knowledge properties that are defined over the propositional attitude system as a whole.

- Isotropic: not informationally encapsulated.

- E.g. Problem solving, understanding jokes, creativity.

- Fodor’s First Law of the Nonexistence of Cognitive Science: the more global a cognitive process is, the less anybody understands it.

- Arguments against Fodor’s claim

- Reject that the language of thought model is the best model for understanding information processing. We have ANN models that do just as well

- Reject that there are domain-general forms of information processing

- Reject that central processing exists and replace it with the massive modularity hypothesis

- I think that both modularity and central processing exist. Modules exist because we have different parts of the brain devoted to different functions. Central processing exists because different sense can use the same knowledge gained from a different sense.

- E.g. Memory, learning, and eye-hand coordination is general. The difficultly of AI is related to this.

10.3 The massive modularity hypothesis

- The belief that all information processing is modular.

- People are better at deontic conditions (permissions, requests, entitlements, etc.) than non-deontic conditionals.

- The explanation for this is because we have a specialized “cheater” detection module that developed over the course of evolution.

- Darwinian modules: specialized modules that evolved to solve a specific set of problems that our ancestors confronted.

- E.g. Cheater detection, kin detection, mate selection.

- Prosopagnosia: face blindness, can’t recognize faces.

- Prosopagnosia is an example of cognitive module.

- Two arguments by Cosmides and Tooby against central processing

- Argument from error

- Argument from statistics and learning

- Argument from error: domain-general cognitive modules couldn’t have been select by natural selection because they would have make too many mistakes. And they would’ve made too many mistakes because there isn’t an obvious error signal for a general module.

- Argument from statistics and learning: domain-general architectures are limited in the conclusions that they can reach. They are limited because domain-general modules couldn’t pick up on statistical generalizations such as Hamilton’s kin selection law.

- Poverty of the stimulus argument: certain types of knowledge must be innate because the stimuli that we encounter are too impoverished to allow us to acquire that knowledge.

- Arguments against the massive modularity hypothesis

- The input to a module must be filtered, and if this filtering is done by a module, then what is being inputted into the module? At some point, the input must be domain-general information thus not modular.

- How to combine the outputs of different modules?

10.4 Hybrid architectures

- Symbolic paradigm: physical symbol system hypothesis

- Distributed paradigm: artificial neural networks

- The distinction between physical symbol systems and ANNs isn’t all or nothing.

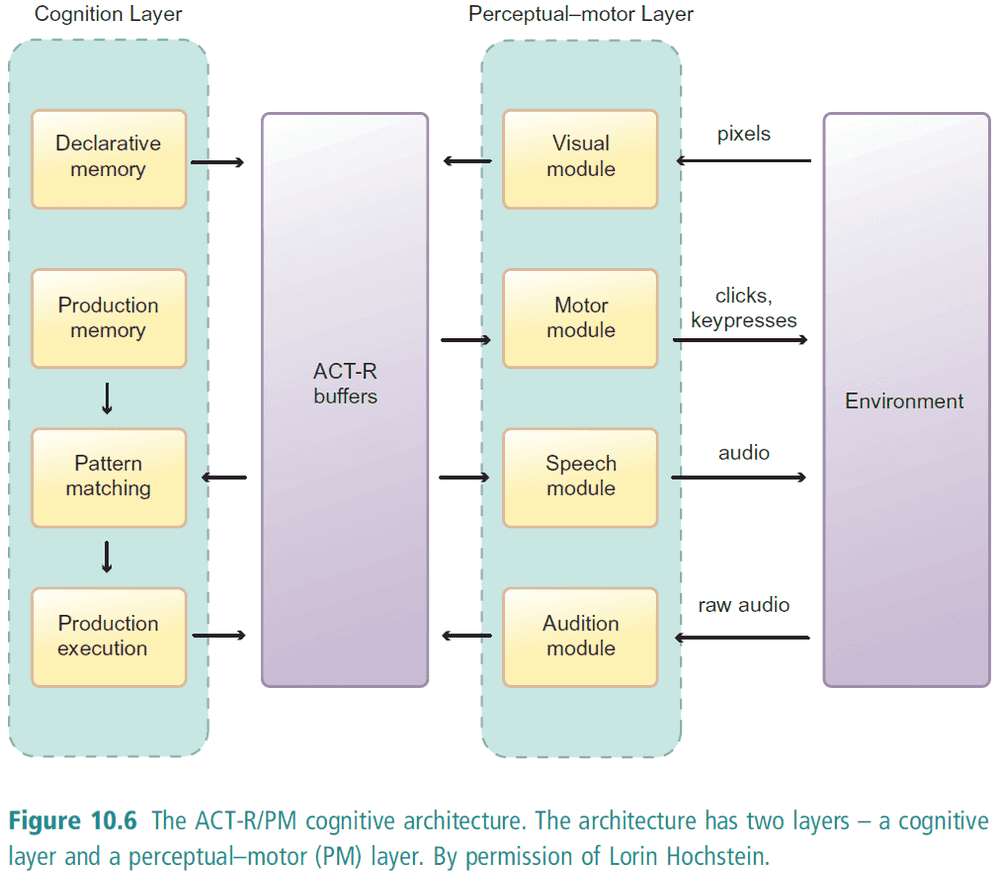

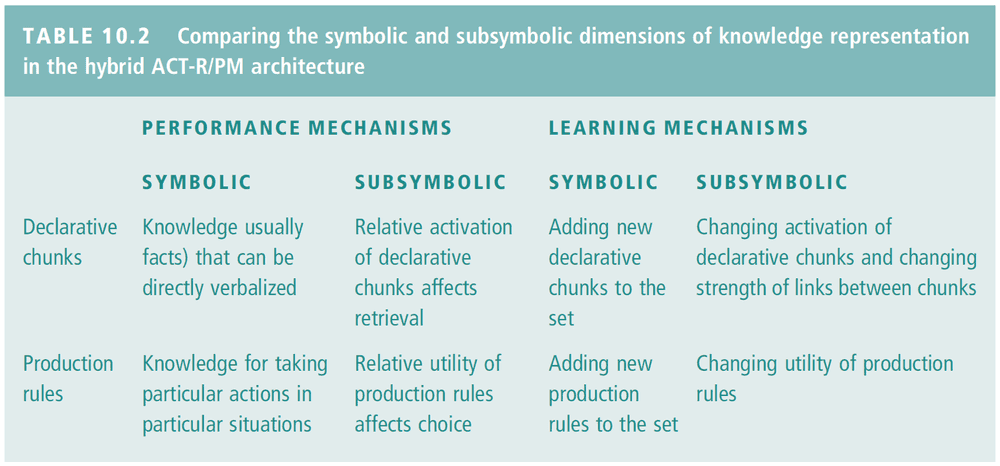

- ACT-R/PM (Adaptive Control of Thought - Rational/Perceptual Motor): a hybrid mental architecture that incorporates both symbolic and sub-symbolic information processing.

- The cognition layer is built upon the distinction between declarative (knowledge-that) and procedural (knowledge-how) knowledge.

- Both types of knowledge are represented symbolically, but in different ways.

- Declarative knowledge is stored in chunks while procedural knowledge is stored in production rules.

- Production rules (IF-THEN) can retrieve chunks from memory, modify a chunk, or call another production rule. This enables complex behaviors.

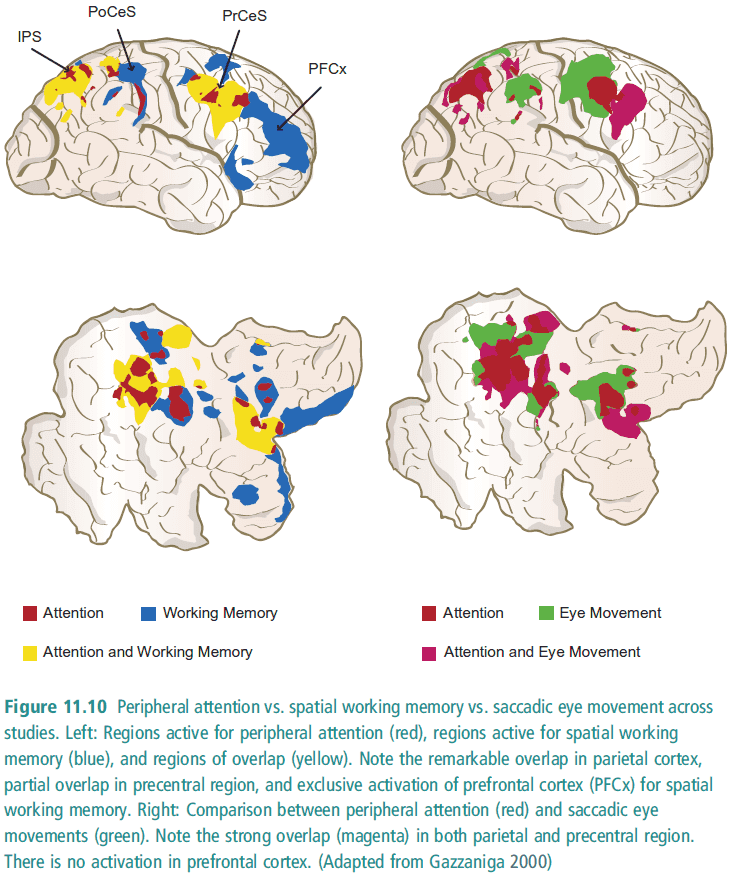

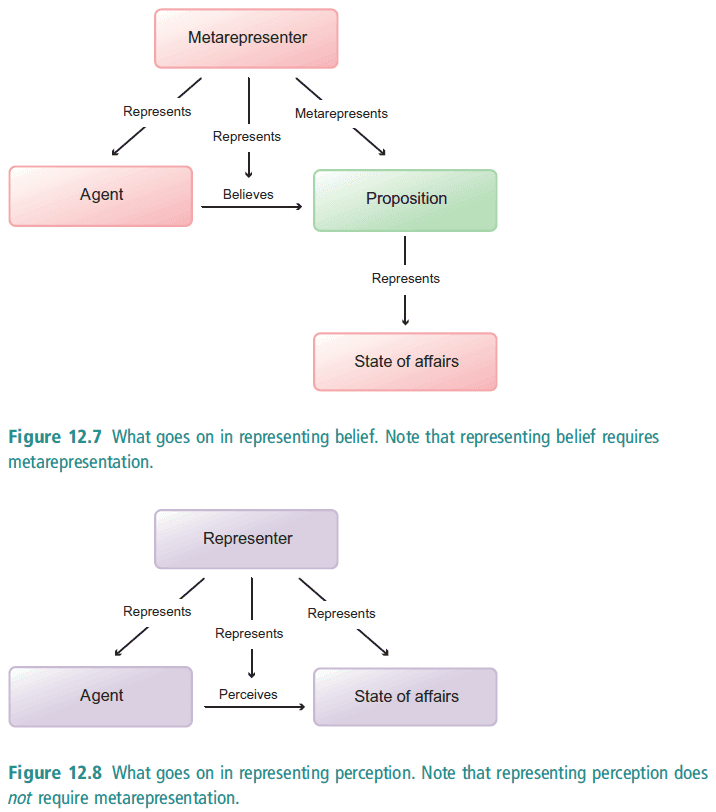

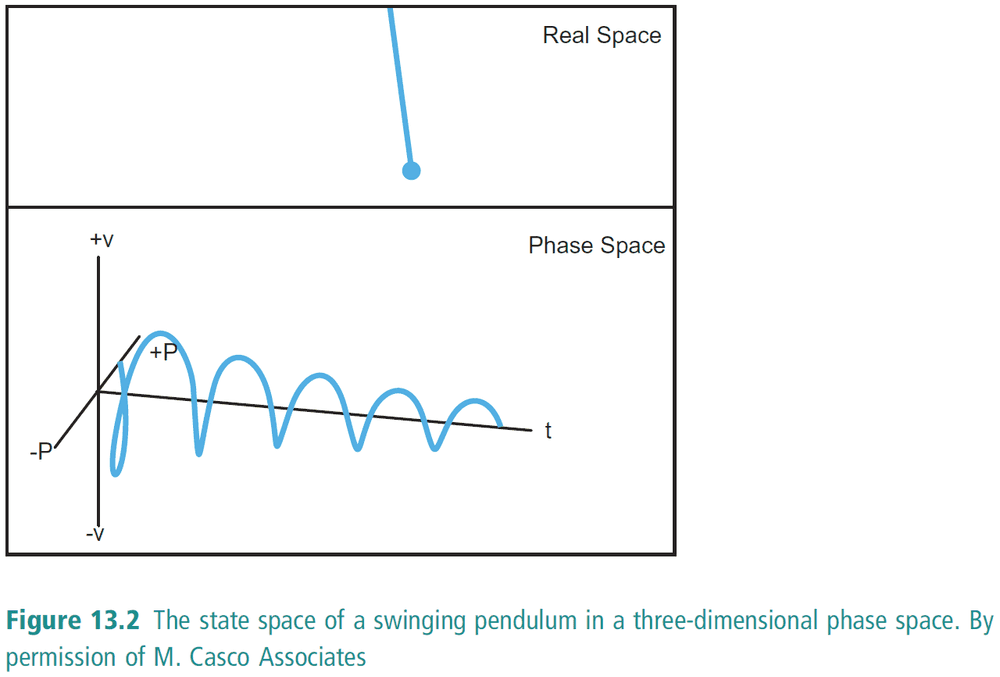

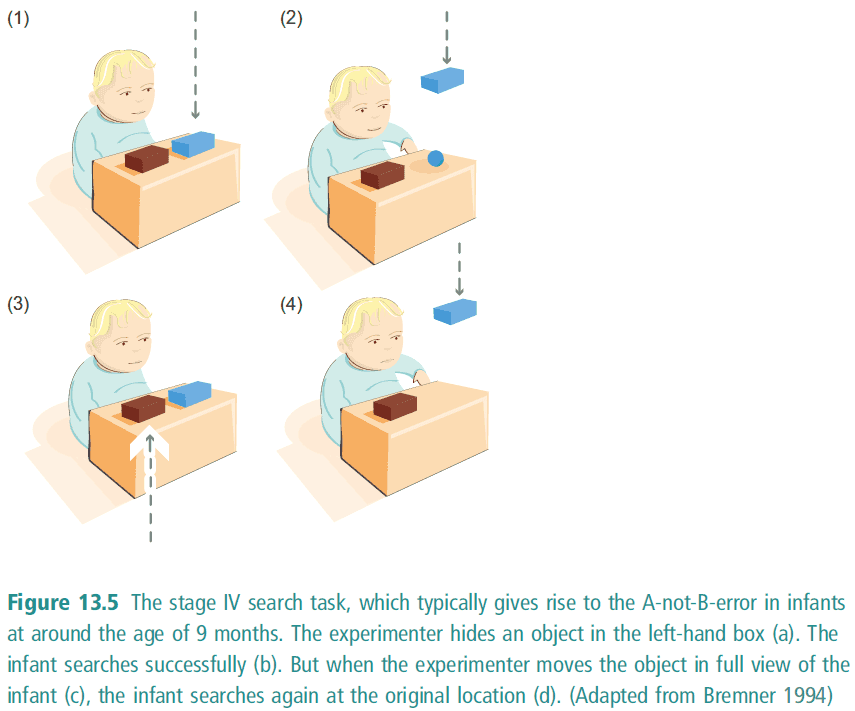

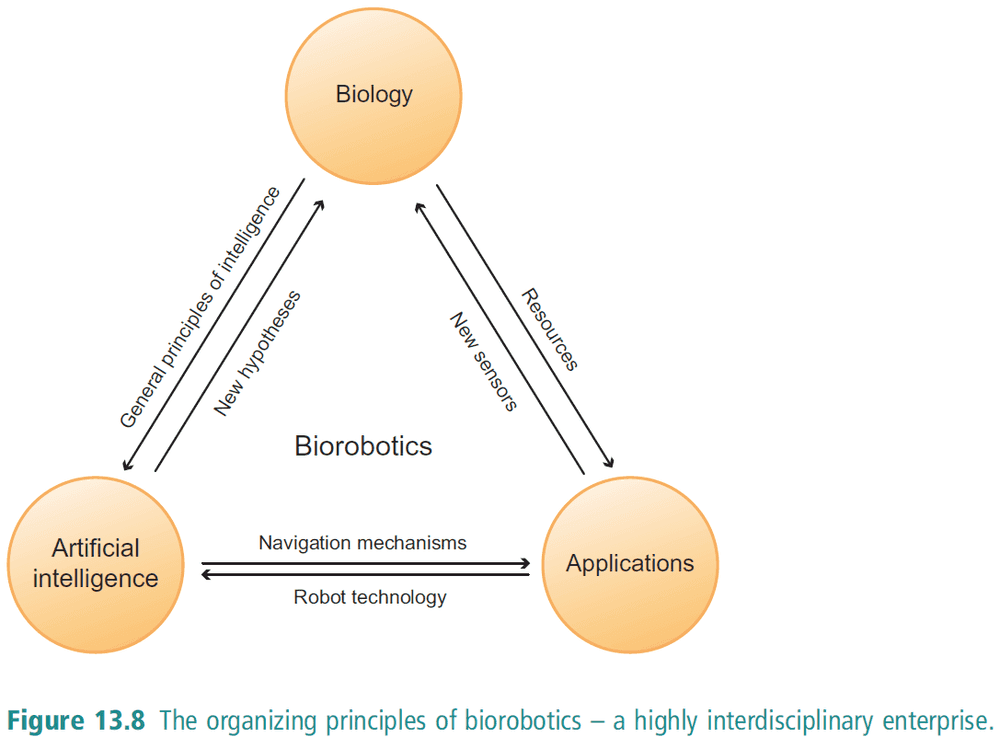

- So far, this shows how ACT-R/PM is a physical symbol system, but the hybrid part is that there isn’t any central processing nor is it massively modular.