After Digital: Computation as Done by Brains and Machines

By James A. AndersonMay 08, 2019 ⋅ 26 min read ⋅ Textbooks

We don't live in a world of reality but in a world of perceptions.

Chapter 1: The Past of the Future of Computation

- The major theme of this book is that the design of computing hardware makes a huge difference in what computers can do and how effectively they can do it.

- Three flavors of computation

- Analog

- Digital

- Brain-like

- An analog device transforms one continuous quantity directly into another continuous quantity.

- E.g. Telephone converting sound pressure into electrical voltage.

- A digital device transforms analog signals into discrete signals.

- Quantization noise: the loss of detail from the conversion of analog to digital.

- Sampling rate: the intervals when a sample is taken from an analog signal.

- Given how poor digital phones transmit signals, why do they sound good?

- It sounds good because the brain fills in the missing details.

- If something is missing that past experience strongly suggests should be there, then put it there. Is this useful hallucination a bug or a feature?

- We will see other examples of this strategy in action in the visual system and in cognition.

- What a digital system loses in simplicity is made up in flexibility.

- An analog system for speech can only be used for speech unlike a digital system.

- One reason for this is that it’s very hard to write general-purpose software for parallel computers.

- Equating brain power and computer power isn’t easy because the hardware is different.

- Our cognitive software seems to be equivalent to the “alpha release” of a software product due to our cognitive biases, inconsistent language rules, and lack of critical thinking.

- The language of technology seems to be as close to a rich, universal, human language as we currently have.

- Perception: making sense of raw sensory data.

- Computers also undergo evolution as the best selling computers survive and are able to pass along their genes.

- However, this has lead to the evolution of computers that are useful to us in that they do what we do poorly.

- This has caused a separation between machine intelligence and human intelligence. We do what machines cannot and machines do what we cannot. A symbiotic relationship.

- It’s my feeling that to build a machine with true, human-like intelligence, it will be necessary to build into computers some of the cognitive functions and specialized hardware used by the one and only example of intelligence: us.

Chapter 2: Computing Hardware: Analog

- Computation is better defined by the task that’s performed rather than the hardware.

- Computation constructs aids to cognition.

- Analog systems can be programmed as they can take inputs and return outputs.

- The Antikythera device is an early example of a computer simulation. It’s able to simulate the position of the Sun and moon that matches observations.

- Flexibility of computation, the ability to compute the answers to new problems, suddenly became as important as accurate performance on old problems.

- Due to the flexibility of digital computers, a computer designed for artillery aim could be used to play video games, talk via social network, or store images.

- Multiplication for analog circuits is easily done via Ohms law. Set a resistor to one value and the current to the other value, then the voltage is the answer. It’s like we used reality to calculate the answer.

- Analog computers are much simpler and faster than digital computers. However, digital computers rapid increase in hardware speed hides the complexity of the programs that are required to solve problems.

Chapter 3: Computing Hardware: Digital

- Digital hardware is hardware that is based on two states.

- Other forms of computers

- Fluidic logic

- Optical computing

- DNA computing

- Game of Life

- Tinker toys

- Neurons

- Quantum computing

- Fast computers must be small computers due to communication costs.

- Brains have problems with some of the same limitations as do computers, just at a different order of scale.

- The speed of light is irrelevant to biological computation and heating can be handled with standard and well proven biological mechanisms.

- Conduction speeds in axons in the human cerebral cortex range from 0.1 meter per second to 100 meters per second.

- Just as in computers, designing the proper spatial arrangement to allow information to get to the right place at the right time is important and difficult.

- However, unlike computers, brains cannot shrink their components to improve performance.

Chapter 4: Software: Making a Digital Computer Do Something Useful

- The function of software is to make the computer usable.

- A Turing machine is a universal computing device.

- Turing machines cannot deal effectively with real numbers. It can only loosely approximate them using floating representations.

- The connection of logic to reality comes through the human assignment of a logic value to a voltage value.

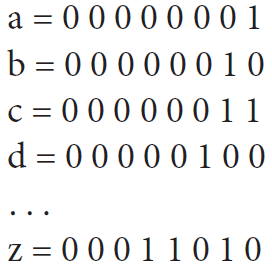

- A word is a group of bits. Words can be interpreted as either data or instructions.

- However, it’s important to realize that binary sequences of words like this are exactly and totally what any computer executes when it runs.

- That is all it does. Interpretation and intuition is the work of man.

- Subroutines are frequently used small programs or lines of assembly program with a common function used to avoid having to write the same instructions over and over.

Chapter 5: Human Understanding of Complex Systems

- Analogies help people understand complex systems but they must be wrong at some level of detail.

- First principles are the opposite of analogies.

- People approach complexity and problems with a huge amount of memorized material.

- Analogies based new ideas off of old ones. They also save time as it’s like a form of cognitive recycling.

- Analogies are always partially incorrect.

- “Information fluid” in the brain? How information is stored, used, sent, encoded, decoded.

- The brain acts like a central exchange in telephone networks. It connects inputs to outputs.

- Association: linking stimulus and response.

- Behaviorism only focuses on observable phenomenon, ignoring cognition.

- The computer as an analogy to the brain.

- Neuromorphic engineering: duplicating structure and function from the nervous system in artificial systems.

Chapter 6: An Engineer’s Introduction to Neuroscience

- Analog computers are fast and reliable but aren’t flexible and accurate.

- Digital computers are fast, reliable, and flexible but are hard to work with.

- Brains lie somewhere between analog and digital.

- What makes human brains special seems to be

- The connectivity between neurons

- The size of preexisting structures

- The operating parameters controlling excitability and inhibition

- This chapter is the “spec sheet” for brain-like computation.

- The brain is a “kludge” due to existing processes getting new functions. Think like how software must constantly adapt to changes which makes it spaghetti code.

- E.g. The brain has black-and-white TV but then discovers color. Instead of ditching the black-and-white TV, it keeps both and evolves both to serve different functions. Think rods and cones. This isn’t as optimal as designing the system from scratch.

- The claim is that many mental functions are modified from what they were intended to do.

- Desirable properties of neurons

- Spatial arrangement affects computation

- High degree of information integration via synapses

- Connections can change their strength

- Action potentials allows reliable long-distance transmission of information over poor conductors

- Undesirable properties of neurons

- Damage-prone

- High energy consumption

- Slow, noisy, unreliable

- Complex way of changing connection strength

- Sparse connectivity means a limited number of connections

- Instead of the neuron being the basic computational unit of the brain, what about small groups of neurons?

- E.g. Kidney and liver cells contain complex higher level structures.

- How is the brain organized?

- Nerves are mechanically sensitive.

- E.g. Funny bone and why the brain is protected by the skull. Rubbing your eyes causes “stars” because the pressure stimulates the retina cells.

- Nerves have high energy consumption which suggests that evolution cannot do any better.

- E.g. The brain requires about 20-40 watts.

- Brains are physiologically sensitive which requires homeostasis.

- E.g. The blood-brain barrier and Glia cells.

- The brain self-wires itself using chemical gradients to determine where to grow. However, cells that don’t correctly connect die.

- There’s a strong evolutionary pressure to retain as few neurons as needed because they’re biologically expensive. If you don’t use it, you lose it.

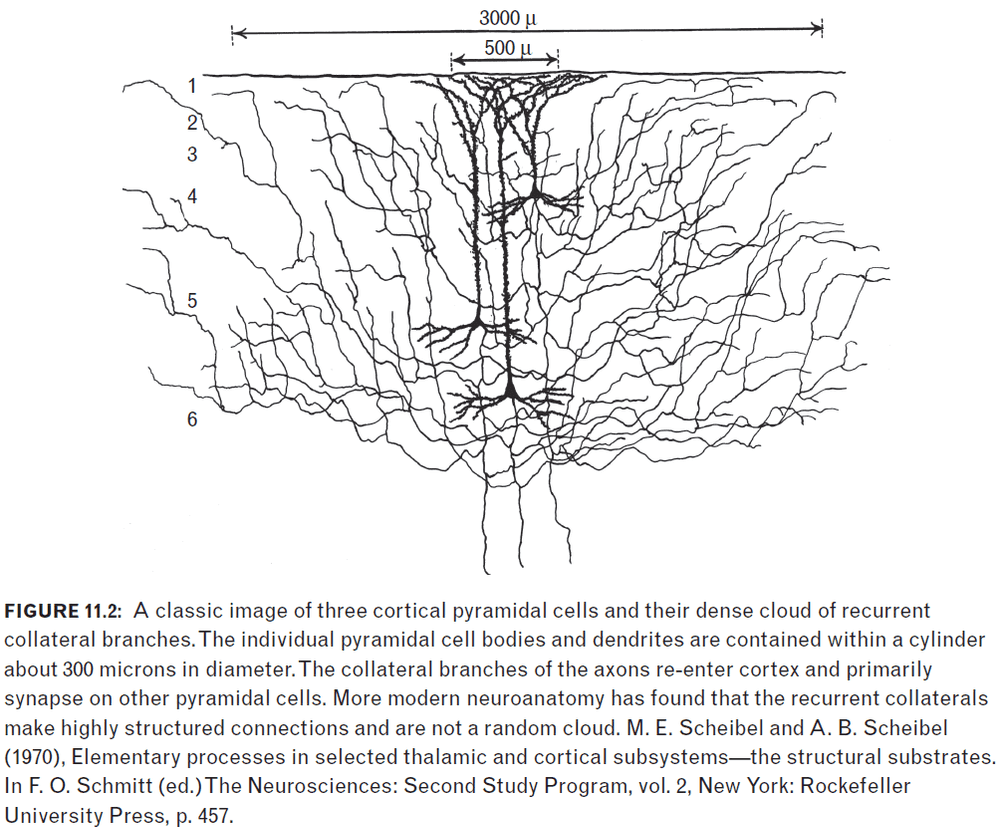

- Recurrent collaterals: axons of pyramidal cells that branch and connect to other nearby pyramidal cells.

- The membrane potential can be thought of as small batteries connected across the membrane.

- However, nerve membranes are thin and leaky; always letting some charge out.

- This is one of the main reasons why energy consumption of neurons is so high, it’s the cost of maintaining the membrane potential. If there was a better way to do it, evolution would’ve found it.

- Due to the membrane potential, the voltage gradient is 100,000 volts per centimeter. This is enormous.

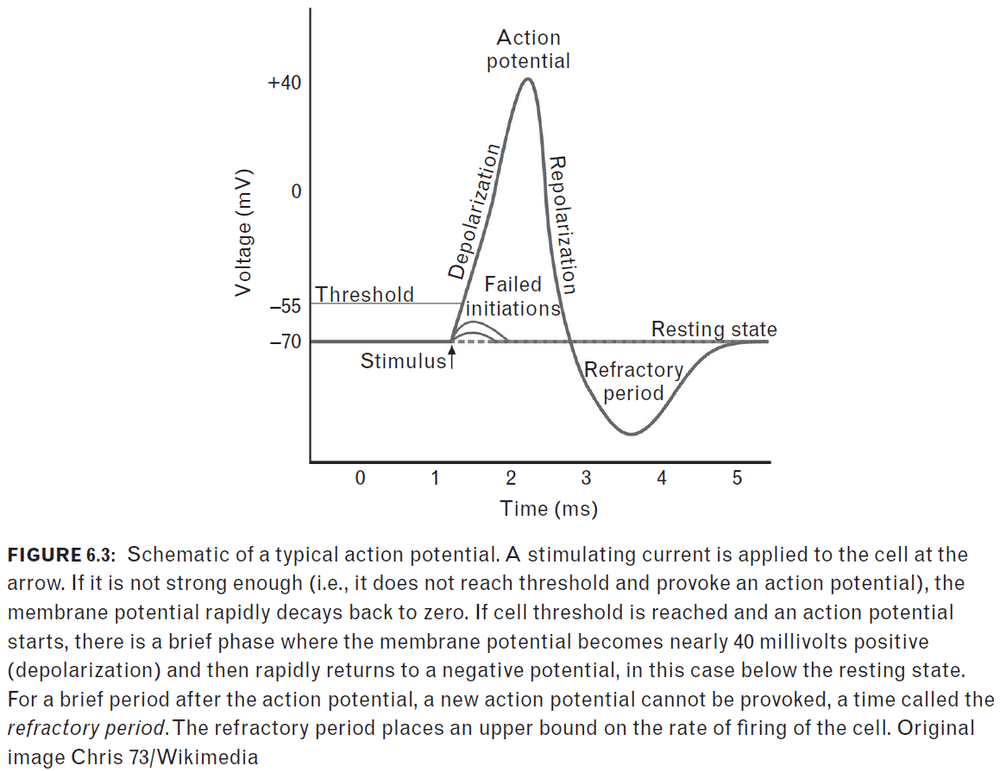

- If a battery is connected to the membrane and makes the membrane potential more negative, say from -60 mV to -70mV, nothing happens.

- However, if it makes the potential more positive, say from -60 mV to -50 mV, and it passes a “threshold”, then the membrane potential quickly goes positive, say to +40 mV, and then re-establishes itself.

- This phenomenon of quickly flipping voltage is called an action potential.

- It never changes shape; it’s either there or it’sn’t.

- The very high capacity and resistance of neuron membranes mean that their membrane potential will respond slowly to a changing input.

- Time constant: the time it takes for the voltage to decay by about two-thirds.

- Neurons have a time constant of a few milliseconds.

- Neurons are slow because the membrane has high capacity and resistance.

- The cable equation can be used to describe the neuronal membrane.

- Solving the cable equation solves for the time constant for membrane response.

- Space constant: the distance for the membrane potential in the axon to decay about two-thirds.

- Neurons have a space constant of a few millimeters.

- Not only are axons slow, but they’re also extremely poor conductors of electricity over long distances.

- E.g. The axon from the bottom of the spine to the end of our toes.

- APs exist to aid communication in the axon.

- One function of the action potential is to send information over long distances without attenuation.

- Neurons can increase the speed of APs by insulating the axon in a myelin sheath.

- Myelin sheath: an insulator that’s spaced apart on the axon to allow APs to jump between the gaps.

- By wrapping the axon in a myelin sheath, the construction of larger animals is possible.

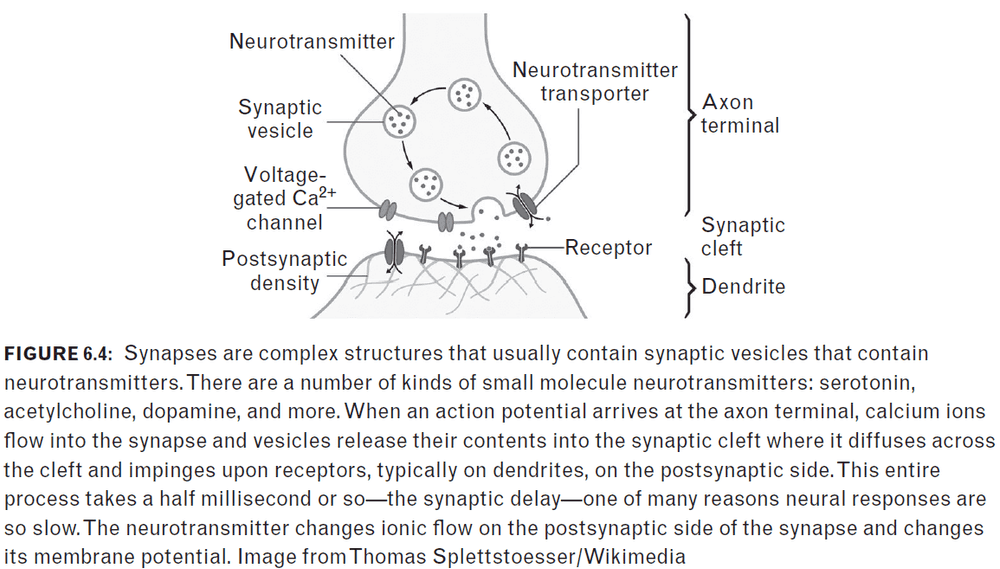

- The structure that allows information to flow between neurons is called the synapse.

- Synapses are more complex than neurons.

- Synapses use neurotransmitters to communicate information.

- There is little or no understanding of why changing a low-level synaptic mechanism affects mood at higher levels of the nervous system.

- E.g. Serotonin drugs to treat depression.

- When an AP reaches the input (presynaptic) side of the synapse, at first nothing happens. There’s a delay of around half a millisecond before any electrical activity occurs.

- Changes in the strength of synapses are where learning and memory are stored.

- Cognitive software has developed effective workarounds to compensate for the questionable performance of the hardware.

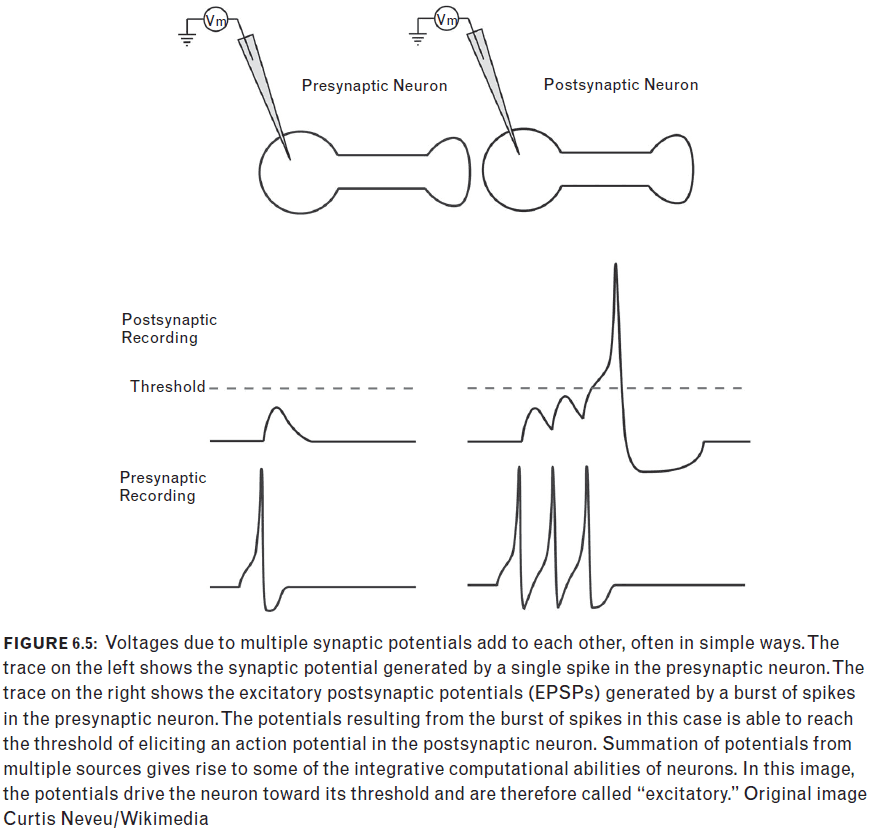

- The rate of firing differs depending on the size of the stimulating current.

- What the neuron is doing is converting a stimulus magnitude into a firing rate. It uses the rate of action potential discharge to send this information about stimulus size over long distances without attenuation. Sometimes this behavior is referred to as a voltage to frequency conversion.

- Converting the voltage to frequency sounds similar to the Fourier transform.

- The “strength” of a neuron’s response to an input is most often concerned with how rapidly the cell fires action potentials and for how long the discharge continues.

- Neurons have a dynamic range (what it’s capable of doing) between zero and a few hundred spikes.

- Contrast this with the binary range of digital computers.

- We can confidently predict that if nerve cells were faster the brain would work better.

- They can’t though due to fundamental physical constraints due to high membrane capacity and high resistance.

- A neuron emits a series of action potentials whose frequency of firing provides the result of the neuron’s “analog” computation from its inputs.

- Why are neurons slow?

- The membrane and its time and space constants

- The action potential itself

- Synaptic delay

- Voltage to frequency conversion

Chapter 7: The Brain Works by Logic

- McCulloch-Pitts neural networks had no memory of past events except what was remembered in the weights.

- The MP NN could compute any logic function which meant that they are at least as powerful as digital computers, if not more powerful/expressive.

- It’s interesting to realize that NNs can simulate digital logic which means they can simulate digital computers. So digital computers are a subset of NNs but we don’t know if there’s a computation that a NN can do that a digital computer can’t do.

- MP viewed the brain as a logic network which meant that it would be feasible to implement it in computers.

- von Neumann architecture: that the program would be stored in memory along with the data.

- The von Neumann architecture doesn’t work well for parallel computing nor for brain-like computation because of the separation between program and memory.

- Brain-like computation doesn’t have a clear separation between program and memory.

- Biological evidence doesn’t agree with the McCulloch-Pitts model of the neuron.

- E.g. Biological neurons are sparsely connected whereas artificial neurons are completely connected.

Chapter 8: The Brain Doesn’t Work by Logic

- Describing the way information is represented is the most important decision that someone building a brain-like computer must make.

- Details of representation correspond to probably the most important part of a cognitive “program.”

- Neuroscience lacks the ability to track a large group of neurons at the same time.

- There’s the belief that if we knew what every neuron in a brain was doing at a given time and knew the strengths of connections between them, we would understand how the brain works.

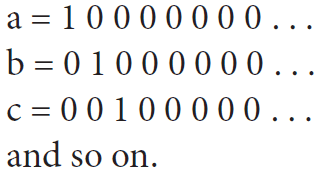

Selective representations

- Only one unit’s active for one concept.

- Also known as one-hot encoding.

- Are neurons extremely selective and only activate for one concept?

- E.g. Grandmother cell that only responds to grandmother.

- The evidence suggests no but there does seem to be highly selective groups.

- Reasoning

- The super selective cell doesn’t generalize well.

- Too dependent on one cell and if it dies, the concept is lost.

Distributed representations

- All units are active for all concepts.

- Is more efficient than selective representations because only 8 units are needed to represent 256 different concepts versus 26 units for 26 concepts.

- However, the problem with distributed representations is that it requires looking at all units.

- This doesn’t seem to happen biologically as not all neurons are active for all concepts.

- Binding problem: how to stick together the different active units that belong to the same event.

- How do spatially distributed nerve cells cooperate to act as a cognitive unit?

Sparse representations

- Sparse representations: a large, absolute number of neurons are activated for a complex event but is small compared to the total number of cells in the region.

- As processing moves further away from the sensory receptors, the representation seems to become sparser and sparser and more and more selective, but no selective representations.

- Analogy: The brain is like a piano player in that it has to play 2.5 million keys at the right time and hitting the right key, or else a disaster ensues.

Limulus: How the horseshoe crab sees a mate

- Convergent evolution: when evolution recycles a solution in another species.

- Lateral inhibition: a neural signal processing technique that’s seen over species when a neuron inhibits it’s nearby (lateral) neurons when they all fire.

- E.g. Suppose light illuminates a single neuron so it fires action potentials at a certain frequency. When its close neighbors are illuminated, its firing rate drops. Closer neurons are more strongly connected than more distant ones.

- The Limulus eye can be modeled as a linear time invariant system.

- All sensory-based neural structures we know of perform a sequence of processing steps of greater and greater complexity and of greater and greater refinement, leading ultimately to proper perception and behavior.

- Lateral inhibition is useful for edge enhancement.

- Dark areas near the edge look darker and light areas near the edge look brighter with a large rate difference between them.

- Lateral inhibition lets Limulus detect other Limulus for mating.

- There seems to be little, if any, learning. Wiring is under genetic control.

Frog eye: How the frog sees a bug

- The major result from the frog eye study is that the eye of the frog is well adapted to the lifestyle of the frog.

- E.g. The eye can very quickly spot a moving bug.

- The frog’s eye is only concerned with size and movement.

- Dynamic range: the range of light detection.

- Visual information sent to the brain is already highly processed as certain cells filter for certain properties.

- E.g. Rod cells for light intensity, cone cells for color.

- Both the topographic map and the selectivity of single units are required for allowing the frog to detect where the bug is.

- Since there is no evidence for the “grandmother” cell, the questions become

- How many cells form the representation

- What their behavior looks like

- There’s strong evidence that representations are “sparsely” represented.

Humans: How a human sees Jennifer Aniston

- This trend toward selectivity becomes increasingly pronounced as behavior becomes more complex.

- The optic nerve fiber has 1 million nerve fibers but the visual cortex has around 200 million neurons.

- As visual images are processed, the cell responses become more selective but over a wider and wider area of cortex.

- The representations gets closer to the grandmother cell but never reaches it. The cell responses are still highly selective.

- The active nerve cells showed a remarkable degree of invariance. That is, the nerve cells responded to a wide range of different examples of a particular concept.

- Cell responses were very general in their response to a specific concept. Different examples of the same concept got the same response from a neuron.

- Evidence suggests that relevant stimuli are encoded by a larger proportion of neurons than less relevant stimuli.

- The result suggested that whatever is binding units into complex concepts, first, operates quickly, and, second, is a normal mechanism of cognitive operation.

- Sounds like few shot learning.

- There seems to be an increase in abstraction along the MTL hierarchy that leads to the encoding of the meaning of the stimulus.

- There is a sparse cortical representation, with a few, but many more than one, active cells working together to form a higher level concept.

Cell assemblies

- The grandmother cell hypothesis is ruled out by the previous experiments.

- Cell assembly: a group of neurons that work as a unit.

- How do concepts combine?

- Rapid associations are formed but must be less selective about the association.

- Whereas the Limulus and frog nervous system processing is genetic, human processing isn’t as rigid and can learn via associations.

Chapter 9: Association

- We have no theories in brain science or cognitive science in the way that physics has theories.

- Physics theories can be compacted into a few lines of math that predict a wide range of phenomena.

- E.g. Maxwell’s equations for light, electromagnetism, radio waves, motors.

- The closest thing we have in brain science is association.

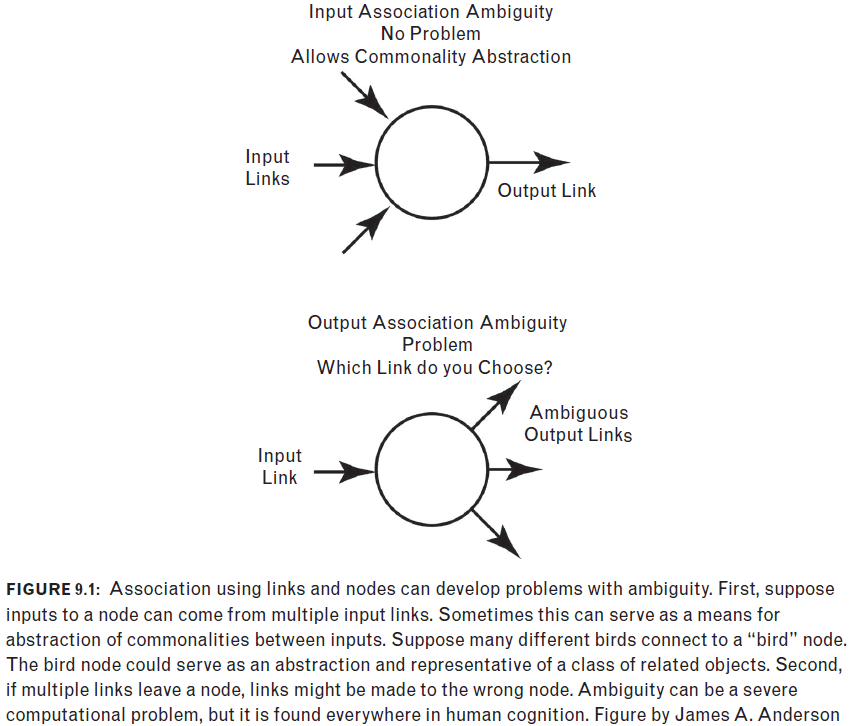

- Association: different events become linked together through learning.

- The links can be used for memory, reasoning, generalization, and inference.

- The fundamental unit of memory is sense images.

- We can link/associate different sense images to form more complex ideas.

- Sense images don’t have high resolution nor high accuracy which means they’re unreliable.

- James’ three computational assumptions

- The items that are associatively linked contain components parts.

- Since there are many links between sub-components, it’s likely that more than one link will be active at a time.

- Links become weak or strong through a learning process.

- Instead of a single link for a single association between events, there are now many links joining the component parts of input and output together.

- Simultaneity of activation allows integration of activity arising from the sub-components.

- Connections can have different strengths based on their history and activity contributions are added, weighted by the strength of the connections between them.

- Hebb rule: neurons that fire together wire together.

- However, how much “firing together” leads to how much “wiring together”?

- What’s critical for the Hebb learning rule is that the inputs and outputs must be correlated in their activity for synaptic change to occur.

- The strength of the synapses then contains contributions from both input and output.

- Even this simple associator can only remember “factoids”.

- Factoid: isolated facts.

- To create a more general and flexible network, the factoids have to be integrated into a more complex conceptual network.

- The more facts a fact is associated with, the better it’s memorized. Each of it associates becomes a hook to which it hangs, a means to fish it up when sunk beneath the surface.

- The secret of good memory is to thus have diverse and multiple associations with every fact that we want to remember.

- E.g. Memory palace associates a place with a memory or the Russian reporter with synesthesia.

- This parallels computers as simple memory is stored but only through software can complex associations of memory be created to do work.

- Problems with simple association

- Literal: an input links to an output and that’s it.

- Control structures: instead of using all inputs, only select a few to launch the association.

- Logic: associative networks have no relationship to logic.

- What is the physical basis of memory?

- Memory is stored in the synapses that couple nerve cells together via the synapse’s strength.

- The connection between change in synapse strength and change in behavior has been conclusively shown.

- E.g. Aplysia work by Eric Kandel.

- However, the changes are complex and not well understood.

- The Hebb rule is only concerned with excitation, what about inhibition?

- Spike timing dependent plasticity (STDP): synaptic modification based on the AP arrival time at the synapse.

- If the input AP arrives before the output AP, then the synapse is strengthened.

- If the input AP arrives after the output AP, then the synapse is weakened.

Chapter 10: Cerebral Cortex: Basics

- Cortical structure is surprisingly simple with relatively few cell types and a nearly uniform organization across most regions.

- Cerebral cortex: the outside surface of the human brain.

- It’s similar to the rind on an orange peel.

- Grey matter: the cell bodies on the outside of the brain.

- White matter: the bundle of axons. It’s white due to the myelin sheath on axons being white.

- To fit the large surface area of the cerebral cortex into the skull, it has to be folded up hence the wrinkles.

- The main problem of equating brain size with intelligence is that larger animals have larger brains.

- Cortical computations depend critically on bringing information together at the same place and at the same time.

- Since neuron responses are slow, there needs to be a careful arrangement of components to make the timings come out right.

- It’s believed that the folds reduce the length of connections and thus makes the responses faster.

- Evidence indicates that there is little that is structurally new in our brains other than change in size.

- However, it’s likely that there have also been a series of changes in the details of the hardware and its connections that make this large brain work better and let it develop and use better software.

- The problems with big brains

- Increased communication delay between neurons

- Long gestation period (baby brain is a third the size of an adult brain)

- Difficultly in getting the baby born

- The cortex is composed of 100 distinct regions known as Brodmann regions.

- The regions are similar but slightly different.

- Applying our understanding of electronic information flow to brains doesn’t work well because it’sn’t a clean input to output processing.

- In the visual cortex, nearly every visual region talks to every other visual region and the connections are two way.

- There’s a weak hierarchy among the regions but no rigid flow of information from sensation to perception to cognition.

- Even though the regions look anatomically homogeneous, they contain internal structure when looked at functionally.

- Some regions form a map of the 2D body surface onto the 2D cortex.

- The more cortical space devoted to a function, the more important it’s for the animal.

- One guess is that each neuron adds a roughly constant amount of processing power.

- An increase in correlation between cells can cause a demonstrable change in the cell’s response.

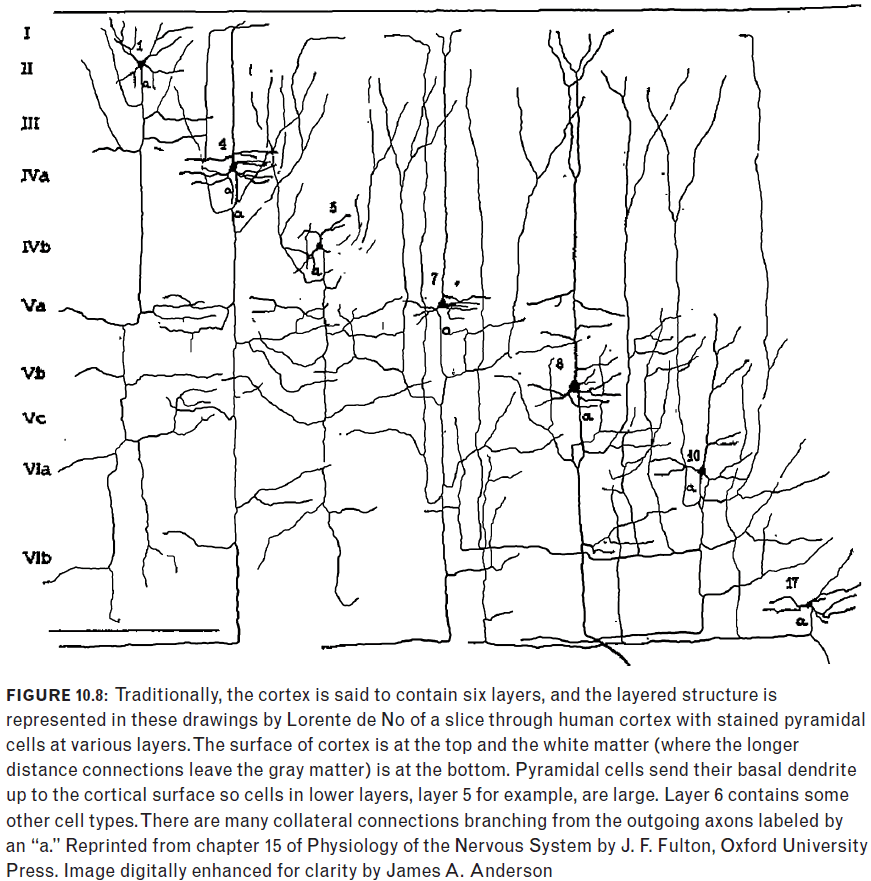

- About 80% of the cells in the cortex are pyramidal cells.

- Most of the cerebral cortex is made up of 6 layers.

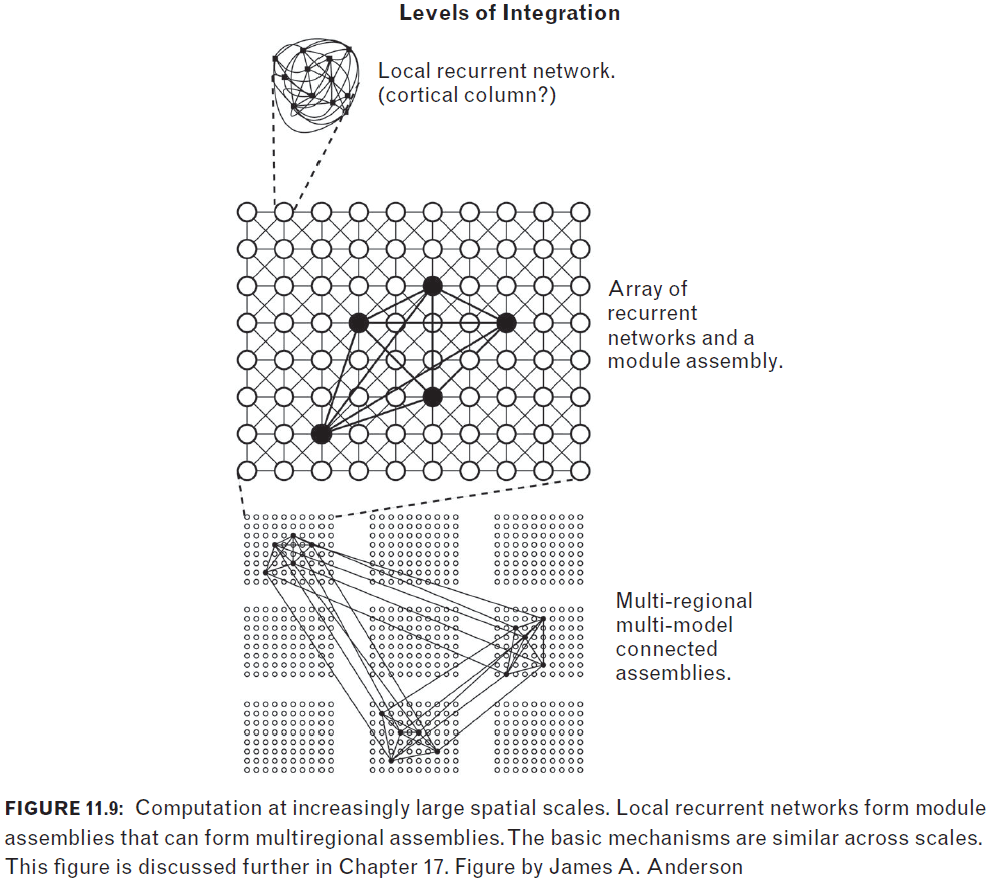

Chapter 11: Cerebral Cortex: Columns and Collaterals

- The brain’s white matter is formed of long-range connections from cortical region to cortical region.

- If it’s not of importance, don’t respond to it.

- Unlike an ANN, brains have sparse connectivity.

- The cortical processing chain is flat without many sequential steps.

- Candidates for local interactions

- Recurrent collaterals: axons connecting nearby pyramidal cells.

- Cortical columns: an intermediate level of neural organization where nearby cortical neurons seem to work together.

- There is substantial local processing power as shown by the large number of local connections.

- A negative feedback system leads to a virtuous circle.

- A positive feedback system leads to a vicious circle.

- Since a lot of the connections in the cerebral cortex are excitatory, it would lead to a positive feedback loop and quickly lose stability.

- Re-excitation is potentially dangerous in leading to hyperexcitability and seizures. Inhibition is therefore needed to oppose or modulate this potentially strong excitation.

- Cortical circuits can thus be seen to be poised on the knife edge of excitation restrained by inhibition, one of the risks of the computational power of the cortical microcircuit.

- However, positive feedback lets a system respond very quickly since the signal is amplified.

- Positive feedback can be selective in that the system may only respond strongly to one part of the input.

- Perhaps attention is implemented as positive feedback?

- The basic unit of cortical operation is the minicolumn.

- Minicolumn: a column of 80 - 100 neurons that’s built from birth.

- Cortical columns: a collection of minicolumns bound by common input and short horizontal connections.

- Cortical expansion in evolution is marked by increases in surface area with little change in thickness.

- Sometimes it’s better to reduce extreme selectivity to reflect underlying real world similarities.

- Neurons → Minicolumn → Cortical column → Cortical region

- The entire region is mostly uniform and usually has a topographic map.

- E.g. Vison → space, Audition → frequency, Touch → body surface.

- There is a speed-accuracy trade off in cognition.

Chapter 12: Brain Theory: History

- One large-scale organizing principle of the brain is association.

- There aren’t any high-level theories in neuroscience but there are many “ad hoc” theories.

- Ad hoc theory: explains one or a few experiments but not much more.

- It probably isn’t a coincidence that logic-based computers and logic-based brain theory developed simultaneously. However, it’s wrong.

- Good brain theories explain both the behavioral and neural levels.

- E.g. Lateral inhibition in Limulus for reproduction and the frog’s eye for seeing bugs.

- Engineers write poetry. Scientists write prose. Scientists see what is and try to explain it. Engineers try to make what never was.

- Engineering problems with neural networks

- Accuracy

- Capacity

- However, it’sn’t necessary to store everything, only store the important stuff.

- Control associations through attention-like mechanisms.

- Integrating lots of information from the real world and forming generalizations is like induction.

- “Instances of which we have had no experience resemble those of which we have had experience.”

- Humans seem to make little use of rational reasoning in daily life and almost none of logic.

- Many cognitive scientists believe that “fast” thinking is old biologically and that “slow” thinking is new and largely confined to humans.

- Free association tends to traverse the stronger rather than weaker links.

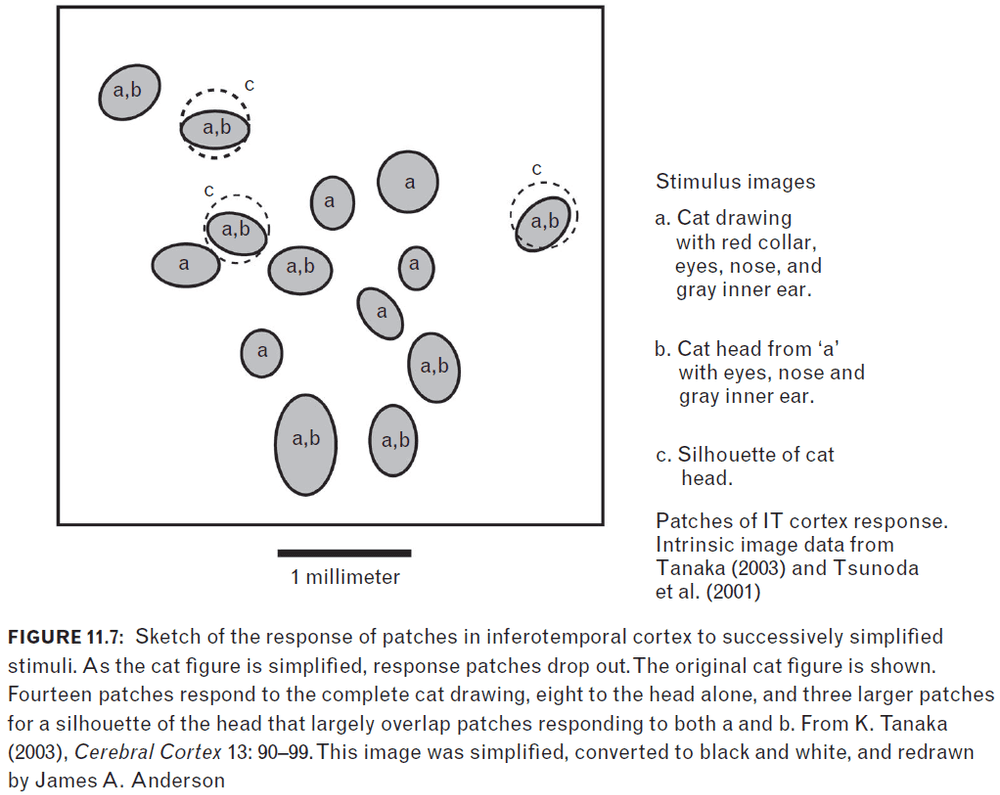

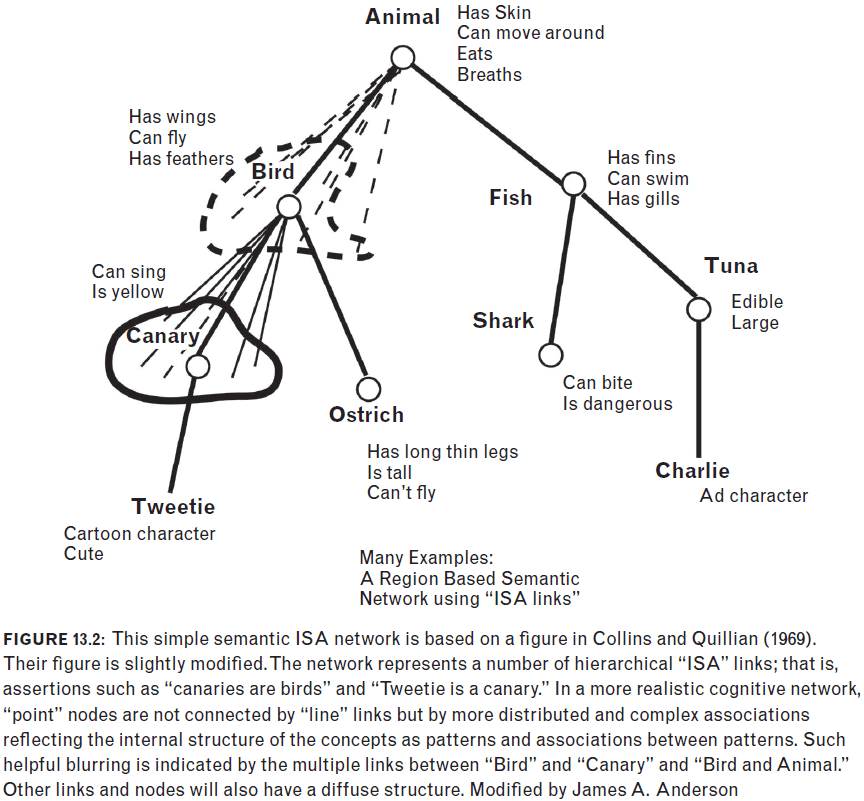

Chapter 13: Brain Theory: Constraints

- The elementary particles of cognition are concepts.

- Brain-like computation is the result of the hardware constraints that it must work with.

- In the brain, hardware and software are almost the same thing.

- Compression trades storage space for processing power.

- The brain performs lossy compression since it removes irrelevant details.

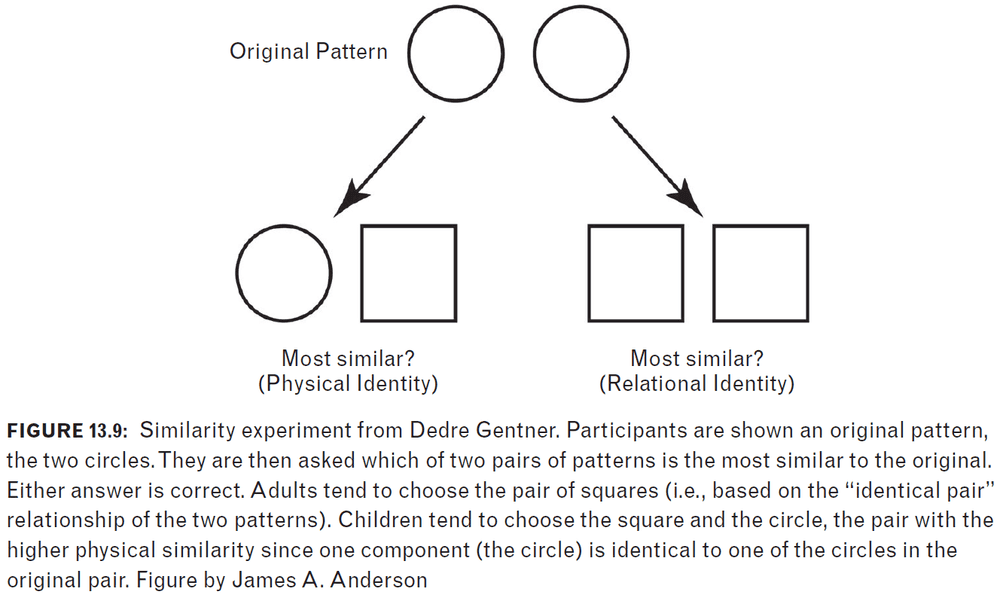

- Central and peripheral members of a category are often used somewhat differently in practice.

- E.g. “There’s a bird on the lawn” versus “There’s a penguin on the lawn”.

- Important experimental results about concepts

- People are good at determining whether an example is a central or a peripheral member of a category.

- The response time for central members is faster.

- A central member of a category tends to be used as the default in a sentence. Think common sense.

- Concepts hold the useful regularities found in the environment. Think pattern recognition.

- Associative memory is composed of two parts

- Sensory-based information, memories, is the raw material of cognition.

- Memories can become associatively linked to form a network.

- Semantic network: a network that represents the semantic relations between concepts.

- An ISA semantic network not only saves memory by reducing duplicates, it also can answer queries by moving among the nodes.

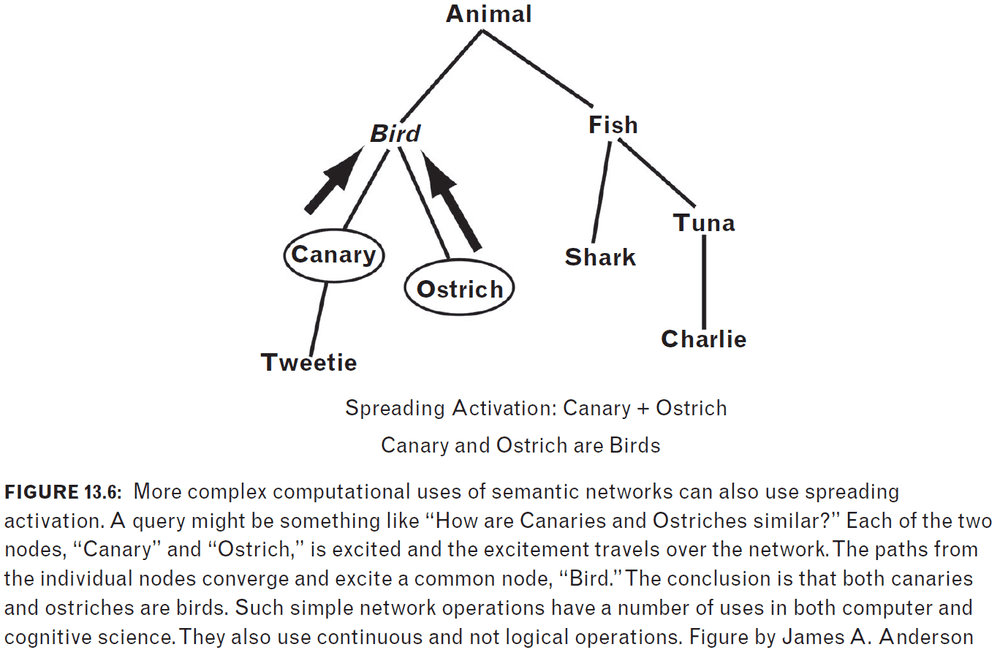

- Spreading activation: a “level of excitement” of each node that can spread to connected nodes.

- E.g. “What do canaries and ostriches have in common?” would make the bird node twice as excited.

- Another property of semantic networks is that they can be queried without updating the network. So inferences can be drawn without learning from an external source.

- The use of summed network excitation from multiple weak sources of information is what the brain seems to do. It also makes it seem like the brain is just an amplifier.

- The idea that cognition incorporates an active search for meaning is central to most forms of brain-like computing.

- Popular machine learning techniques tend to separate information processing (updating weights) and network dynamics (how long to update the weights).

- This is unfortunate because response time matters as shown by psychology experiments.

- How long it takes to get an answer can often be just as or even more informative about the inner workings of a system as the correct answer itself.

- ANNs forget the aspect of time in processing.

- “If a phenomenon is important for our welfare, it interests and excites us the first time we come into its presence. Dangerous things fill us with involuntary fear; poisonous things with distaste; indispensable things with appetite. Mind and world in short have been evolved together, and in consequence are something of a mutual fit.”

- Sensory data is easier to represent than conceptual or abstract data.

- E.g. Colors versus logic.

- Nothing recurs exactly. Therefore, proper cognitive operation requires that behavior generalize properly.

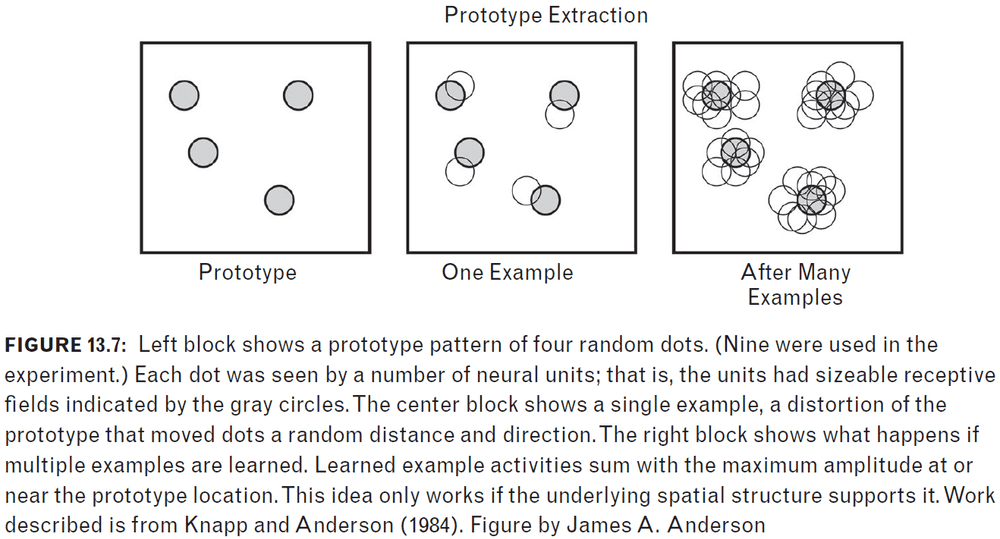

- The signal processing technique of averaging different examples.

- Associative learning with proper data representation is capable of extracting concepts.

- Two powers of our cognitive system

- Generalization: taking something specific and applying it more broadly.

- Abstraction: removing unnecessary details in a model to create something that isn’t concrete.

- Generalizations create abstractions.

- Both the learning and the data has to be present and properly matched to get the right generalizations.

- A different representation would’ve failed in figure 13.7.

- E.g. Instead of a visual representation, suppose the location of the dots was represented as a string of 0s and 1s so that if the dot moved, the string would be completely different. No generalization would be possible as there isn’t a link between the dots and the string.

- Think hash table. If I hash similar objects to similar locations, it’s easier to learn the pattern then if it were hashed randomly.

- Sometimes accuracy can be the enemy of generality.

- Memory abstracts only what the details allow it to abstract.

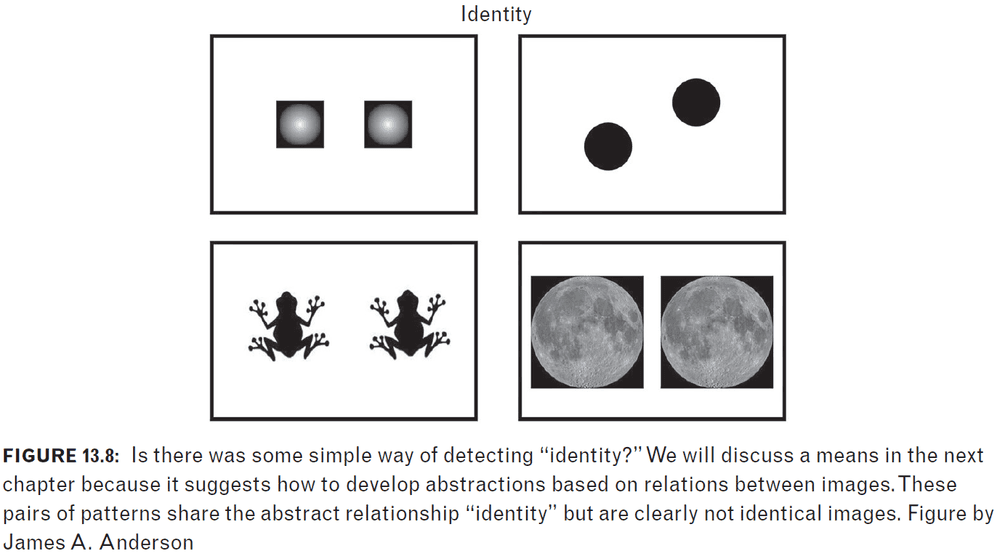

- An extreme example of abstraction is “identity” or how things are identical.

- The ability to generate abstract relationships and good generalization is not accurate pattern recognition but is something different and much more interesting for higher level cognition.

Chapter 14: Programming

- Data representation: the set of neural discharges that respond to an event.

- The key to brain-like computation is to get the data representation fitted to the problem.

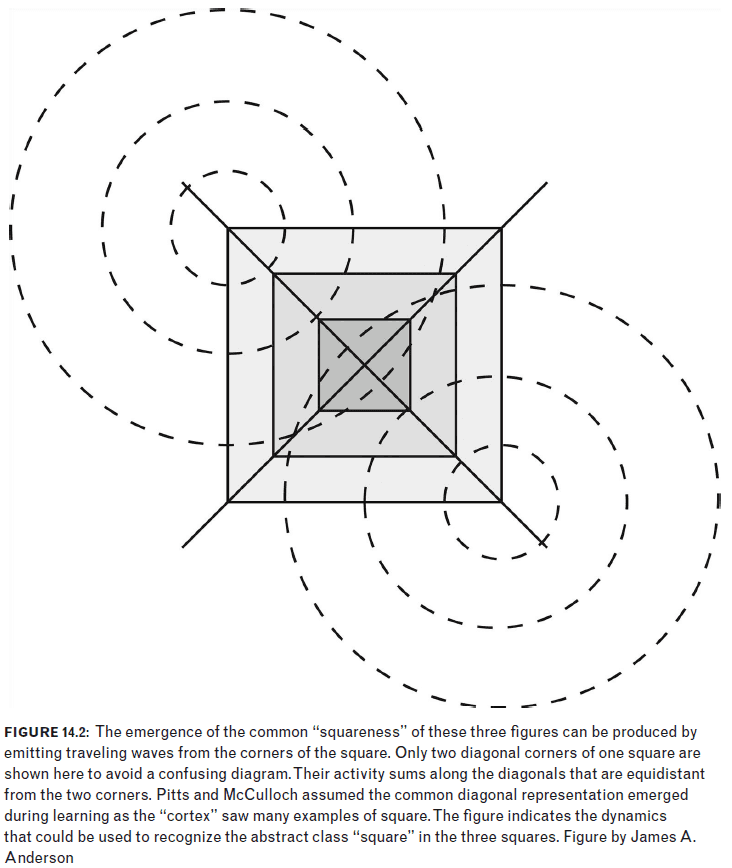

- There must be something in perception representing this invariant commonality derived from the shape.

- The brain is able to “generalize” image viewpoints.

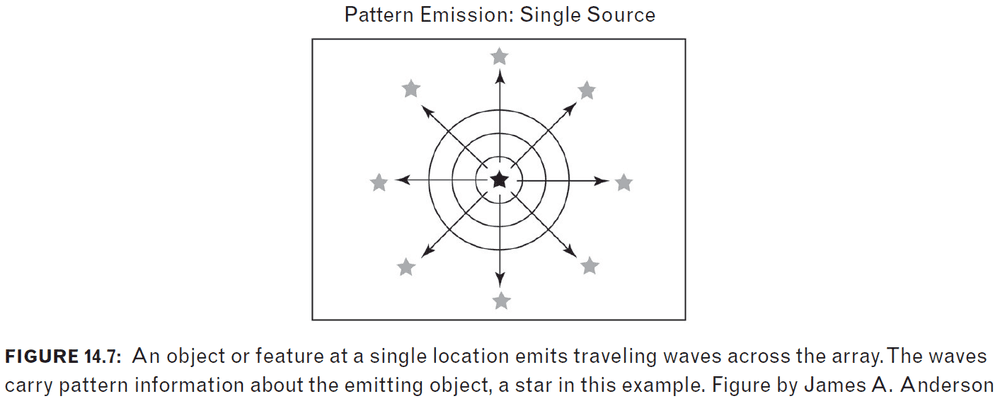

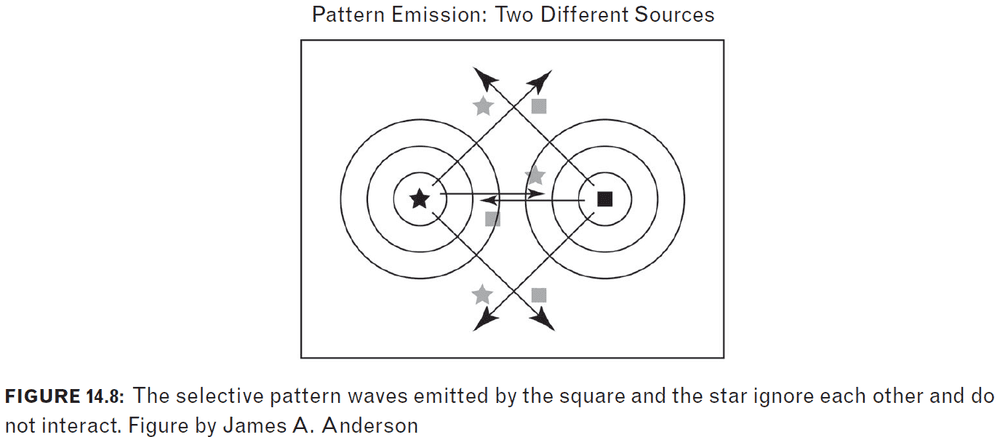

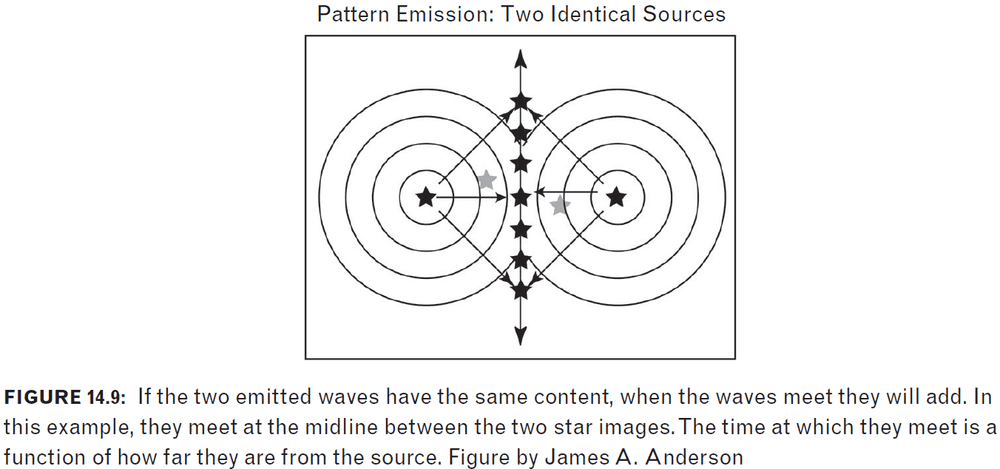

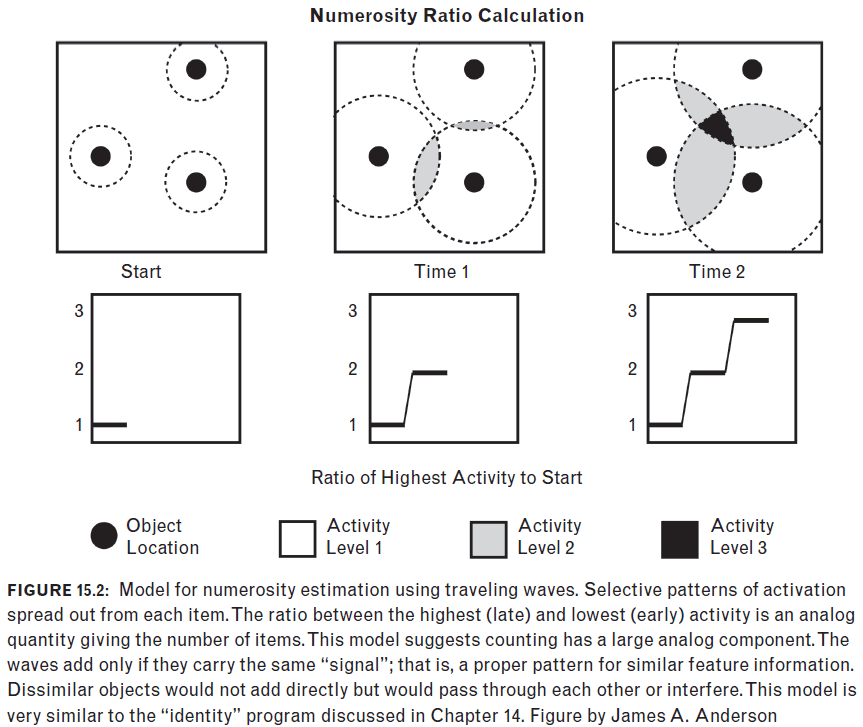

- Traveling wave: a wave of spikes in neurons.

- This reminds me of how our brains might determine where a sound comes from by timing when the two audio signals from both ears meet.

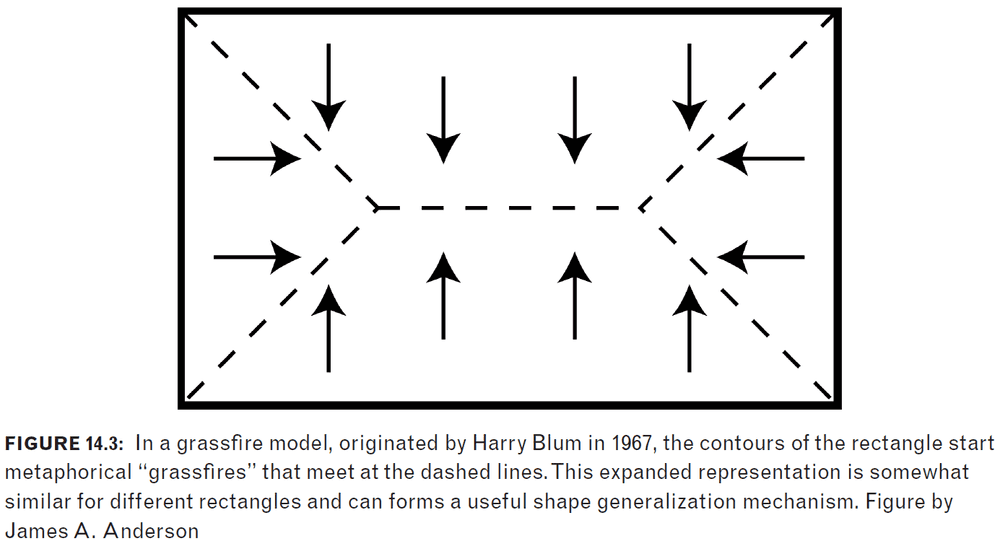

- Medial axis representation: representations where the shape is extracted from an axis that’s equidistant from all edges.

- There are more cells in the visual cortex than there are incoming fibers in the optic nerve.

- 300 million neurons in the primary visual cortex versus 1 million optic nerve fibers.

- Maybe identity is also “calculated/determined” via traveling waves.

- This also provides a basis for determining the similarity between items. Maybe the larger the resultant wave, the stronger the identity.

- This can also be applied to determining symmetry.

- However, identity and symmetry don’t exist in reality as they’re abstractions created by humans.

- Identity and symmetry are both a measure of the degree of similarity which is useful.

- E.g. This apple is the same as the apple I previously ate so it should be OK to eat.

- Perhaps this is why we find beauty in symmetry and in people that look similar to us.

Audition

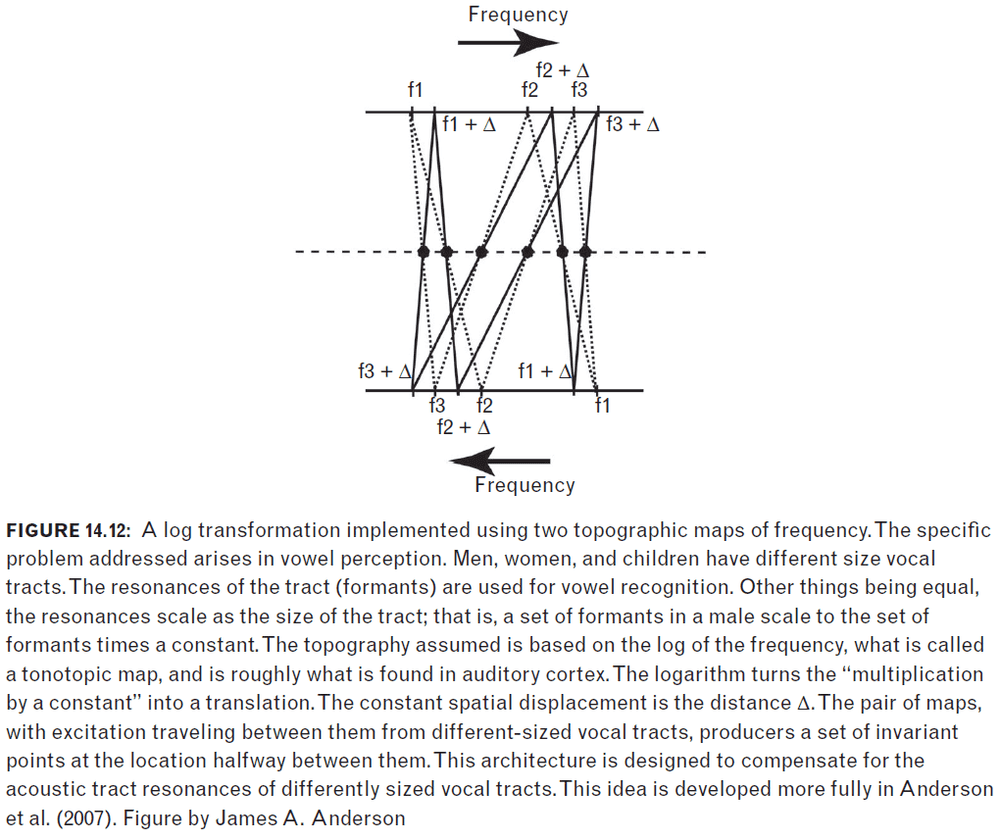

- Men, women, and children have different size vocal tracts yet we seem to understand each other most of the time.

- Even though the vocal tracts are different sizes, it still maintains its shape so while the frequencies of sound vary, the ratio between frequencies is stable.

- It’s suggested that a spatial system that responds best to ratios of frequencies and not to absolute frequencies can recognize sound.

- Logarithms provide a possible mechanism for implementing this invariance towards frequency.

- Important abstractions can be produced from properly constructed topographical mappings combined with traveling waves that doesn’t involve logic or binary arithmetic.

- Well-developed sources of related good ideas to borrow can be found in optics, antenna design, and complex mechanical linkages, all of which depend on a careful mingling of geometry, desired function, and interacting selective wave- like signals.

- Using traveling waves as a form of computation reminds me of how we can multiply by running a current through a resistor and measuring the voltage.

- It uses the natural world do the calculation.

- Invariance, generalization and abstraction are the same thing.

- For a computing system based loosely on cortical architecture, it’s possible to let geometry do much of the processing.

Chapter 15: Brain Theory: Numbers

- Humans seem to use a hybrid strategy of analog components combined with discrete ones to work with numbers.

- Numerosity: counting or the set size of a group of items.

- Numerosity is independent of location and identity.

- For between one and five items, humans count by subitizing.

- Subitizing: humans “know” quickly and effortlessly how many objects are present.

- Each item adds up to 40 milliseconds to the response time up to five items.

- Past five items, each additional items requires 300 milliseconds and conscious awareness.

- There isn’t any explicit upper limit for consciously counting but there is for subitizing.

- Are there specific cells for numerosity/counting?

- There are “bug detector” cells in toads, “face cells” in monkeys and humans, and “place cells” in humans. Aren’t these examples of neuron selectivity?

- Numerosity can also be calculated via topographical maps and traveling waves.

- This fits the experimental data as

- Additional items require more time for the waves to interfere.

- It computes both numerosity and similarity.

- Too many items crowd the network or cause inhibition or we just don’t have the networks for more than five items.

- Why, if we have been in more or less the same biological form for more than a hundred thousand years, did it take so long for us to get smart?

- Perhaps cognitive evolution is very slow and difficult due to abstractions being easy to see, but not easy to name and communicate.

- Observe the system.

- Look for emerging invariances.

- Give it a name.

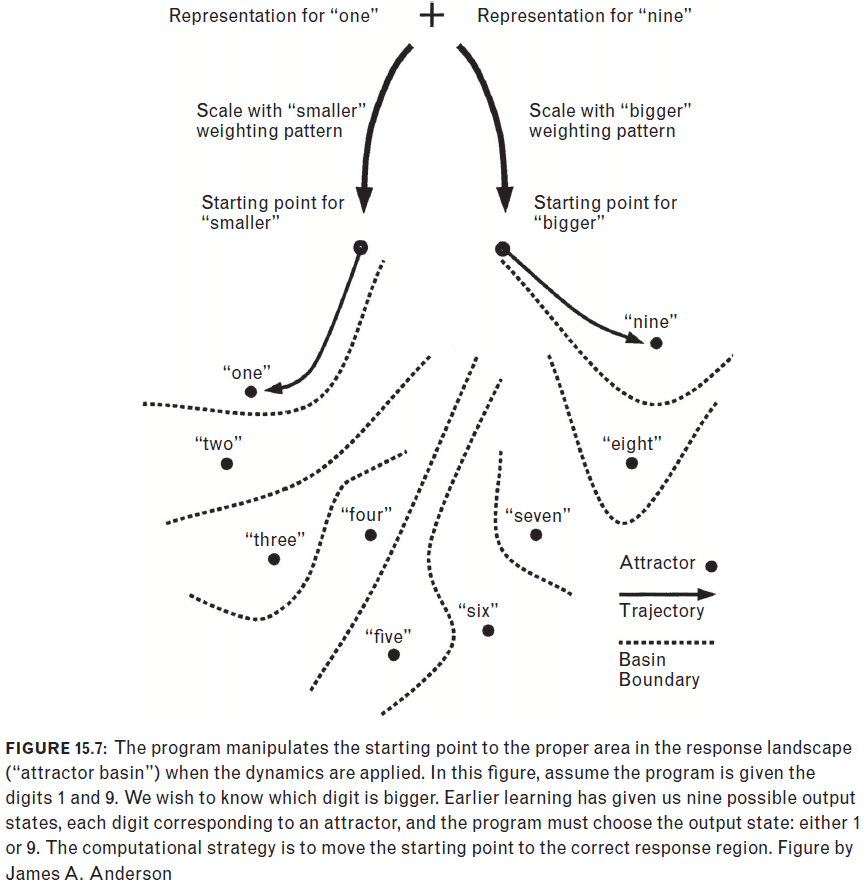

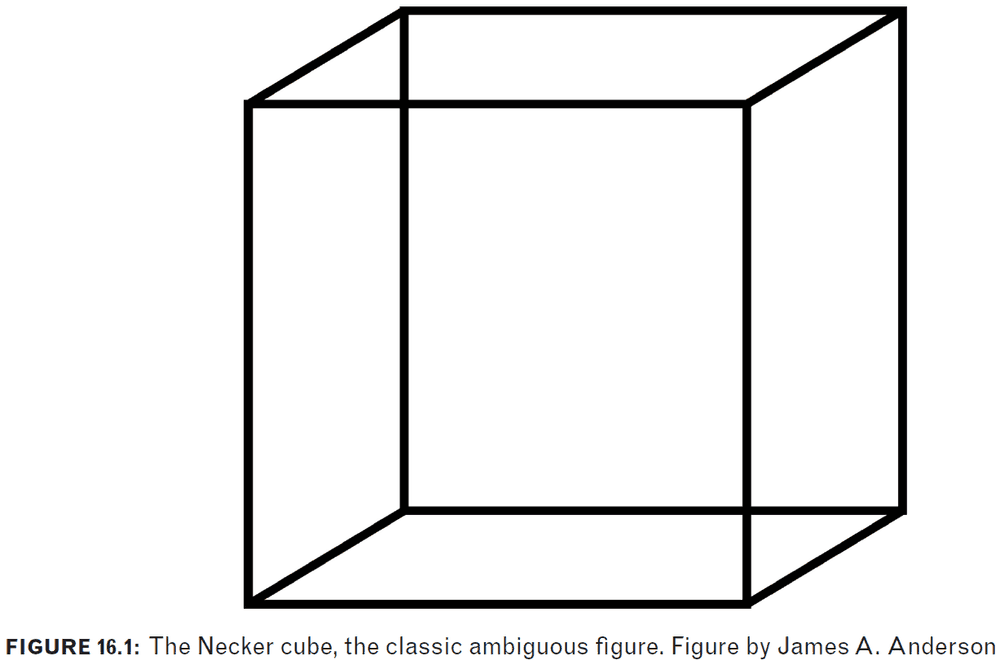

- Ambiguity causes problems for simple associative systems because the same input can lead to different outputs.

- To clear up ambiguity, use additional information from the context.

- An interesting cognitive experiment to compare intensities

- Which is greater? 11 or 99?

- Which is greater? 73 or 74?

- It takes longer for people to answer the second question.

- This delay when the gap is smaller is also seen with sensory stimuli such as which is louder, brighter, or heavier.

- The delay is known as the “symbolic distance”.

- Computers don’t have this delay as they calculate the difference between the two numbers and check the sign. it’sn’t dependent on what the actual numbers are.

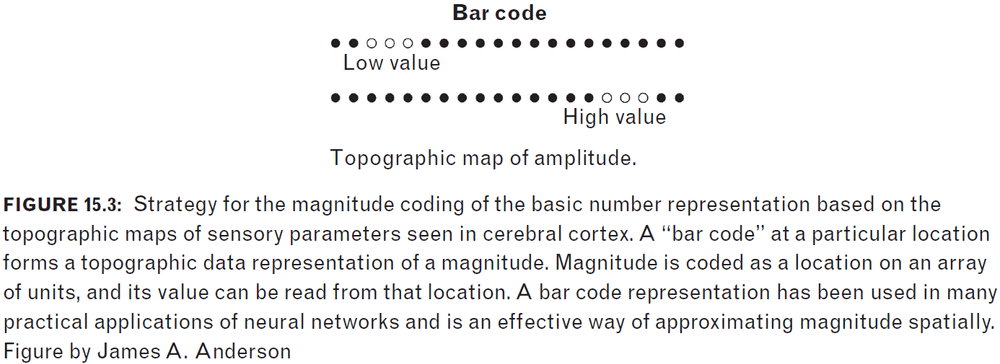

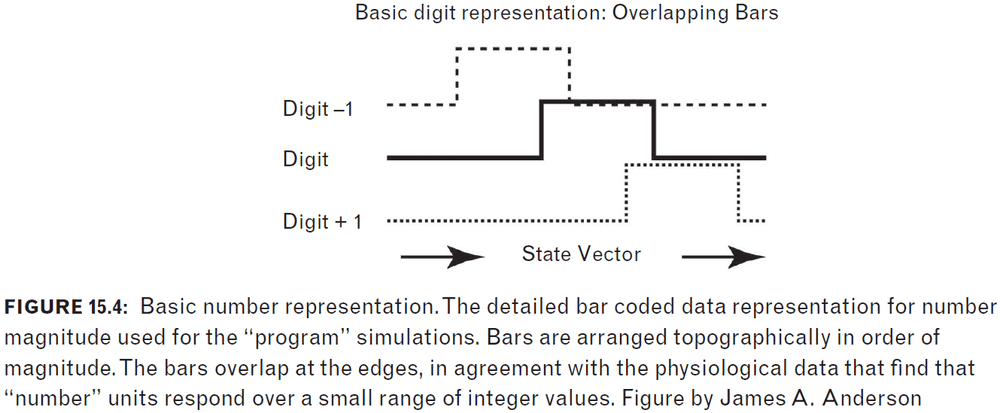

- Numbers seem to be represented on a topopgraphical map just like touch.

- E.g. The number “9” is physically closer to “8” than to “1”.

- Similar magnitude numbers are physically closer to each other which forms a map.

- The location holds value and meaning.

- Human performance for multiplication is always close to the correct answer.

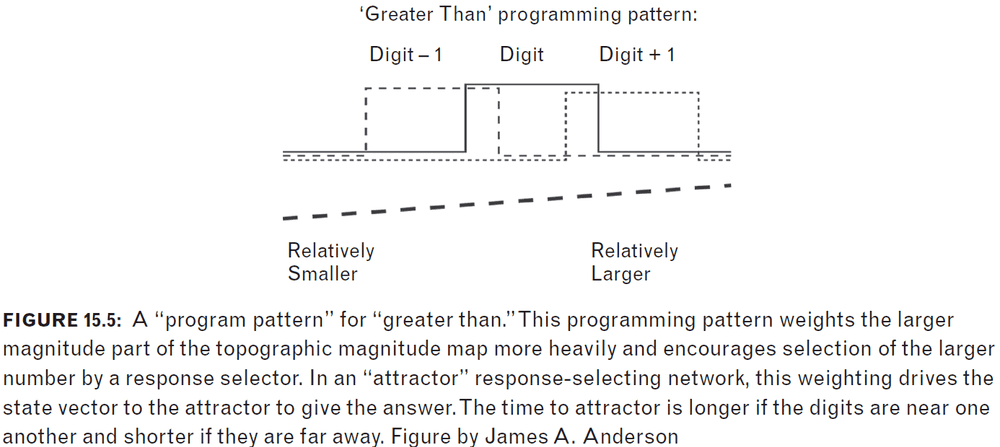

- How can we reverse engineer the way people do number comparisons?

- We first start with how to represent/encode the numbers.

- The second step is to create a program to combine our representations of numbers into the meaningful output that we want.

- When people compare numbers, they only have to remember the single digit comparisons as that can be applied to longer numbers.

- E.g. To determine which number is greater, 100 or 140, we only have to compare the middle digit where 4 is greater than 0.

- It’s paradoxical that the larger the difference, the faster the answer because shouldn’t things farther away take longer?

Chapter 16: Return to Cognitive Science

- This chapter deals with language ambiguity.

- How to determine which of the many possible meanings a word conveys is important for understanding.

- Disambiguation: how to choose the best-fitted meaning for an ambiguous word.

- Context usually determines which of the meanings of the word to be understood.

- Also known as connotation.

- Experiments suggest that when a word is first seen, all meanings are briefly present but then filtered using disambiguation.

- This happens extremely quickly that the user doesn’t notice.

- Ambiguity also shows up in vision as is known as multi-stable perception.

- The meaning of a word is its use in the language.

- Disambiguation depends on our extensive real-world knowledge.

- Catastrophic unlearning: where learning a new association causes older associations to vanish.

- It’s easier for me to tell you whether a certain book is one in my library than to tell you all of the books in my library. Why?

- It’s easier for me to check than to recall and retrieve.

- In general, the more you know about what you are looking for, the easier it’s to find.

Chapter 17: Loose Ends: Biological Intelligence

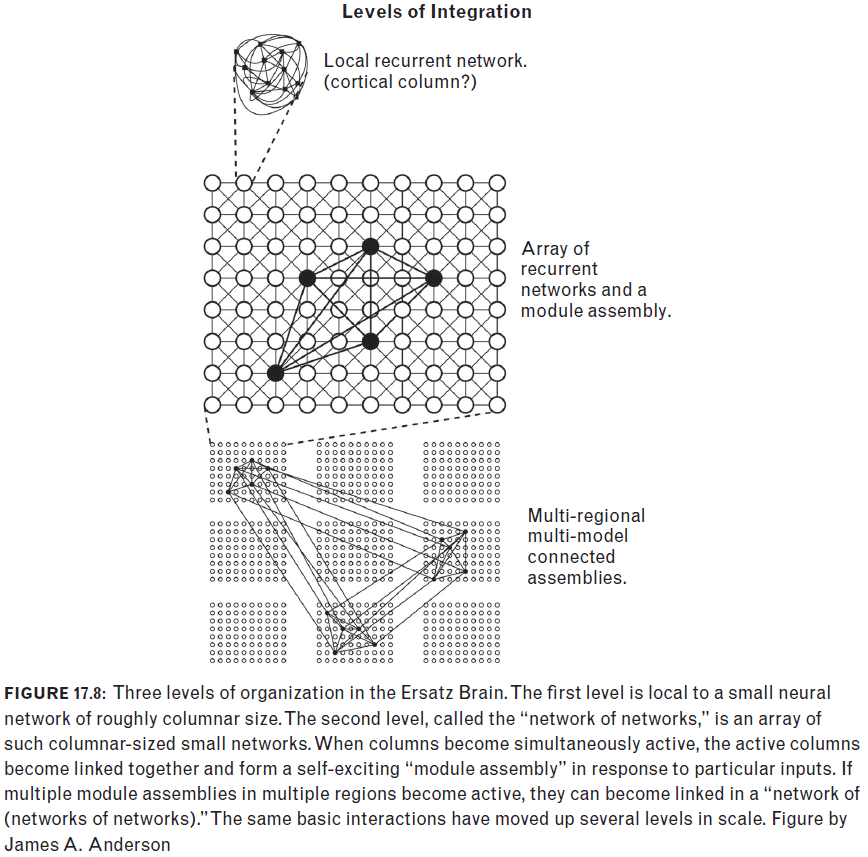

- How does the brain produce cognition?

- Don’t forget about the cognitive science experiments on human response time.

- What happens in the intermediate levels of neuronal organization? Between single neurons and areas of the brain?

- Maybe the neuron isn’t the fundamental computational unit of the brain, maybe it’s the cortical column.

- Distributed sparse representations.

- The farther apart two places are, the longer it takes to travel. Conversion from space to time.

- Time matters in the brain.

- Not everything connects to everything.

- Cells in the higher levels of the visual system have much less spontaneous activity than in the lower regions.

- Stabilize neurons through

- Inhibition

- Negative feedback loops

- Maximum neuronal firing rate

- Letting the voltage not reach the threshold potential

- Increase the distance to let the potential dissipate

- Hebbian synaptic learning probably occurs at the lowest level of organization, but what about the higher levels?

- It’s theorized that larger assemblies can be more stable because of the extensive connections.

- “The secret of a good memory is thus the secret of forming diverse and multiple associations with every fact we care to retain.” Think back to the Russian reporter and the memory palace.

Chapter 18: The Near Future

- The computer could calculate any logical function, a universal device, it could become anything but was in itself nothing.

- Computers aren’t fault tolerant. If one bit changes, the entire program changes.

Chapter 19: Apotheosis: Yes! Or No?

- Three types of computers

- Digital

- Analog

- Brain-like

- Brains are between digital and analog. It’s like analog because of how specialized the hardware is but it’s like digital because of how generalized the software is.

- The flexibility from learning and association.