Cognitive Neuroscience: The Biology of the Mind

By Michael S. Gazzaniga, Richard B. Ivry, George R. MangunAugust 07, 2020 ⋅ 89 min read ⋅ Textbooks

We've always defined ourselves by the ability to overcome the impossible. And we count these moments. These moments when we dare to aim higher, to break barriers, to reach for the stars, to make the unknown known. We count these moments as our proudest achievements. But we lost all that. Or perhaps we've just forgotten that we are still pioneers. And we've barely begun. And that our greatest accomplishments cannot be behind us, because our destiny lies above us.

Part I: Background and Methods

Chapter 1: A Brief History of Cognitive Neuroscience

- Big questions

- What evidence suggests that the brain’s activities produce the mind?

- What can we learn about the mind and brain from modern research methods?

- Cognition: the process of knowing.

- The brain is a product of evolution and is made up of living cells.

- Evolutionary perspective

- Why might this behavior have been selected for?

- How could it have promoted survival and reproduction?

- What would a hunter-gatherer do?

- The evolutionary perspective helps us gain insight on why the brain is the way that it is.

- Dualism: the belief that the mind appears from elsewhere and isn’t the result of the brain.

- Cognitive neuroscience disagrees with dualism and believes that the conscious mind is a product of the brain’s physical activity and isn’t separate from it.

- Evidence for this view comes from studying patients with brain lesions.

- Localizationism: the belief that certain parts of the brain are responsible for certain functions.

- Aggregate field theory: the belief that the whole brain participates in behavior.

- Aggregate field theory fell out of favor to the localizationist view.

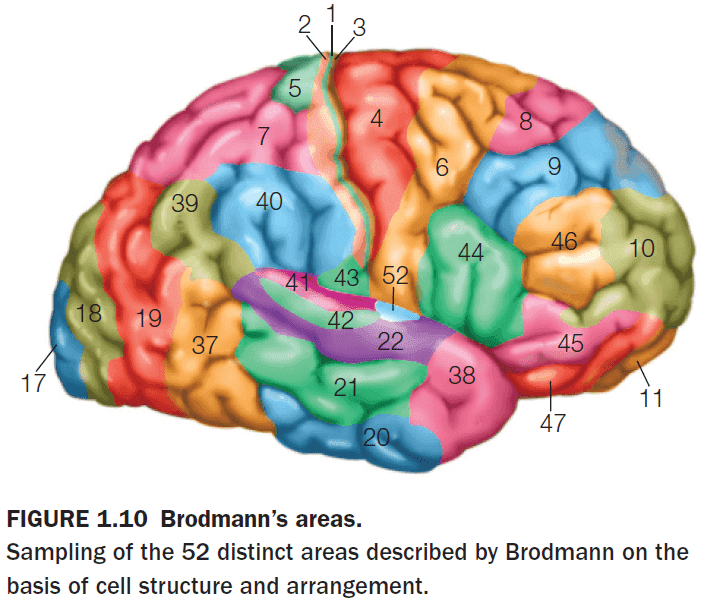

- Since different brain regions perform different functions, it follows that they ought to look different at the cellular level.

- Indeed, it’s the case that different brain areas do represent functionally distinct brain regions.

- Neuron doctrine: the concept that the nervous system is made up of individual cells called neurons.

- Neurons only transmit electrical information in one direction, from dendrites to axons.

- Knowledge of the parts must be understood together with the whole.

- Introduction to behaviorism and the cognitive revolution.

- Chomsky showed how the sequential predictability of speech follows from adherence to grammatical, not probabilistic rules.

- E.g. When children are exposed to a finite set of word orders, they can come up with a sentence and word order that they’ve never heard before. They didn’t make new sentences using associations from previous word orders.

- Associationism: that any response followed by a reward would be maintained, and that associations were the basis of how the mind learned.

- Associationism can’t explain how children learn language.

- The complexity of language was built into the brain, and it runs on rules and principles that transcend all people and all languages.

- Language is innate and is universal.

- Introduction to EEG, CT, PET, MRI, fMRI, and BOLD.

- Blood flow is directly related to brain function as evident by Seymour Kety’s experiments.

- Can we study how the mind works without studying the brain?

- In some ways, yes.

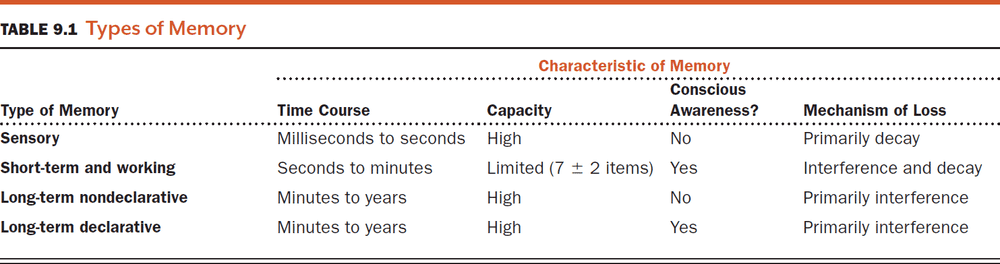

- E.g. That short-term memory can only store seven items, give or take two, in memory without invoking any neural explanation.

- However, this would be like studying computer software without understanding computer hardware. Software is implemented on hardware and is subject to hardware’s limitations.

Chapter 2: Structure and Function of the Nervous System

- Big questions

- What are the elementary building blocks of the brain?

- How is information coded and transmitted in the brain?

- What are the organizing principles of the brain?

- What does the brain’s structure tell us about its function and the behavior it supports?

- The goal of cognitive neuroscience is to understand how the 89 billion neurons of the human brain enable us to

- Walk

- Talk

- Imagine the unimaginable

- Since all theories of how the brain enables the mind must mesh with the actual nuts and bolts of the nervous system, we start with the nuts and bolts: neurons.

- The nervous system is made up of two main classes of cells

- Neurons

- Glial

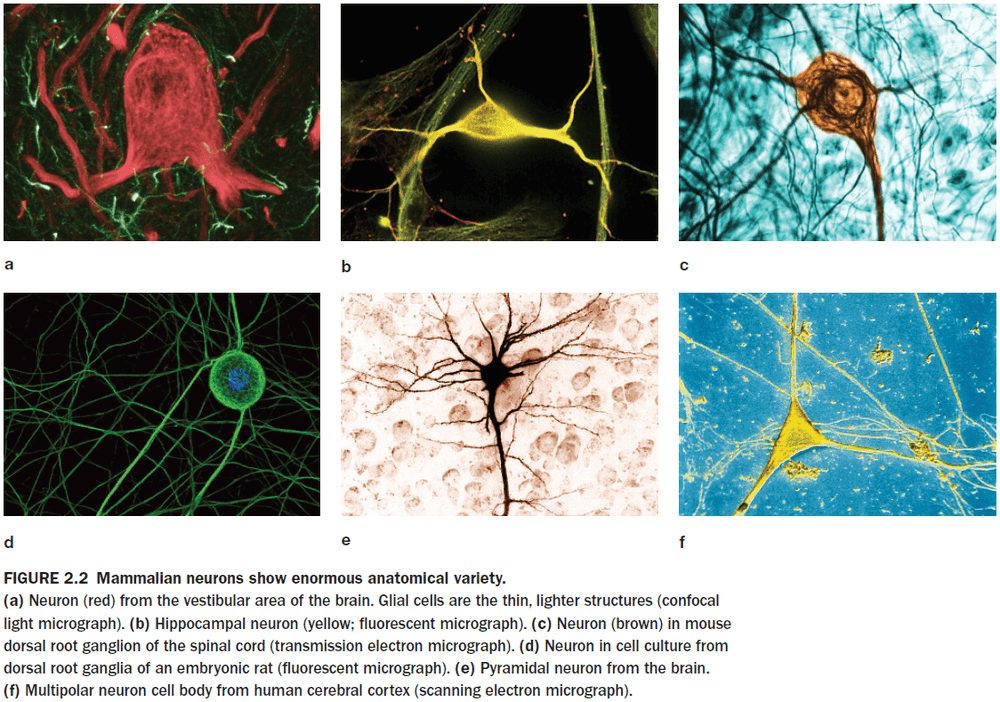

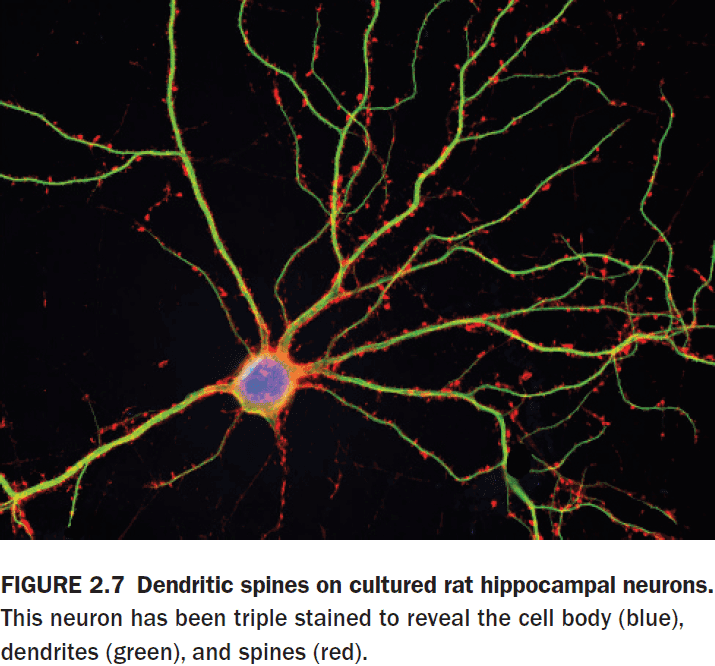

- Neuron: the basic signalling unit that transmits information throughout the nervous system.

- Neurons take in information, make a decision about it following some simple rules, and then passes on the signal to other neurons or muscles.

- Neurons vary in their form, location, and interconnectivity and these variations are closely related to their function.

- Glial cells provide structural support, electrical insulation, and modulate neuronal activity.

- Introduction to astrocytes, blood-brain barrier, myelin, and neurons.

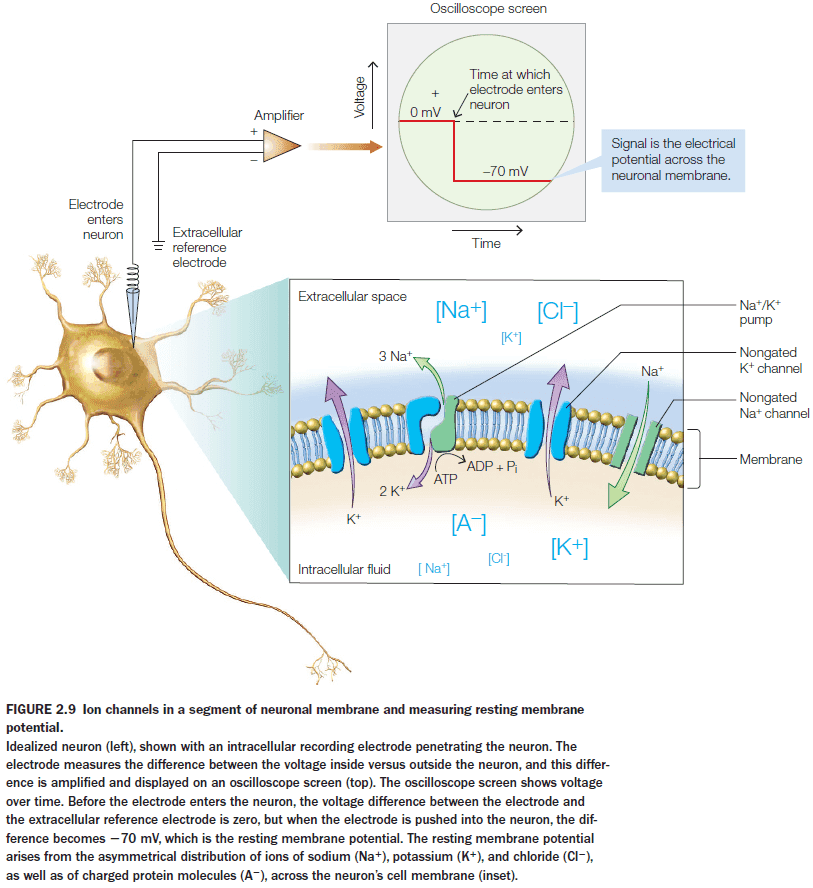

- The main ions for neurons are: potassium, sodium, chloride, and calcium.

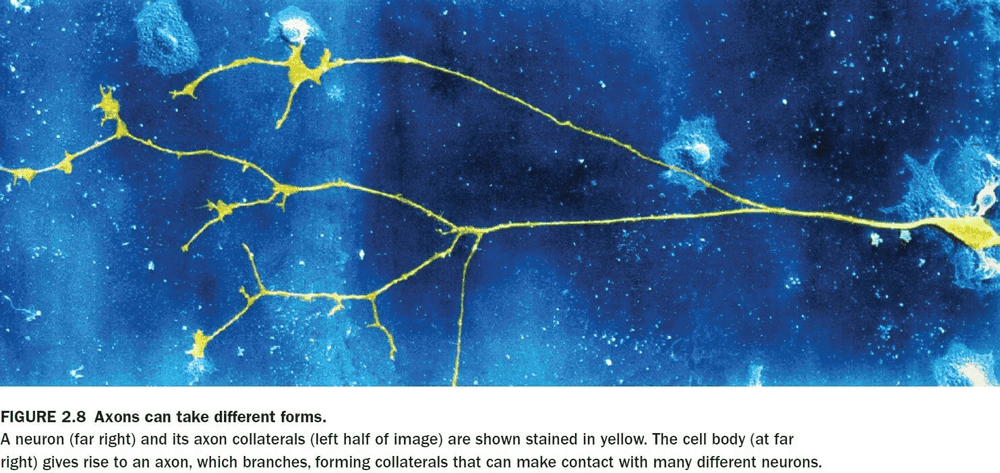

- Some axons branch to form axon collaterals that can transmit signals to more than one cell.

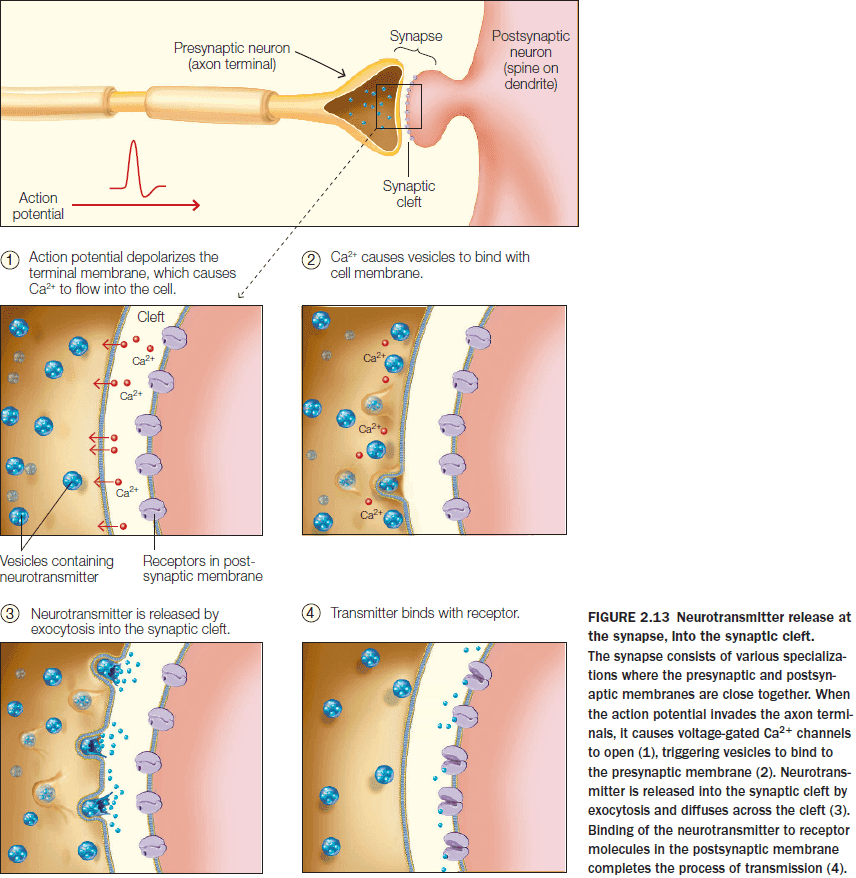

- Introduction to chemical and electrical synapses, presynaptic and postsynaptic label, resting membrane potential, and ion channels and pumps.

- The neuronal membrane is more permeable to potassium ions than sodium ions because there are more potassium channels than any other type of ion channel.

- Unlike most cells in the body, neurons are excitable meaning that their membrane permeability can change.

- Membrane permeability can change because membranes have ion channels that can change their permeability for a particular ion.

- The small electrical current produced by an EPSP is passively conducted through the cytoplasm of the dendrite, cell body, and axon.

- Passive current conduction diminishes with distance due to leakage and has a maximum travel distance of about 1 mm.

- This is a problem for signals traveling over long distances such as from the brain to your toes.

- So how does the neuron solve this problem of diminishing current over long distances?

- Neurons evolved a clever mechanism to regenerate and pass along the signal received at synapses on the dendrite. The mechanism is the action potential.

- Action potential (AP): a rapid depolarization and repolarization of a small region of the membrane caused by the opening and closing of ion channels.

- APs enable signals to travel for meters with no loss in signal strength because they’re continually regenerated at each patch of membrane on the axon.

- APs are able to regenerate themselves because of voltage-gated ion channels.

- Since APs always have the same amplitude, they’re said to be all-or-none phenomena.

- The strength of an AP doesn’t communicate anything about the strength of the stimulus that initiated it.

- The intensity of a stimulus is communicated by the rate of firing of APs.

- E.g. More pressure on a patch of skin is communicated by faster AP firing.

- The effect of a neurotransmitter on the postsynaptic neuron is determined by the postsynaptic receptor’s properties rather than by the transmitter itself.

- Synapses are the locations where one neuron can transfer information to another neuron or a specialized nonneuronal cell.

- Synapses are also sites of information processing.

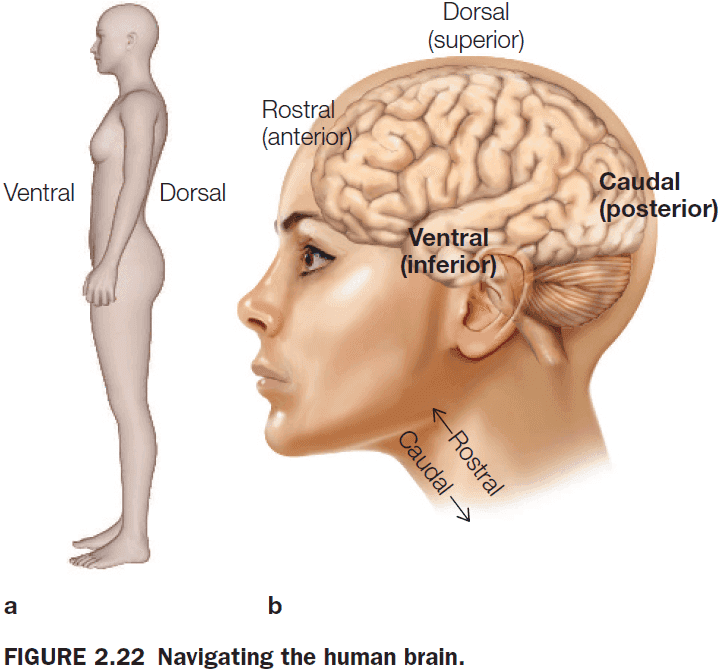

- Introduction to CNS, PNS, somatic and autonomic motor system, sympathetic and parasympathetic branches of the autonomic system, CSF, and spinal cord.

- The primary purpose of increased blood flow isn’t to increase the delivery of oxygen and glucose to the brain, but rather to quicken the removal of metabolic by-products from the increased neuronal activity.

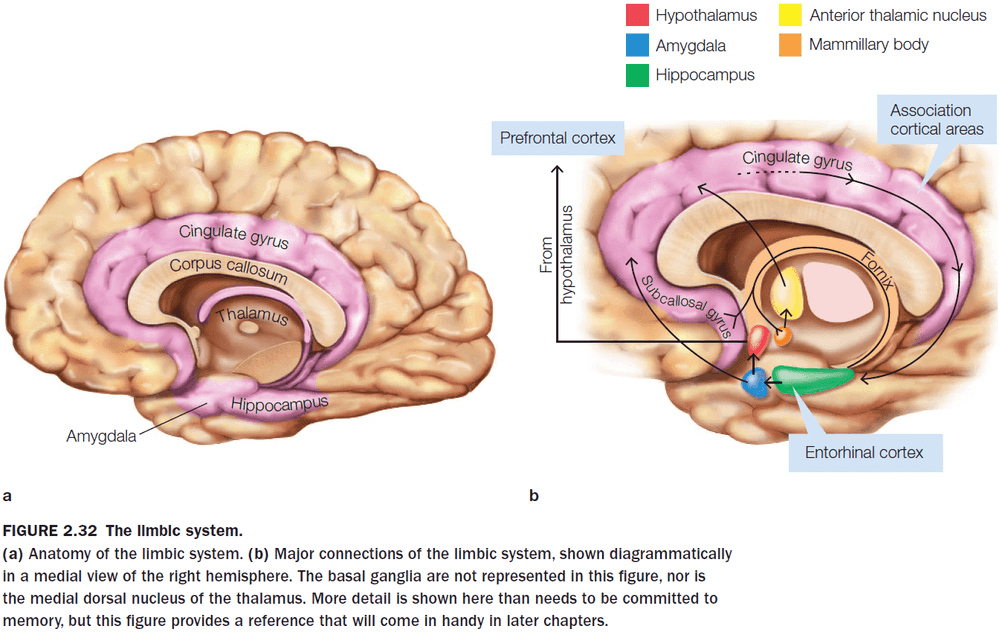

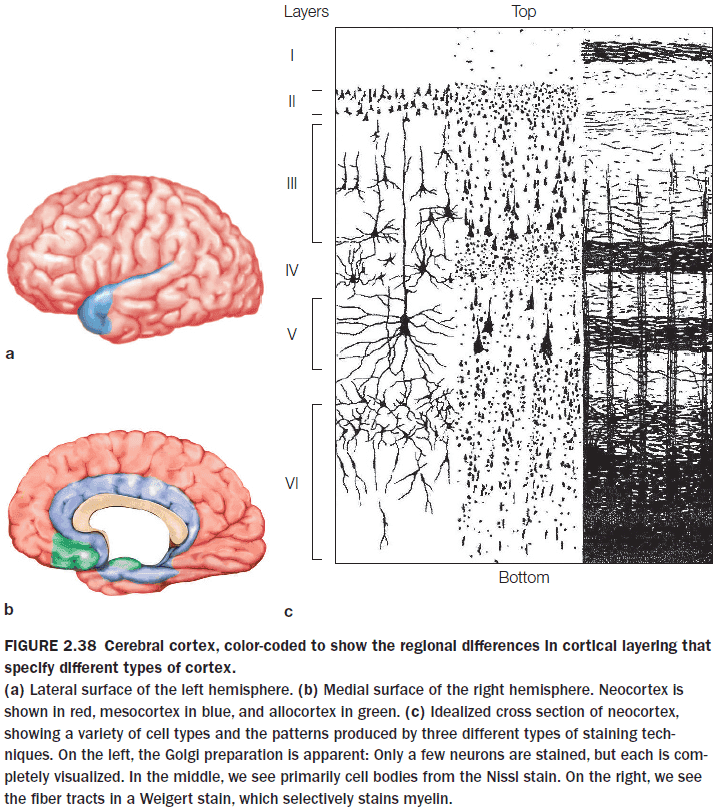

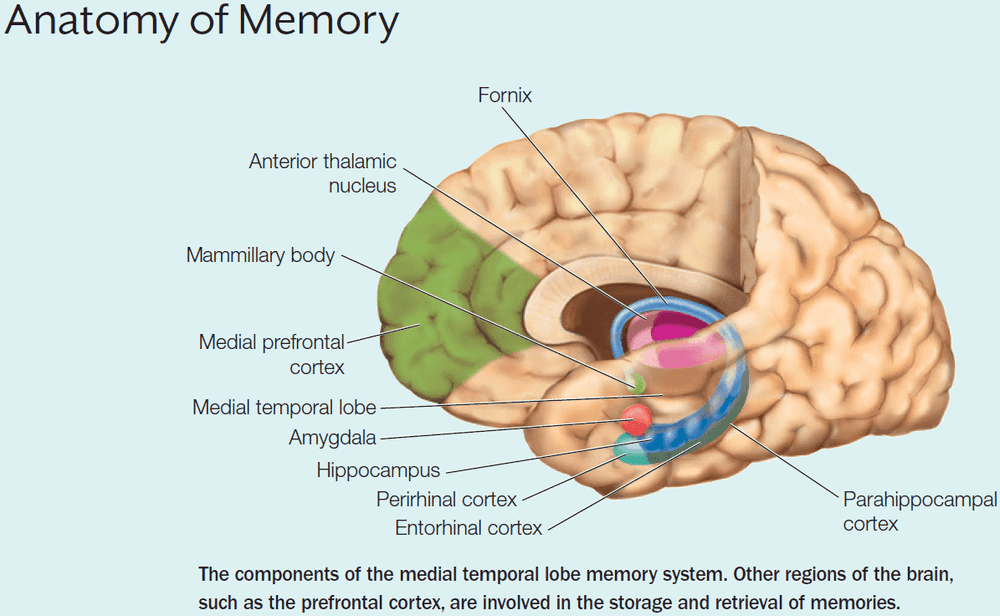

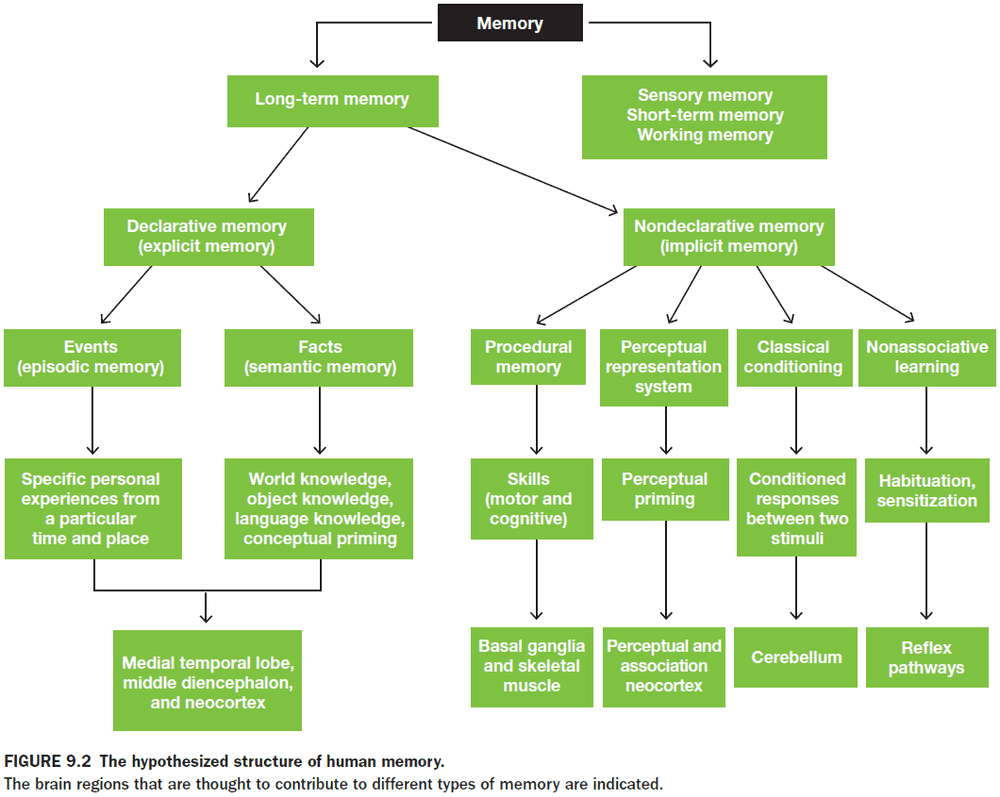

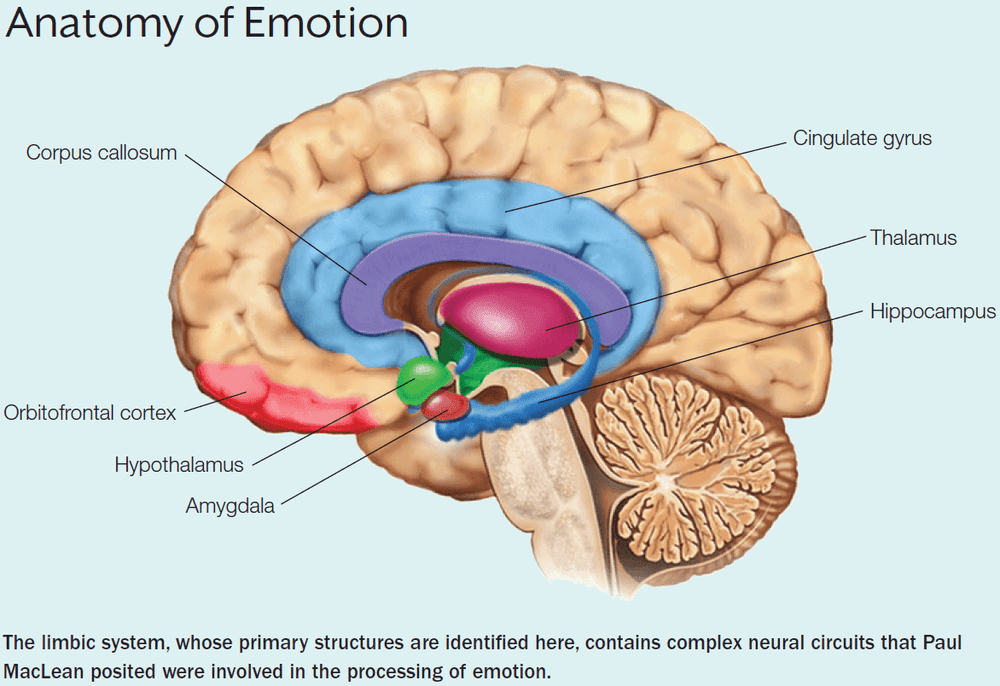

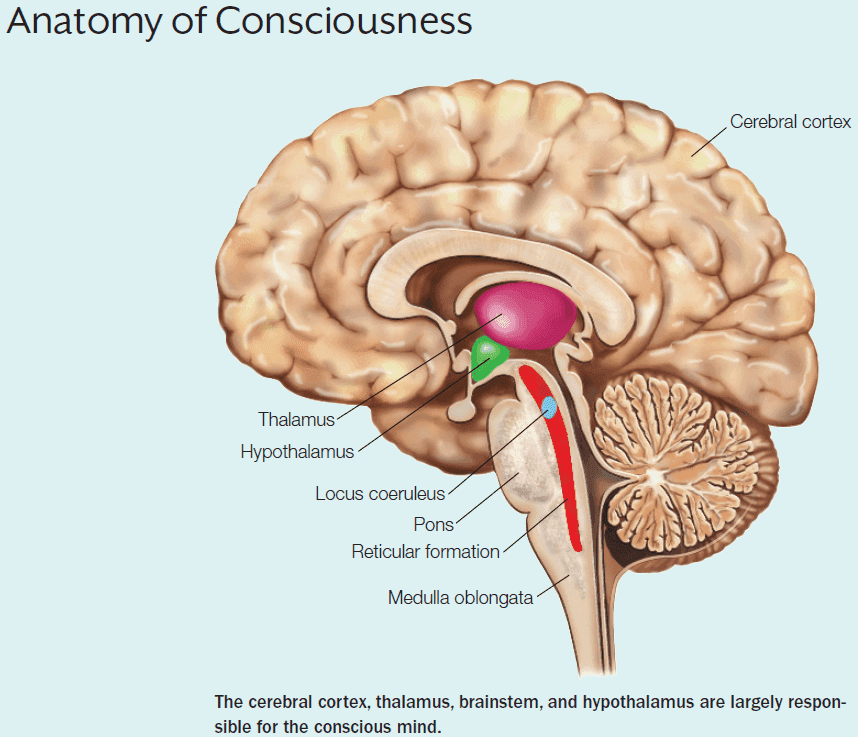

- Introduction to the brainstem, thalamus and hypothalamus, cerebrum, and cerebral cortex.

- The cerebral cortex has a total surface area of about 2200 to 2400 but because of the extensive folding, about two thirds of it is folded into the depths of the sulci.

- Unfortunately, the nomenclature of the cortex isn’t fully standardized. A region may be referred to by its Brodmann name, a cytoarchitectonic name, a gross anatomical name, or a functional name.

- E.g. Primary visual cortex = Brodmann area 17 = striate cortex = calcarine cortex = V1.

- The cortex has generally been subdivided into five principle functional subtypes

- Primary sensory areas

- Primary motor areas

- Unimodal association areas

- Multimodal association areas

- Paralimbic and limbic areas

- Somatotopy: the mapping of specific parts of the body to specific areas of the somatosensory cortex.

- Somatotopic maps aren’t set in stone and don’t have distinct borders.

- Topographic maps are a common feature of the nervous system and the area dedicated to a body part isn’t representative of the actual body part’s size.

- The area’s size is more representative of the body part’s sensitivity/usefulness.

- Visual association cortex can be activated during mental imagery when we call up a visual memory, even in the absence of visual stimulation.

- Multimodal association cortex contains cells that may be activated by more than one sensory modality.

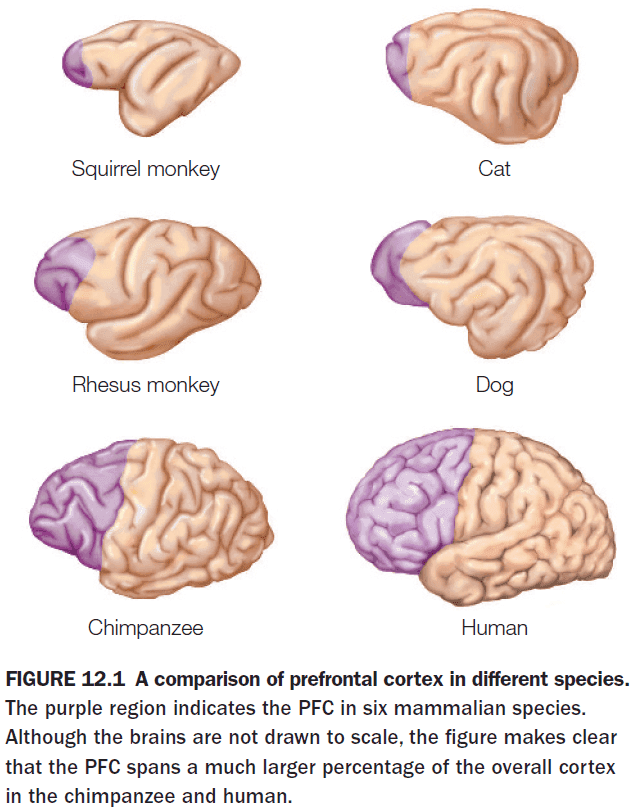

- As brains increases in size, long-distance connectivity decreases.

- The number of neurons that an average neuron connects to doesn’t change with increasing brain size. The absolute number of connections per neuron is the same.

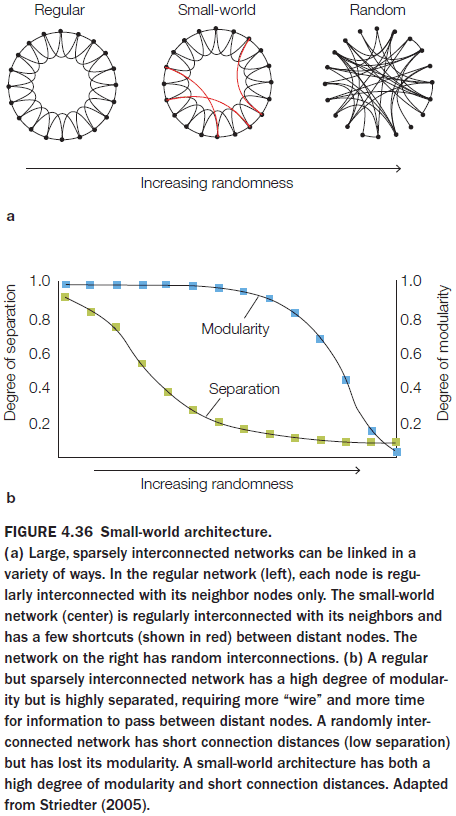

- So to decrease long-distance connectivity while maintaining an absolute number of connections, human brains have developed a small-world architecture.

- Small-world architecture: a structure that combines many short, fast local connections with a few long-distance connections to communicate the results of local processing.

- As primate brains increased in size, their overall connectivity patterns changed, resulting in anatomical and functional changes.

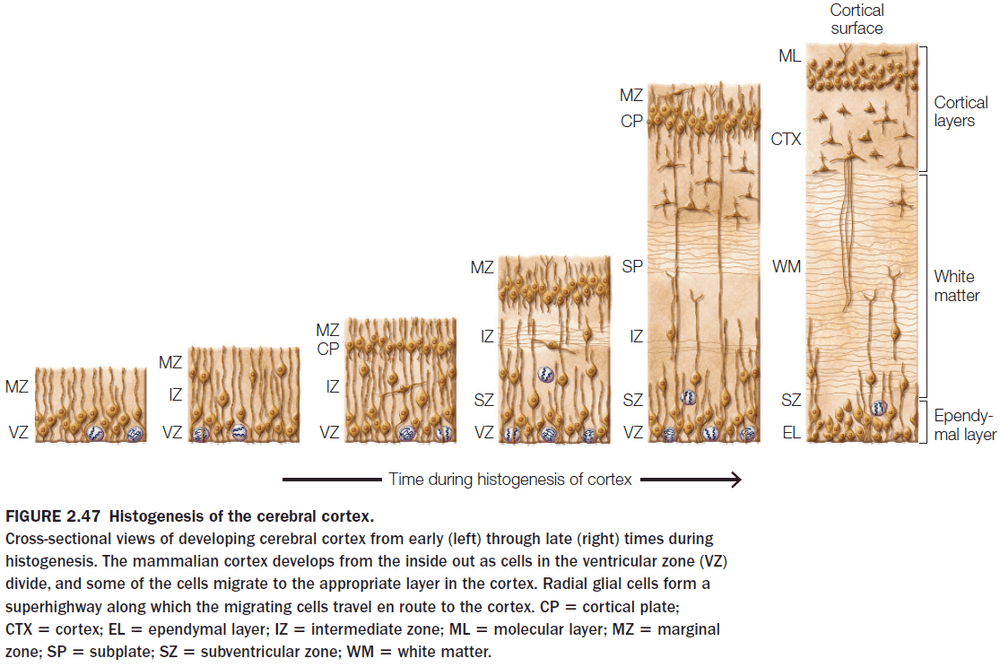

- Very few neurons are generated after birth in primates as most of the neurons are generated prenatally during the middle third of gestation.

- The cortex is built from the inside out.

- Neurogenesis: the creation of neurons.

- What determines the type of neuron that a migrating cell becomes?

- The timing of neurogenesis or when a neuron is created.

- E.g. Fetal alcohol syndrome disrupts neuronal migration resulting in a disorder cortex, leading to cognitive, emotional, and physical disabilities.

- Although the brain nearly quadruples in size from birth to adulthood, the number of neurons doesn’t increase.

- What does increase is the number of synapses, the growth of dendritic trees, and both the myelination and proliferation of glial cells.

- Synaptogenesis: the creation of synapses.

- Synaptogenesis is followed by synapse pruning, which continues for more than a decade.

- E.g. Initially, in the primary visual cortex, there’s an overlap between the projections of the two eyes onto neurons. After synaptic pruning, the cortical inputs from the two eyes are nearly completely segregated forming ocular dominance columns.

- There’s also compelling evidence suggesting that different brain regions reach maturity at different times.

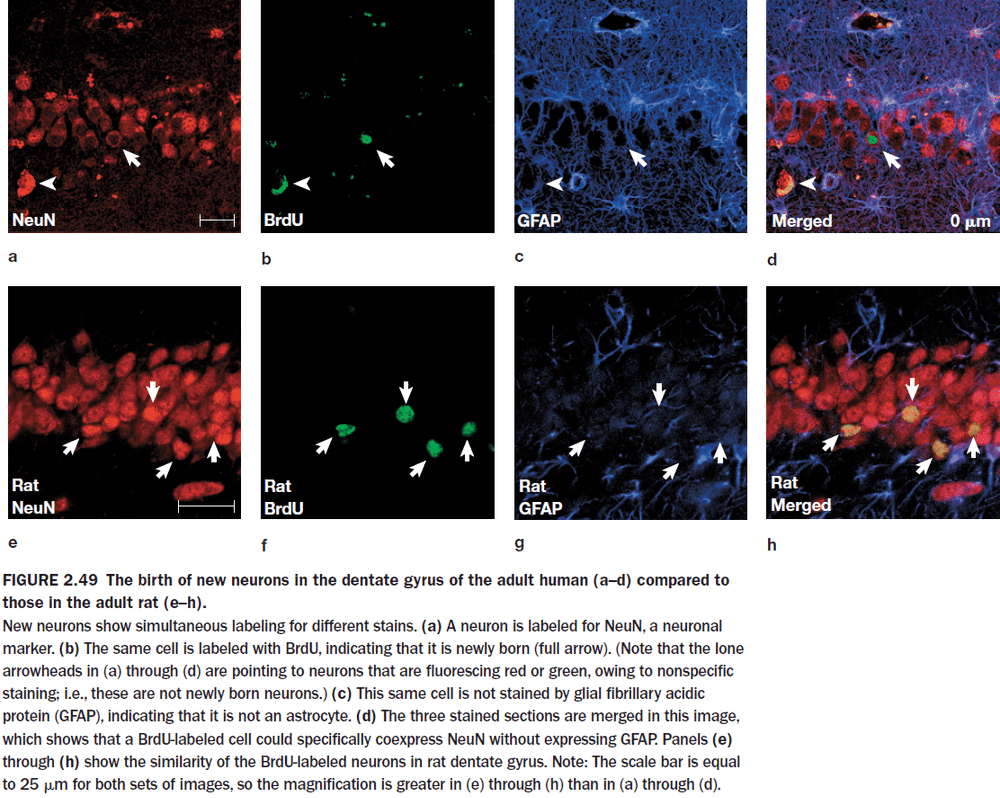

- Neurogenesis was once thought to have not occurred in the adult human brain but this isn’t true.

- Neurogenesis in adult humans has now been well established in the hippocampus and the olfactory bulb, but we are unsure if it occurs elsewhere in the human brain.

- Evidence of this comes from terminally ill cancer patients who took a substance that marks cell division. The substance was used to track the division of cancer cells but it’s also useful in tracking the division of new neurons.

- The marker showed up in the subventricular zone of the caudate nucleus and in the granular cell layer of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus.

Chapter 3: Methods of Cognitive Neuroscience

- Big questions

- Why is cognitive neuroscience an interdisciplinary field?

- The most fundamental tool for all scientists: the scientific method.

- Steps of the scientific method

- Observation

- Hypothesis

- Prediction

- Experiment

- Repeat

- There’s an asymmetry in the scientific method as results from an experiment can only prove that a hypothesis is false, not that a hypothesis is true.

- This is also known as falsifiability or the ability to be proven false.

- Cognitive psychology: the study of mental activity as a information-processing problem.

- A basic assumption in cognitive psychology is that we don’t directly perceive and act in the world, but rather our perceptions, thoughts, and actions depend on the internal representations obtained by our sense organs.

- Cognitive psychology is also trying to uncover the secrets of how information is processed in the brain.

- E.g. It’s surprisingly easy to read the right-side passage.

| Randomize all letters | Randomize all letter except the first and last letter |

|---|---|

| ocacdrngi ot a sehrerearc ta macbriegd ineyurvtis, ti edost’n rtt aem ni awth rreod eht tlteser ni a rwdorea, eht ylon pirmtoatn gihtn si att h het rift s nda satltt elre eb ta het ghitr clepa. eht srte anc eb a otltasesm dan ouy anc itlls arde ti owtuthi moprbel. ihstsi cebusea eth nuamh nidm sedo otn arde yrvee telrte yb stifl e, tub eth rdow sa a lohew. | Aoccdrnig to a rseheearcr at Cmabrigde Uinervtisy,it deosn’t mttaer in waht oredr the ltteers in a wrodare, the olny iprmoatnt tihng is taht the frist and lsatltteer be at the rghit pclae. The rset can be a totalmses and you can sitll raed it wouthit porbelm. Tihsis bcuseae the huamn mnid deos not raed ervey lteterby istlef, but the wrod as a wlohe. |

- As long as the first and last letters of each word are in the correct position, we can accurately infer the word given the context.

- Two key concepts of cognition

- Information processing depends on mental representations.

- Mental representations undergo internal transformations.

- Context helps choose which representational format is most useful.

- E.g. To show a ball rolling down a hill, it’s more useful to show a visual/pictorial representation than a physics/math representation.

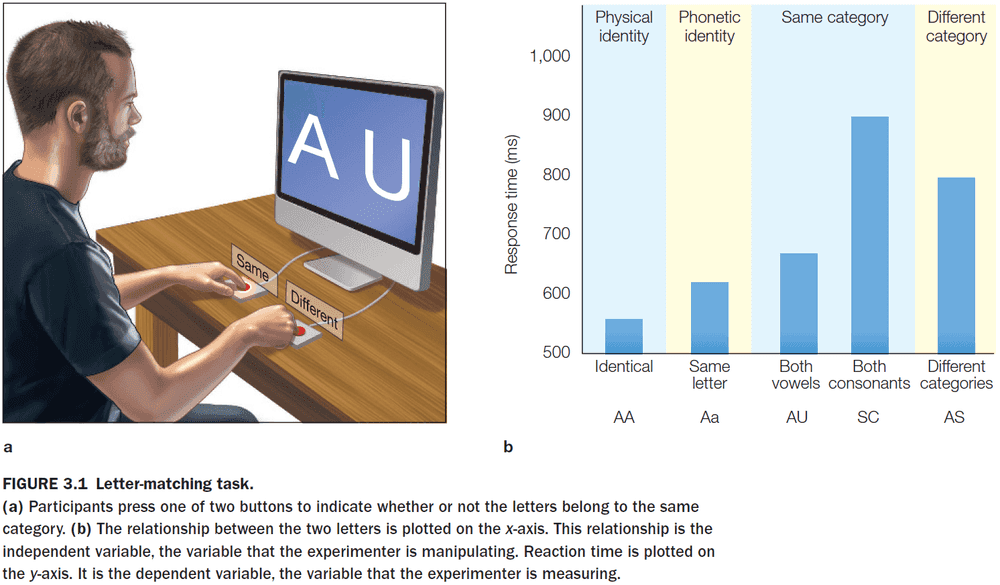

- The letter-matching task shows that the mind creates multiple representations of the same (and in this case, simple) stimuli.

- A letter can be represented physically, phonetically, and categorically (either a vowel or consonant).

- The different response latencies reflect the degrees of processing required to perform the letter-matching task.

- By using this logic, we infer that physical representations are activated first, phonetic representations next, and category representations last.

- Transforming internal representations depends on your

- Memory

- Attention

- E.g. The smell of pizza might remind one person of Italy while it reminds another person of NYC. Processing the internal representation of “pizza” differs in each person due to their memory.

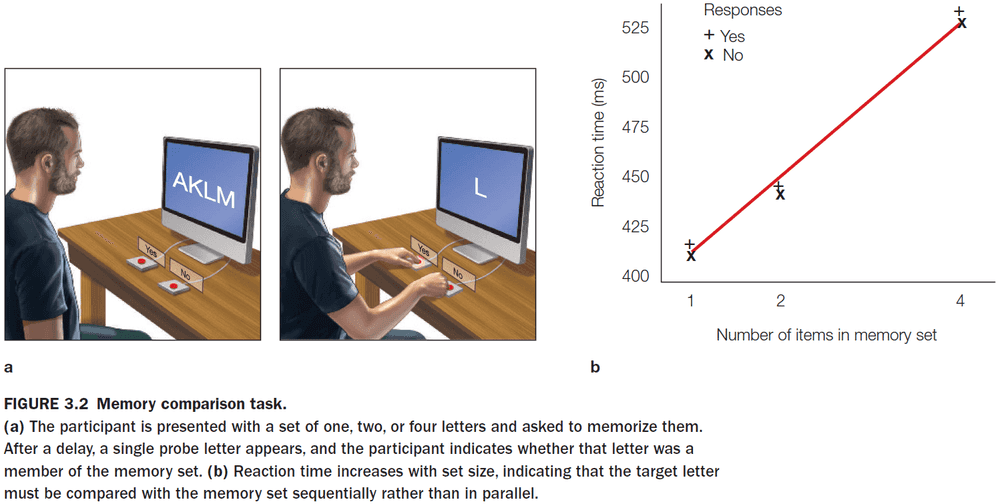

- The memory comparison task shows that the comparison process in recognition memory is serial. Recognizing an item in a larger memory set requires more time.

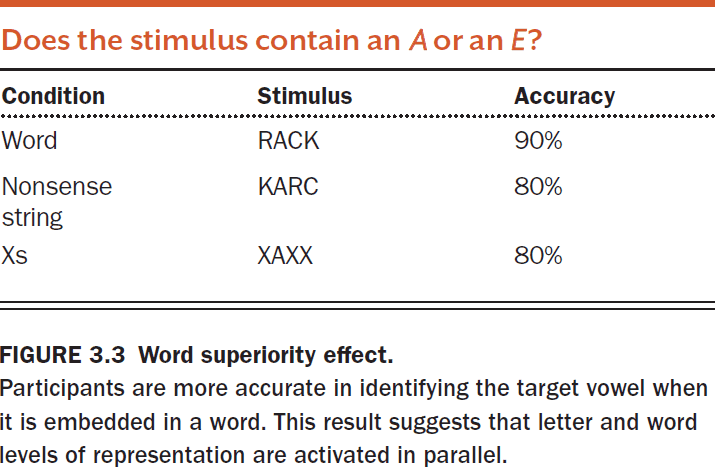

- While this task shows that memory recognition is serial, the word superiority effect shows that the mind also has parallel processes.

- The word superiority effect shows that we have parallel processes because we activate both representations of each letter and of the entire word in parallel.

- This parallel processing enables us to perform better on the task because both representations can provide information as to whether the target letter is present.

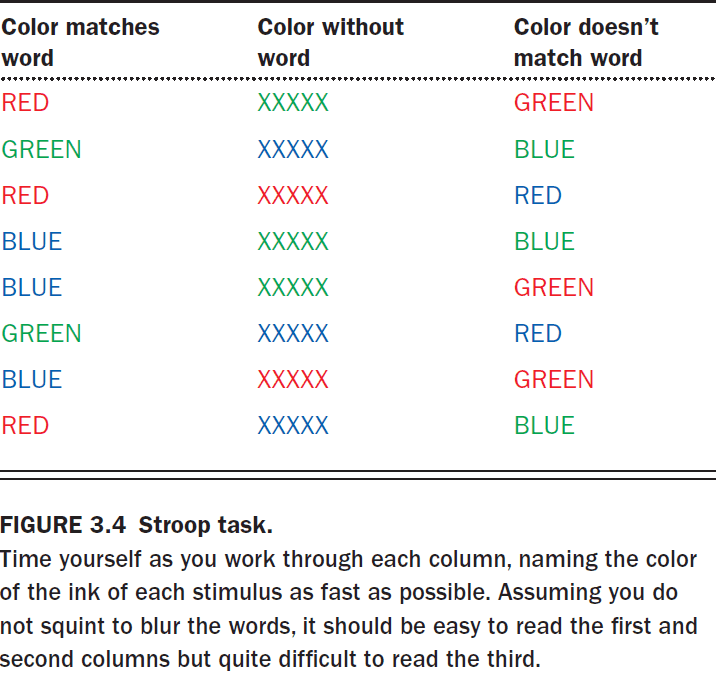

- Another piece of evidence of parallel processing is the Stroop task.

- The mind activates multiple representations for each word

- Word representation

- Color representation

- When the representations don’t match, it’s more difficult to read the words as evident by the increased time to finish reading the list.

- Another way to uncover information about the brain and mind is through studying the damaged brain.

- Ways the brain can be damaged

- Vascular/blood disorders

- Tumors

- Degenerative and infectious disorders

- Traumatic Brain Injury

- Epilepsy

- The brain uses 20% of the oxygen we breathe but only accounts for 2% of our total body mass.

- The vascular system is fairly consistent between individuals, thus a stroke of a particular artery typically leads to destruction of tissue in a consistent anatomical location.

- For brain tumors, the first concern is its location, not whether it’s benign or malignant, because the tumor may be close to critical brain structures such as the brain stem.

- Single dissociation: damage to one brain area affects one task but not another.

- E.g. Damage to Broca’s area affects speech but not comprehension.

- Double dissociation: damage to area X impairs the ability to do task A but not task B, and damage to area Y impairs the ability to do task B but not task A.

- Double dissociations show that two areas have complementary processing.

- E.g. Damage to Broca’s area affects speech and damage to Wernicke’s area affects comprehension.

- Double dissociations offer the strongest neuropsychological evidence that a brain area is responsible for a specific task.

- Associating neural structures with specific processing operations calls for appropriate control conditions.

- E.g. Comparing healthy people to patients with brain damage.

- We must also be weary that missing parts may not be directly causing a function/task.

- E.g. Cutting the spark plug wires and cutting the gas line both stop a car from running, but this doesn’t mean they have the same function.

- Lesion may also result in the development of compensatory processes.

- E.g. Depriving monkeys of sensory feedback in one arm causes them to stop using that arm. However, if the other arm is also deprived, the monkey goes back to using both.

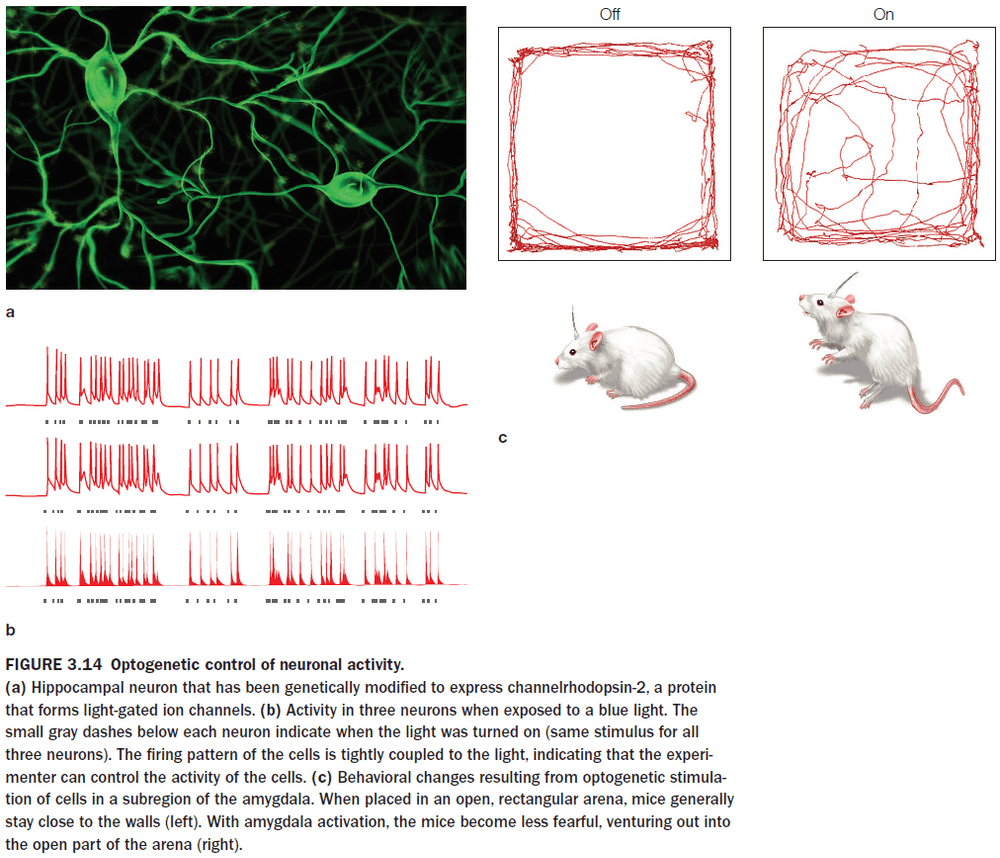

- Methods to perturb neural function

- Pharmacology

- Genetic manipulations

- Invasive stimulation (electrical)

- Noninvasive stimulation (magnetic)

- These methods can be tested in both “on” and “off” states, enabling within-participant comparisons of performance.

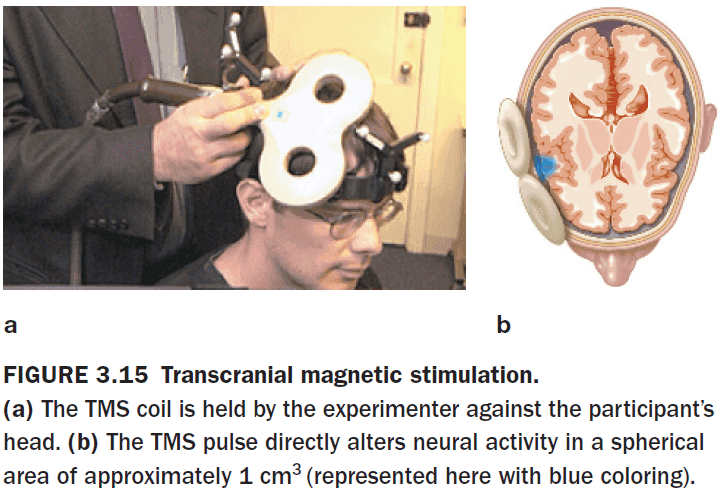

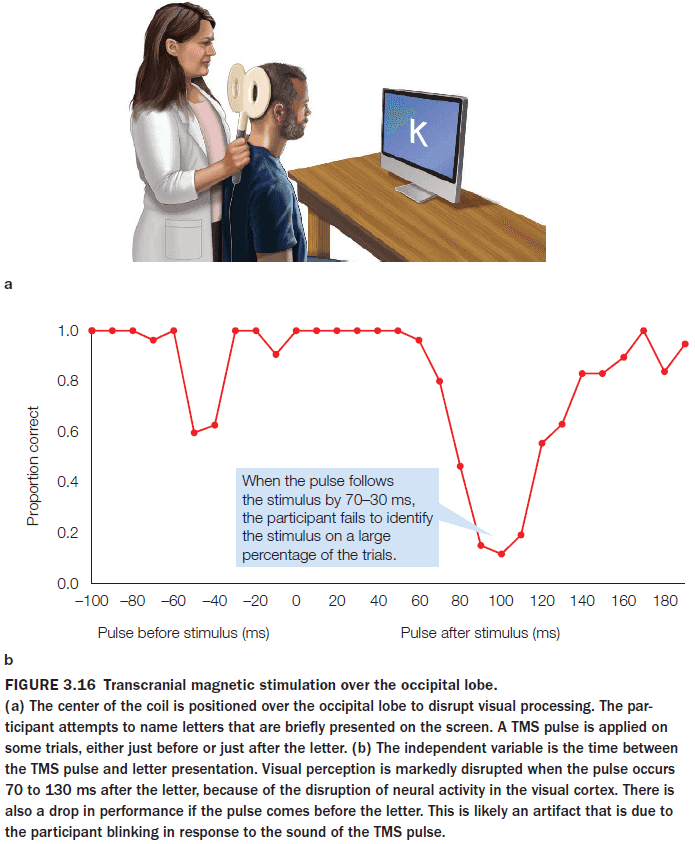

- When transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is applied at a low frequency (1 Hz) over 10-15 minutes, cortical excitability decreases.

- When TMS is applied at higher frequencies (10 Hz), cortical excitability increases.

- Interestingly, when TMS is applied at very high frequencies (15 Hz), cortical activity is depressed in the targeted region for 45 to 60 minutes.

- When using TMS, participants are usually not aware of any stimulation effects.

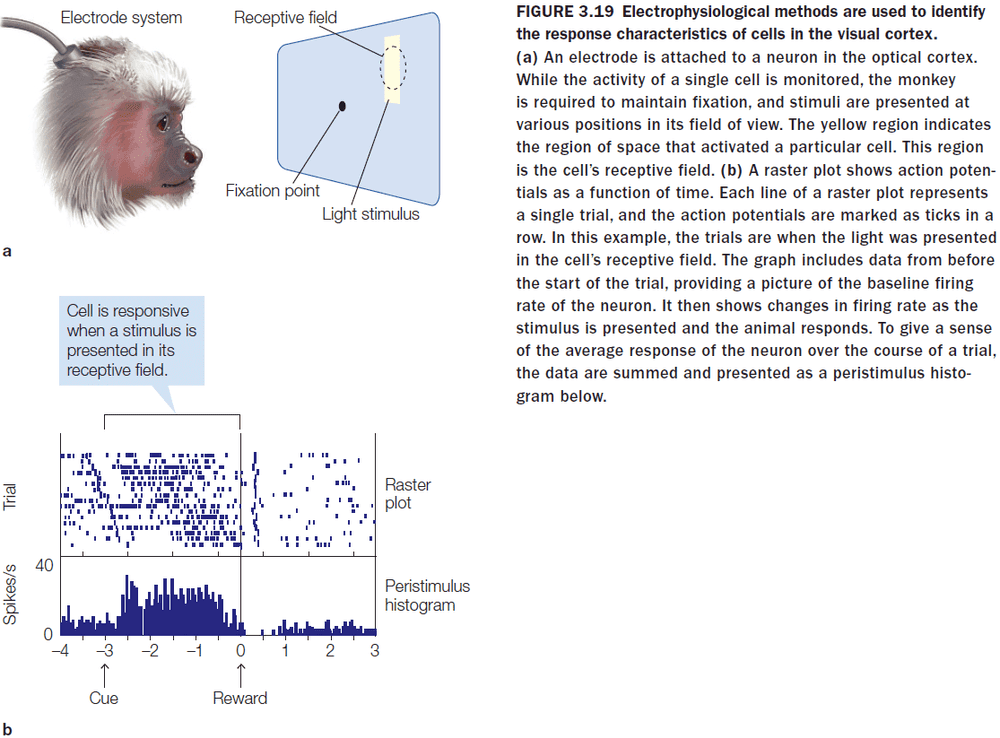

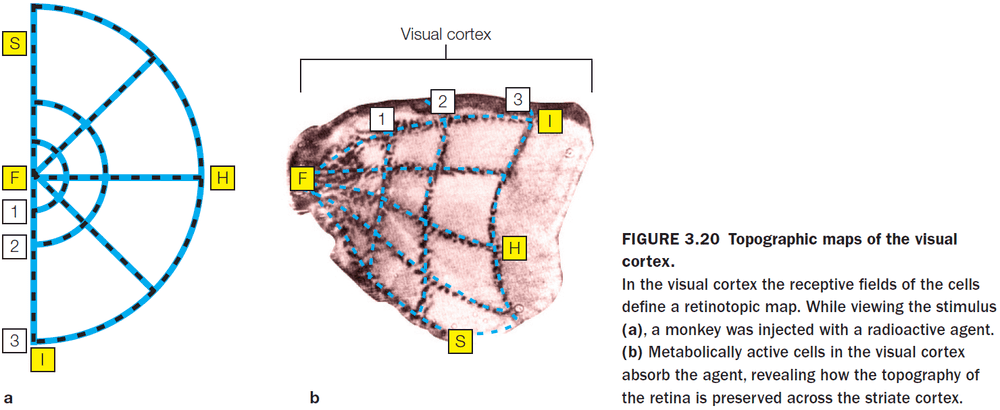

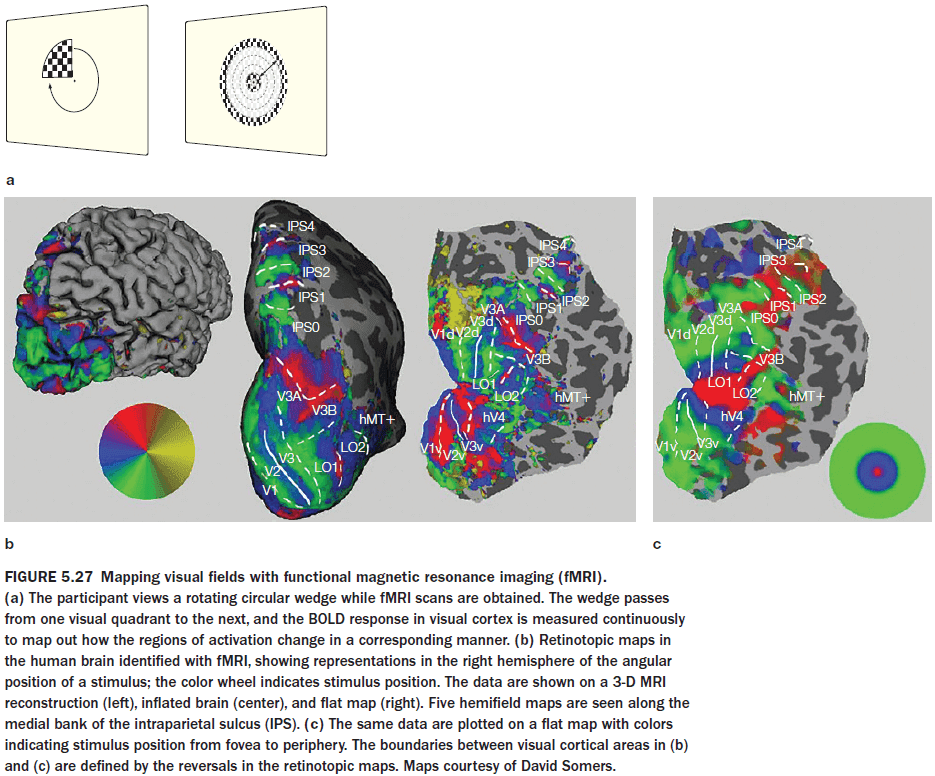

- Review of CT, MRI, DTI, single-cell recording, receptive fields, and topographic representations.

- Cell activity within a retinotopic map correlates with the location of the stimulus.

- Electrocorticography (ECoG): an invasive EEG performed directly on the surface of the brain.

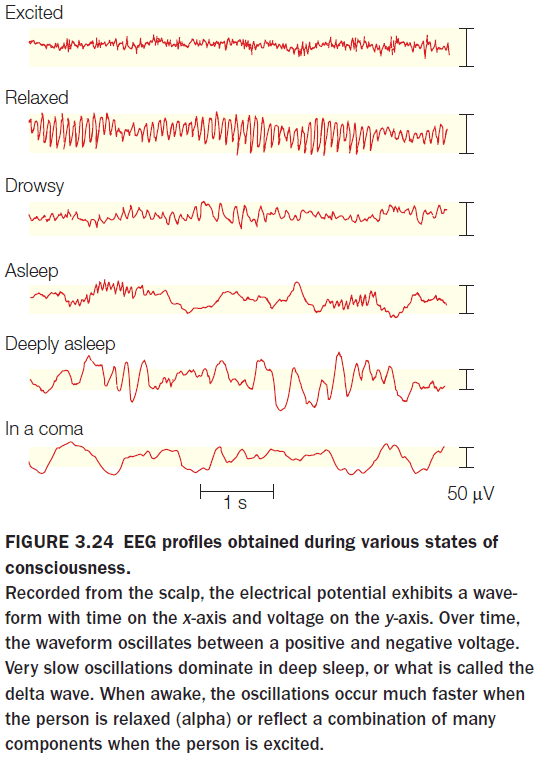

- Frequency bands for EEG and ECoG

- Delta (1-4 Hz)

- Theta (4-8 Hz)

- Alpha (7.5-12.5 Hz)

- Beta (13-30 Hz)

- Gamma (30-70 Hz)

- High Gamma (> 70 Hz)

- Many years of research have shown that the power in these bands is an excellent indicator of the state of the brain.

- E.g. An increase in alpha power is associated with reduced states of attention and an increase in theta power is associated with engagement in a cognitively demanding task.

- Event-related potential (ERP): a tiny signal embedded in an EEG signal that’s triggered by a stimulus/movement.

- The amount of blood supplied to the brain varies only a bit when the brain is most active compared to when it’s resting.

- Since the input of resources remains roughly constant, the brain must distribute it’s resources differently depending on the need.

- When a brain area is more active, increasing the blood flow to that region provides it with more oxygen and glucose at the expense of other parts of the brain.

- Review of PET, fMRI, and MRS.

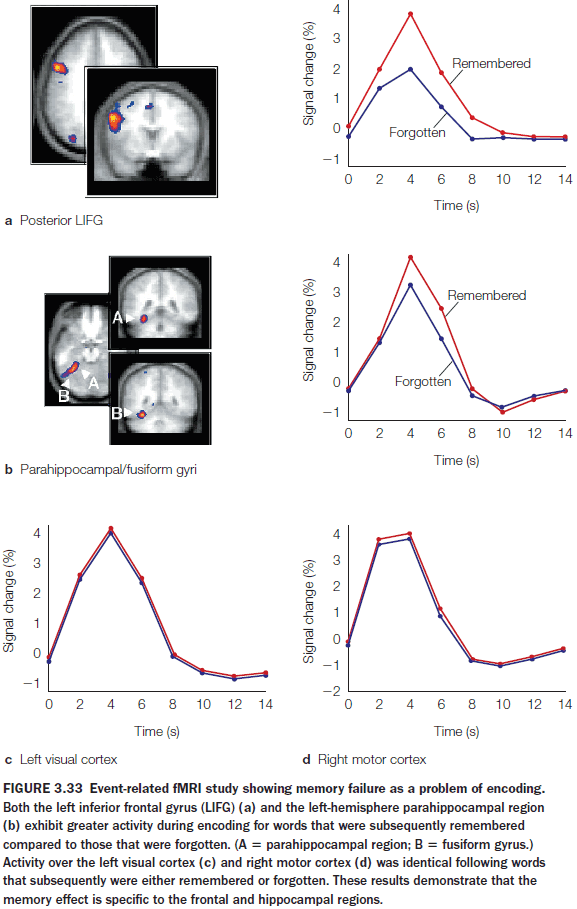

- Block design experiment: integrating neural activity over a block of time during which a participant performs multiple trials of the same type.

- Event-related design experiment: looking for an event across experimental trials.

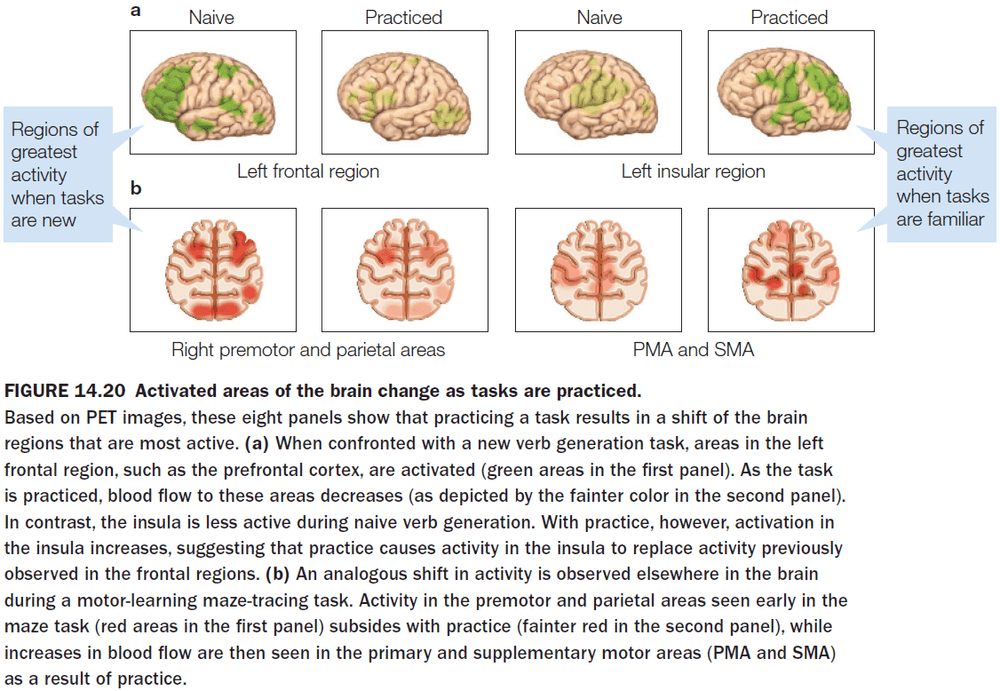

- Faster learning was associated with faster reduction in the correlation between two brain regions.

- The reason might be because the movement selection switches from being stimulus-driven to being internally-driven.

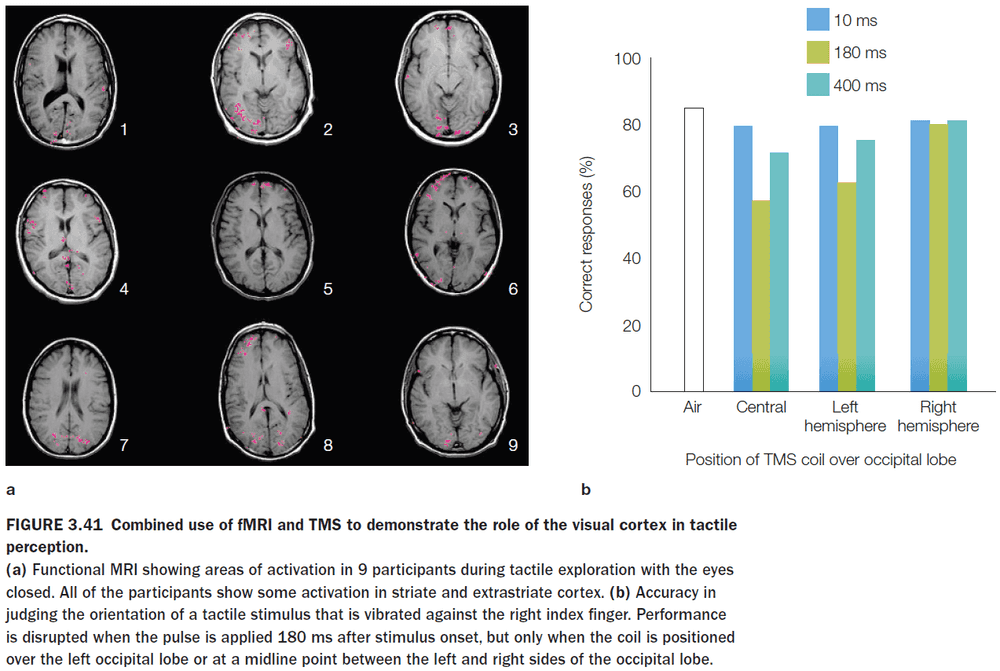

- An fMRI study showed that when participants kept their eyes closed, tactile object recognition led to pronounced activation of the visual cortex.

- This is unexpected because if the eyes are closed, we would expect the visual cortex to not be active due to no visual input.

- However, a follow-up study showed that if the visual cortex is temporarily stimulated through TMS, tactile object recognition becomes impaired.

- This suggests that the visual representations generated during tactile exploration were essential for inferring object shape from touch.

- This solves the Molyneux problem in that if you were born without sight and then gained it, you wouldn’t be able to identify objects by sight.

- The convergence of results obtained by using different methodologies frequently offers the most complete theories.

Part II: Core Processes

Chapter 4: Hemispheric Specialization

- Big questions

- Why is the brain split into two hemispheres?

- Do the differences in the anatomy of the two hemispheres explain their functional differences?

- Why do split-brain patients generally feel unified and no different after surgery, even though their two hemispheres no longer communicate with each other?

- Do separated hemispheres each have their own sense of self?

- Which half of the brain decides what gets done and when?

- In patient W.J., the corpus callosum was severed to treat his seizures. However, studies on cats, monkeys, and chimps with a severed corpus callosum had dramatically altered brain function afterwards.

- Puzzlingly, W.J. seemed to suffer no effects and only after extensive testing was it revealed that W.J.’s right hemisphere could do things that his left couldn’t do and vice versa.

- E.g. Objects presented to his left visual field couldn’t be named, since the language center of the brain is in the left hemisphere, but W.J. could move his left hand to say that he sees it.

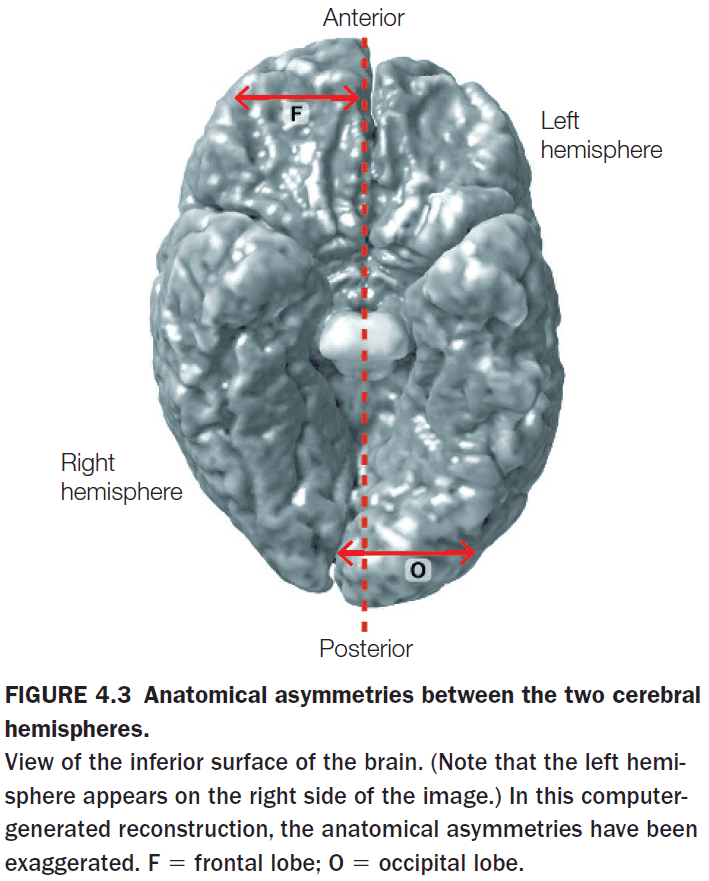

- Anatomy wise, the two hemispheres appear to be symmetrical and to be of the same size and surface area.

- However, the two hemispheres are offset with the right protruding in front and the left protruding in back.

- The right is chubbier in the frontal region and the left is chubbier in the posterior region.

- The most studied hemisphere specialization is language.

- Language appears to be left-hemisphere dominant.

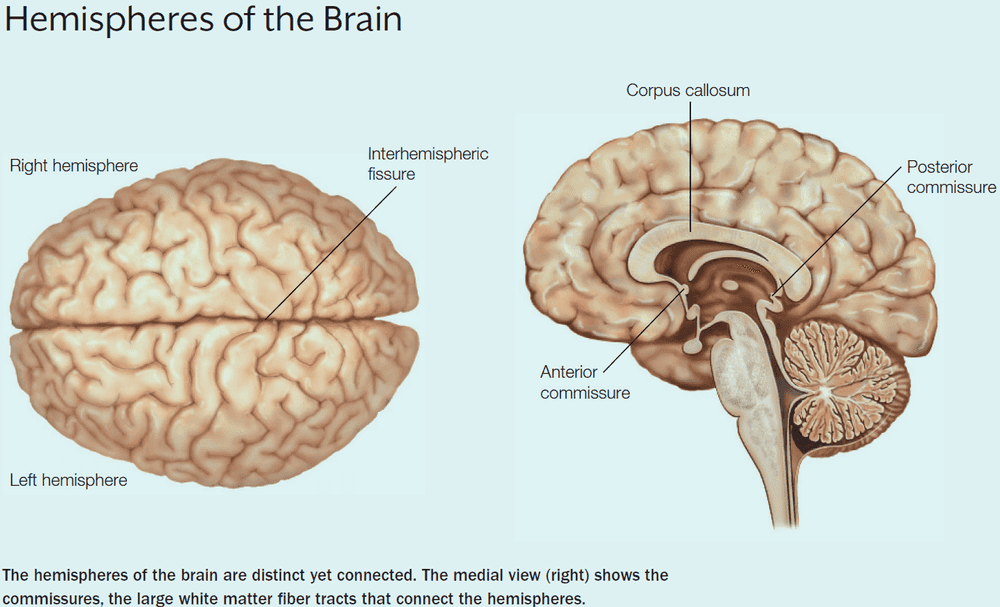

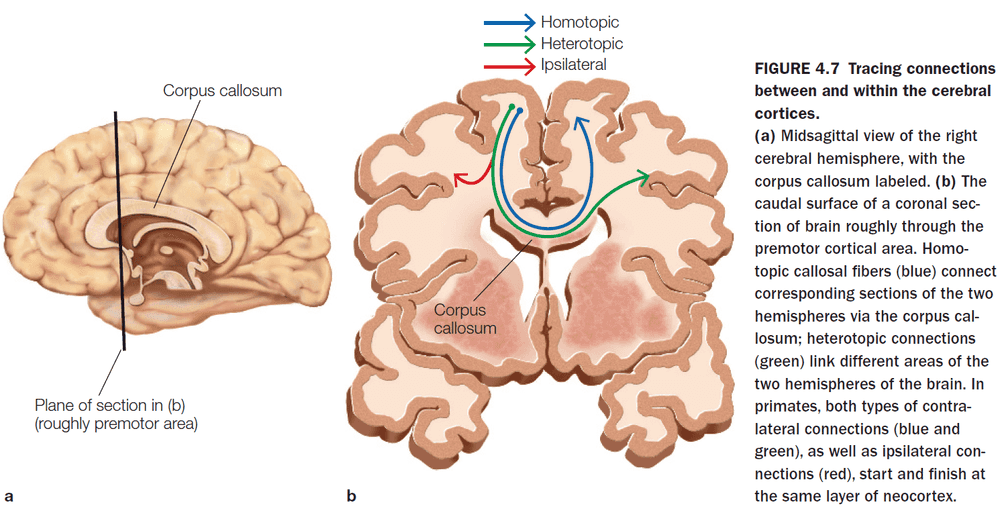

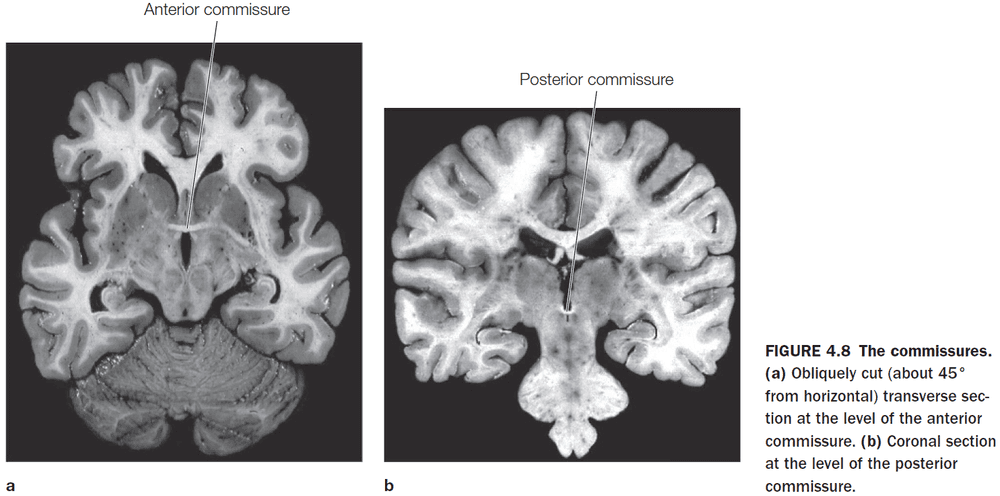

- The left and right cerebral hemispheres are connected by three structures

- Corpus callosum (CC)

- Anterior commissure

- Posterior commissure

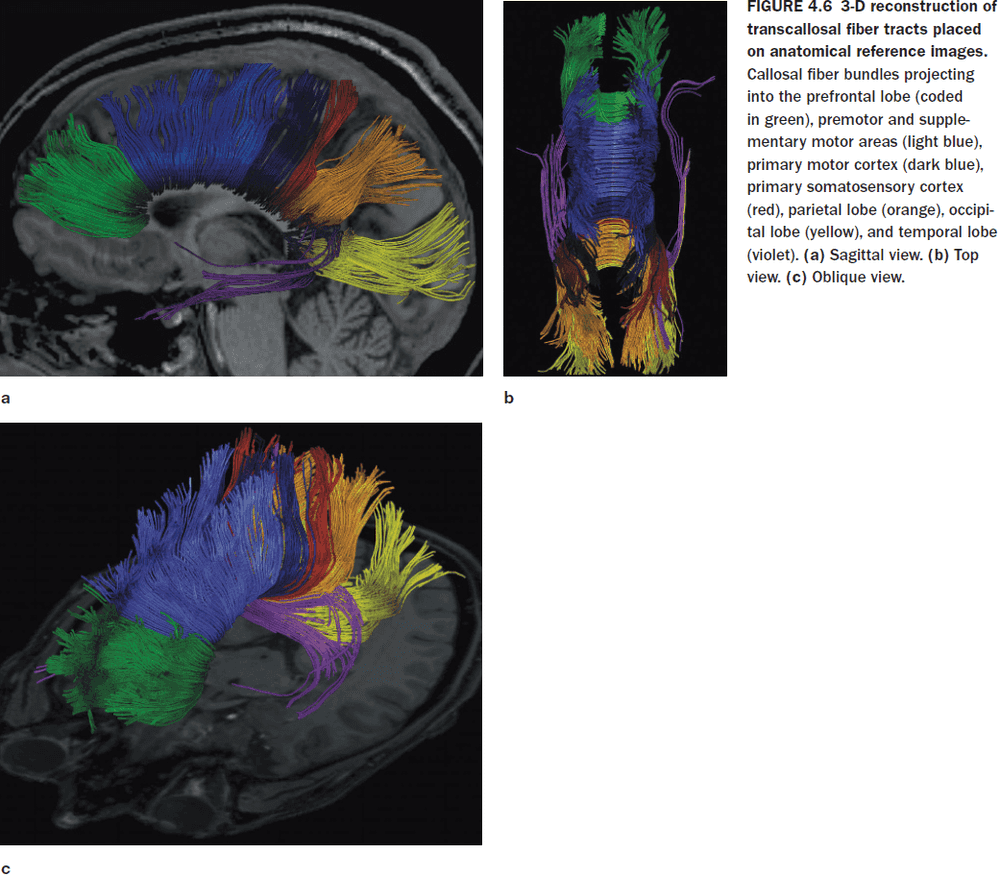

- As with the other parts of the brain, the CC maintains a topographic organization.

- Within the corpus callosum, there are two types of connections

- Homotopic: connections that go to a same region in the other hemisphere.

- Heterotopic: connections that go to a different region in the other hemisphere.

- Almost all of the visual information processed in the parietal, occipital, and temporal cortices is transferred to the opposite hemisphere through the posterior third of the CC.

- Motor and supplementary motor information is transferred through the middle third of the CC.

- The anterior commissure connects the two amygdalae and the posterior commissure contributes to the pupillary light reflex.

- The CC is the primary communication highway between the two hemispheres.

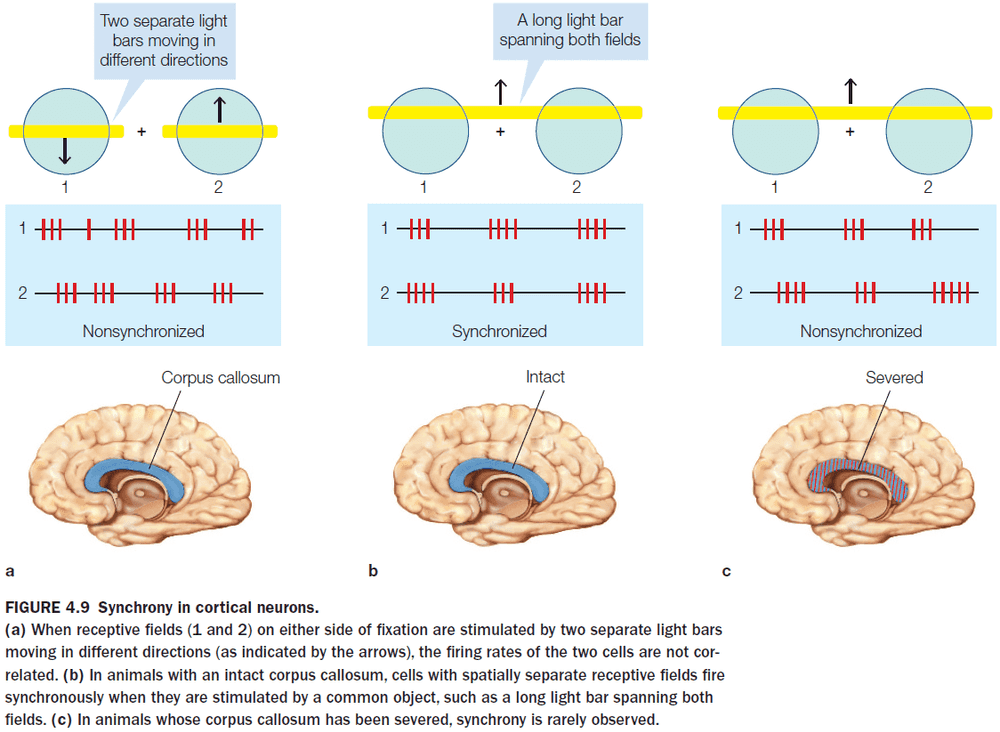

- Potential functions of the CC

- Enable information from both visual fields to contribute to receptive fields.

- Facilitate processing by pooling diverse inputs.

- Provide a means for each hemisphere to compete for control of current processing.

- In adults, the callosal connections are scaled-down version of what is found in children.

- The refinement of connections is a hallmark of callosal development.

- Methodological issues when evaluating split-brain patients

- The patients undergoing callosotomy already have abnormal brains due to seizures so they aren’t representative of normal brains.

- Some older callosotomies didn’t completely cut the CC since it was difficult to verify without MRI.

- Experiments have to be designed to eliminate cross-cuing (when one hemisphere cues the other hemisphere through its behavior).

- Cross-cuing behavior is sometimes obvious, such as one hand nudging the other, and sometimes it’s subtle, such as a facial muscle contraction or an eye movement.

- Cross-cuing isn’t intentional and is a way for the brain to communicate through means other than the CC.

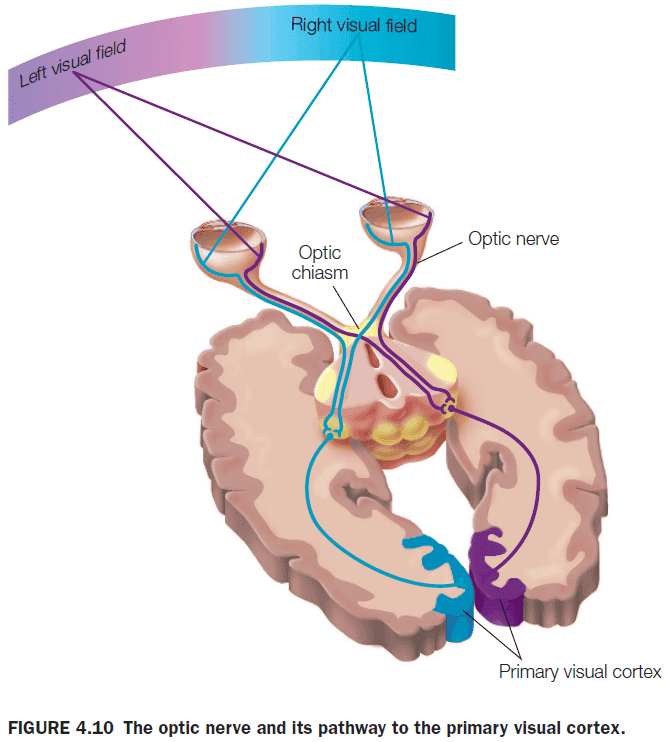

- The anatomy of the optic nerve allows visual information to be presented uniquely to one hemisphere or the other in split-brain patients. This isn’t the case for auditory or olfactory information.

- Functional consequences of the split-brain procedure

- Visual and tactile information presented to one half of the brain isn’t available to the other half.

- E.g. Patients can only name objects placed in their right hand and not the left hand.

- Confirms our knowledge that the left hemisphere is dominant for language, speech, and major problem solving and the right hemisphere is dominant for visuospatial tasks.

- No major changes in cognitive function.

- Patients can’t name or describe visual and tactile stimuli presented to the right hemisphere because the sensory information is disconnected from the left hemisphere.

- However, patients can still use nonverbal responses, such as left hand pointing, when information is presented to the right hemisphere.

- Visual and tactile information presented to one half of the brain isn’t available to the other half.

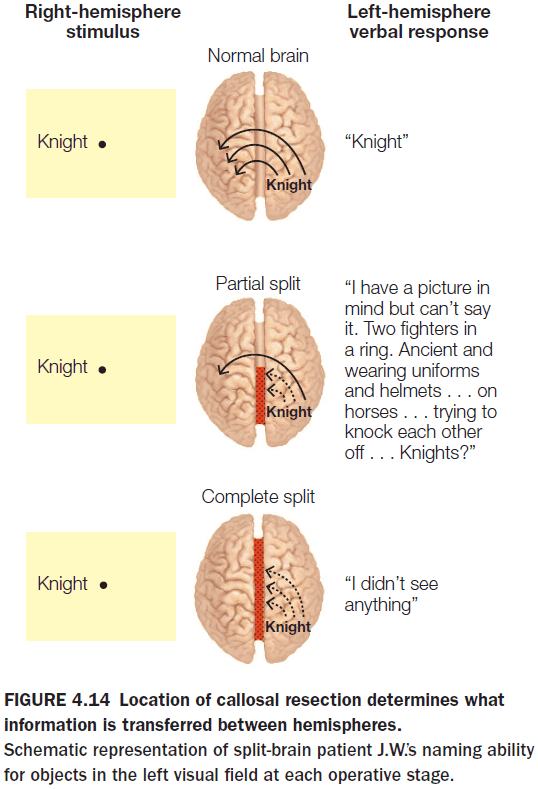

- Sometimes, surgeons only split part of the CC because they don’t want to split the entire CC if splitting only a part of it solves the epilepsy.

- This provides us with information on which parts of the CC are responsible for which function.

- Splitting the posterior half of the CC severely disrupts the transfer of visual, tactile, and auditory sensory information but retains the ability to transfer higher-order information.

- E.g. Patient J.W. was shown the word “sun” to their left hemisphere and a black-and-white drawing of a traffic light to their right hemisphere. When asked what they saw, J.W. correctly saw the word “sun” and couldn’t identify the traffic light drawing. However, J.W. could recognize that the drawing had to do with cars and recognized that it involved colors. In the end, J.W. correctly inferred that the drawing was of a traffic light.

- Closer examination revealed that the left hemisphere was receiving higher order cues about the stimulus without having access to the sensory information about the stimulus itself.

- The anterior part of the CC transfers semantic information about the stimulus but not the stimulus itself.

- When attempting to understand the neural bases of language, it’s useful to distinguish between grammatical and lexical function.

- Grammar: the rule-based system for ordering words to help communication.

- E.g. In English, the typical order of a sentence is subject-action-object.

- Lexicon: the mind’s dictionary.

- E.g. The word “dog” is associated with a dog but so is “Hund”, “kutya”, and “cane”.

- This distinction is more apparent when trying to learn a new language and it’s predicted that grammar is more localized and discrete whereas the lexicon’s location is more elusive and more difficult to damage completely.

- Language and speech are rarely present in both hemispheres; they are in either one or the other.

- However, both hemispheres show the word superiority effect where English readers are better able to identify letters in real words than the same letter in pseudowords.

- The reasoning is because pseudowords don’t have lexical entries so letters in their strings don’t receive the additional processing benefit bestowed on words.

- There appear to be two lexicons, one in each hemisphere, and they’re both organized and accessed differently.

- While the left hemisphere is dominant for most language capabilities, the right hemisphere appears to handle the emotional content, or emotional prosody, of language.

- The left hemisphere is biased toward recognizing one’s own face, while the right hemisphere is biased towards recognizing familiar faces.

- Some type of spatial information is transferred and integrated between the two hemispheres, since both split-brain patients and normal patients can transfer their attention to either visual field.

- This suggests that the two hemispheres rely on a common orienting system to maintain a single focus of attention.

- Even in split-brain patients, they can’t divide their attention into two as the integrated spatial attention system remains intact following cortical disconnection.

- Each hemisphere uses the same available resources, but at different stages of processing.

- E.g. The left hemisphere is better at using color to search for an object but the right hemisphere is better at processing upright faces.

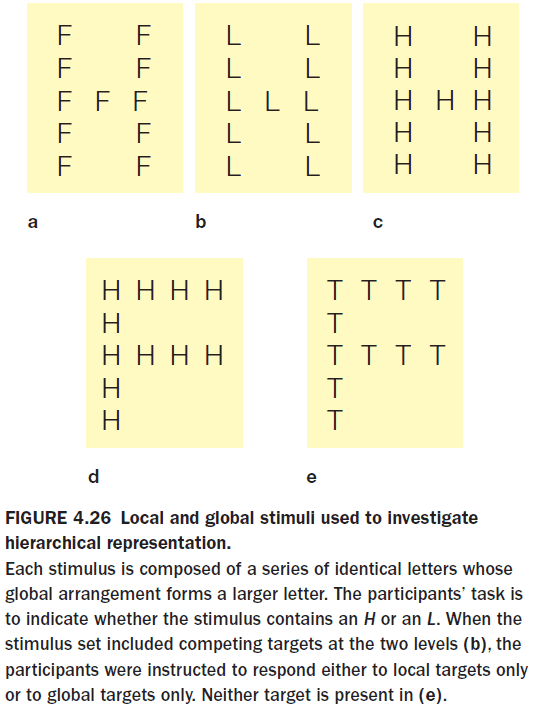

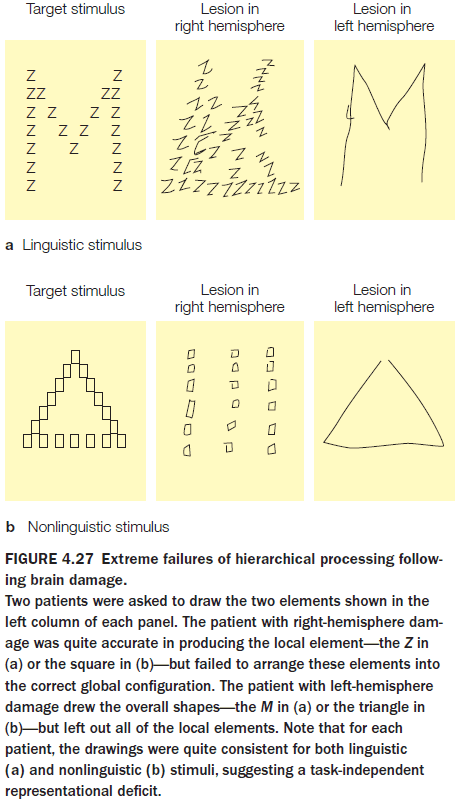

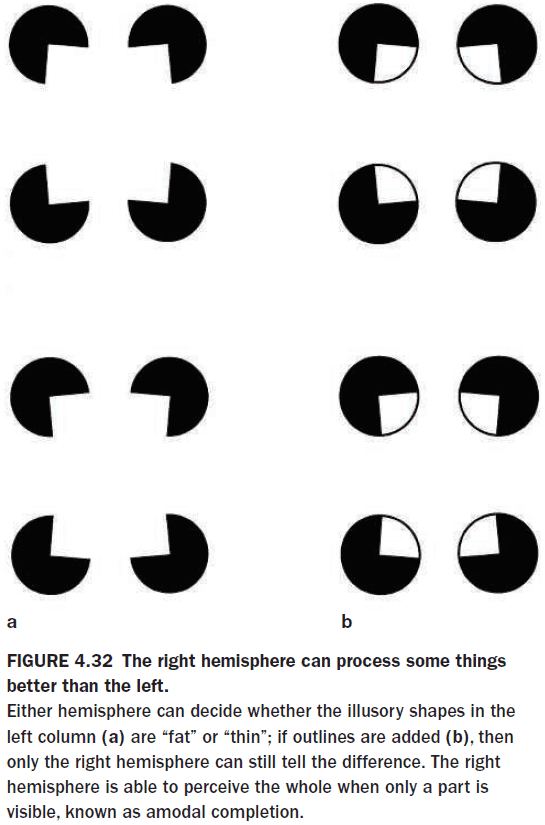

- In testing the brain’s local and global information processing, experiments show that the left hemisphere is better at representing local information and the right hemisphere is better with global information.

- Both hemispheres can abstract either level of representation, but they differ in how efficiently they handle each level.

- The right is better at the big picture, the left is more detail oriented.

- Theory of mind: the ability to understand that other people have thoughts, beliefs, and desires.

- Several fMRI studies show that the critical component of the theory of mind, the attribution of beliefs to another person, is localized to the right hemisphere.

- This is shocking because this means that split-brain patients should talk as if they lack social and moral reasoning but they talk as if they are normal.

- The left hemisphere deals with speaking and without information about the theory of mind, the patient should speak without regarding other people.

- So why don’t split-brain patients act like severely autistic individuals?

- They actually do under experimental conditions. Split-brain patients answer immorally compared to normal patients but are shocked at their own answer.

- E.g. Suppose a friend accidentally poisons her family by mixing bleach and ammonia, should she be held morally responsible? Most people answer no because the friend intended no harm and had a false belief. Split-brain patients, however, answer yes because they judge the friend based on the results.

- Only the left hemisphere can trigger voluntary facial expressions, but both hemispheres can trigger involuntary expressions.

- A hallmark of human intelligence is our ability to make causal interpretations about the world.

- E.g. If the ground is wet and the sky is gray, what happened?

- In split-brain patients, their intelligence remains unchanged but this is only true for the speaking left hemisphere. The right hemisphere suffers from impoverished intellectual abilities and problem-solving skills.

- This impoverishment is due to the left hemisphere’s specialized ability to find causal inferences and interpretations, abilities the right hemisphere never had.

- We refer to this unique specialization of the left hemisphere as the interpreter.

- Experiments show that the speaking left hemisphere always offers some kind of rationalization to explain actions that were initiated by a motivation unknown to the left hemisphere.

- E.g. When split-brain patient P.S. was given a command to stand up but only to the right hemisphere, P.S. stood up. When the experimenter asked P.S. why he stood up, P.S. responded “Oh, I felt like getting a Coke.” If his CC was intact, P.S. would’ve responded that he stood up because he was told to do so.

- A constant finding in the testing of split-brain patients is that the left hemisphere never admits ignorance about the behavior of the right hemisphere. It always makes up a story to fit the behavior.

- The interpreter also will explain the mood caused by the experiences of the right hemisphere, not only its actions.

- Emotional states appear to be transferred subcortically so severing the CC doesn’t prevent emotional states from being transferred between the hemispheres.

- The left hemisphere is better at making inferences about semantic relationships and cause and effect, it doesn’t have a better memory or a better lexicon than the right hemisphere.

- This is shown in an experiment where participants guess which of two events would happen next. Event red appears 75% of the time and event green appears 25% of the time.

- There are two strategies to this experiment

- Matching: matching your guesses to the frequency distribution of the events.

- E.g. Guessing red 75% of the time and green 25% of the time.

- Maximizing: guessing the event with the highest probability all of the time.

- E.g. Guessing red 100% of the time.

- Matching: matching your guesses to the frequency distribution of the events.

- Non-human animals, such as rats and goldfish, maximize, while humans match.

- The result is that non-human animals perform better than humans on this task.

- Neural networks also fall prey to either strategy and may either guess the output training distribution or only guess one output.

- In split-brain patients, the left hemisphere uses the matching strategy while the right hemisphere uses the maximizing strategy.

- This furthers the case that the left hemisphere attempts to make inferences and to make complicated hypotheses about the task, while the right hemisphere approached the task in the simplest possible manner.

- While the left hemisphere has the ability to make causal inferences, the right hemisphere is better at judgments of causal perception.

- This causes problems, however, when no causal pattern exists and this is probably the cause of some cognitive biases.

- For the interpreter, facts are helpful but not necessary. It has to explain whatever is at hand and it uses the first explanation that makes sense.

- The interpreter is a powerful mechanism that makes investigators wonder how often our brains make spurious correlations as we attempt to explain our actions, emotional states, and moods.

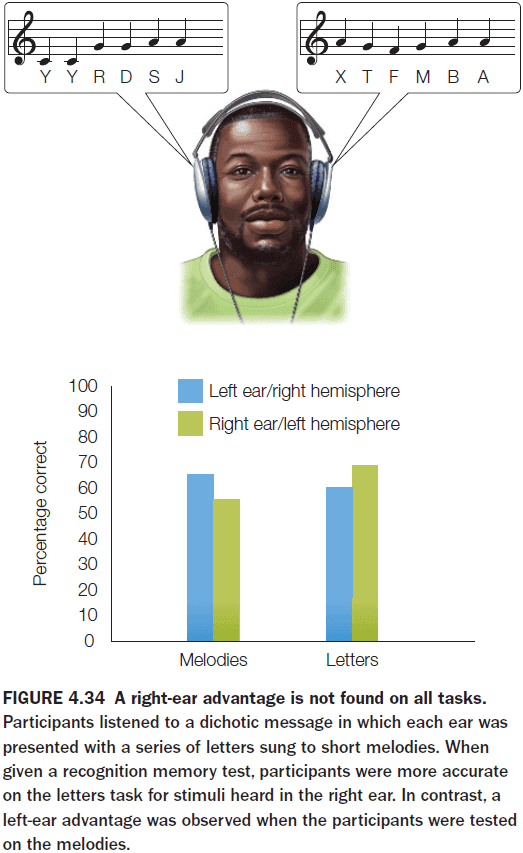

- Auditory pathways aren’t as strictly lateralized as visual pathways.

- The right-ear advantage effect is a bias seen in the dichotic listening task where participants consistently repeat words presented to the right ear.

- This matches the expectation that the left hemisphere is dominant for language.

- There’s also the left-ear advantage effect where the left ear is biased towards melodies.

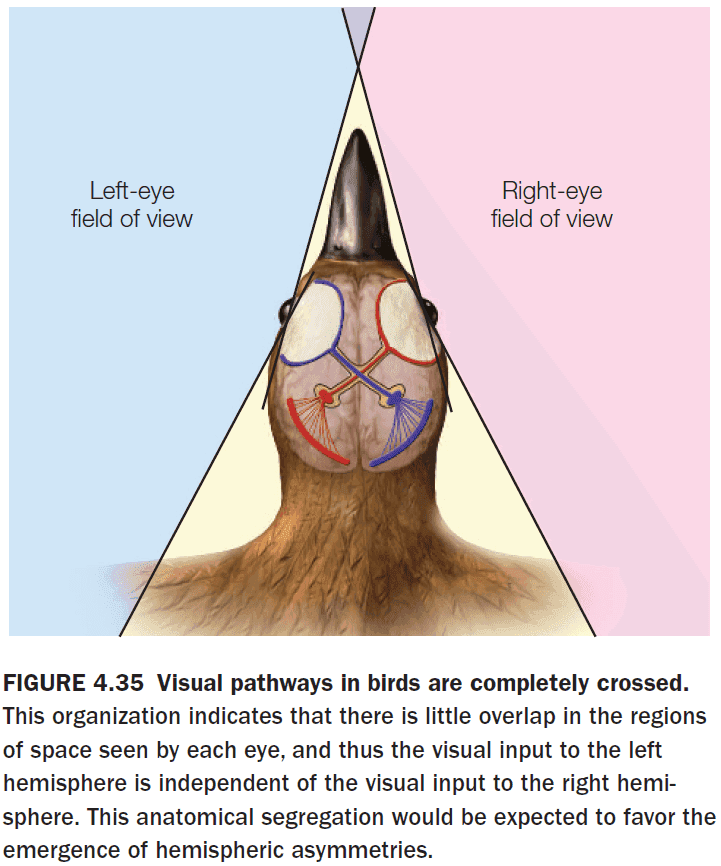

- Hemispheric specialization isn’t a unique human feature and is present in all vertebrates.

- E.g. Fruit flies, octopuses, bees, spiders, crabs.

- Interestingly, in birds, almost all of the optic fibers cross at the optic chiasm, probably reflecting the fact that there’s little overlap in the visual fields of birds due to lateral eye placement.

- Also, birds lack a CC which results in functional asymmetries.

- E.g. Song production is localized to the left hemisphere.

- Just as humans show handedness or the favoring of either the left/right hand, dogs and cats show pawedness.

- Our best evidence suggests that lateralization might have been facilitated by a lack of callosal connections.

- The resulting isolation would’ve promoted divergence among functional capabilities, resulting in cerebral specialization.

- Introduction to the idea that the brain uses a small-world architecture.

- Advantages of a modular brain

- More energy efficient

- Parallel processing

- Increased robustness

- More adaptable

- Modules emerge when there’s pressure to minimize wiring cost.

- Much of what we learn from clinical tests of hemispheric specialization tells us less about the computations performed by each hemisphere, and more about the tasks themselves.

- Each hemisphere has some competence in every cognitive domain, but the competence varies between them.

Chapter 5: Sensation and Perception

- Big questions

- How is information in the world carried by light, sound, smell, taste, touch, translated into neuronal signals by our sense organs?

- How might neural plasticity in sensory cortex manifest itself?

- Most of our perceptions and behaviors never reach our conscious awareness and those that do aren’t exact replicas of the stimulus.

- E.g. Optical illusion and the color magenta.

- Sensation: the initial activation of the nervous system for translating information about the environment into patterns of neural activity.

- Percept: the mental representation of the stimulus, accurate or not.

- Perception: the process of constructing the percept.

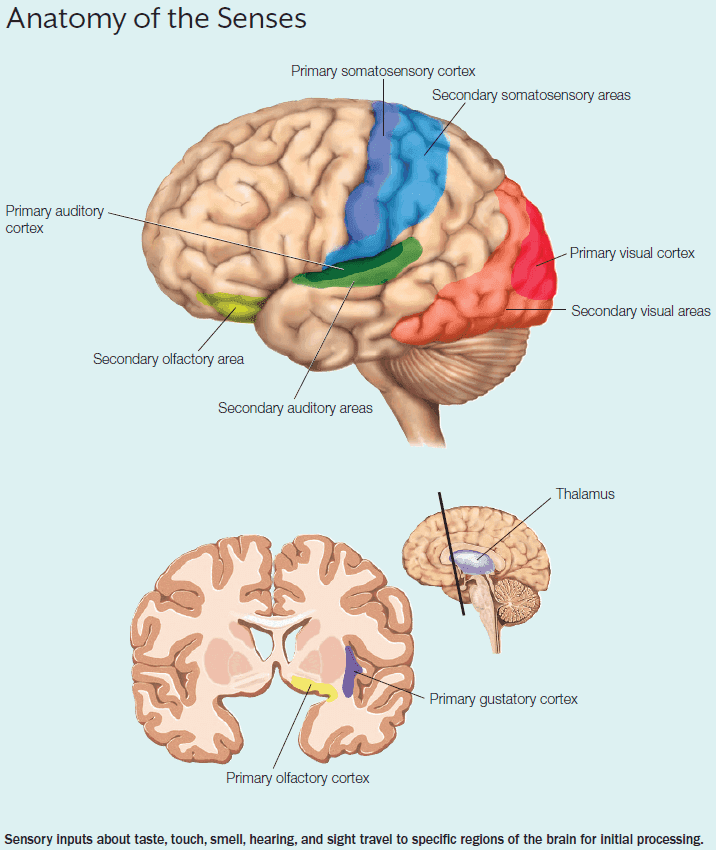

- Information from each sensory organ follows the same general pathway except for olfaction.

- The general pathway

- Specialized receptor cells

- Specific sensory nerve pathway

- Thalamus

- Primary sensory region

- Secondary sensory region

- Olfaction skips the thalamus and goes straight to the primary olfactory cortex.

- Shared receptor properties

- Limited in range of stimuli captured affecting precision.

- E.g. Our eyes can only see between 400-700 nm of the electromagnetic spectrum.

- There’s a minimum intensity threshold.

- Adapts as the environment changes.

- The longer the stimulus continues, the less frequent the APs are.

- E.g. Not feeling the clothes that you’re wearing.

- Limited in range of stimuli captured affecting precision.

- Acuity: how well we can distinguish among stimuli within a sensory modality.

- Perception is mainly concerned with changes in sensation.

- Many creatures can carry out exquisite perception without a cortex, so why do we have a cortex?

- The answer may be to support flexible behavior.

- At all levels of the sensory pathways, neural connections go in both direction.

- These feedback connections appear to provide a way for the cortex to control the flow of information from the sensory systems.

- Review of the neural pathways of olfaction.

- We don’t know how the activation of olfactory receptors leads to the perception of specific odors.

- The primary olfactory cortex habituates (adapts) quickly to new smells.

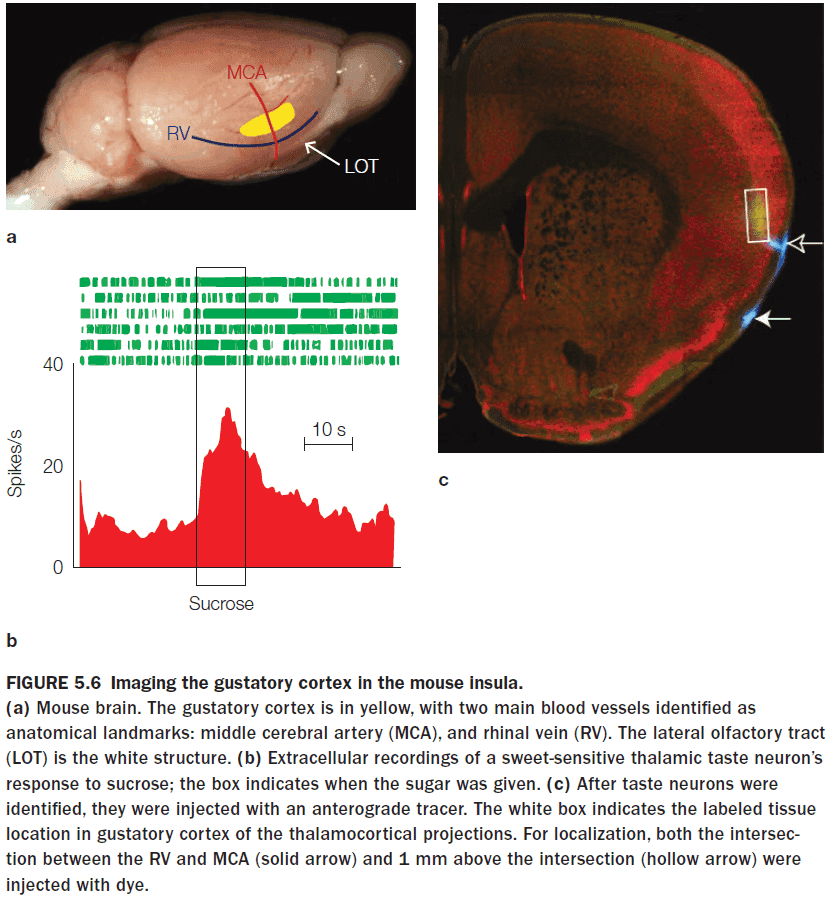

- Review of the neural pathways of gustation.

- The gustotopic map is maintained in the cortex with clusters found for bitter, sweet, umami, and salty.

- No sour cluster was found but it may be distributed over multiple pathways.

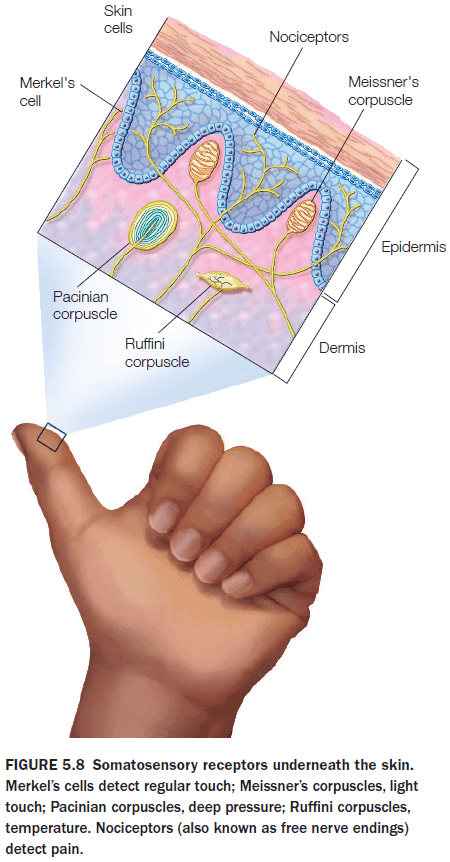

- Review of the neural pathways of somatosenation.

- There are two types of pain receptors: fast and slow.

- The relative amount of cortical representation in the sensory homunculus corresponds to the relative importance of somatosensory information for that part of the body.

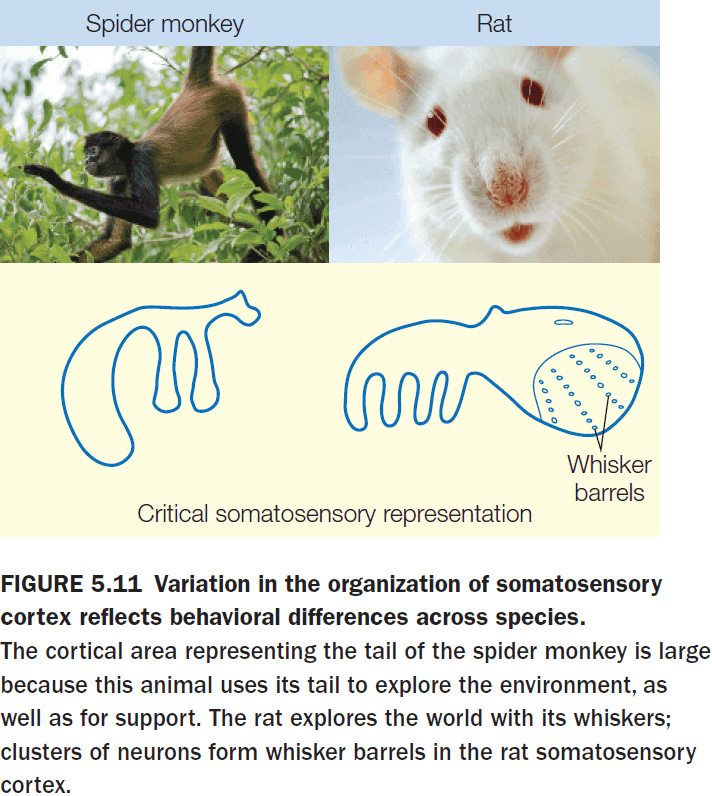

- Somatotopic maps show considerable variation across species but the general rule, that more important body parts have a larger cortical representation, still rules.

- E.g. Spider monkeys have a larger area for their tail and rats have a larger area for their whiskers.

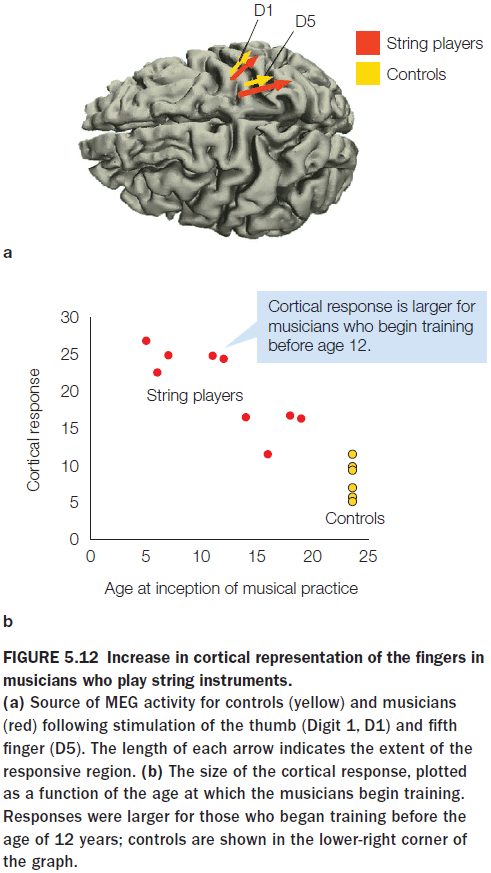

- Somatosensory representations exhibit plasticity, showing variation in extent and organization as a function of individual experience.

- Experiments on the phantom limb phenomenon and the rubber hand illusion suggest that the brain can integrate visual input and direct stimulation of the somatosensory cortex to create the multisensory illusion of ownership, challenging the idea that the human brain is stable in adulthood.

- Review of the neural pathways of audition.

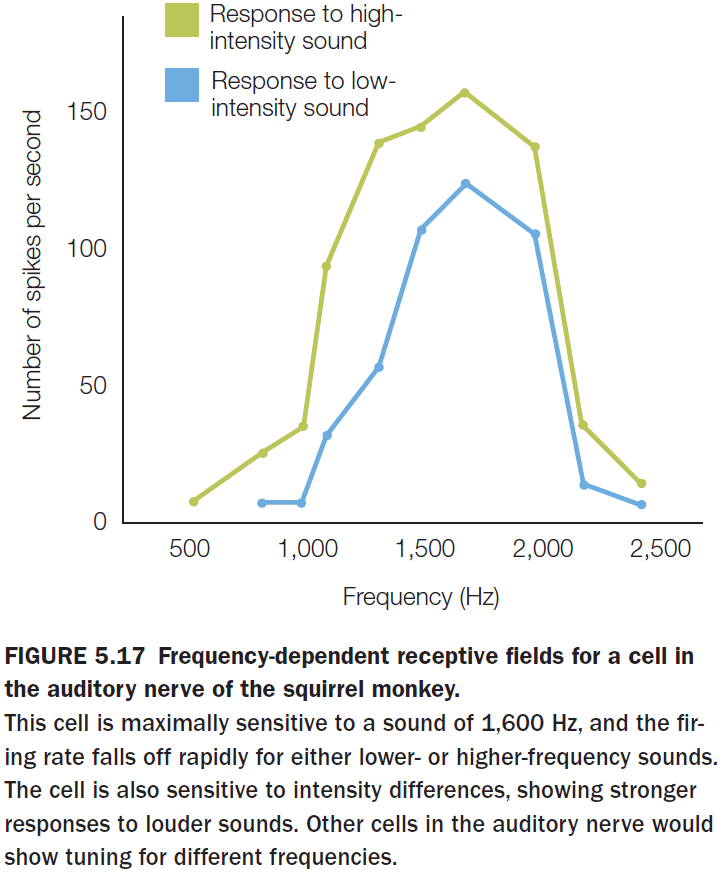

- Early in the auditory system, in the cochlea, there’s already the processing of information in the form of a tonotopic map.

- Our auditory system is most sensitive to sounds in the 1-4 kHz range and this reflects the range of human communication.

- Other species also are sensitive to different frequencies which also reflects their communication.

- E.g. Elephants are sensitive to low-frequency sounds and mice are sensitive to high-frequency sounds.

- These species-specific differences likely reflect evolutionary pressures that arose from the capabilities of different animals to produce sounds.

- The tuning of individual neurons becomes sharper as we move through the auditory system.

- While the global organization of A1 is tonotopic, the local organization is quite messy with adjacent cells frequently showing very different tuning.

- The computational goals of audition is to determine the what and where of sound signals.

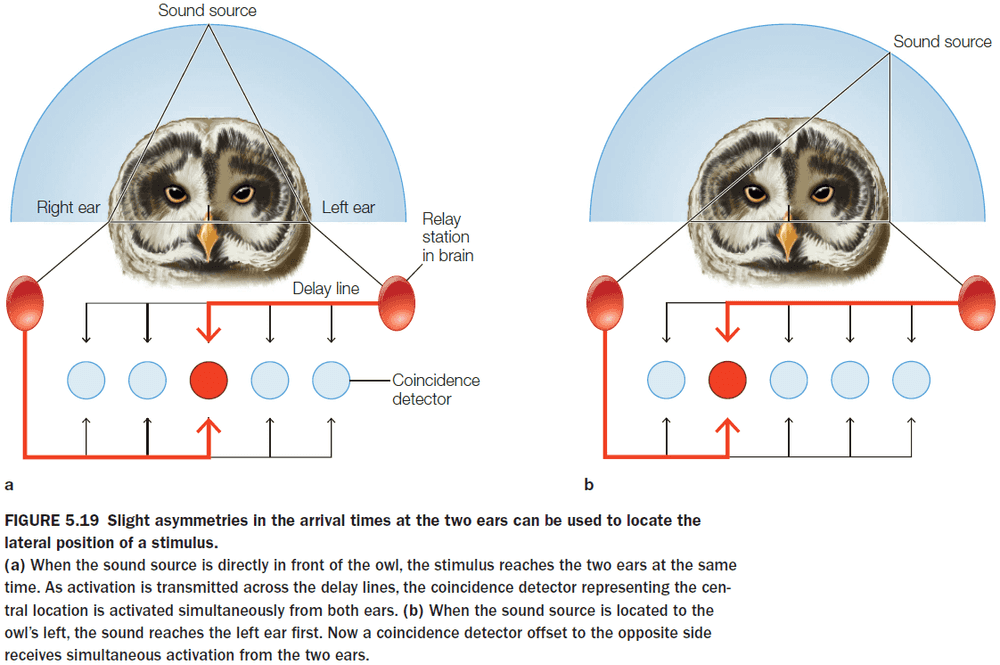

- The auditory system uses two cues to localize sounds

- Difference in timing (interaural time)

- Difference in intensity

- One way to compute these differences is to use a coincidence detector.

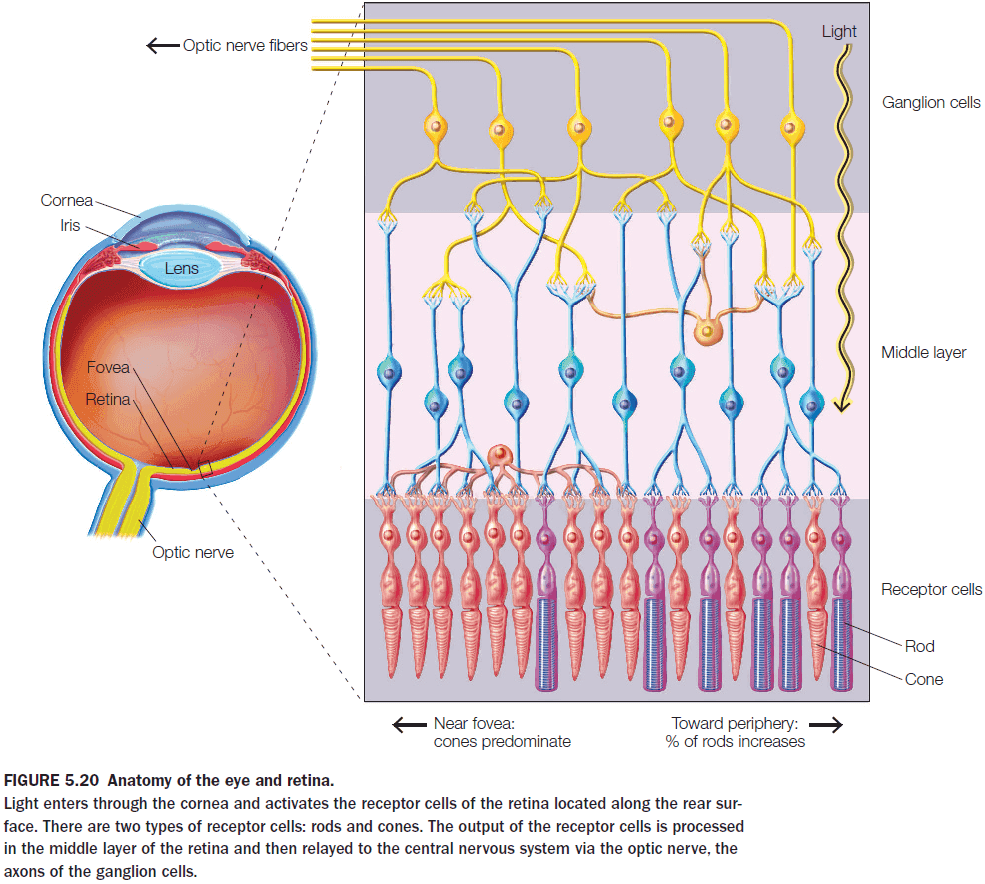

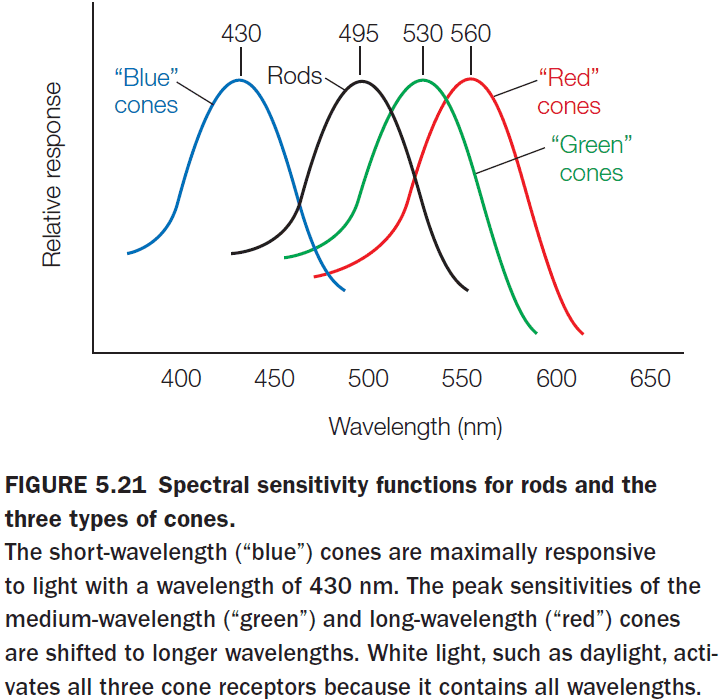

- Review of the neural pathways for vision.

- Both audition and vision are important for perceiving information at a distance.

- The retina’s photoreceptors don’t fire APs and instead use a graded potential to transmit information.

- The retina compresses visual information as it goes from 260 million photoreceptors to 2 million ganglion cells.

- Analogous to the auditory system, the visual system also identifies the what and where of objects.

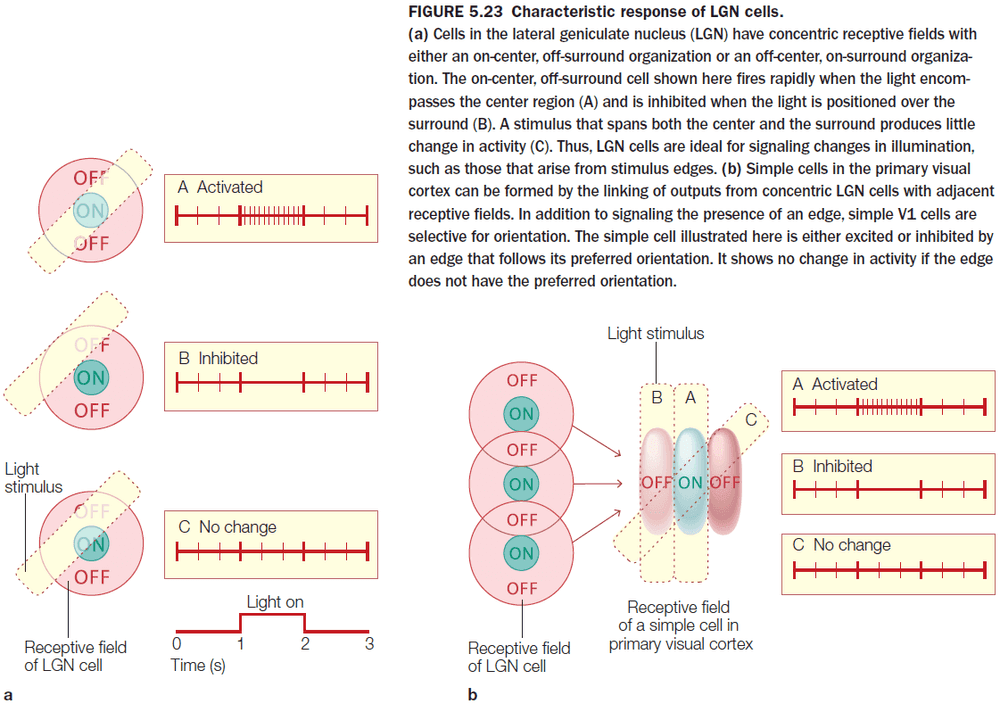

- Also like other sensory systems, the receptive fields of visual cells form an orderly mapping between the external dimension (spatial location) and the neural representation of that dimension known as retinotopic maps.

- The observation that cells respond to changes in light clarify a fundamental principle of perception: the nervous system is interested in change.

- E.g. We recognize an elephant not by its gray body, but by the contrast of the gray edge of its shape against the background.

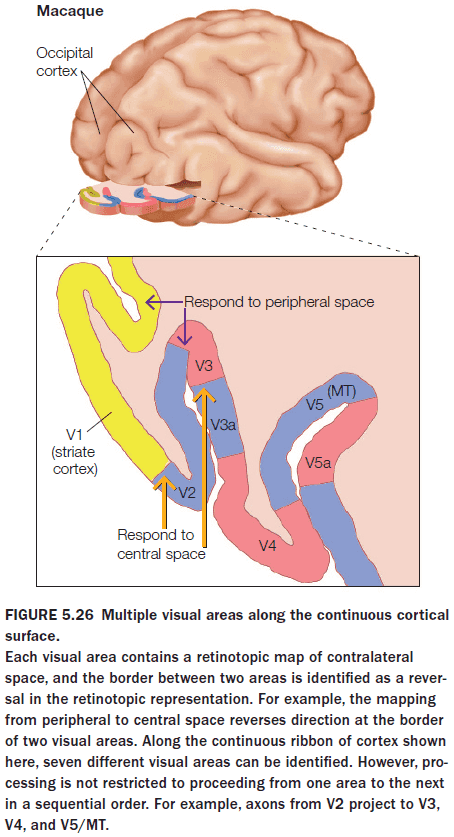

- As information moves through the visual system, the optimal stimulus becomes more complex and the receptive fields become larger.

- Why does the brain have so many visual areas? One answer is hierarchy.

- Each area, with a unique representation of the stimulus, successively elaborates on the representation derived by processing in earlier areas.

- However, this isn’t true as there are feedback connections in the visual system.

- An alternative view is that vision is an analytic process, using a divide-and-conquer strategy to manage visual information.

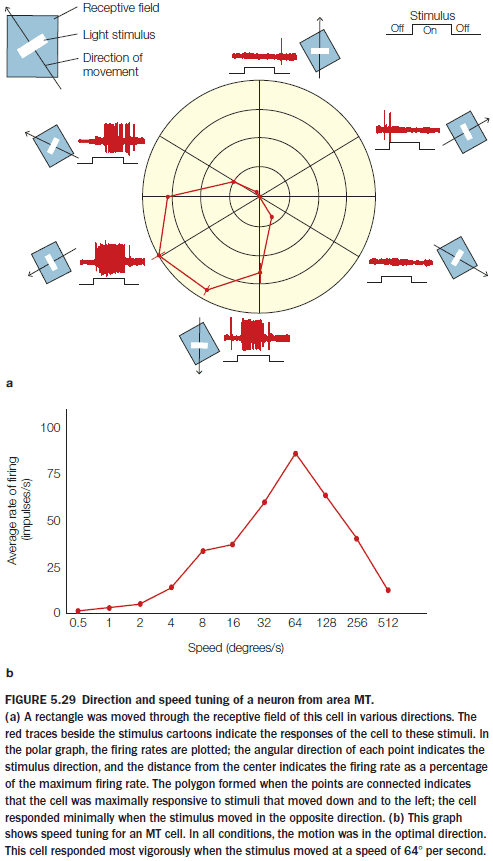

- Evidence supports the analytic process hypothesis as cells in area MT are sensitive to stimuli that

- Fall within its receptive field

- Move in a certain direction

- Move at a certain speed

- Humans have visual areas that do not correspond to any region in our close primate relatives.

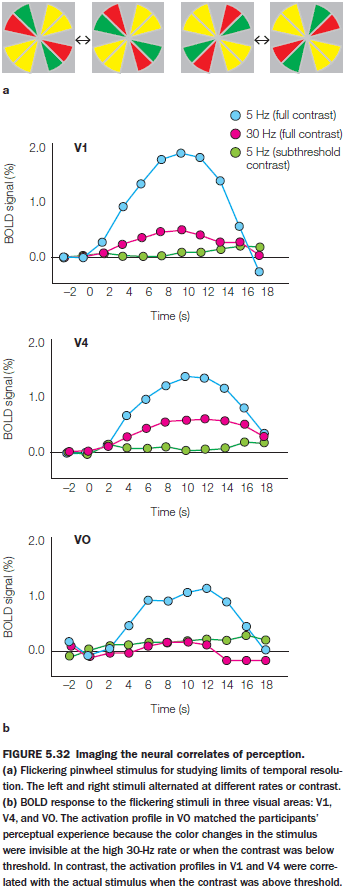

- At what stage of processing does sensory stimulation become a percept, something we experience phenomenally?

- One way to answer this question is to use illusions.

- E.g. The flicker fusion where a disk colored green on one side and red on the other is flipped. At 25 Hz, the percept is a fused color of a constant, yellowish white disk.

- Where in the visual system does it fail to keep up with the flickering stimulus? Does the breakdown occur early or late in the system?

- An experiment showed that early parts of the visual system can differentiate between the colors at high rates but the late parts can’t.

- Although the information is sensed accurately at earlier stages within the visual system, conscious perception, at least of color, is more closely linked to higher-area activity.

- There is a double dissociation for this idea as stimulation of higher visual areas results in participants viewing the cell’s preferred stimulus. In the experiment’s case, the preferred stimulus was a color.

- How does the brain combine our separate senses into a unified multisensory experience?

- There are illusions of multisensation such as the McGurk effect.

- E.g. Given a video of someone saying “ba” but the audio is replaced with “fa”, the brain perceives “ba” even though it hears “fa”.

- In the McGurk example, visual input overrules auditory input as the brain gives greater weight to more reliable signals.

- The weighting idea captures the idea that the system is flexible and that there isn’t a predefined bias towards any sense. The bias is towards reliable signals.

- Vision may seem like the sense that dominates since it’s the most reliable and contains the most information but that isn’t always the case.

- E.g. When walking in the dark, we focus more on sounds as it’s more reliable and it provides more information since vision is poor in the dark.

- Where is information from different sensory systems integrated in the brain?

- Integration happens in the superior colliculus and superior temporal sulcus.

- Integration requires that the different stimuli be coincident in both space and time.

- Auditory and visual stimuli can enhance perception in the other sensory modalities.

- E.g. Applying TMS over the visual cortex generates illusory flashes of light (phosphenes) above a threshold. If we set the intensity level of TMS to just below the threshold and no stimulus is given, no phosphenes are seen. If, however, we provide an auditory stimulus, then phosphenes are seen. This provides evidence that auditory stimulation increases visual perception.

- Synesthesia: the mixing of senses.

- E.g. When words have a taste or when numbers have colors.

- While synesthetic associations aren’t consistent across individuals, they’re consistent over time for an individual.

- Testing for synesthesia is difficult since it’s such a personal experience but we can test it using a modified version of the Stroop task.

- We can modify the Stroop task by checking whether the person responds faster if the color of the word matches their synesthetic color. To normal people, different colors don’t matter.

- Evidence shows that synesthesia is a real condition and that it’s objectively testable.

- Synesthesia appears to be a distributed condition affecting the general sensory pathways, rather than being localized, but no general consensus has been reached.

- Cortical plasticity = functional reorganization

- Primary sensory areas exhibit experience-induced plasticity during defined windows of early life, known as critical periods.

- The brain requires external inputs during these periods to establish an optimal neural representation of the surrounding environment.

- E.g. The visual system needs input to properly develop the thalamic connections to cortical layer IV.

- E.g. Shutting one eye in cats and monkeys weeks and months after birth results in the failure to develop normal ocular dominance columns in the primary visual cortex. This change was permanent. Applying the same change to adult animals has minimal effect.

- As attention is directed to one modality, activation decreased in other sensory systems.

- Mechanisms of cortical reorganization

- Rapid changes are due to the sudden reduction in inhibition that normally suppresses inputs from neighboring regions and from weak connections.

- Changes over a period of days involves changes in the efficacy of existing circuitry such as denervation hypersensitivity.

- Cochlear implants work by directly stimulating the auditory nerve.

Chapter 6: Object Recognition

- Big questions

- What processes lead to the recognition of an object?

- How is information about objects organized in the brain?

- Does the brain recognize all types of objects using the same process?

- Patient G.S. was unable to recognize objects even though his vision was intact.

- The act of perceiving also touches on memory.

- E.g. To recognize a photograph of your mother requires a correspondence between the current percept and an internal representation of previously viewed images of your mother.

- Four major concepts of object recognition

- Use terms precisely.

- E.g. See vs perceive. G.S. could see the pictures but couldn’t perceive the object.

- Object perception is unified.

- Perceptual capabilities are enormously flexible and robust.

- E.g. We can recognize an object regardless of viewpoint, illumination, and size.

- The product of perception is intimately interwoven with memory.

- Use terms precisely.

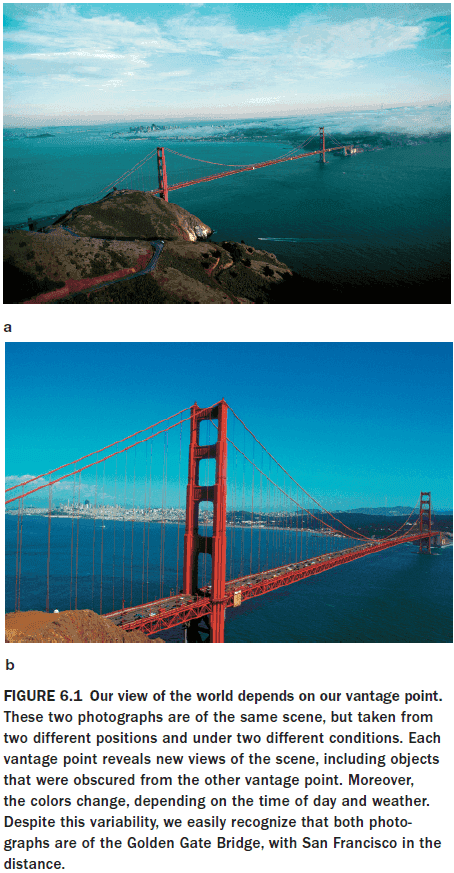

- Object constancy: our ability to recognize an object regardless of the situation.

- Sensation, perception, and recognition are distinct phenomena.

- Visual information coming from an object varies in three factors

- Viewing position

- Illumination

- Context

- The visual system is adept at separating changes caused by shifts in viewpoints from changes to an object itself and visual illusions can exploit this fact.

- Object recognition must be both general enough to support object constancy and specific enough to pick out slight differences in objects.

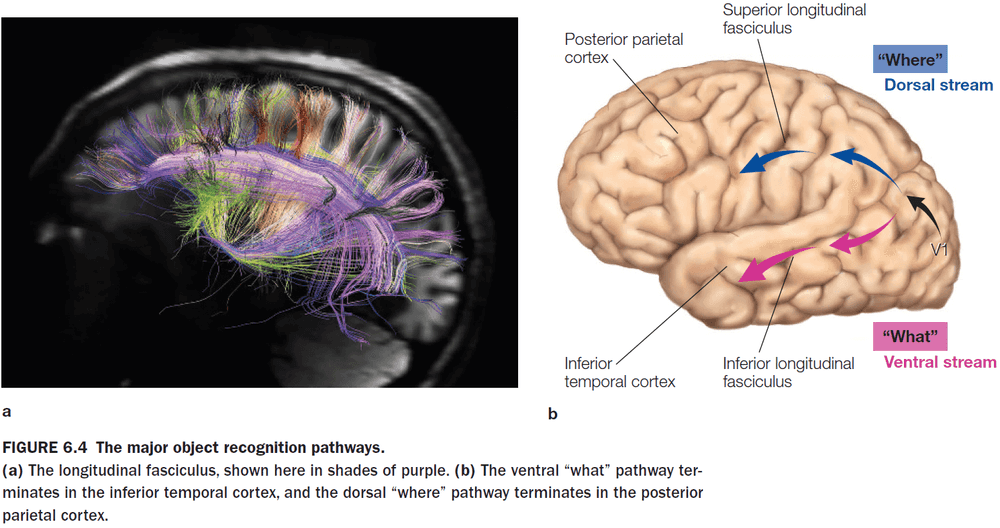

- Review of the dorsal (where) and ventral (what) visual streams.

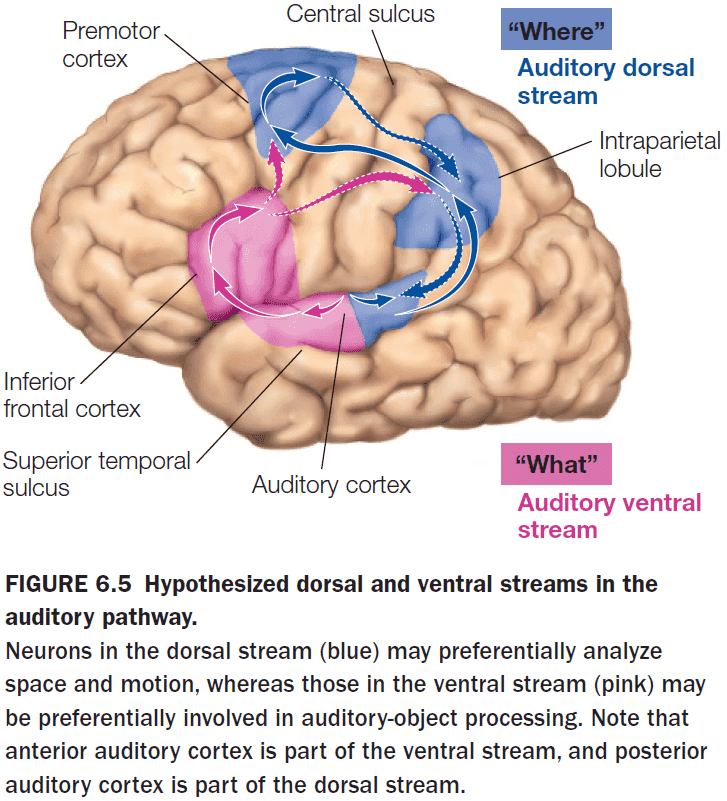

- The separation of “what” and “where” pathways isn’t limited to vision and occurs in the auditory system too.

- The anterior part of the primary auditory cortex is specialized for “what” and the posterior part is specialized for “where”.

- Neurons in both the temporal and parietal lobes have large receptive fields, but the properties of those receptive fields differ.

- Neurons in the parietal lobe have receptive fields tuned for a stimulus’s location on the retina (40% fovea, 60% periphery), while neurons in the temporal lobe have receptive fields tuned only for the fovea (100% fovea).

- This suggests that object recognition focuses mostly on the light hitting the fovea and ignores peripheral signals.

- Further along the “what” processing stream, neurons have a preference for more complex features.

- E.g. Human body parts, apples, flowers, or snakes.

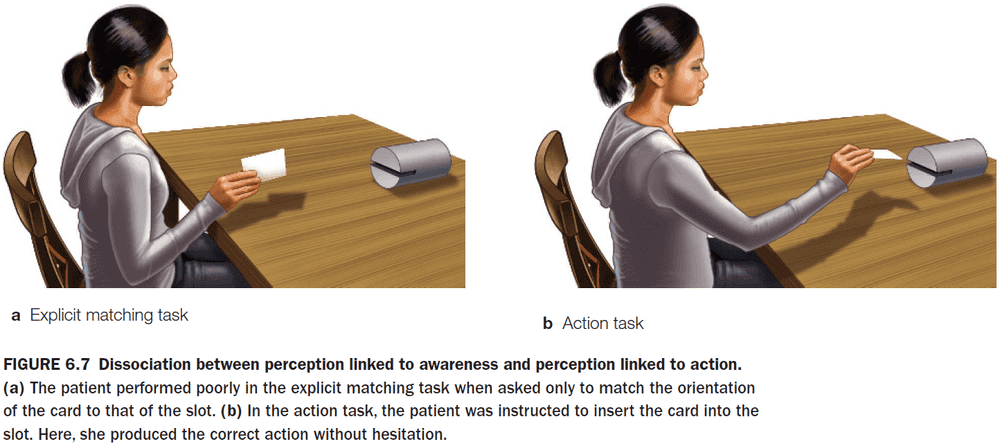

- There appears to be a difference between perception for identification and perception for action.

- Visual agnosia: a deficit in recognizing objects even when the processing for analyzing basic properties such as shape, color, and motion are intact.

- E.g. Patient D.F. couldn’t correctly orient a card to enter a slot, but if told to put the card into the slot, she could do it successfully even though she couldn’t identify the slot orientation.

- A similar distinction exists for audio. Auditory object recognition probably involves several distinct processing systems as these different systems can go wrong without affecting other systems.

- E.g. Patient C.N. with amusia, the inability to perceive music.

- The “where” system appears to be essential for more than just determining the locations of different objects, it’s also critical for guiding interactions with these objects.

- E.g. Patient J.S. displayed a similar condition to patient D.F. where he couldn’t recognize objects. However, he could vary his grasp and hand shape to pick them up, suggesting that his brain does perceive the detail and orientation of objects.

- Patients D.F. and J.S. offer examples of single dissociations where they are able to act on objects but can’t recognize them. Optic ataxia is the reverse dissociation.

- Optic ataxia: a condition where patients can recognize objects but can’t use visual information to guide their actions.

- E.g. Patients can identify objects but they grasp for it as if they are blind.

- Visual agnosia appears with damage to the ventral/what/temporal visual stream and optic ataxia appears with damage to the dorsal/where/parietal visual stream.

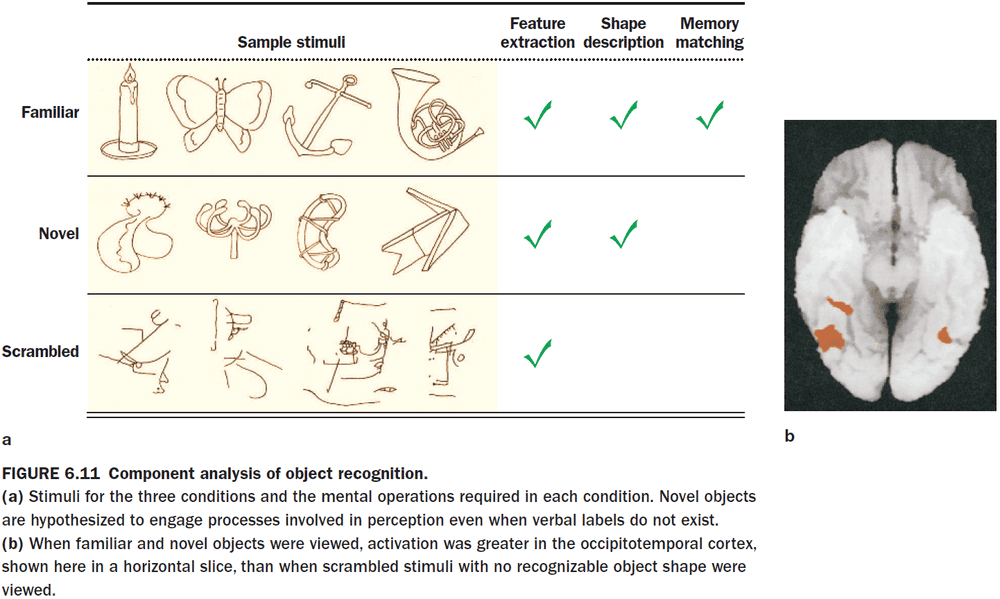

- Object perception depends primarily on the analysis of the shape of a visual stimulus.

- While color, texture, and motion can help, shape is the primary method for object perception.

- How does the brain encode shape?

- This question emphasizes the idea that perception involves connecting sensation and memory since we need to match the current sensation to our knowledge of object shape.

- When presented novel and familiar stimuli, the lateral occipital cortex (LOC) increases in blood flow suggesting that it’s the location for storing information about objects.

- Interestingly, it seems that recognizing something familiar from something unfamiliar requires the same amount of processing.

- Multistable perception: when competing stimuli are present and the brain stabilizes on one perception or interpretation.

- E.g. Necker cube illusion or vase-face illusion.

- To explain multistable perception, it’s theorized that competition in the early stages of visual processing coalesces into a stable percept by the time it reaches the inferior temporal lobe.

- Theory behind object recognition

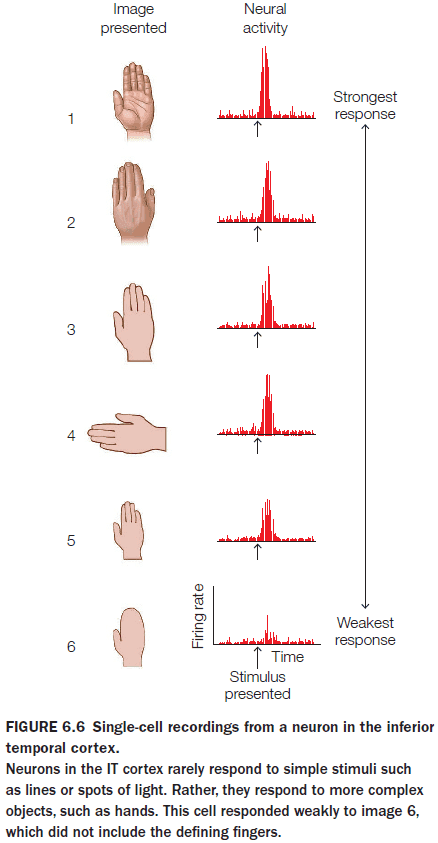

- Cells in the IT cortex selectively respond to complex stimuli, consistent with hierarchical theories of object perception.

- Initial areas of the visual cortex code basic features such as line orientation and color.

- The output of these areas is combined to form more complex feature detectors.

- Each successive stage codes more complex combinations.

- Grandmother-cell hypothesis

- There are specific cells for recognizing objects and people such as your grandmother.

- Evidence comes from epilepsy patients who had cells that only responded when the patient views a specific person.

- However, the study is questionable as the name of the person also activated the cell.

- So maybe the cell doesn’t represent viewing the person but instead represents the general concept of the person or the name of the person.

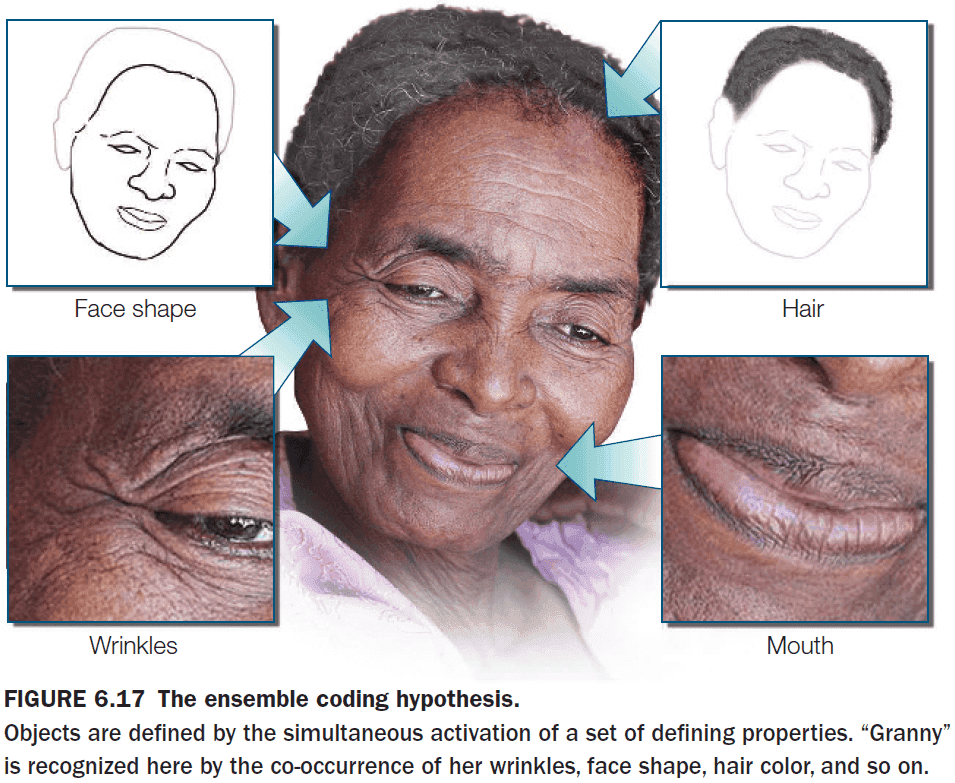

- An alternative to the grandmother-cell hypothesis is the ensemble hypothesis; that an ensemble of cells is activated for object recognition.

- Recognition isn’t due to one unit but to the collective activation of many units.

- Ensemble theories account for why we can recognize similarities between objects as only part of the ensemble activates.

- They also account for why we can recognize new objects without needing more neurons, unlike the grandmother-cell hypothesis. The ensemble activates units that represent its features.

- Another strength of the ensemble hypothesis is that it’s robust to losing neurons as losing one neuron doesn’t mean that you can’t recognize an object anymore.

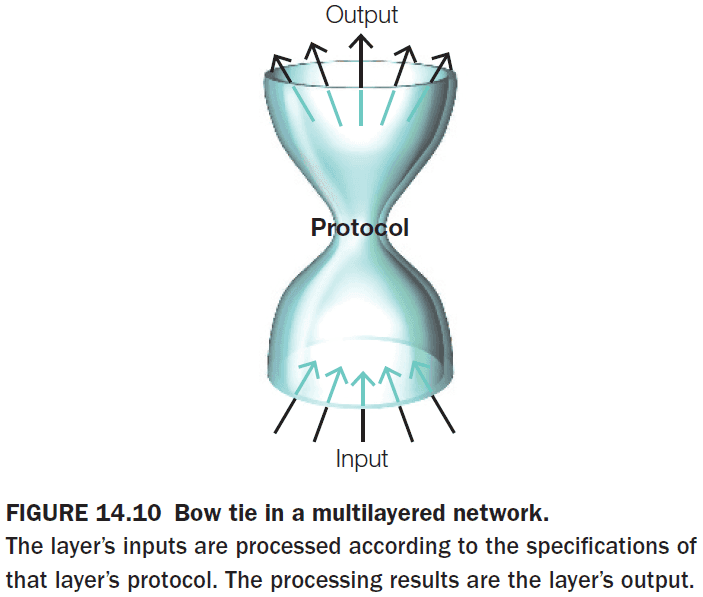

- Review of neural networks and an introduction to mind reading (brain encoding and decoding).

- We’re able to read fMRI data and decode a crude image of what the person is seeing or imagining.

- It’s possible to predict what a participant is thinking about even in the absence of any sensory input.

- Being able to read minds would help us understand the nature of dreams.

- When we meet someone, we always first look at the person’s face. No culture is an exception.

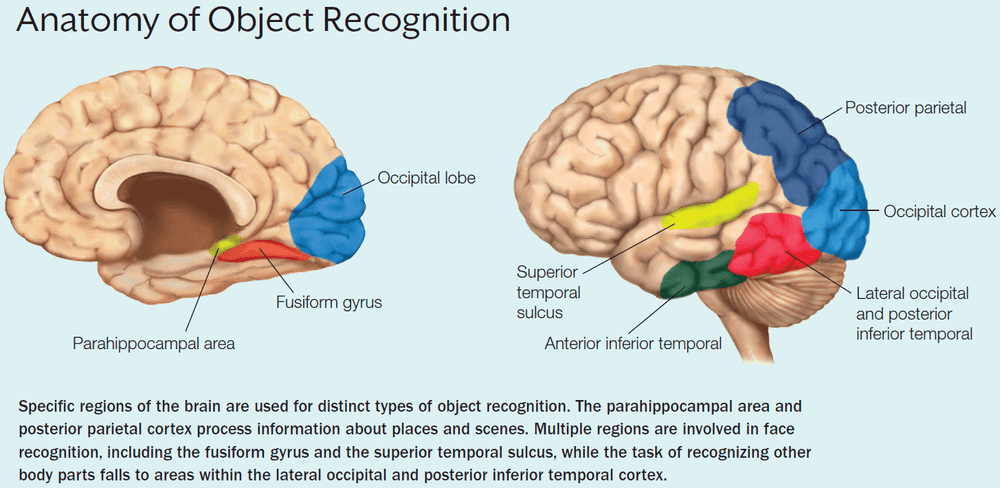

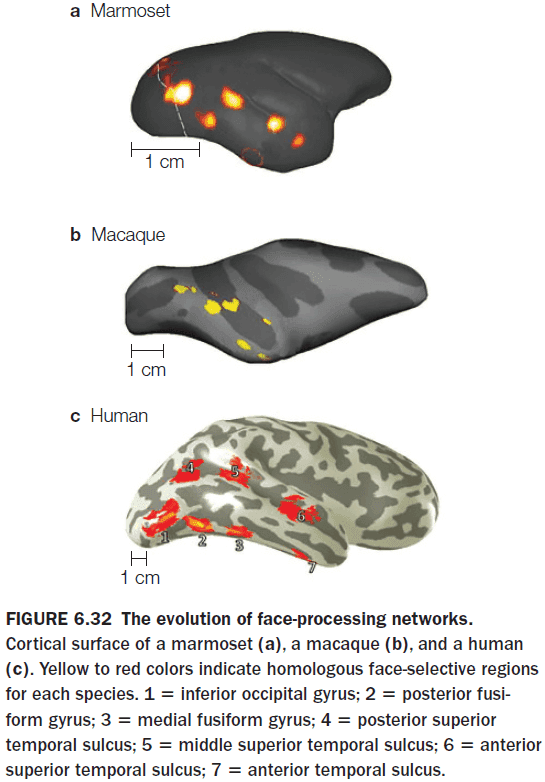

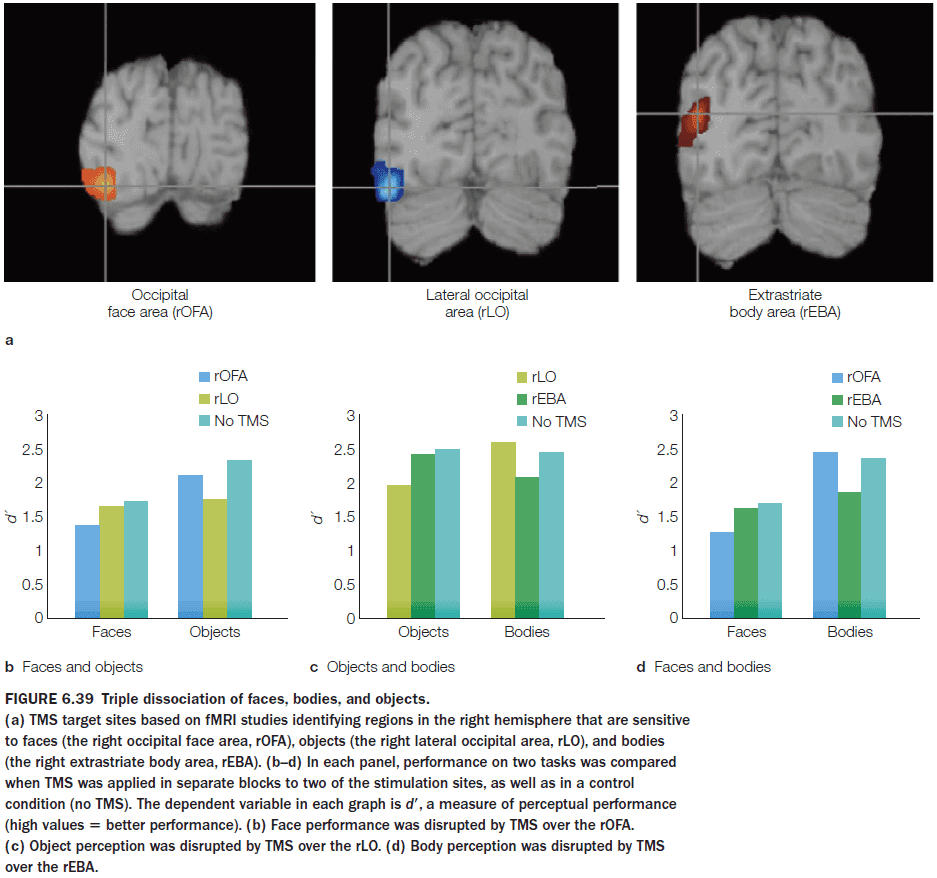

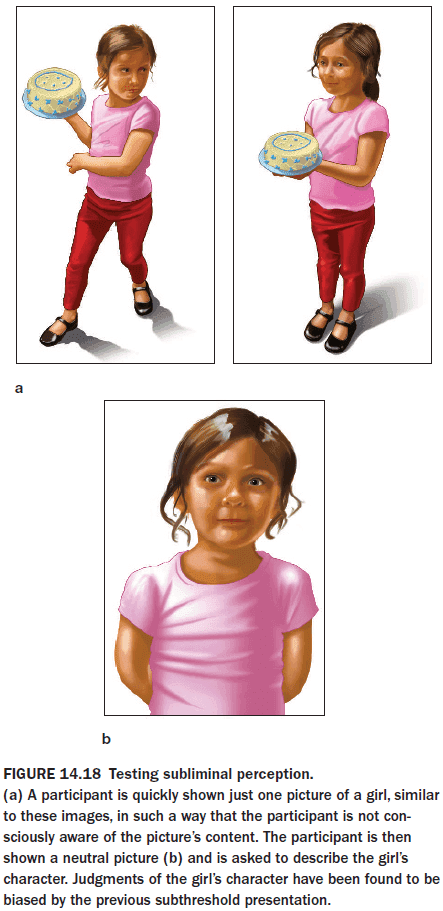

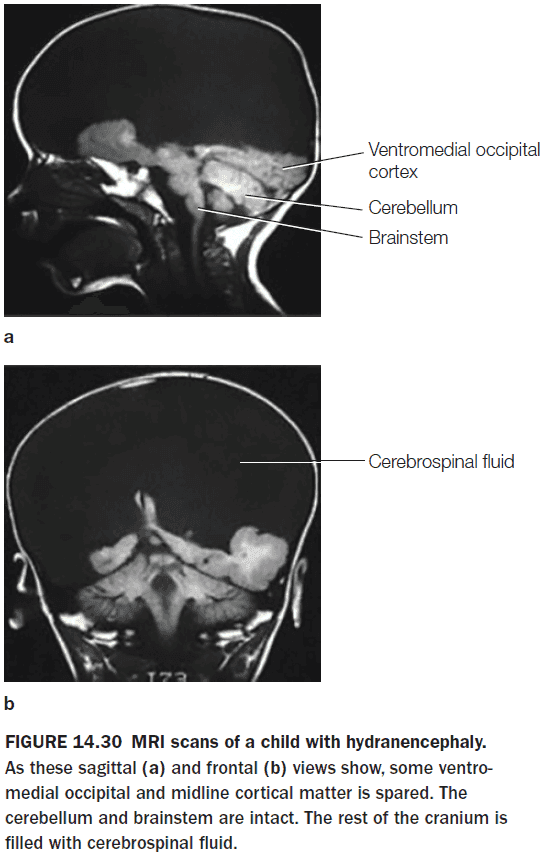

- Multiple studies argue that face perception doesn’t use the same general processing mechanisms as those used in object recognition, but instead depends on a specialized network of brain regions.

- The most prominent region for face recognition is the fusiform gyrus or the fusiform face area but this isn’t the only region that shows a strong BOLD response to faces.

- Other regions of the temporal lobe, including the superior temporal sulcus, are part of the face recognition network.

- The more ventral face pathways is sensitive to static, invariant facial features while the more dorsal pathways are sensitive to face movement.

- Are there other specialized systems for vision?

- Another system appears to be the parahippocampal place area that’s specialized for landscape images.

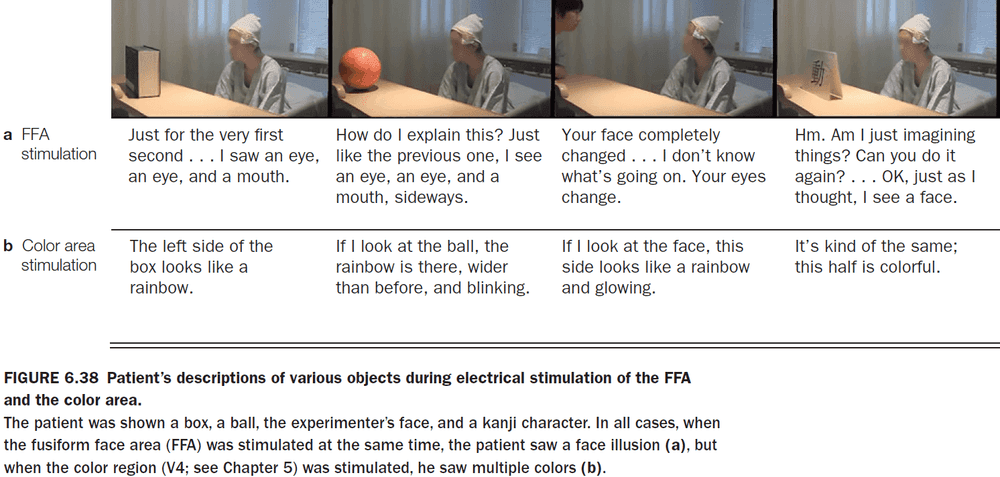

- To test the reverse dissociation for the fusiform face area, the area was stimulated in monkeys and epileptic patients.

- When the area was stimulated, monkeys performed poorly on a face-matching task and the human patients reported faces as being morphed.

- E.g. The doctor’s face morphed into someone else’s face.

- Three major subtypes of visual agnosia

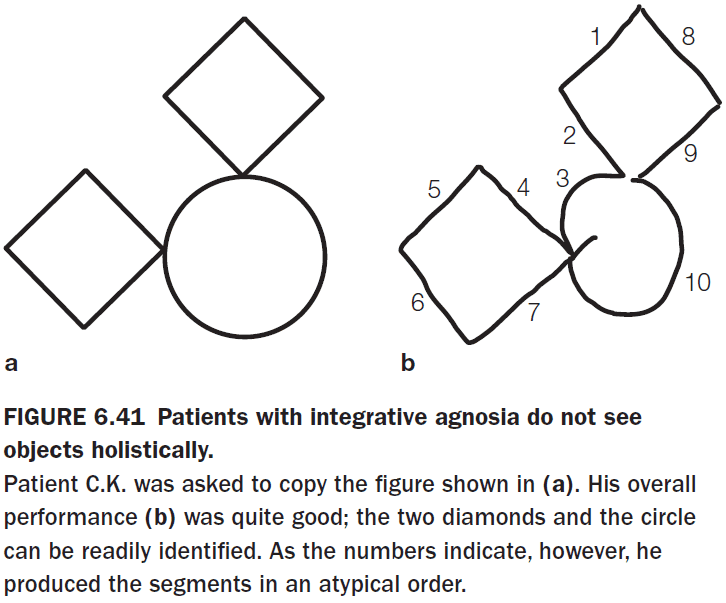

- Apperceptive: inability to recognize objects.

- Integrative: inability to integrate parts of an object into a coherent whole.

- Associative: inability to access conceptual knowledge from visual input.

- There are unusual cases of patients that exhibit object recognition deficits that are selective for specific categories.

- E.g. Problems identifying living objects even though nonliving object recognition works.

- There are two theories for why there are selective impairments of specific categories.

- Sensory/functional hypothesis: the idea that conceptual knowledge is organized around representations of sensory properties and motor properties associated with an object.

- This may explain why there is a living/nonliving perceptual divide. Nonliving objects are manipulable unlike living objects.

- Domain-specific hypothesis: the idea that conceptual knowledge is organized around categories that are evolutionarily relevant to survival and reproduction.

- By this hypothesis, dedicated neural systems evolved because they enhanced survival by more efficiently processing specific categories of objects.

- Sensory/functional hypothesis: the idea that conceptual knowledge is organized around representations of sensory properties and motor properties associated with an object.

- Tests with blind patients show that visual experience isn’t necessary for category specificity to develop within the ventral stream.

- Prosopagnosia: inability to recognize faces.

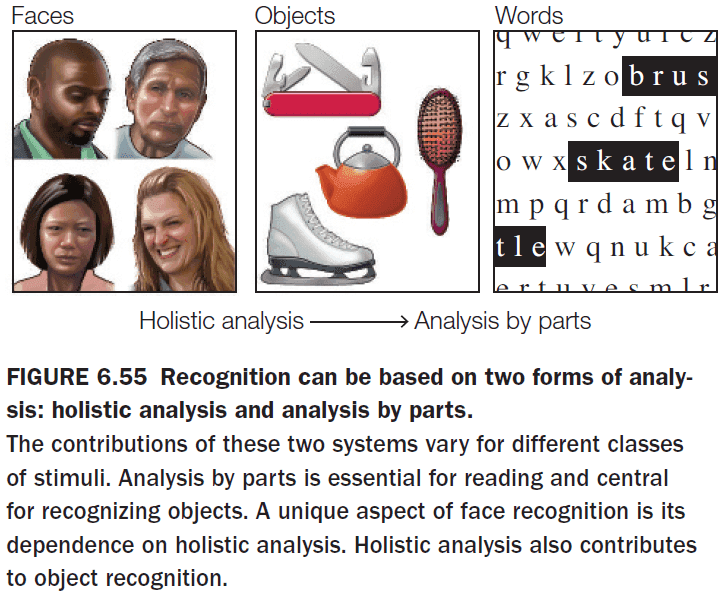

- Face perception appears to be unique in that it uses holistic processing. We recognize a person by the entire facial configuration and not by their specific facial features such as their nose, eyes, or chin.

- Holistic processing: a form of perceptual analysis that emphasizes the overall shape of an object.

- Analysis-by-parts processing: a form of perceptual analysis that emphasizes the component parts of an object.

- Words represent the other special class of objects at the other extreme and objects lie in the middle.

- Given this theory, we shouldn’t expect to find any cases where both face perception and reading are impaired but object perception remains intact. Indeed, we don’t find any cases.

Chapter 7: Attention

- Big questions

- Does attention affect perception?

- To what extent does our conscious visual experience capture what we perceive?

- What neural mechanisms are involved in the control of attention?

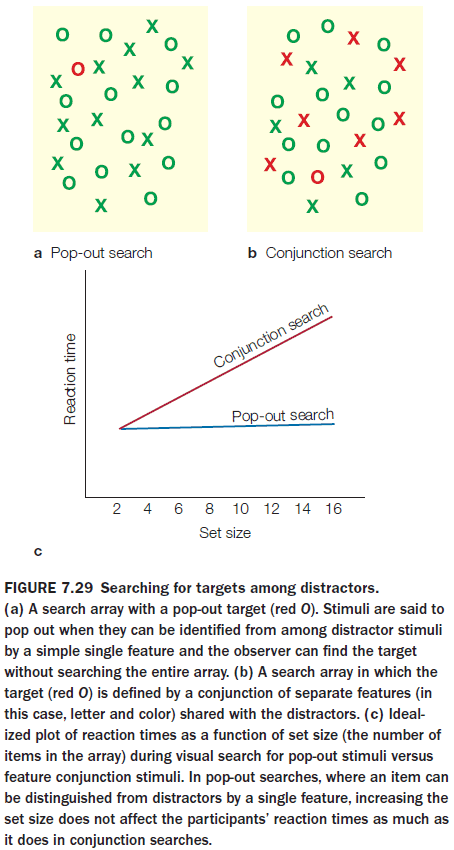

- The central problem of attention is how the brain is able to select some information at the expense of other information.

- We can choose the focus of attention; that is, it can be voluntary.

- We are also only able to attend to one thing at a time, not many things.

- First we distinguish attention from arousal.

- Arousal: the global physiological and psychological state of the organism.

- E.g. Deep sleep to hyperalertness.

- Selective attention: the allocation of attention among relevant inputs, thoughts, and actions, while ignoring irrelevant or distracting ones.

- E.g. Choosing to focus on reading this sentence instead of reading Twitter.

- What determines the priority?

- Goal-driven control (top-down): voluntary attention steered by an individual’s current goals.

- E.g. Focusing on doing homework for a class instead of partying.

- Stimulus-driven control (bottom-up): reflexive attention steered by a stimulus.

- E.g. Hearing a loud bang while studying.

- Goal-driven control (top-down): voluntary attention steered by an individual’s current goals.

- There are also two types of selective attention

- Overt: a physical shift in attention.

- E.g. Moving your eyes.

- Covert: a mental shift in attention.

- E.g. Looking straight on but focusing on what’s happening in the periphery. Eavesdropping. The spotlight of attention.

- Overt: a physical shift in attention.

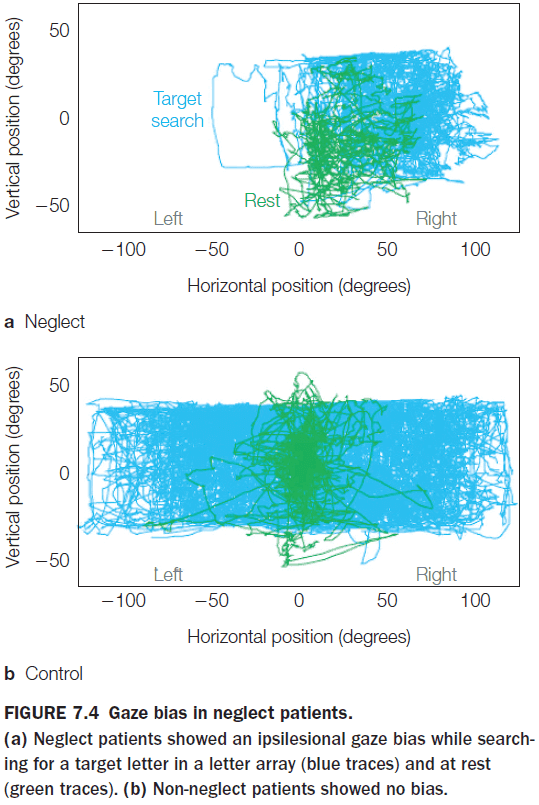

- Unilateral spatial neglect (USN): a condition where patients ignore half of their visual field.

- USN can also affect the imagination and memory.

- Patients with USN that try to recollect their memory of certain places neglect the side contralateral to the side with cortical damage.

- This shows that USN can’t be attributed to a failure of memory, but rather that attention to parts of the recalled images was biased.

- Patients with USN aren’t blind to the visual field as they can still detect stimuli presented in isolation in the visual field.

- But when multiple stimuli are present, USN shows up resulting in extinction.

- Extinction: the neglect of a stimulus in the presence of a competing stimulus.

- USN can be overcome if the patient’s attention is directed to the neglected location of items. This is one reason why the condition is described as a bias rather than a loss of ability to focus attention.

- One patient with USN describes it more as the inability to concentrate rather than as neglecting the stimulus.

- Three main characteristics of Balint’s syndrome

- Simultanagnosia: a difficulty in perceiving the visual field as a whole.

- Ocular apraxia: a deficit in making eye movements to scan the visual field.

- Optic ataxia: a problem in making visually guided hand movements.

- USN is the result of unilateral lesions of the parietal, posterior temporal, and frontal cortex or damage in subcortical areas.

- Balint’s syndrome is the result of bilateral occipitoparietal lesions.

- The phenomenon of extinction in neglect patients suggests that sensory inputs are competitive.

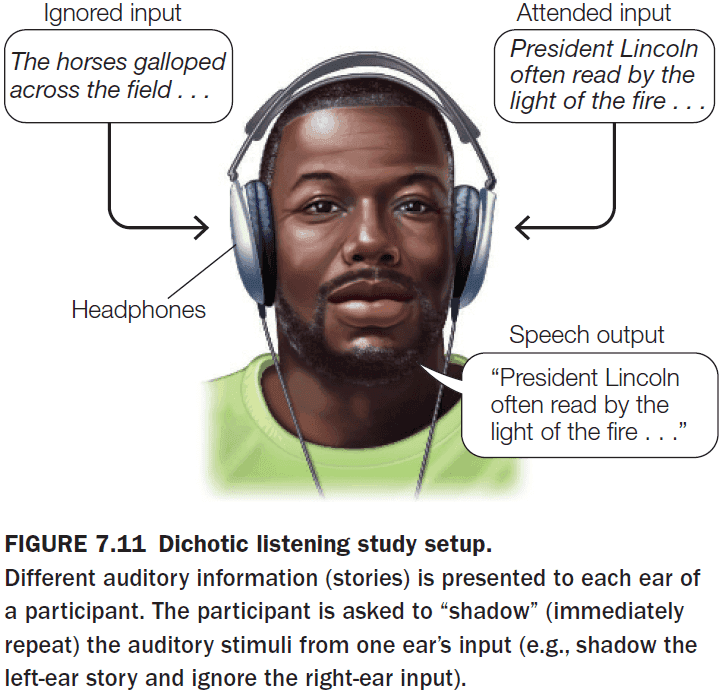

- Review of the cocktail party effect (CPE).

- Using the dichotic listening task, participants couldn’t report what the other ear heard if they focused on only hearing from one side.

- E.g. A friend whispering to you during class will make you miss what the teacher just said.

- This shows that attention affects what’s processed by the brain.

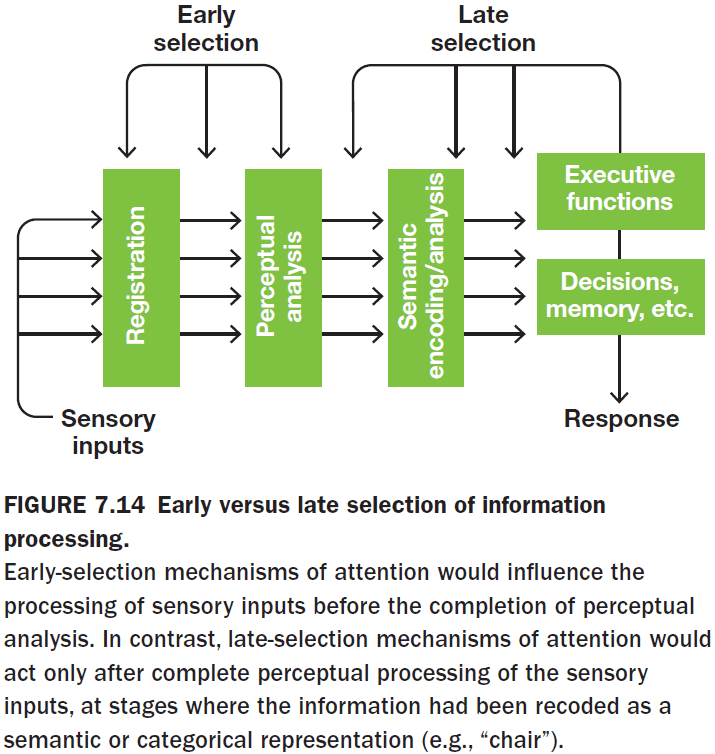

- But at what stage in the processing of sensory input does attention affect information? Does attention select in the early or late stages of processing?

- Early selection: a stimulus can be selected for before perceptual analysis is complete.

- Late selection: all stimuli are processed equally and then selection takes place at higher stages of information processing.

- However, the original all-or-none early-selection models couldn’t explain a person attending to specific information such as the person’s own name or something very interesting because this would require having perceived the information.

- The benefit of attention is that if attention is primed with a cue, then reaction times are faster. However, if the cue is invalid, then reaction times are slower.

- Attention also prevents information overload by limiting information to only the most relevant.

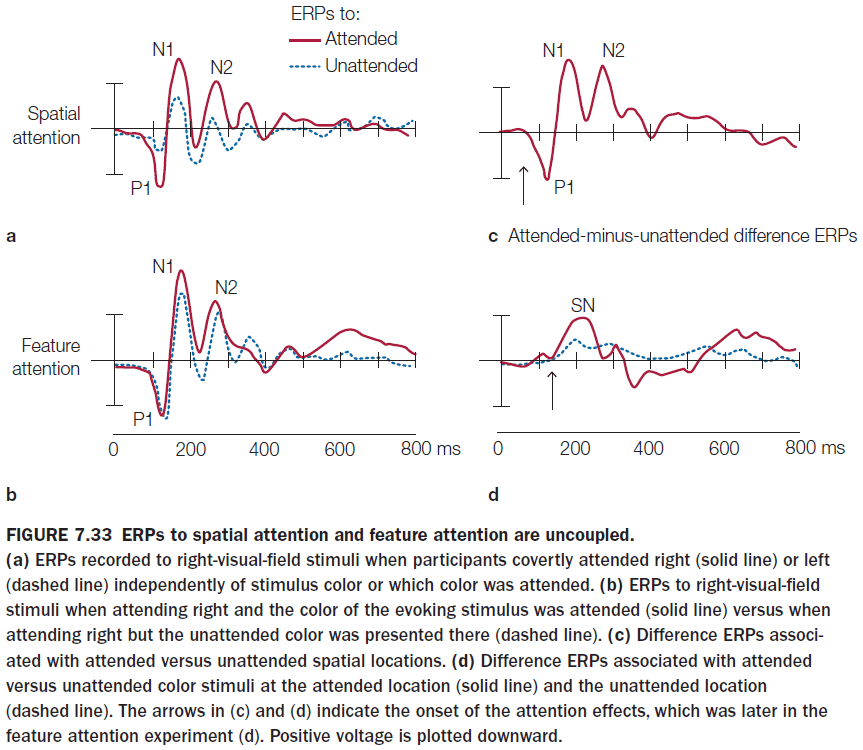

- Physiological evidence favors early selection in humans as neural signals are strongly amplified if they are attended to. This occurs before the stimulus properties can be fully analyzed.

- Selective attention operates in all sensory modalities.

- Spatial attention enhanced the responses of simple cells.

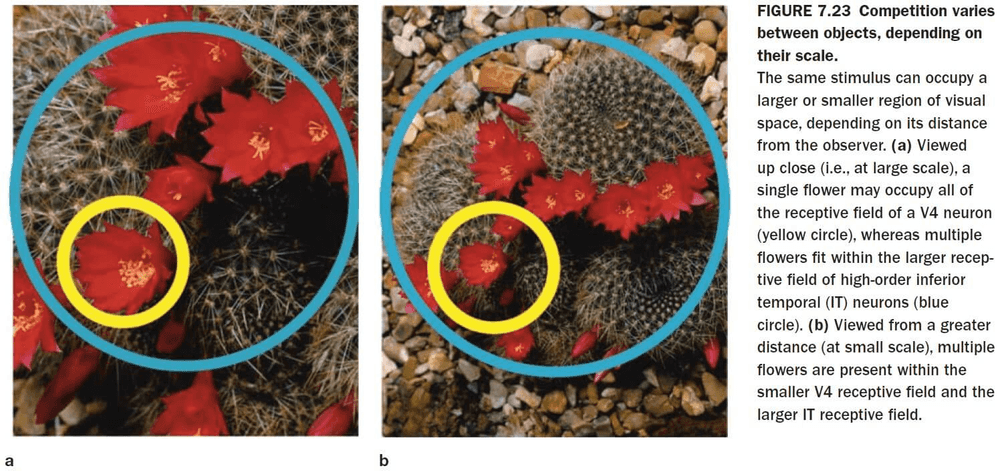

- Attention affects processing at multiple stages in the cortical visual pathways from V1 to IT cortex.

- It appears that attention attenuates the influence of the competing stimulus. It dampens distractions.

- Although attention does act at multiple levels of the visual hierarchy, it also optimizes its action to match the spatial scale of the visual task.

- Attention also works at the level of the thalamus as it’s been shown that thalamic reticular nucleus (TRN) neurons can inhibit/excite signal transmission from the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) to the visual cortex.

- Reflexive visuospatial attention can improve response times if the reflexive cue predicts the location of subsequent targets, but only for a short time after the flash (50-200 ms).

- After about 300 ms pass between the reflexive cue and the target, the effects on reaction time are reversed and participants respond more slowly.

- Inhibition of Return (IOR): inhibition of the return of attention to that location.

- Our reflexive attention has built-in IOR to prevent ourselves from locking on to distractions and if the stimulus is important and salient, we can invoke our voluntary attention to override IOR.

- Attention can be directed both to spatial locations and to nonspatial features of the target stimuli.

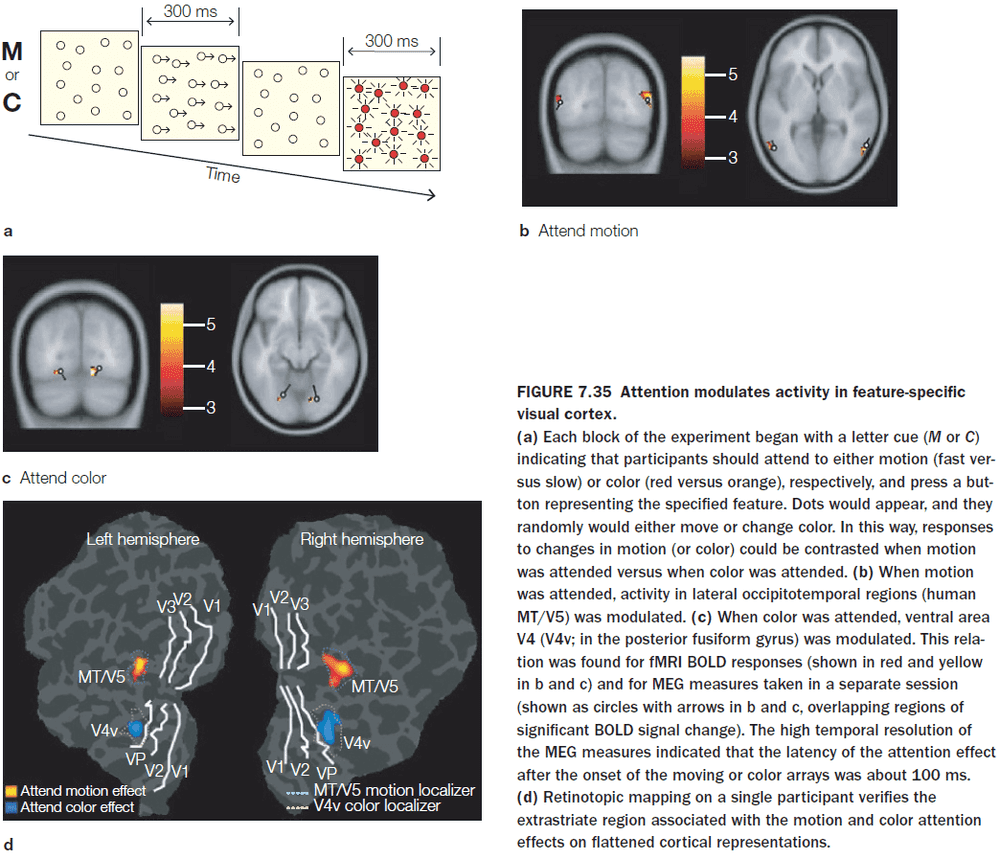

- One experiment showed that both spatial attention and feature attention can produce selective processing of visual stimuli, and that their mechanisms differ.

- Feature-based selective attention acts at relatively early stages of visual cortical processing and with relatively short latencies after stimulus onset.

- Spatial attention, however, still beats feature-based selective attention and it has an earlier effect.

- Objects influence the way spatial attention is allocated in space in that attention spreads to capture the object.

- When spatial attention isn’t involved, object representations can be the level of perceptual analysis affected by goal-directed attentional control.

- Attended stimuli produce greater neural responses than ignored stimuli and this occurs in multiple visual cortical areas.

- Studies suggest that attention alters the effective connectivity between neurons by altering the pattern of rhythmic synchronization between areas.

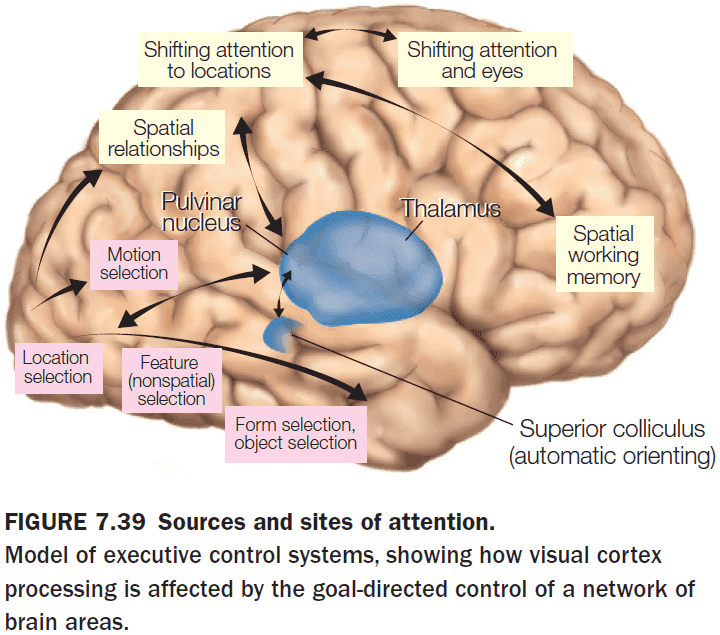

- How does goal-directed attention work?

- Top-down neuronal projects from attentional control systems contact neurons in sensory-specific cortical areas to alter their excitability.

- This results in the response in the sensory areas to a stimulus to be enhanced if the stimulus is given a high priority, or it is attenuated if it’s irrelevant.

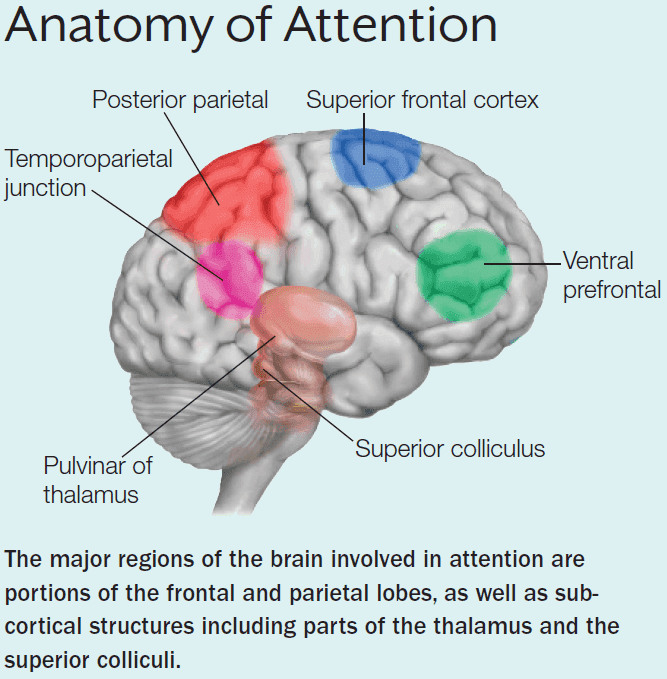

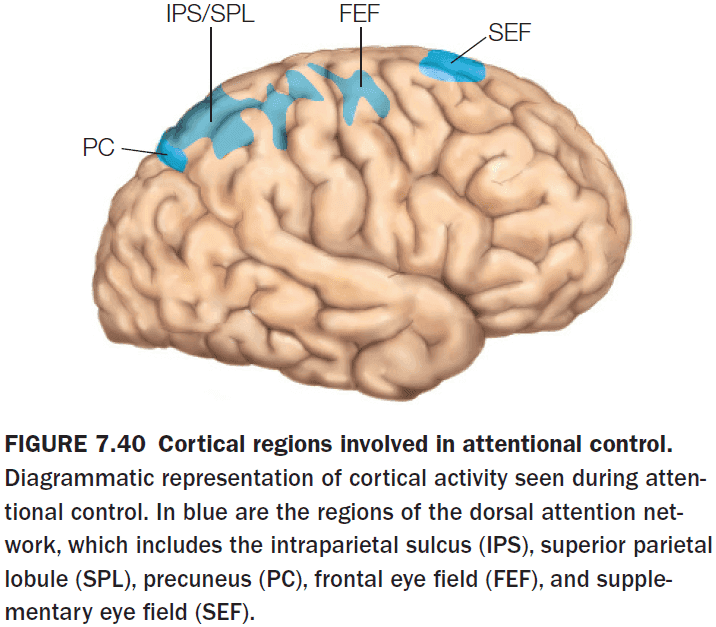

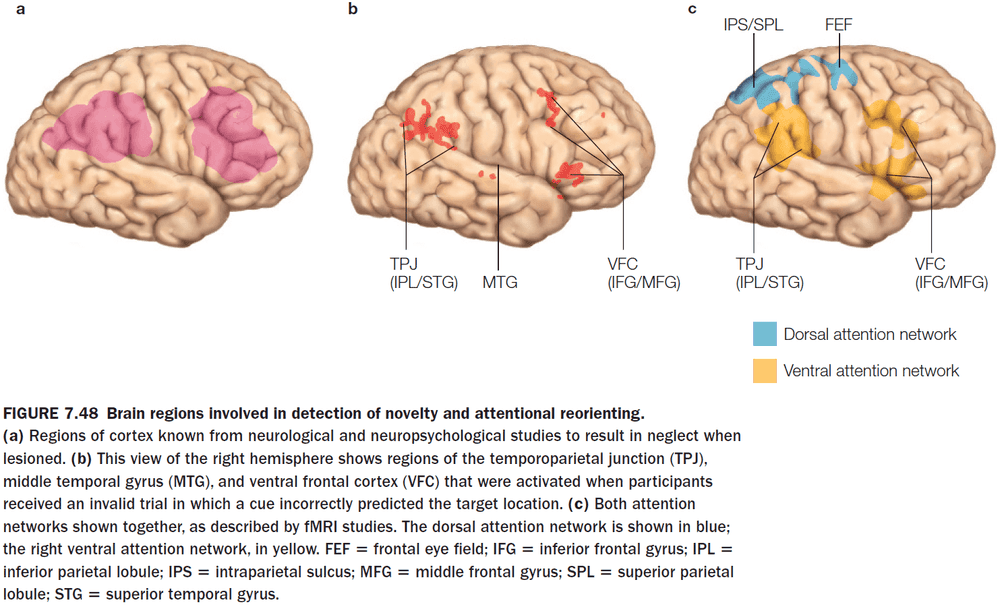

- Current models suggest two separate attention control systems

- Dorsal attention network: controls voluntary attention based on location, features, and object properties.

- Ventral attention network: controls reflexive attention stimulus novelty and salience.

- The key cortical nodes in the dorsal attention network

- Frontal eye fields (FEF)

- Supplementary eye fields (SEF)

- Intraparietal sulcus (IPS)

- Superior parietal lobule (SPL)

- Precuneus (PC)

- Impulses from the FEF coded information about the task that was about to be performed, indicating that the dorsal system is involved in generating task-specific, goal-directed attentional control signals and not a general attention signal.

- The key cortical nodes in the ventral attention network

- Strongly lateralized to the right hemisphere

- Temporoparietal junction (TPJ)

- Inferior and middle frontal gyri of the ventral frontal cortex

- Subcortical components of attentional control networks

- Superior colliculus

- Contains a topographic map of the contralateral visual hemifield.

- Strong stimulation evokes an overt eye movement.

- Weak stimulation doesn’t evoke an eye movement but it does excite the neurons.

- Weak stimulation appears to mimic the effects of covert attention.

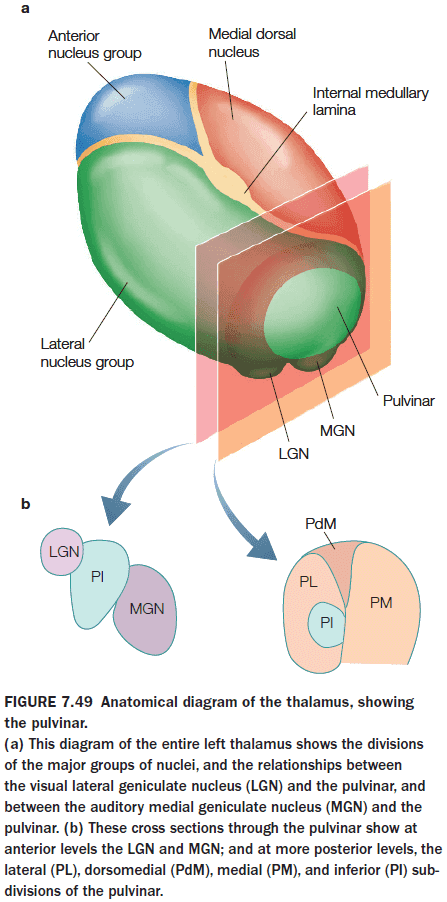

- Pulvinar of the thalamus

- Ventral-stream visual areas V1, V2, V4, and IT project topographically to the ventrolateral pulvinar (VLP), which also sends projections back to these visual areas, forming a pulvinar-cortical loop.

- May be involved in both voluntary and reflexive attention.

- The dorsomedial pulvinar appear to play a major role in covert spatial attention and in the filtering of stimuli.

- Coordinates the synchronous activity of interconnected brain regions in the ventral visual pathway.

- Superior colliculus

Chapter 8: Action

- Big questions

- How do we select, plan, and execute movements?

- What cortical and subcortical computations in the sensorimotor network support the production of coordinated movement?

- How is our understanding of the neural representations of movement being used to help people who have lost the ability to use their limbs?

- What is the relationship between the ability to produce movement and the ability to understand the motor intentions of other individuals?

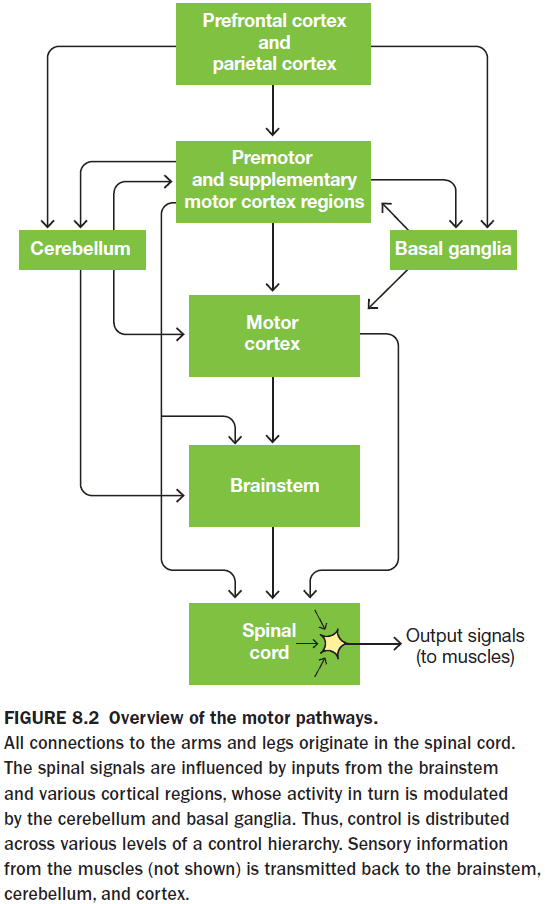

- As in perception, we can describe the motor system as a hierarchical organization with the spinal cord at the bottom and cortical regions at the top.

- Effector: a part of the body that can move.

- Review of alpha motor neurons, spinal interneurons, and reflex.

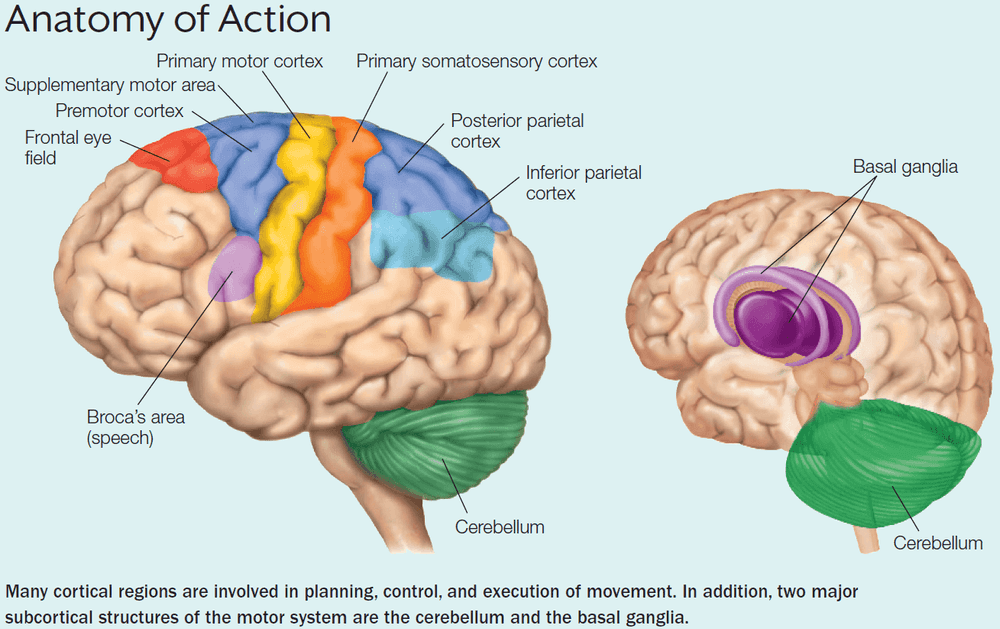

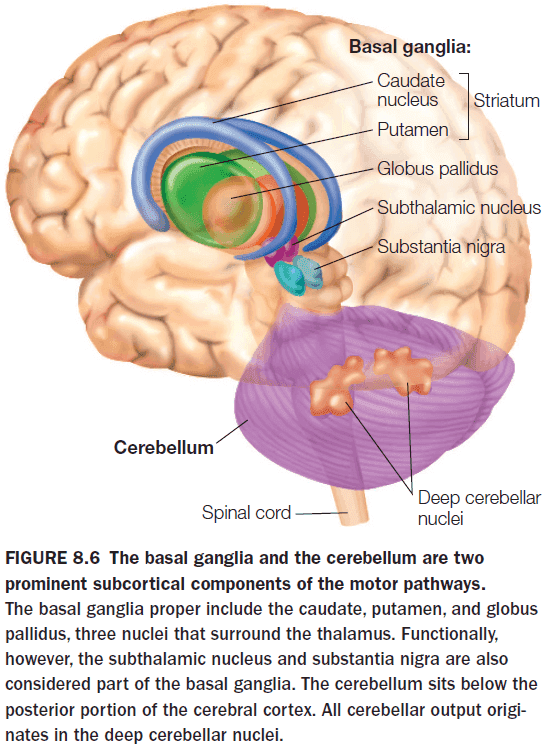

- Two subcortical structures that play a key role in motor control

- Cerebellum

- Basal Ganglia

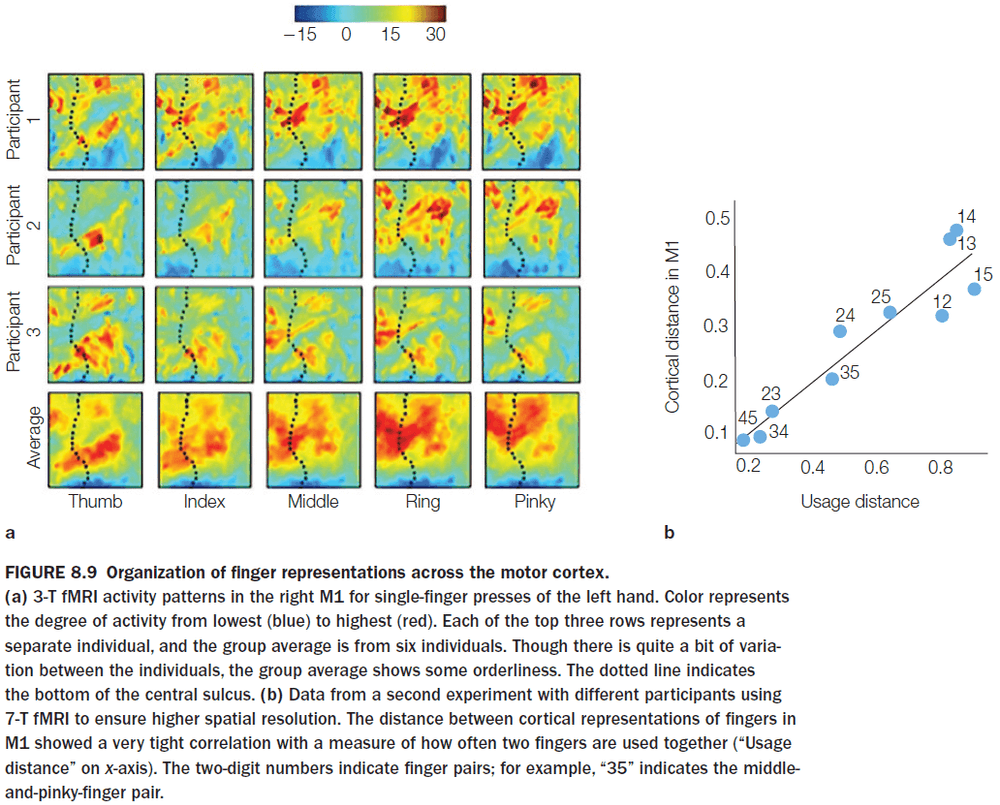

- In the primary motor cortex (M1), the representation of each effector doesn’t match its actual size, but rather the importance of that effector for movement and the level of control required for manipulating it.

- Why is a larger area needed for more precise control?

- Lesions in M1 or the corticospinal tract result in hemiplegia.

- Hemiplegia: the inability to produce voluntary movement.

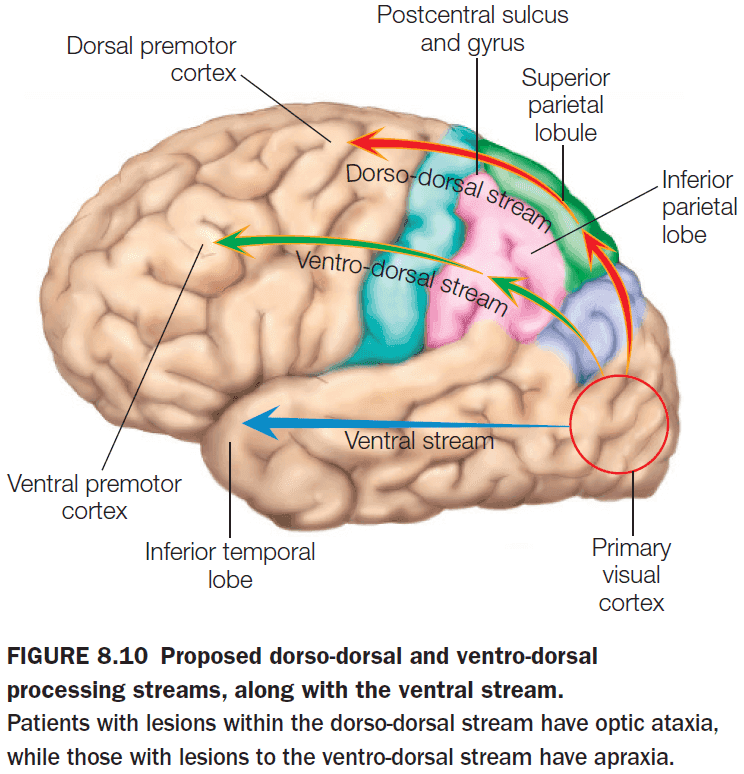

- The dorsal/where visual stream can be further subdivided into a dorso-dorsal stream and a ventro-dorsal stream.

- The dorso-dorsal stream is used for the act of reaching as it requires the representation of the location of an object in space with respect to the person’s own body.

- Damage to the dorso-dorsal stream results in optic ataxia.

- Optic ataxia: the inability to reach for objects even though they can recognize it.

- The ventro-dorsal stream is used for producing transitive gestures (manipulating an object) and intransitive gestures (signifying intension such as waving goodbye).

- Damage to the ventro-dorsal stream results in apraxia.

- Apraxia: the inability to make coordinated, goal-directed movement.

- Central pattern generator (CPG): neurons within the spinal cord that can generate an entire sequence of actions without any external feedback signal.

- The motor system is truly hierarchical because the highest levels are only concerned with issuing commands to achieve an action, whereas lower-level mechanisms translate those commands into a specific neuromuscular pattern via CPGs.

- So if cortical neurons aren’t coding specific patterns of motor commands, what are they doing?

- Two types of action plans

- Trajectory-based: specifying the current location and how to move to get to the new location.

- Location-based: specifying the new location and what’s needed at the new location.

- Experiments with monkeys favor the location-based action plan.

- This reminds me of the mouse-maze experiment in the cognitive science textbook where it showed the same result. Mice make cognitive maps based on locations, not movements.

- Location isn’t the only information being encoded though as actions require a set of sequential movements.

- These movements are guided by a hierarchy with abstract representations at the top and sequential movements at the bottom.

- Two key ideas on movement

- Motor control depends on several distributed anatomical structures.

- These distributed structures operate in a hierarchical organization.

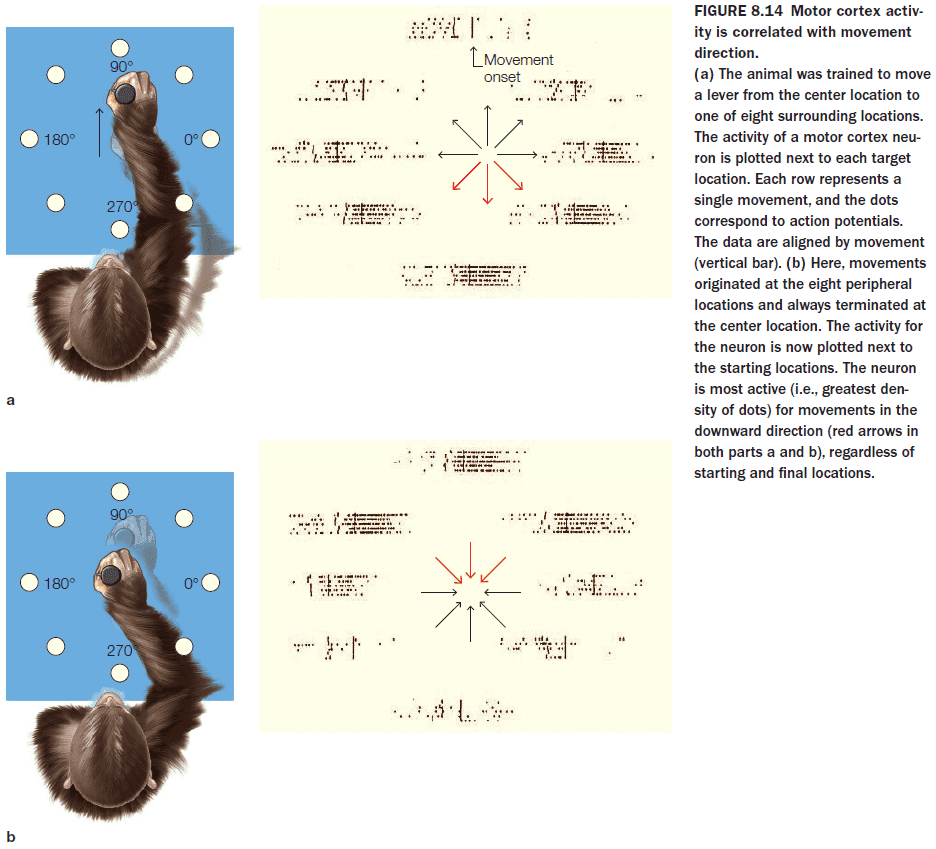

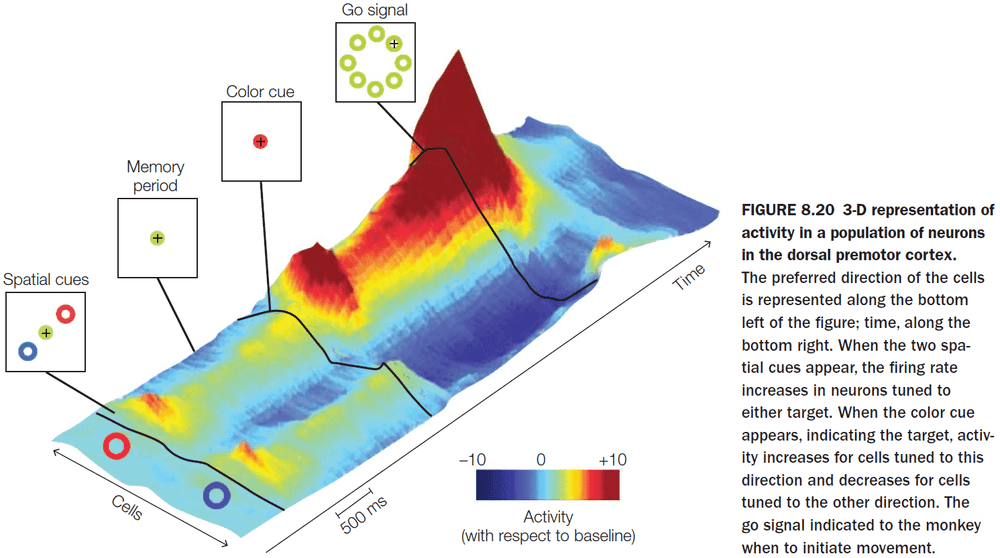

- In Georgopoulos’s experiment, the activity of cells in M1 correlates better with movement direction than with target location.

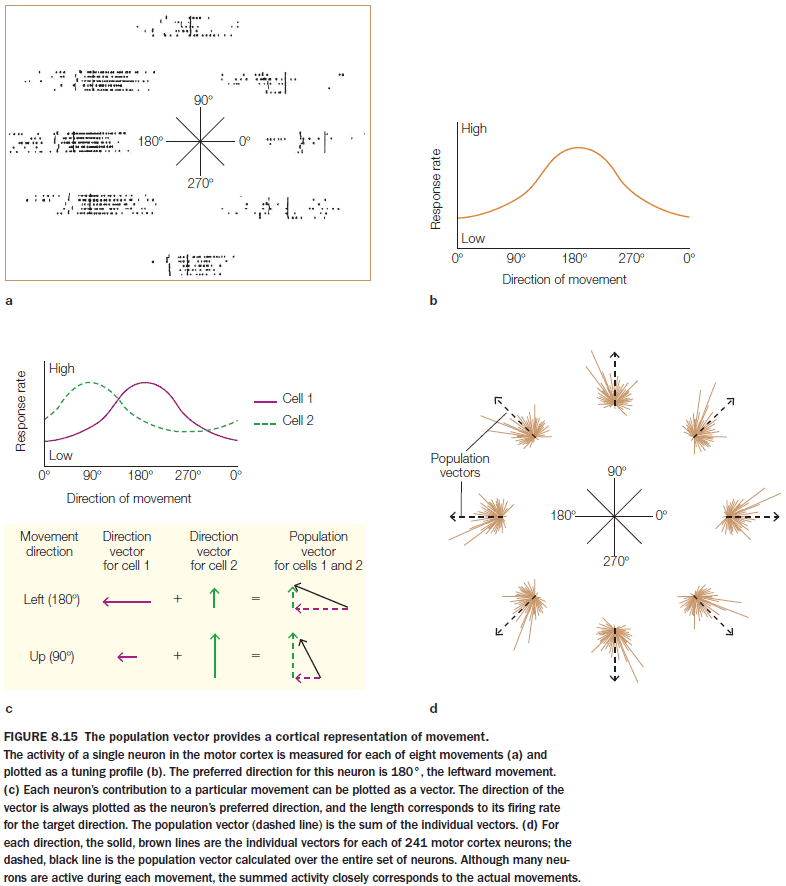

- Many cells in the motor cortex show directional tuning or a preferred direction.

- If we try to predict the direction of movement by observing only one neuron, it would be very difficult as we wouldn’t have enough information to predict the direction.

- One solution is to use a population vector.

- Population vector: combining the activity of many neuron (assuming that a neuron’s activity is stronger when the desired direction of movement more closely matches its preferred direction).

- The population vector does predict the direction of movement, however, we must keep in mind that the data is correlational and we don’t know if the cells are coding for their preferred direction or some other variable such as muscle contraction.

- There is some evidence that the population vector can predict movement before it occurs but there are some issues.

- Issues with population vectors

- Many cells don’t show strong directional tuning.

- Tuning may be inconsistent.

- There may not be a simple mapping from behavior to neural activity as neurons may wear many hats, coding different features depending on the time and context.

- An alternative to population coding is to model the activity of neurons using a dynamic model that defines the trajectory of neural activity in abstract, multidimensional space.

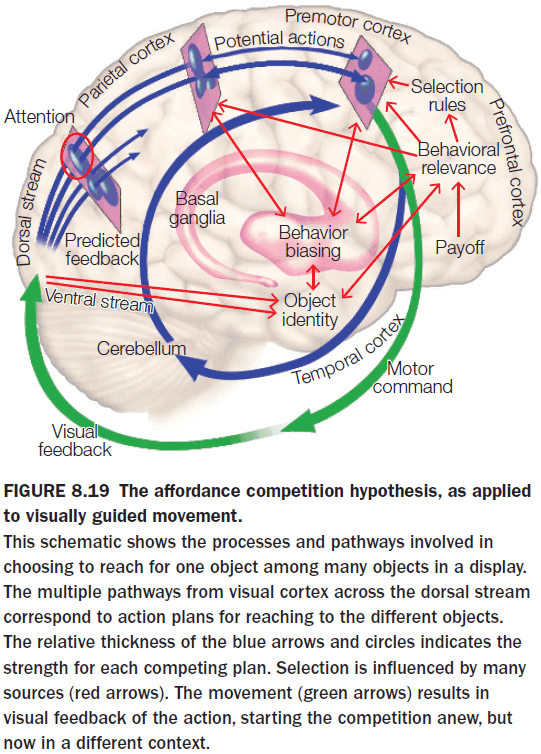

- How do we select goals and plan motor movements to achieve those goals?

- The affordance competition hypothesis (ACH) is one answer.

- ACH proposes that the processes of action selection (what to do) and implementation (how to do it) occur simultaneously within the brain and continuously evolves.

- Affordances: the opportunities for action defined by the environment.

- Starting with our ancestors, they lived in a changing and hostile environment which doesn’t allow time for carefully evaluating goals and options.

- A better strategy is to develop multiple plans in parallel.

- E.g. While we’re performing one action, we’re preparing for the next one.

- Feedback from our sensors continuously updates our affordances and how to carry them out, while our internal state, longer-range goals, and expected rewards provides information that can be used to assess the utility of the different actions.

- Eventually, one option wins and executed.

- Evidence for ACH comes from monkeys. When they are presented with two targets, neural signatures for both movements could be seen even though the monkey hadn’t been told which target to move to.

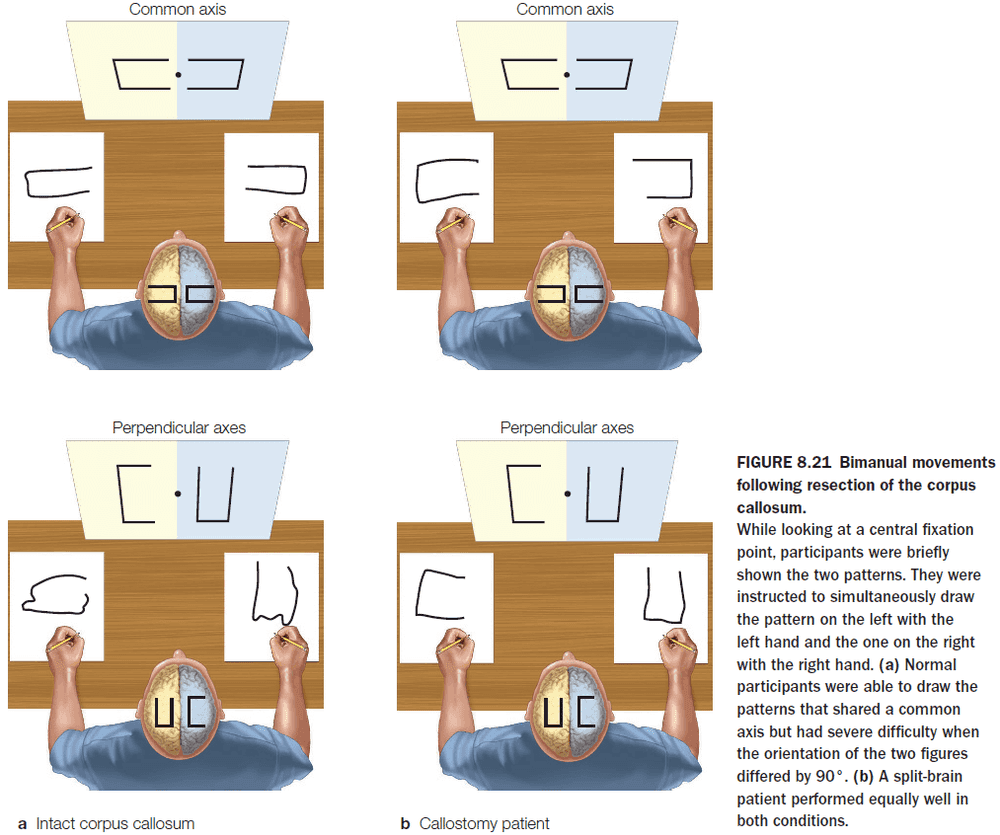

- Further evidence comes from split-brain patients where they can draw two simultaneous patterns using both hands while normal people have difficulty doing the same task.

- This reveals that motor planning involves some cross talk between the two hemispheres.

- Damage to the supplementary motor area (SMA) leads to impaired performance on tasks that require integrated use of both hands and to alien hand syndrome.

- Alien hand syndrome: a condition where one limb produces a seemingly meaningful action but the person denies responsibility for the action.

- Behaviors such as alien hand syndrome and difficulty performing multiple, parallel motor tasks, such as rubbing your stomach and patting your head, further supports the idea that motor planning is a competitive processing.

- Differences between posterior parietal cortex and premotor regions

- Parietal cortex uses an eye-centered reference frame, while premotor regions use an hand-centered reference frame.

- Parietal cortex is linked to motor intention, while premotor regions are linked to movement execution.

- Conscious awareness of movement appears to be related to the neural processing of action intention rather than the movement itself.

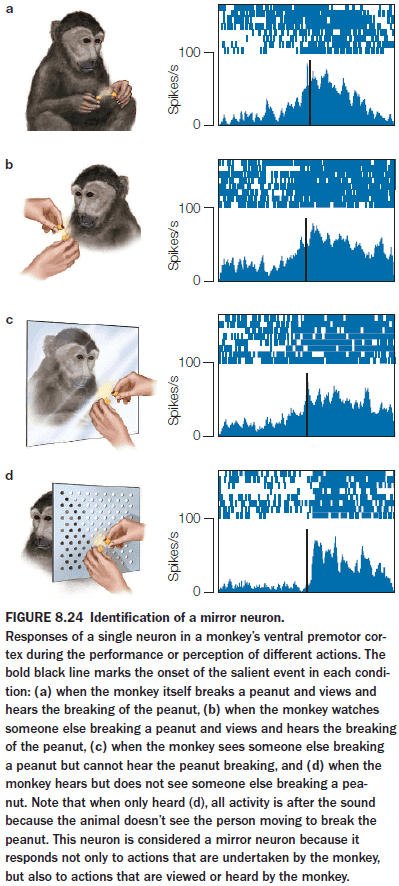

- Mirror neurons (MNs): neurons that fire both when an action is observed and when the individual performs the same action.

- The activity of MNs is correlated with a goal-oriented action and is independent of how this information is received.

- MNs intimately link perception and action, suggesting that our ability to understand the actions of others depends on the neural structures that would be engaged if we were to produce the action ourselves.

- Experiments with MNs also show that with expertise, the motor system has a fine sensitivity to discriminate good and poor performance during action observation, a form of action comprehension. This also suggests that our motor system is anticipatory in nature.

- E.g. Only the neurons in skilled basketball players showed a different response to successful and unsuccessful free throw video clips when compared to journalists and normal people.

- Dividing the brain into perception and motor regions may be useful in organizing neuroscience information, but the brain doesn’t honor such divisions.

- Review of brain-machine interfaces (BMI).

- Given multiple action plans, how do we decide which plan to execute?

- The basal ganglia (BG) plays a critical role in movement initiation and is positioned to help resolve the competition among action plans.

- The BG is unique in its use of double inhibition as it allows for making a pattern stand out against the background, thus it might be how an action plan gets decided.

- Disorders such as Huntington’s disease and Parkinson’s disease affect the BG, resulting in abnormal movements and postures.

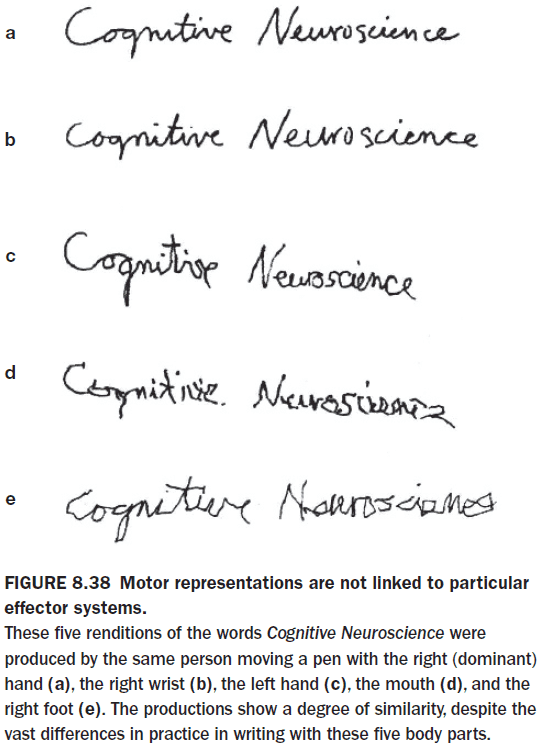

- Some aspects of motor learning are independent of the muscular system used to perform the action.

- E.g. You can write your signature using both hands, your mouth, and your feet. While the signature won’t be as clean, this shows that some muscle groups simply have more experience in translating abstract representations into a concrete action.

- The first effects of learning likely start at the abstract level rather than the concrete level.

- Gradually, the motor system learns to execute the movement in what feels like an automatic manner, requiring little conscious thought.

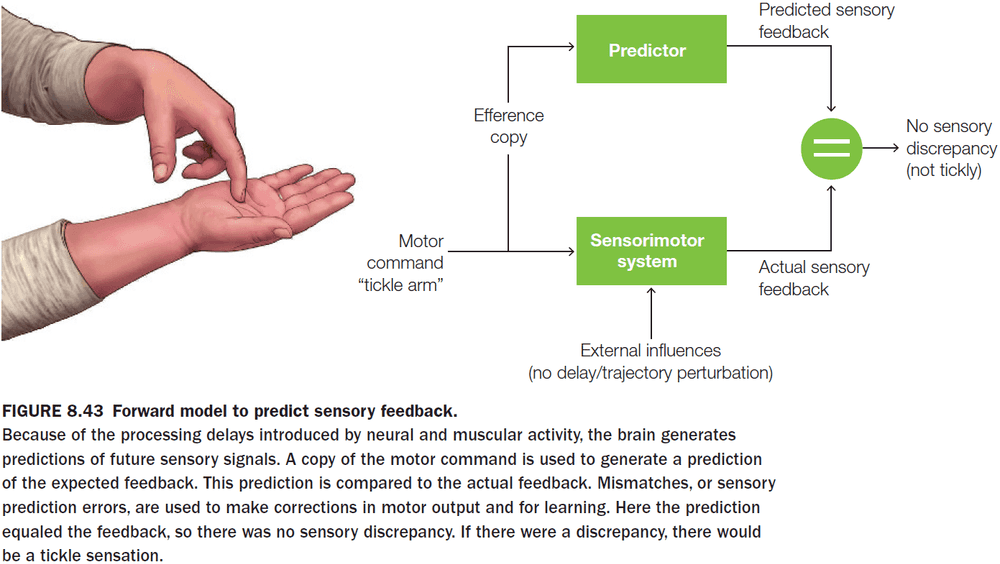

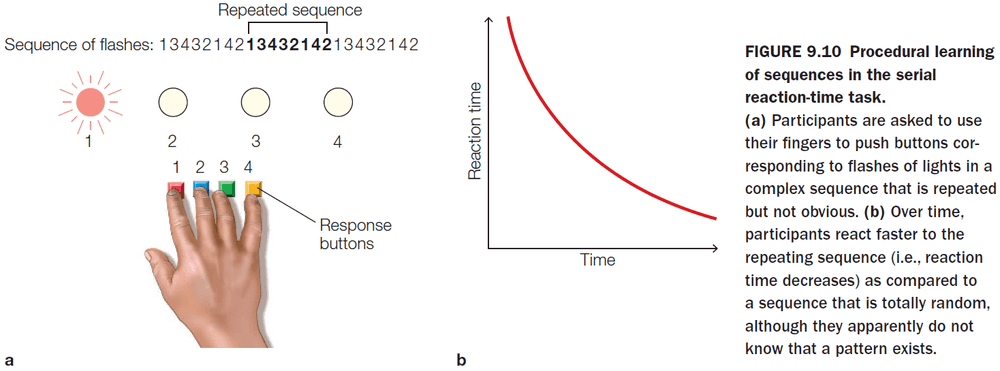

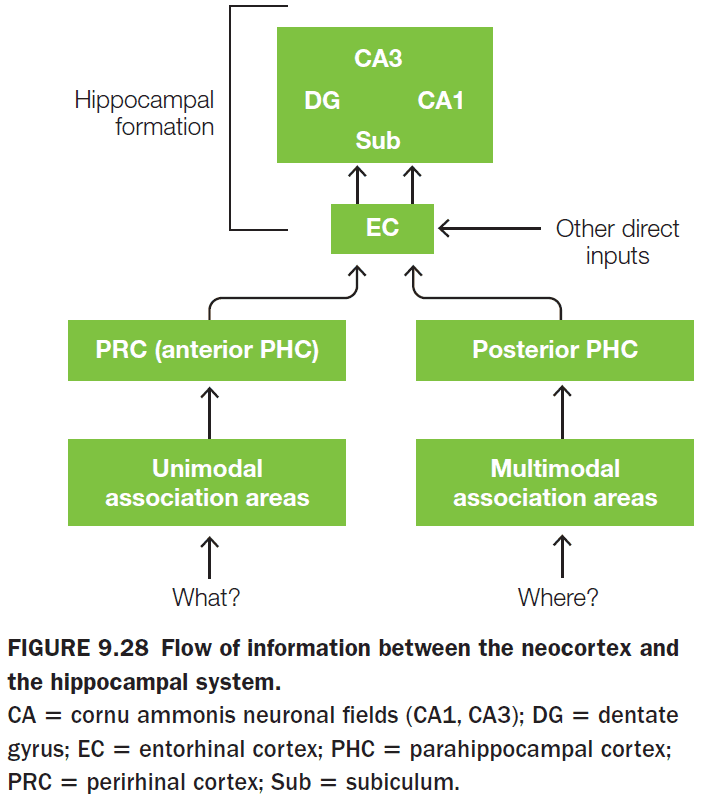

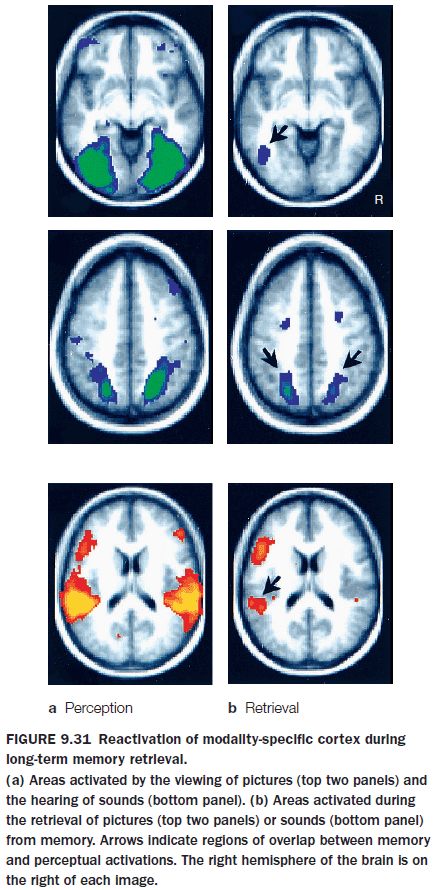

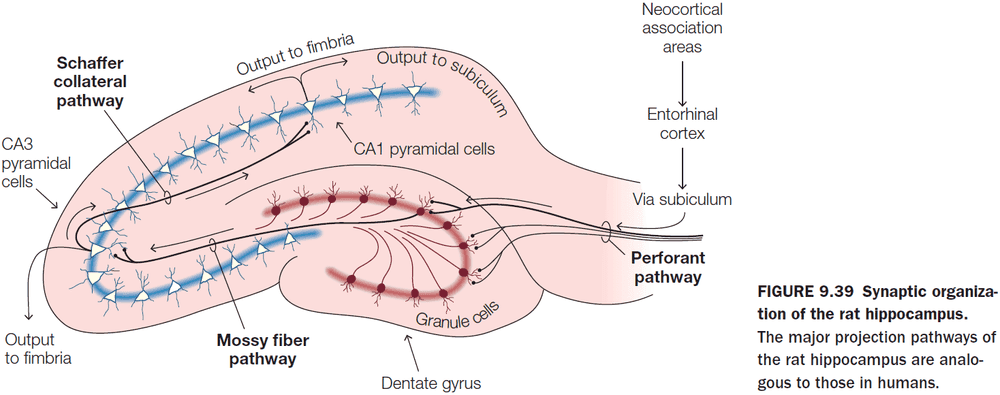

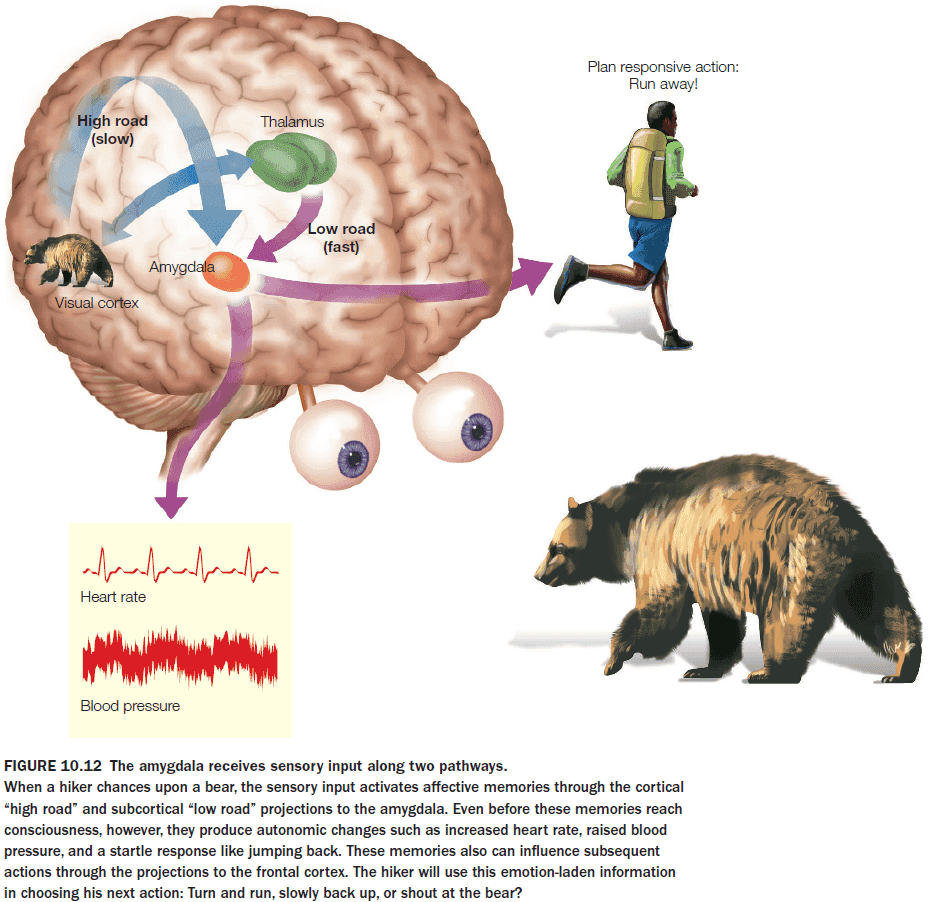

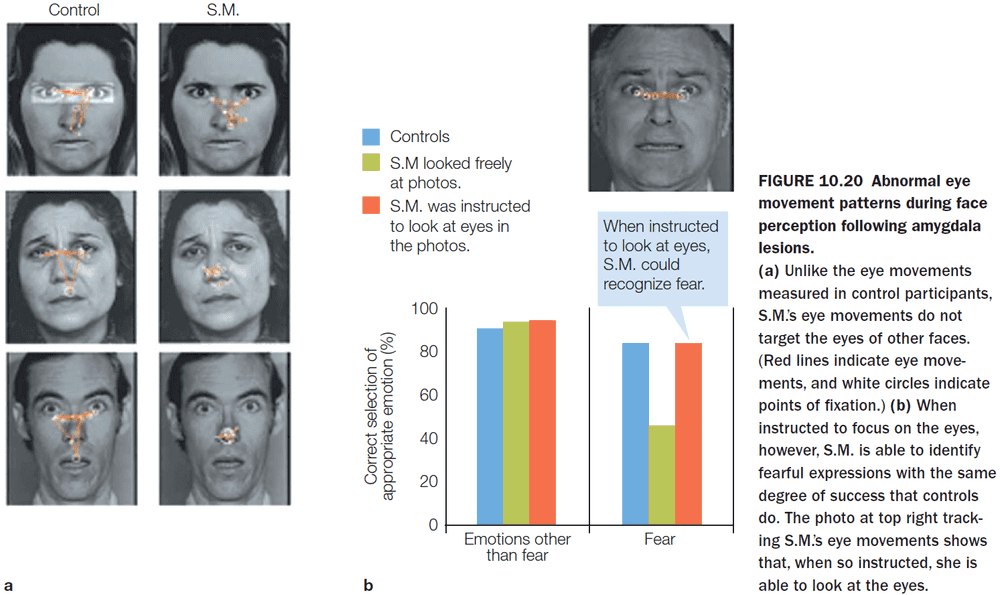

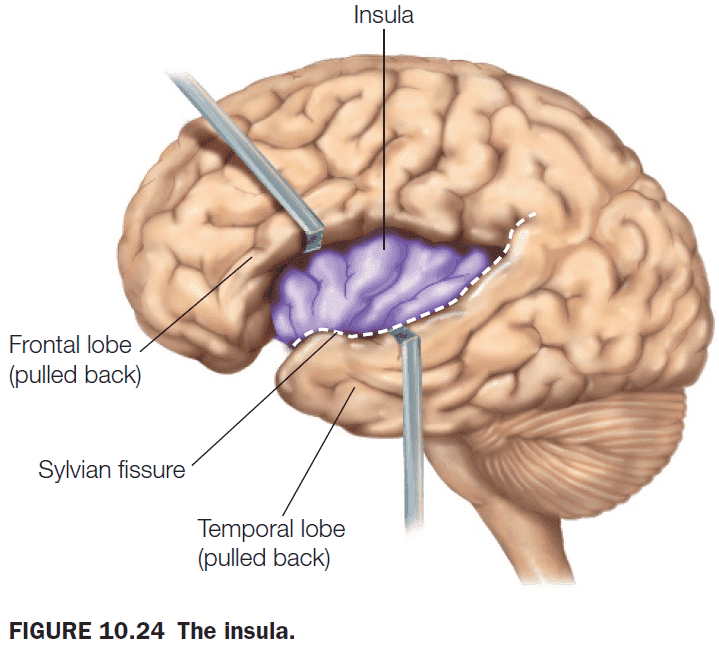

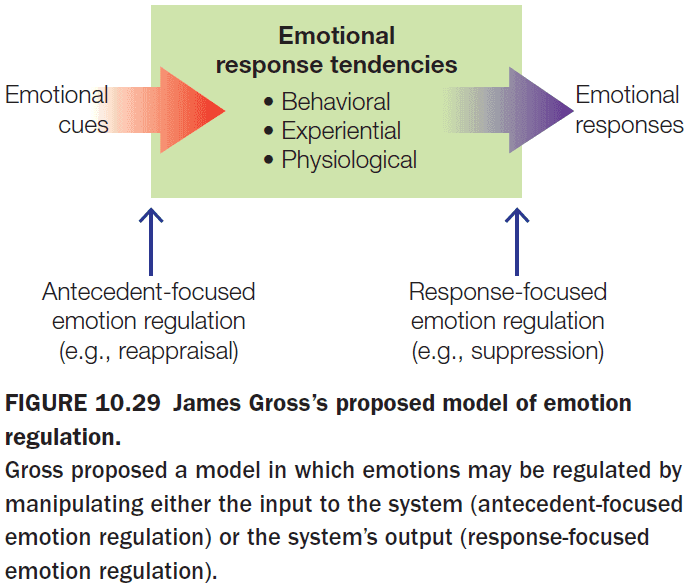

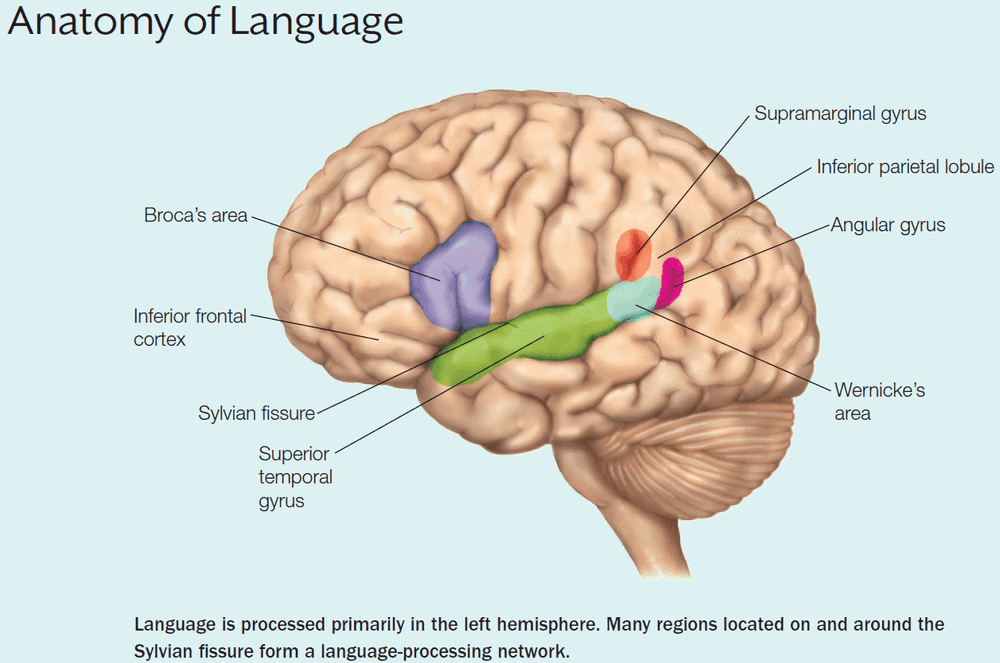

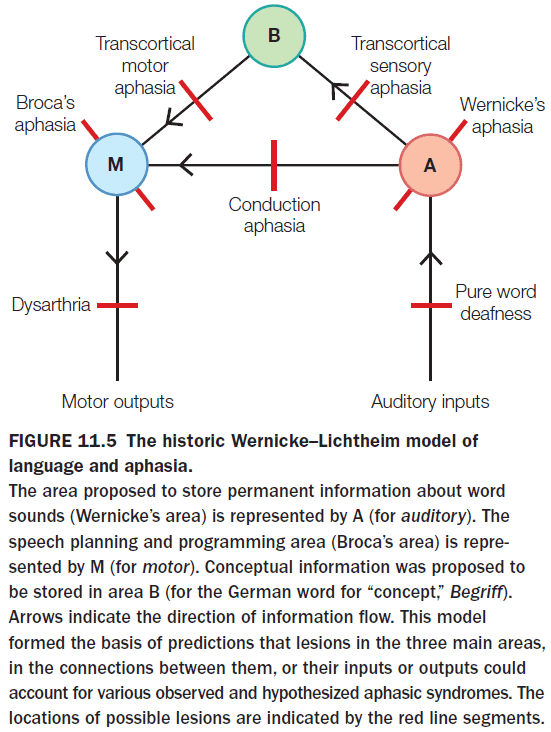

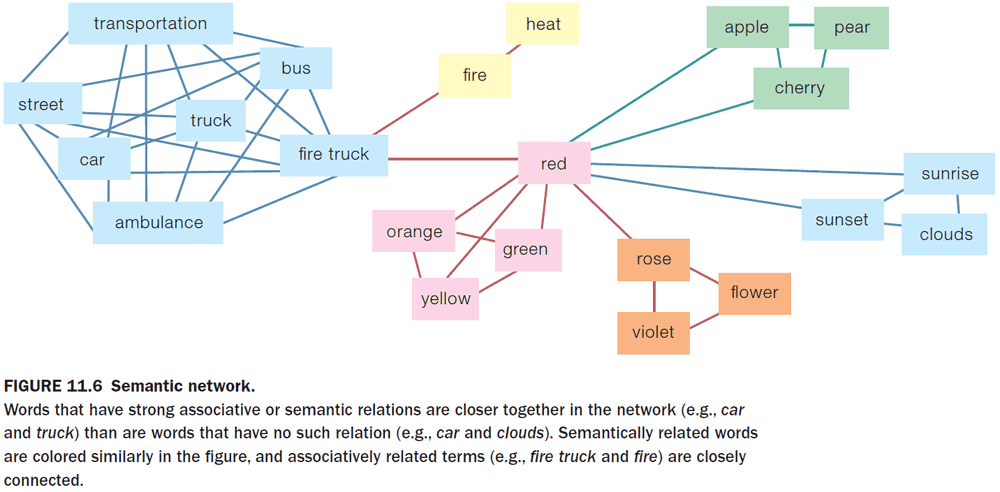

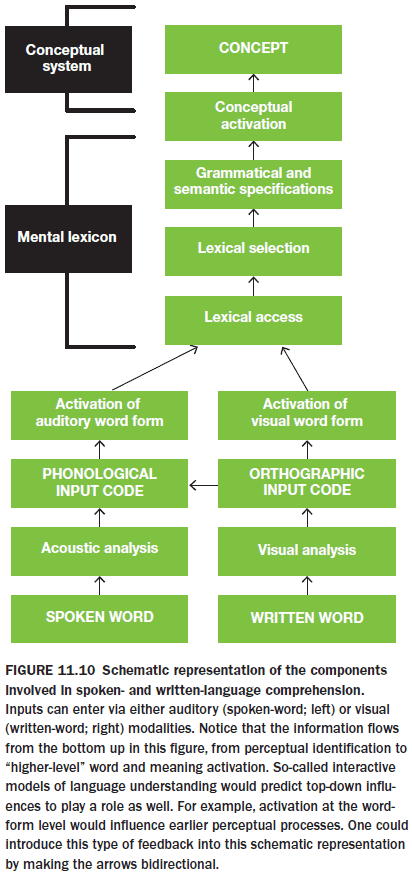

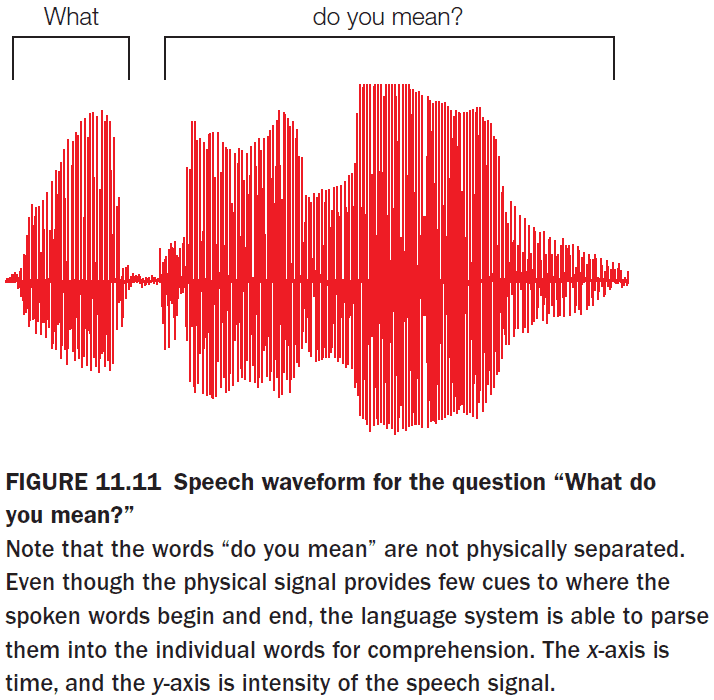

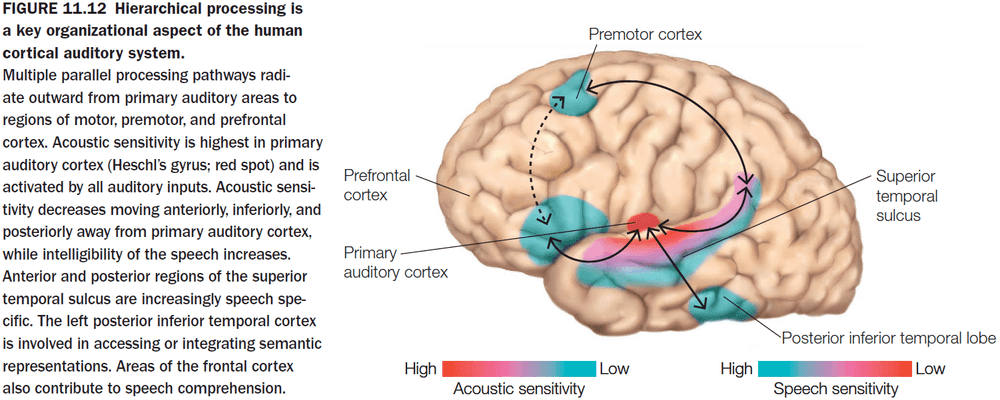

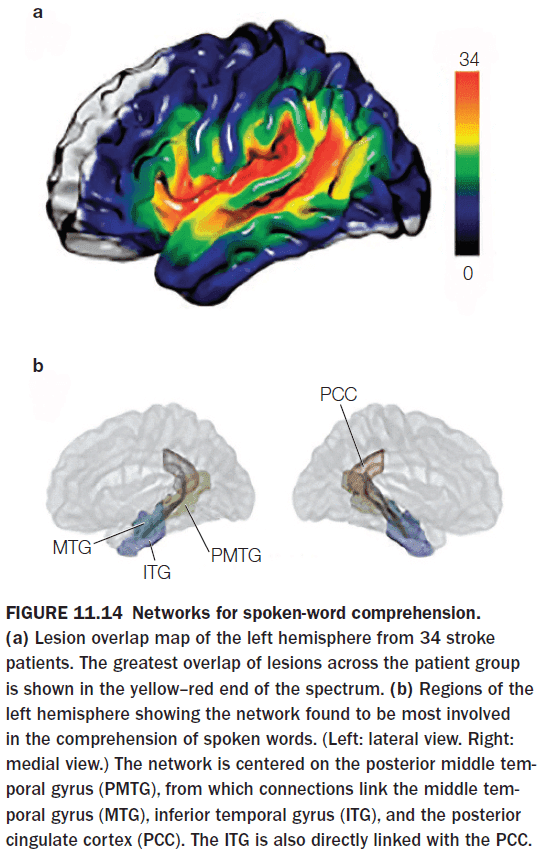

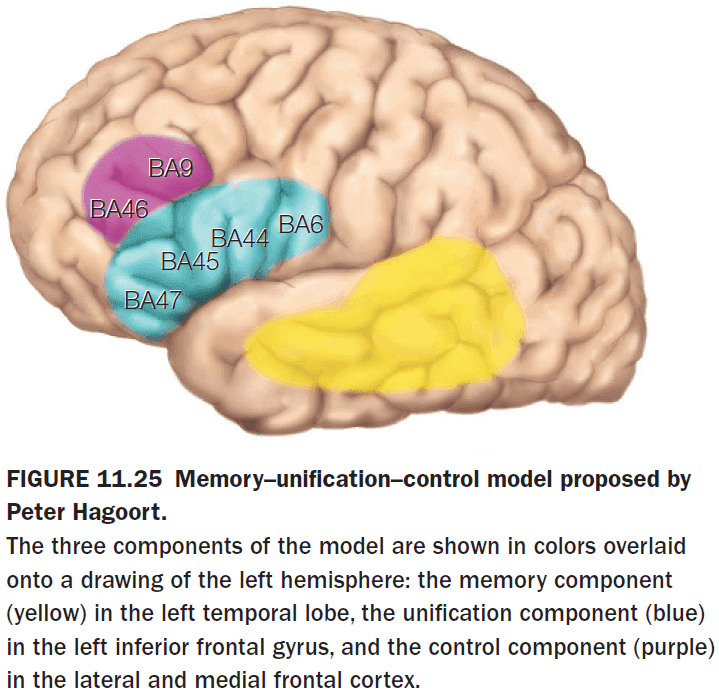

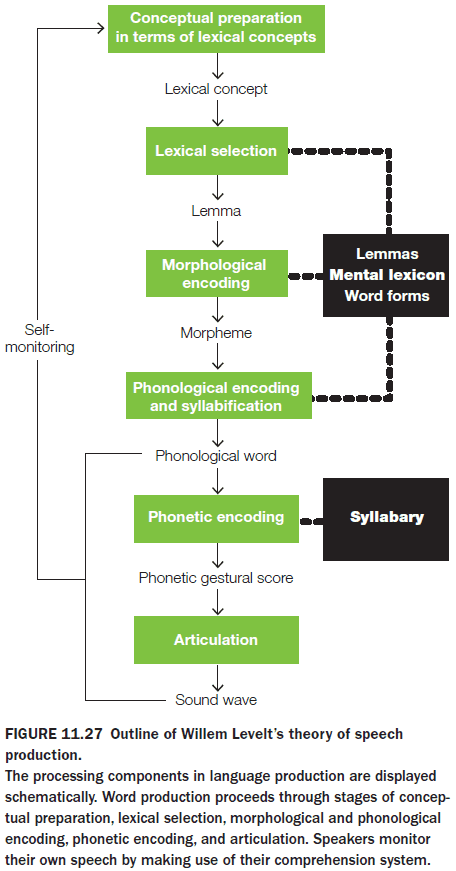

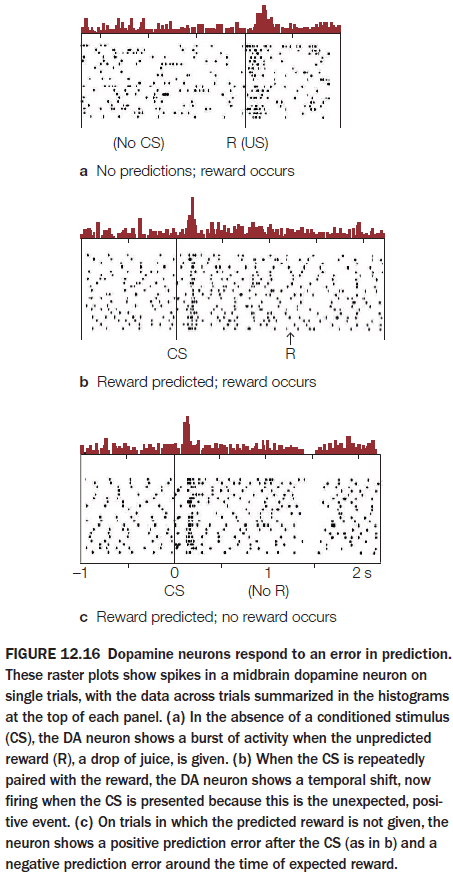

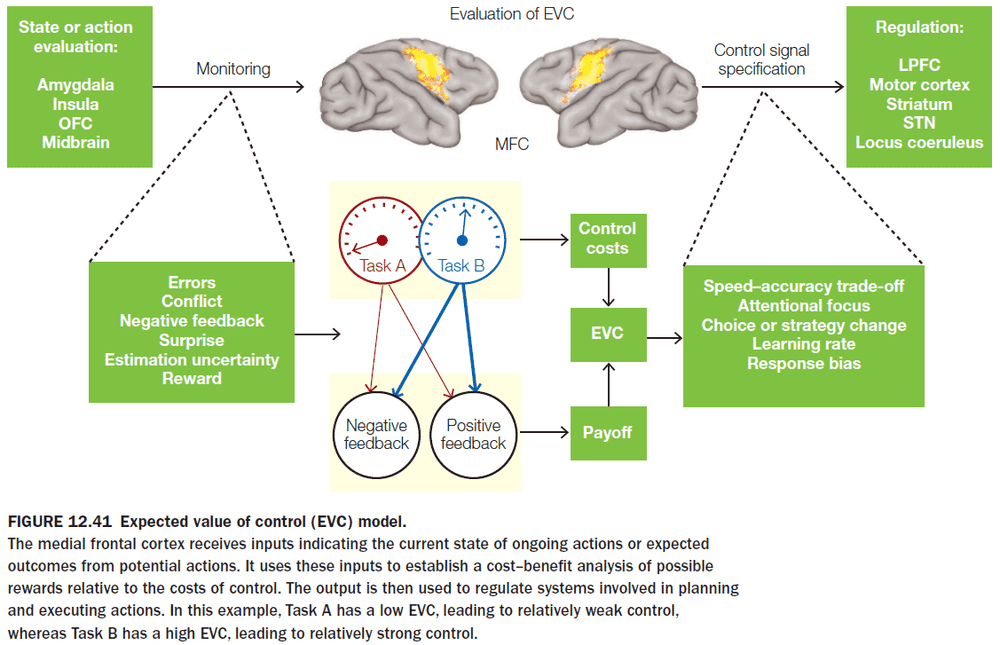

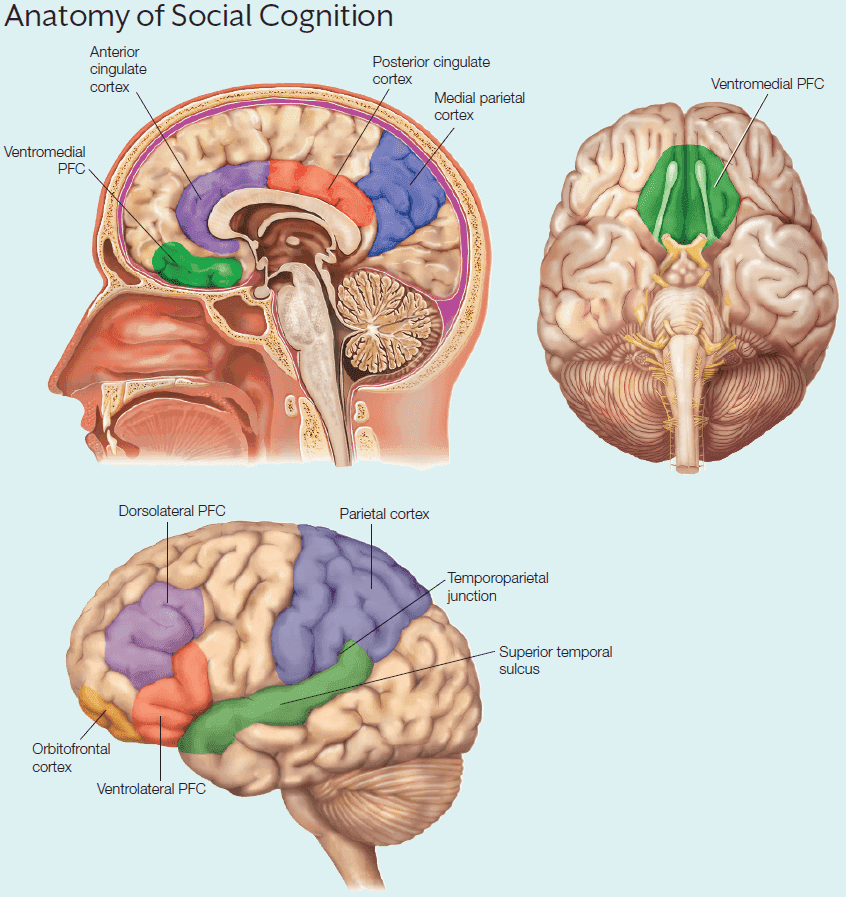

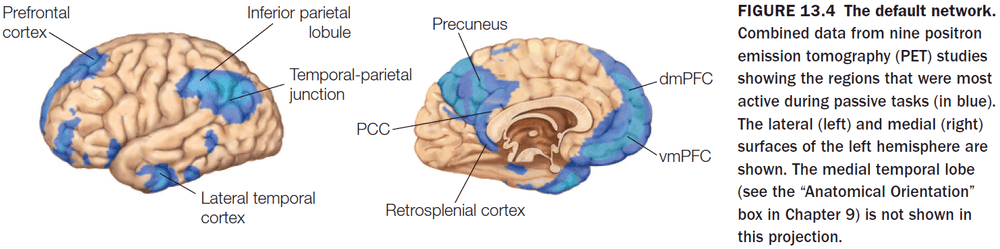

- One form of learning is adaptive learning through sensory feedback.