Neuroscience Papers Set 5

By Brian PhoFebruary 15, 2022 ⋅ 69 min read ⋅ Papers

Recent Advances in Electrical Neural Interface Engineering: Minimal Invasiveness, Longevity, and Scalability

- This paper reviews some of the latest progress in electrical neural interfaces, emphasizing advances in the spatiotemporal resolution, and extent of mapping and manipulating brain circuits.

- First, we cover electrode design and strategies for long-term and large-scale recordings.

- Second, we address the need for electronics to be custom designed for wireless, bidirectional transfer of data and power to the device.

- Third, we outline how the combination of electrical and optical methods widens possibilities to address the demands of spatiotemporal scale.

- Finally, we elaborate on the analytical methods to extract features from large-scale electrical recordings.

- Three challenges to electrical neural interface design

- Spatial scale

- Neural circuits span wide spatial scales in the brain.

- E.g. From neurons to neuron clusters to brain regions.

- On the microscale, we need high spatial resolution in 3D to capture local information processing due to the density of synaptic connections (3000-10000).

- On the macroscale, we need large and distributed coverage to detect neural dynamics at high resolution across multiple regions.

- Temporal scale

- Neural activity occurs across broad time scales in the brain.

- E.g. Synaptic strength (seconds), circuit remodeling (days to months), development and degeneration (years).

- Anatomical diversity

- Brain structure and organization is remarkably different across species and individuals.

- Functionally distinct brain regions have unique anatomical organization.

- E.g. Tissue geometry, cell types, cell density, cell shape and complexity.

- Spatial scale

- Intracortical electrode design

- Implanted electrodes enable the detection of individual neurons at high temporal resolution in living brains.

- The recording sites transduce signals from the current flow through the extracellular space during the propagation of action potentials (APs), providing enough high temporal resolution to resolve the activity of individual neurons near the electrode.

- Classic intracortical electrodes often face difficulties to record high quality neural signals over both short and long timescales.

- Substantial changes in recording conditions are the main culprit.

- E.g. Micro-movements, biotic and abiotic failures, and sustained foreign body reactions.

- Another issue is that brain tissue is soft while most neural electrodes are significantly more rigid, resulting in substantial tissue reactions at the interface between brain tissue and implanted device.

- E.g. Blood brain barrier (BBB) leakage, neuronal degeneration, and glial scaring.

- We can work around this problem by making neural probes with features that more closely resemble those of their biological host.

- E.g. Reducing microwire diameter from 50-75 mm to 15 mm reduced neuronal cell death and glial scarring.

- Alongside the development of miniaturized intracortical electrodes, increasing effort has been made to develop flexible electrodes.

- However, these materials are still 6-7 orders of magnitude stiffer than brain tissue, so the mismatch between brain and electrode remains significant.

- A key issue is that materials that are as soft as brain tissue typically don’t have the necessary properties to function as an electrode such as electrical insulation and mechanical strength.

- A series of studies fabricated neural electrodes at 1 micrometre, which provided ultra-flexibility and seamless integration with the host tissue.

- Intracortical electrodes can only detect and distinguish activity of nearby neurons, therefore, to record from large populations of neurons, we need to implant a large array of electrodes.

- This risks tissue displacement and injury.

- Three directions to develop high-density neural electrodes

- Reduce device footprint.

- Improve microfabrication of high-density, highly integrated silicon neural probes.

- Pattern high-density contact arrays on flexible substrates.

- The need for neural electrodes to

- Flexibly distribute large numbers of recording sites to target both local and distributed circuits,

- Minimally disrupt the integrity of neural tissue, and

- Track activity across timescales ranging from seconds, months, or years,

- Has fueled the exciting development of a variety of novel neural electrodes in recent years.

- As yet, no single device meets all of these requirements.

- Power, Data, and Communication

- Advances in electrodes must accompany advances in wireless power and data transfer between the implanted device and a local transmitter/receiver.

- While we can transfer power and data through wires, this results in limited movement and opens paths for infection.

- These challenges have led researchers to look for options to transfer power and data to and from neural implants wirelessly.

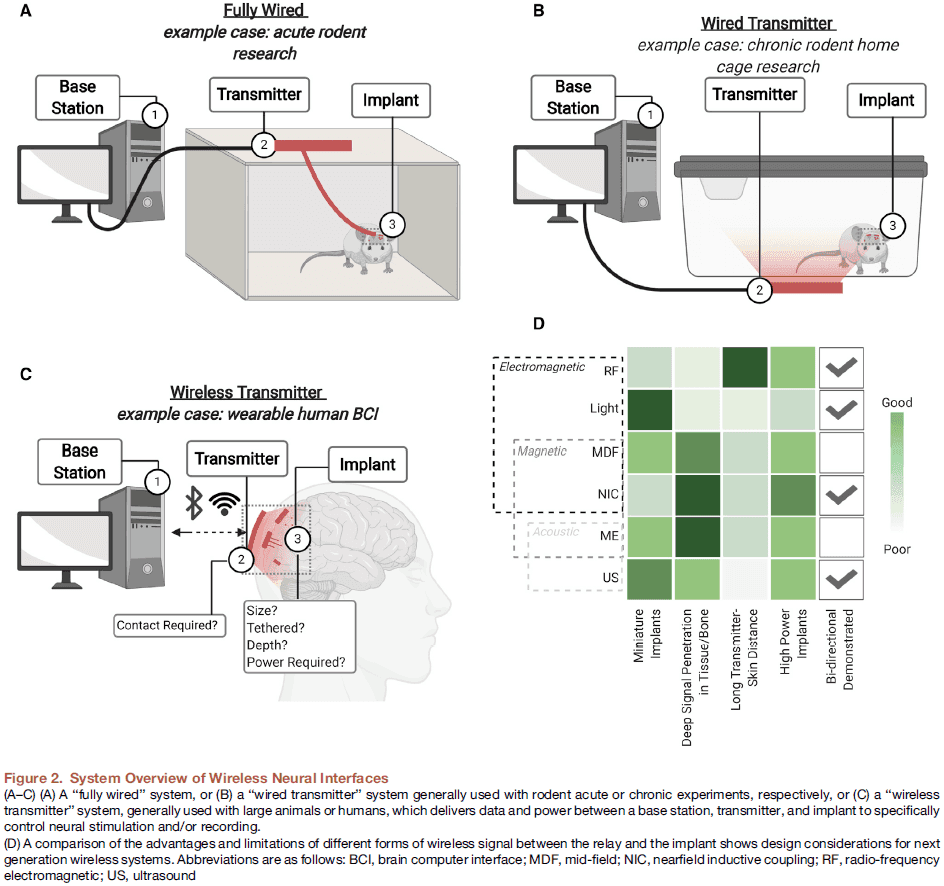

- Three major components of transmitting wireless data and power

- A base station that processes data and determines the appropriate stimuli to be delivered.

- A transmitter that communicates with the implant and the base station.

- A neural implant that interfaces directly with the target tissue to stimulate or record neural activity.

- While the link between the base station and transmitter may be wired or wireless, a significant challenge is the link between the transmitter and implant.

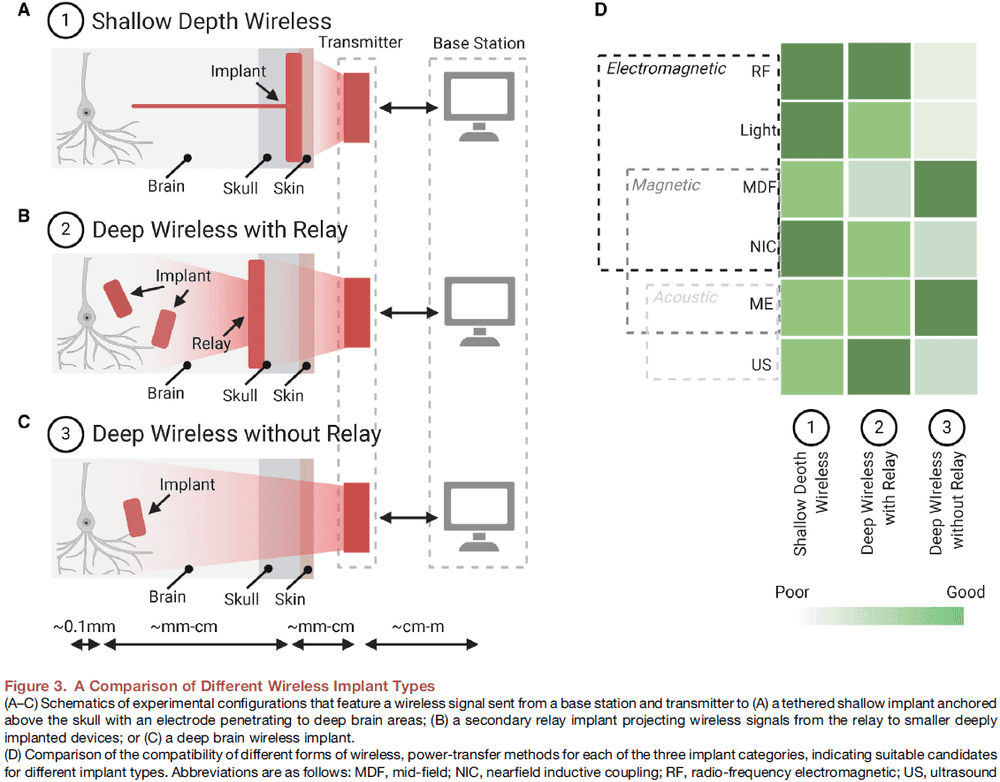

- Three different wireless communication techniques

- Electromagnetic

- Magnetic

- Acoustic

- Tissue absorption of the electromagnetic wireless signal is a specific challenge in the link between transmitter and implant.

- Magnetic fields at 13 MHz suffer little tissue absorption but the power gathered depends on the coil area and alignment with the transducer.

- Ultrasound (US, 1.85 MHz) has emerged as an alternative for wireless power transfer using safe levels of pressure waves to deliver power to a small implanted piezoelectric crystal.

- US can be used to transfer data back using the reflection of ultrasound waves that travel back to the US transmitter/receiver.

- However, one issue with US is that it needs to be in direct contact with the body using impedance matching gels or foams.

- The use and combination of these different power-transfer techniques lead to three general classes of wireless implants with different degrees of invasiveness.

- A shallow wireless link between a transmitter on the scalp and a receiver below the skin.

- A deep wireless link to subcortical device via a relay implanted beneath the skull.

- A deep wireless link directly between a transmitter on the scalp and subcortical implant.

- Electronics for Neural Interfaces

- Five building blocks

- Amplifier

- Filter

- Analog-to-digital converter (ADC)

- Stimulator

- Communication interface

- Typical neuronal signals are weak, ranging from tens of millivolts to several microvolts, and thus require amplification.

- Depending on the signal of interest, field potentials or action potentials, spectral filtering is often necessary to reject interference and noise outside of the desired frequency band.

- Computers can only process and store digital information so an ADC is used to convert from analog neuronal waveforms into binary digital streams.

- Neurons can be stimulated using current or voltage pulses, which are generated by a programmable stimulator.

- Two classes of neural interfaces

- Brain-machine interfaces (BMI) require a high channel count and fine spatiotemporal resolution to enable large-scale and high-density monitoring of neural activities. The design emphasizes low power consumption and a small footprint.

- Miniaturized neural implants for recording and stimulation of a small region of the nervous system typically requires fewer channels compared to a BMI but prefers untethered operation.

- Despite the many benefits provided by digitizing recorded signals, ADCs come with high power consumption.

- Five building blocks

- Bi-modal Electrical-Optical Neural Interfaces

- Skipping over this section due to disinterest.

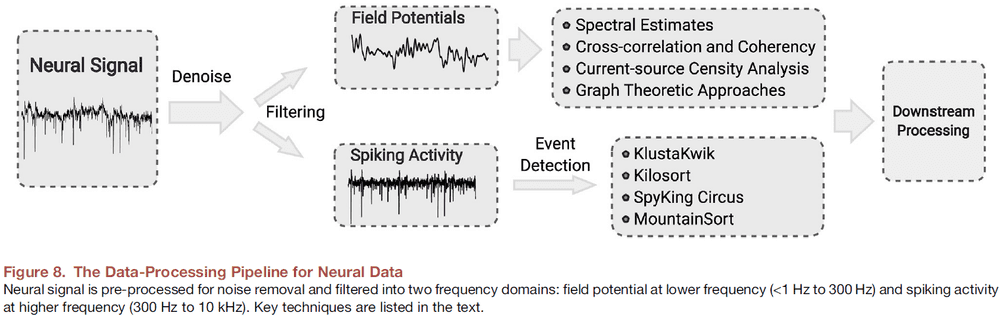

- Neural Data Processing

- Broadband signals acquired by neural interfaces generally have two types of voltage signals.

- The high-frequency spikes (300 Hz to 10 kHz) are the extracellular APs generated by individual neurons as measured by intracortical microelectrodes.

- The low-frequency field potentials (<1 Hz to 300 Hz) derive from a population of neurons in a small volume of tissue.

- Spike sorting: the process of detecting spiking events and assigning different spike waveforms to neurons.

- Preprocessing is done on the signal to ensure that it doesn’t covary due to non-biological confounds such as electrical cross-coupling, line noise, or artificial splitting.

- Two remaining challenges

- Overlapping spikes

- Drift

- Importantly, depending on the goal or question, spike sorting can be skipped altogether by instead using multi-unit threshold crossings to estimate low-dimensional neural population dynamics.

- Extracellular field potentials reflect the activity of a population of neurons and are called electroencephalograms (EEG) when measured at the scalp, electrocorticogram (ECoG) when measured with subdural grid electrodes, and local field potentials (LFP) when measured using invasive electrodes.

- In recent years, electrical neural interfaces have been developed to support the interrogation of highly complex brain circuits that can involve vast numbers of neurons at diverse spatiotemporal scales.

- This review discussed exciting advances in multiple areas of electrical neural interface development such as the design of neural electrodes, novel mechanisms that permit wireless interfaces, specialized ASICs, integration of electrical interfaces with optical methods, and the creation of algorithms to extract features from neural recordings.

- The application of these advances has improved our capability to interact with the nervous system.

Compromise of Auditory Cortical Tuning and Topography after Cross-Modal Invasion by Visual Inputs

- Brain damage can induce reorganization of sensory maps in cerebral cortex.

- Previous research has focused primarily on adaptive plasticity within the affected modality, but less focus has been given to maladaptive plasticity that may arise as a result of invasion from other modalities.

- Changes in sensory input can result in plastic changes to sensory pathways.

- Although cross-modal (XM) plasticity is a common outcome of sensory loss, it has received less study than unimodal plasticity.

- One reason to study XM plasticity is for optimizing rehabilitation.

- We previously found that the auditory cortex (AC) of ferrets after unilateral neonatal midbrain damage contains neurons that respond to a single modality (auditory and visual neurons) and to both modalities (bisensory neurons).

- Because these different response types are distributed randomly within cross-modal auditory cortex (XMAC) rather than in a segregated manner, communication between unimodal neurons might be disrupted by neighboring XM neurons.

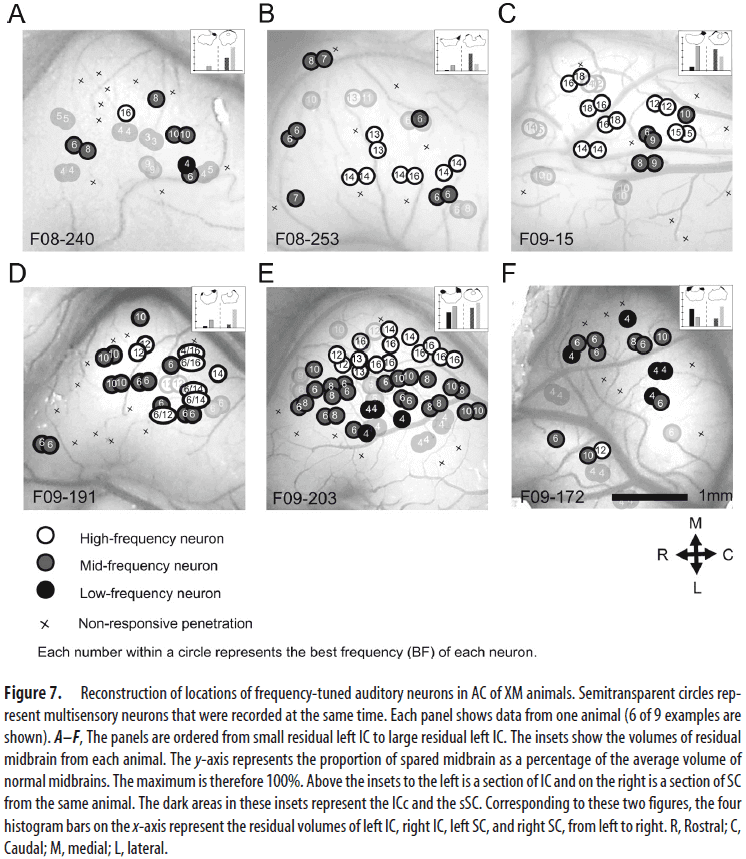

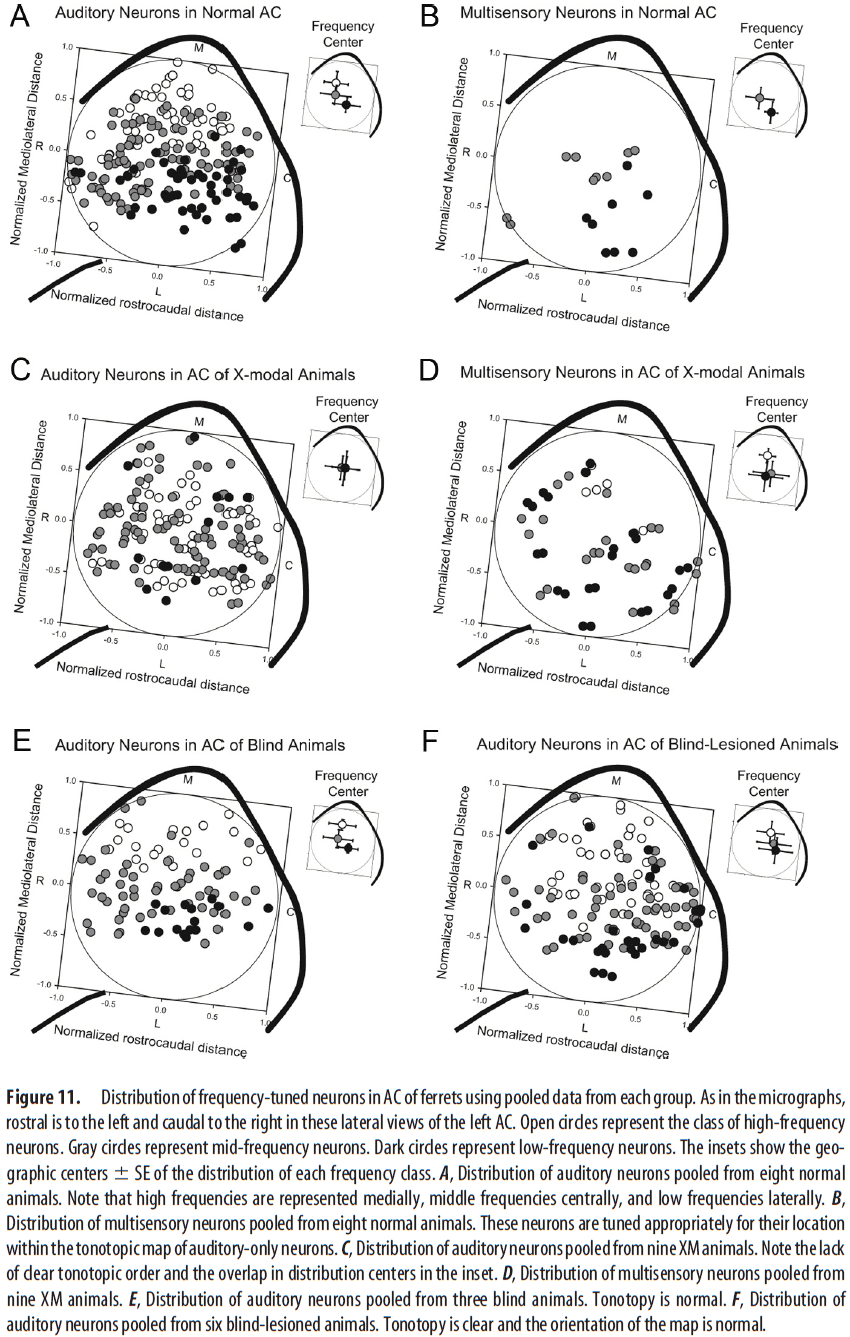

- This paper tests whether competition from visual inputs compromises auditory tuning and topography in XMAC using in vivo single-unit recordings in anesthetized ferrets.

- We found that auditory tuning and tonotopic mapping in auditory cortex are impaired after XM plasticity.

- These results provide support for the hypothesis that competition between auditory and visual inputs after XM plasticity underlies the compromised auditory function in patients with partial hearing loss, and it also explains why blind humans often have improved auditory function.

- Skipping over materials and methods section.

- We’re interested in whether residual auditory function is compromised by invasion of visual inputs. Because damage to both auditory and visual midbrain is necessary to induce XM plasticity, it’s important to establish whether AC function was impaired by anomalous visual inputs, loss of auditory inputs, or both.

- Are the changes in XMAC caused by auditory deafferentation or by visual activation?

- To separate these possibilities, we designed a blind-lesioned group that had the same neonatal midbrain lesions as XM animals but no visual inputs as a control for the effect of visual activation of XMAC.

- Thus, the study contained four groups

- Normal

- Cross-modal (XM)

- Blind-lesioned

- Blind

- Findings

- Residual midbrain volume of XM animals wasn’t significantly different from the residual midbrain volume of blind-lesioned animals.

- Auditory and multisensory neurons in AC of XM animals were tuned to pure tones.

- Visual inputs affect the threshold of auditory and multisensory cortical neurons to sound.

- Auditory neurons in AC of XM animals had broader tuning to sound frequency than auditory neurons in normal AC.

- Multisensory neurons in AC of XM animals had a longer latency response to sound stimuli than unisensory auditory neurons in either normal AC or XMAC.

- Neurons in XMAC and AC of blind-lesioned animals retain selectivity for sound frequency despite the significant early damage to the auditory midbrain (inferior colliculus).

- The tonotopic organization of auditory and multisensory neurons was altered by XM plasticity.

- High-, mid-, and low-frequency auditory neurons in XMAC were scattered rather than being arrayed along the mediolateral axis as seen in normal animals.

- This suggests that auditory tonotopy was severely disrupted by the visual invasion into AC of XM animals.

- Visual inputs lead to a disrupted topography of frequency-tuned neurons in XMAC.

- The frequency distribution of tuned neurons wasn’t changed by XM plasticity.

- We found considerable auditory functions in XMAC in that most neurons respond to sound and have a preferred frequency.

- However, the sensitivity to sound, the sharpness of tuning, and the organization of the tonotopic map in XMAC are impaired.

- Results from the blind-lesioned control group show that it’s the anomalous visual input to auditory cortex, and not simply deafferentation of the auditory pathway, that’s responsible for the impairment of auditory function.

- This suggests that loss of input to auditory thalamus can be compensated for during recovery.

- In the blind group, the auditory map was normal but the sensitivity of auditory neurons to sound was increased, suggesting that visual impairment can boost auditory processing ability as also seen in blind humans.

- As in patients who can perceive their amputated limb after surgery, tinnitus patients may hear phantom tones in a quiet environment.

- Thus, phantom limb syndrome and tinnitus may both be triggered by XM inputs. The same goes for synesthesia.

- It’s possible that auditory neurons receiving direct thalamocortical auditory input are less likely to receive XM visual inputs. The competition between afferents may push visual afferents to innervate neurons that receive corticocortical auditory connections, giving those neurons longer auditory latencies.

- Multipeaked auditory neurons appear in XM and blind-lesioned animals that had more than one best frequency, creating multiple peaks in their tuning curves.

- The creation of multipeaked tuning curves in XMAC implies that auditory neurons in XMAC have lost considerable frequency specificity as a result of the loss of some auditory input and gain of visual input.

- Basic auditory cortical response properties in the inferior-colliculus-lesioned blind animals are essentially intact, independent of any contribution from the visual pathway, suggesting that compensatory plasticity can substantially rebuild auditory function after deafferentation.

- In conclusion, these findings provide additional evidence that, although the auditory cortex can recover from neonatal deafferentation in some respects, its function is impaired by ectopic XM visual inputs, suggesting that minimization of XM activity may improve the chances of a successful outcome in patients with lost sensory input.

All brains are made of this: a fundamental building block of brain matter with matching neuronal and glial masses

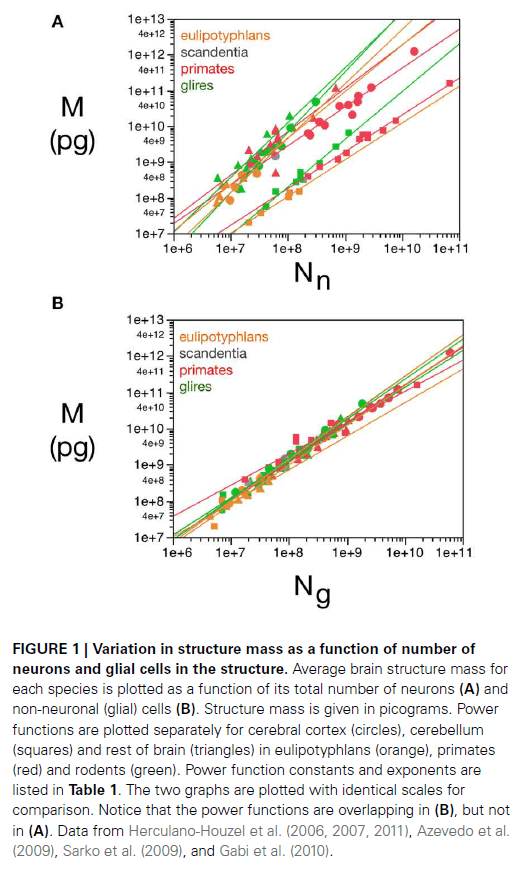

- How does the size of neuronal and glial cells that compose brain tissue vary across brain structures and species?

- Previous studies have found that average neuronal size is highly variable while average glial cell size is more constant.

- E.g. Average neuron mass varies by over 500-fold across brain structures and species, while glial cell mass varies only by 1.4-fold.

- Two fundamental and universal relationships apply across all brain structures and species

- The glia/neuron ratio varies with the total neuronal mass in the tissue.

- The neuronal mass per glial cell varies with average glial cell mass in the tissue.

- We propose that there’s a fundamental building block of brain tissue: the glial mass that accompanies a unit of neuronal mass.

- We argue that the scaling of this glial mass is a consequence of a universal mechanism where numbers of glial cells are added during development, regardless of whether the neurons composing it are large or small, but depend on the average mass of the glial cells being added.

- Brain tissue is composed of three cell types

- Neuronal

- Glial

- Endothelial

- There must be biological rules that determine the number of cells of each type but little is known about such rules.

- Neurons are the smallest separable units of information processing in brains.

- The development of the isotropic fractionator made feasible the precise measurement of total number of neuronal and non-neuronal cells in brain structures.

- All cell numbers were obtained using the same method of isotropic fractionator.

- For simplicity’s sake, we will now refer to non-neuronal cells as “glial” cells with the understanding that our model ignores an estimated 2-4% of brain volume occupied by vasculature.

- While different neuronal scaling exponents apply to different structures and different mammalian orders, similar glial scaling exponents apply across structures, species, and orders.

- This suggests that the average neuronal mass differs across structures, species, and orders, but that the average glial cell mass is mostly invariant for each structure, species, and order.

- Skipping over the math of the paper.

- Average neuronal cell mass in a structure increases with the number of neurons in the rodent brain, while no correlation is found for any structure across primate species.

- The glia/neuron (G/N) ratio in any brain structure depends simply on the average size of the neurons in that structure.

- The total glial mass in a structure is added in a similar way to all brain structures in all species that matches precisely the total neuronal mass in that structure at a certain ratio.

- In other words: For every unit amount of neuronal mass, there’s a matching unit amount of glial mass in a predictable manner.

- Results suggest that numbers of glial cells are added to match the total neuronal mass in the tissue.

- The quantitative match between the total glial mass in a structure and the total neuronal mass can be thought of as a fundamental building block of brain tissue across species and orders where a certain amount of neuronal matter is assigned to each glial cell (or vice-versa).

- Neuronal cell size varies tremendously across brain structures and species but in contrast, average glial cell size varies only modestly.

- These estimates are consistent with the enormous diversity of neuronal cell types compared to the modest diversity of glial cell types.

- We propose that the relationship between the G/N ratio and average neuronal cell mass is a universal property of any brain tissue.

- Our model shows that all brain structures analyzed are mostly neuronal in their mass, with a neuronal mass fraction that ranges between 60-80%, while glial mass fraction ranges between 40-20% respectively.

- Individual glial cells provide functional support to an amount of neuronal tissue that varies in mass from just slightly more than the glial cell itself up to a few times it own mass.

- The neuronal mass supported by each glial cell is a universal function of average glial cell size across brain structures and species.

- There appears to be universal mechanisms that determine

- The amount of neuronal tissue that’s taken care of by each glial cell, which depends on small variations in average glial cell mass.

- The G/N ratio, which depends on large variations in average neuronal cell mass.

- The relationship we describe here indicates an upper limit to how much neuronal mass a single glial cell can support, which makes physiological sense.

- This also implies that brain tissue, regardless of the structure, is constructed in a way that’s limited by the extent of support that each glial cell can provide to neurons in the area, which in turn, depends on the average mass of individual glial cells.

- The shared glial scaling rules are evidence that while neurons have been mostly free to vary in morphology and physiology during evolution, there’s strong selective pressures that must have kept glial cell variability to a minimum such that only a few different astrocyte and oligodendrocyte types are recognized.

- Such strong selective pressure against glial cell variability implies that the functions exerted by these cells are so fundamental for brain physiology that they can’t really be modified without compromising brain viability and the survival of the individual.

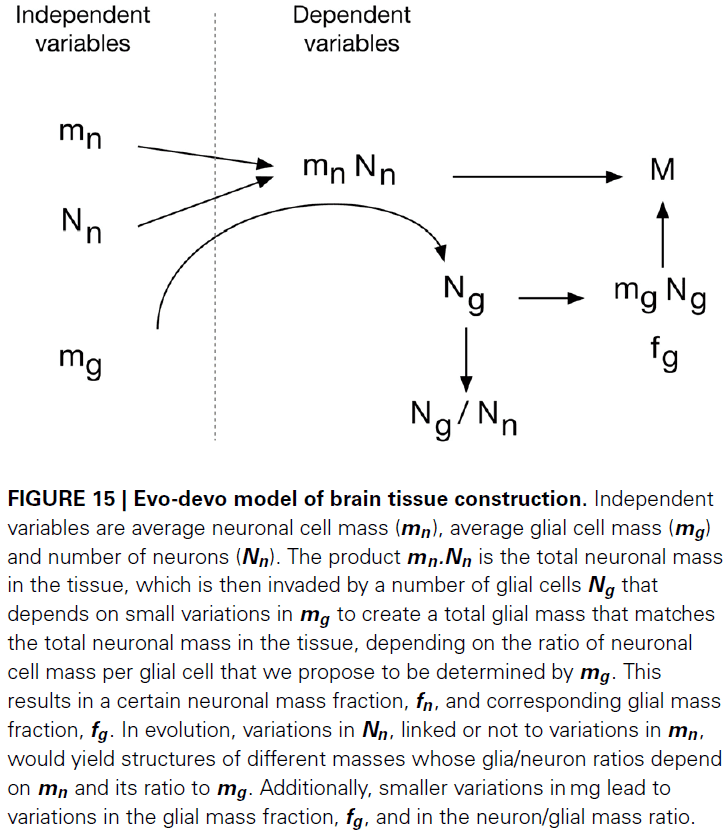

- Only three variables are necessary to determine the cellular composition and final mass of any mammalian brain structure.

- Average glial cell mass

- Average neuronal cell mass

- Number of neurons

- From these three variables, all other cellular properties of the tissue are derived.

- The evolutionary developmental model of brain construction that we propose is based on the fact that brain parenchyma is initially almost entirely neuronal in development.

- Number of neurons + Pre-determined average neuron size → Total neuronal mass.

- This neuronal mass is invaded by glial cell precursors, which then generate glial cells of a predetermined average size and in a number that depends on their average size.

- We propose that the matching of total glial to total neuronal mass is the mechanism that determines the total number of glial cells that will compose the tissue.

- Therefore, the ratio between glia/neuron numbers is simply a result of this matching of glial to neuronal mass in the tissue, yielding a glia/neuron ratio that varies with average neuronal cell mass but depends more precise on the ratio of average neuronal to glial cell mass.

- It seems likely that the total glial mass in the tissue is matched to the total neuronal mass simply by the regulation of glial progenitor proliferation.

- We propose that the universal relationship between the amount of glial mass that accompanies a unit of neuronal mass, which we call the fundamental building block of brain tissue, is a consequence of a universal mechanism whereby numbers of glial cells are added to the neuronal parenchyma during development, irrespective of whether the neurons composing it are large or small, but depends on the average mass of the glial cells being added.

Cortical mechanisms of colour vision

- Color is important because it facilitates object perception and recognition.

- Despite the long history of studying color vision, we still have much to learn about the physiological basis of colour perception.

- Studies are starting to indicate that color isn’t processed in isolation, but together with information about luminance and visual form by the same neural circuits to achieve a unitary and robust representation of the visual world.

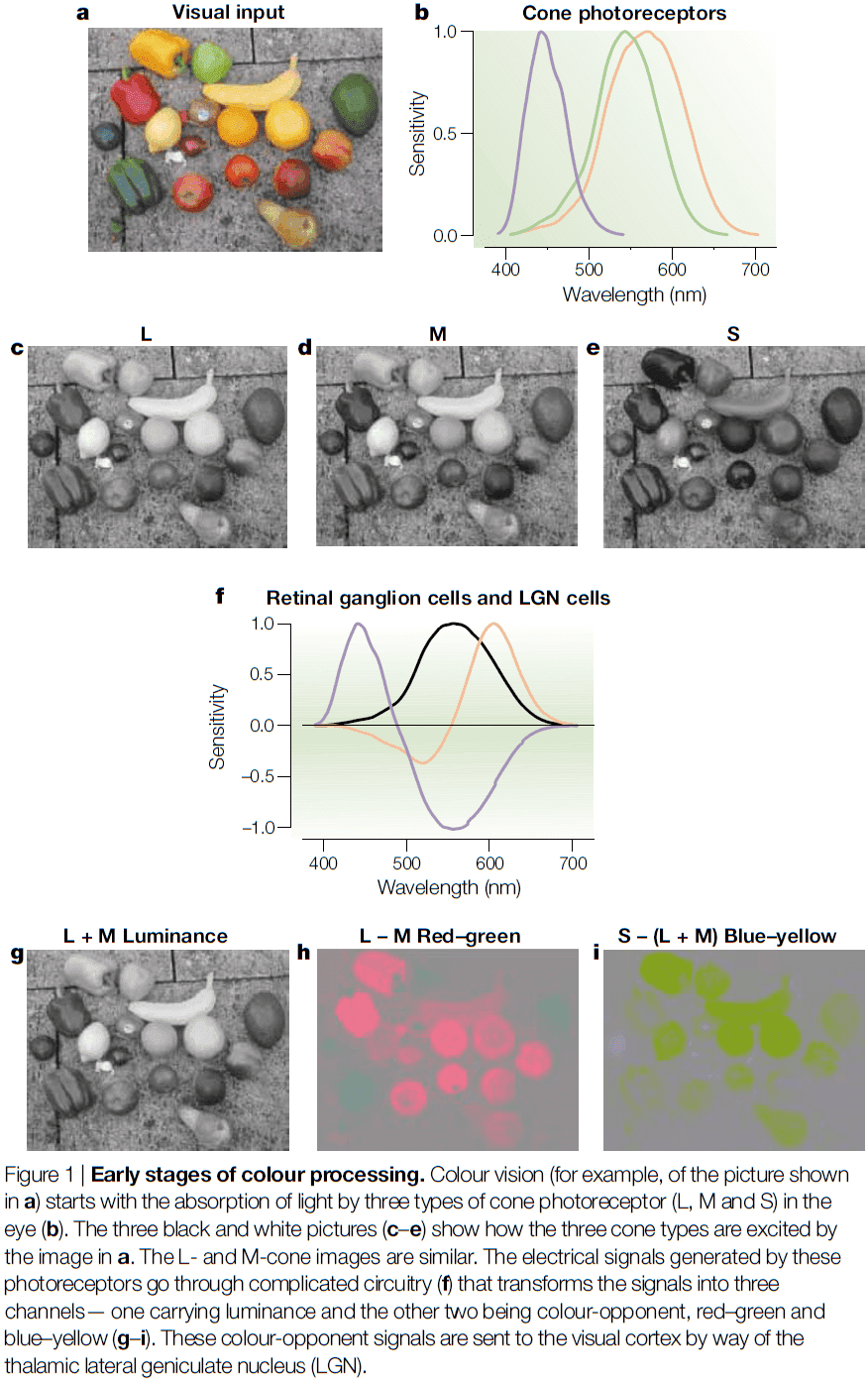

- Rods and short-wavelength (S)-cones are phylogenetically older, the long- (L) and middle- (M) wavelength cones evolved from a common ancestral pigment only about 35 million years ago, probably for the benefit of an improved diet of ripe red fruit rather than for green leaves.

- Trichromacy implies that the effect of any light on the visual system can be described by three numbers: the excitation it produces in the L-, M-, and S-cones.

- Cones act like photon counters where information about the wavelength of each individual photon is lost to each photoreceptor, but is instead captured by the type of receptor.

- For each cone, information about wavelength and intensity are confounded/mixed.

- At the next stage of processing, the visual system compares the signals from the different cones to compute the color of objects.

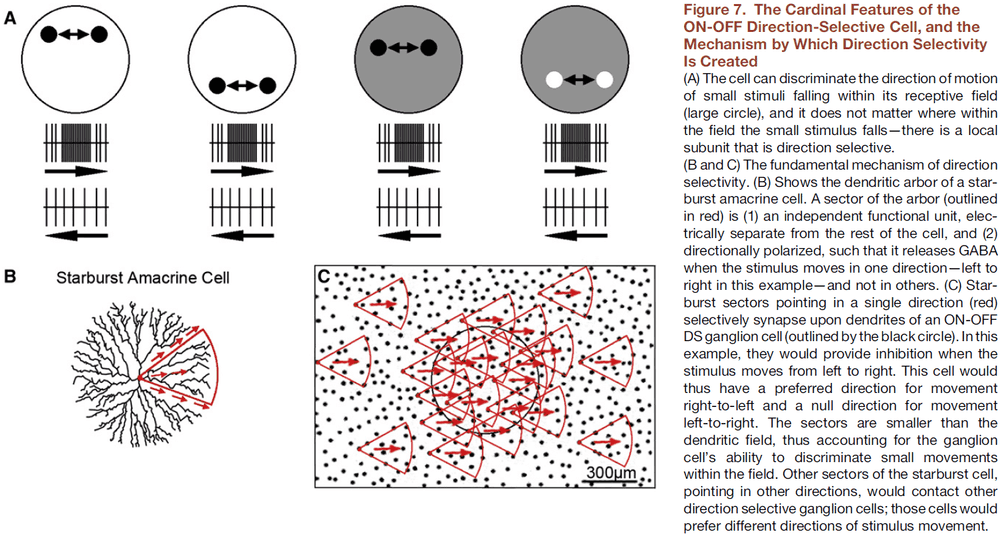

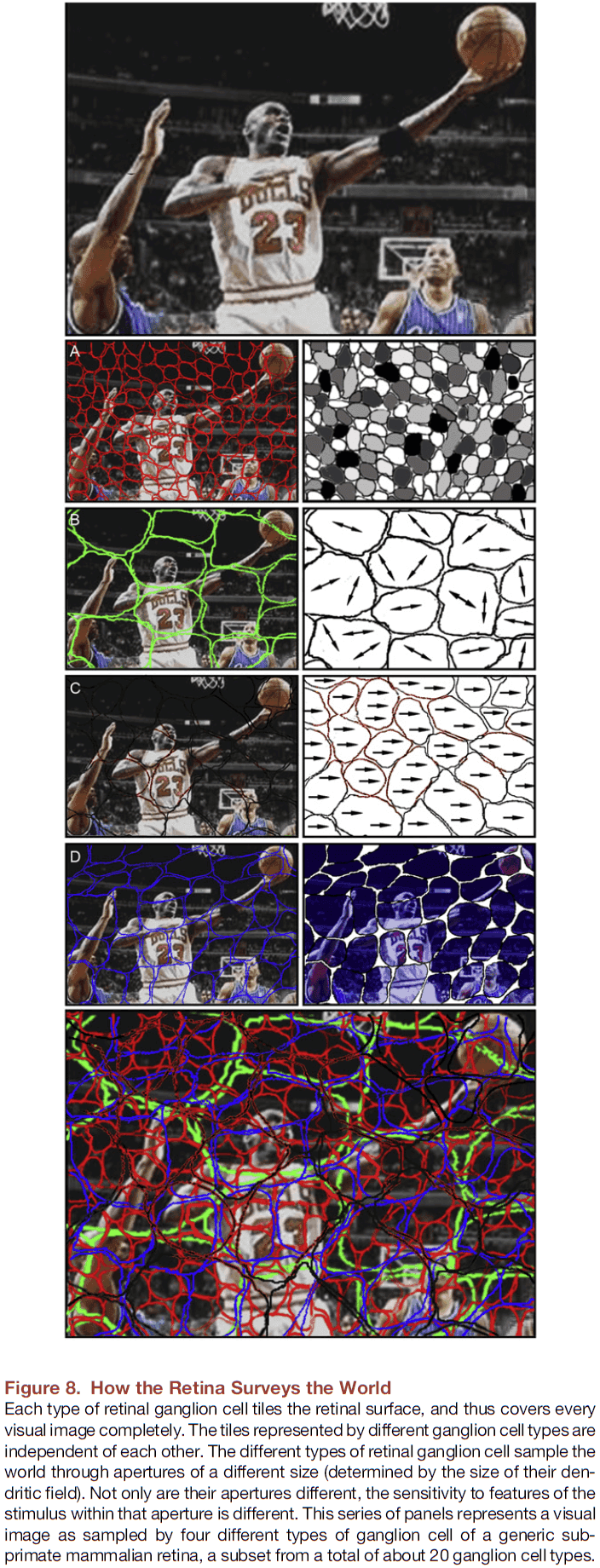

- In the retinal ganglion cells, three channels convey information from the eye to the brain

- L+M or luminance channel: signals from L- and M-cones are added to compute the intensity of a stimulus.

- L-M color-opponent channel: signals from L- and M-cones are subtracted from each other to compute the red-green component of a stimulus.

- S-(L+M) channel: the sum of L- and M-cone signals is subtracted from the S-cone to compute the blue-yellow component of a stimulus.

- Thus, ganglion cells transform raw cone signals into color-opponent signals.

- These three color-opponent signals or channels, the cardinal directions of color space, are functionally independent and are transmitted in anatomically distinct retino-geniculo-cortical pathways.

- E.g. Cells in the magnocellular layers of the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) are mostly sensitive to luminance information, cells in the parvocellular layers are mostly sensitive to red-green information, and cells in the koniocellular layer are mostly sensitive to blue-yellow information.

- Color opponency is computationally important because it removes the inherently high correlations in the signals of the different cone types.

- Most low-level visual functions depend heavily on the magnitude of the input signal as nearly all neurons in the visual system give faster and stronger responses to stimuli of higher contrast.

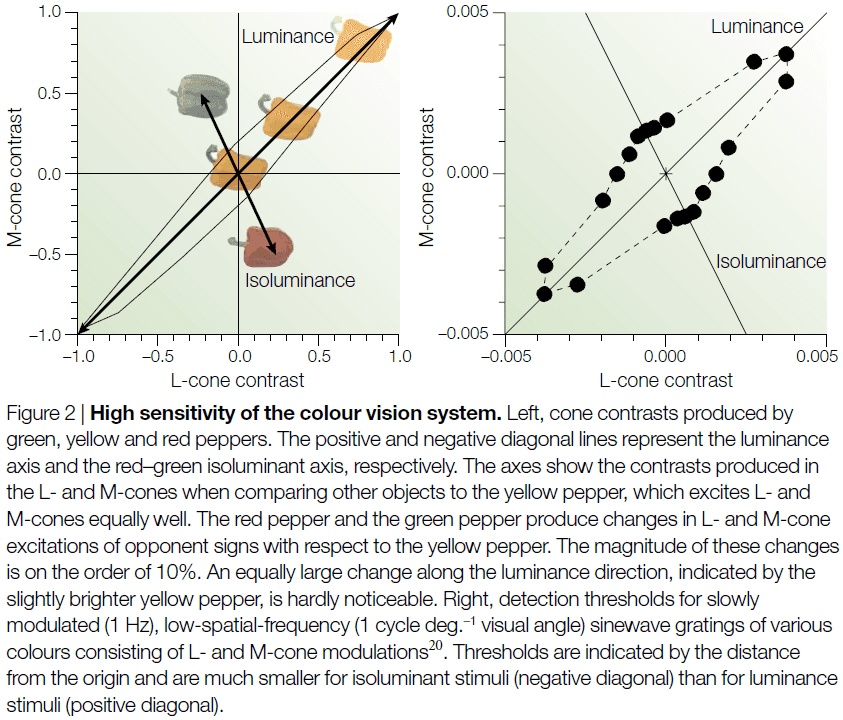

- In addition to working as well as the luminance system in many tasks, the color vision system excels at visual detection.

- E.g. Picking out red spots of light on a neutral gray background.

- Although small changes in luminance are hardly noticeable, color changes with equally large cone contrasts can appear quite noticeable.

- We can conclude from these experiments that color is what the eye sees best.

- Why did trichromatic color vision evolve?

- One answer is that detecting ripe red fruit against green foliage is improved when using the L-M color-opponent channel.

- However, we also find that color vision significantly improves the speed of object recognition and significantly improves memory for the same scenes.

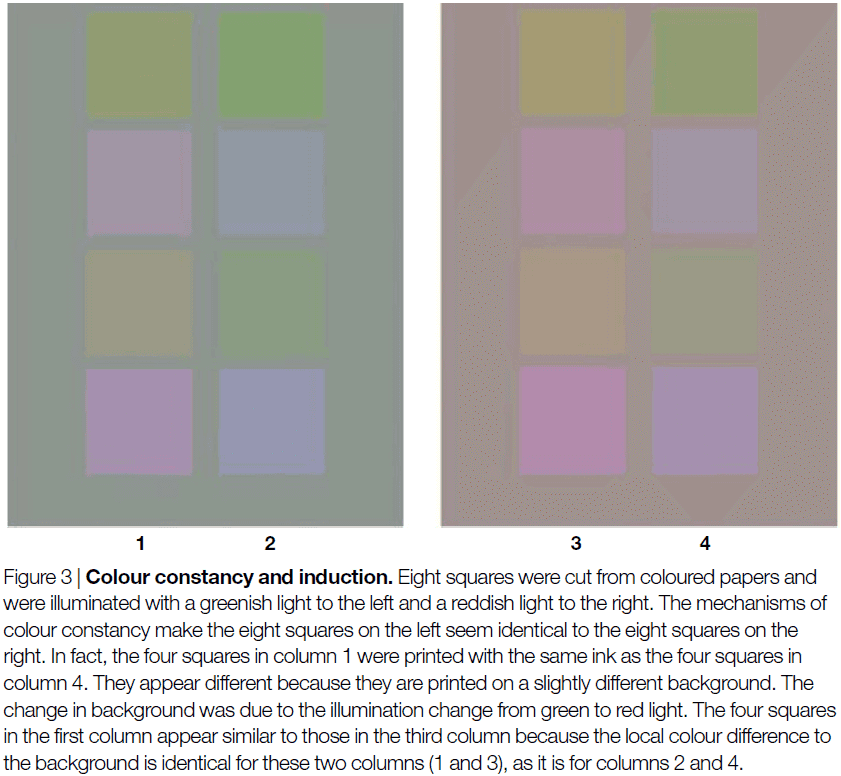

- Chromatic induction: when two stimuli reflect the same spectral distributions of light and lead to the same local pattern of cone excitations, but result in different color percepts.

- On the flip side, different spectral distributions of light can lead to the same color percept, a concept called color constancy.

- Two types of color-selective neuronal responses

- Responses that correlate with the ratios of retinal cone excitations

- Responses that correlate with our percept

- Cells that add L- and M-cone inputs are called luminance cells, and cells that subtract L-, M- or S-cone inputs are called color cells.

- With this definition, many luminance cells would also give different responses to color changes, and many color cells would respond to changes in luminance.

- The proportion of color-selective cells is estimated to be about 50% in the early visual areas of macaque monkeys with little differences between V1, V2, V3, and V4.

- Past studies assumed that there were two distinct subpopulations of cells, one responding only to luminance and the other only to color.

- However, the picture that emerges from many recent studies is that there’s a continuum of cells varying from cells that respond only to luminance to a few cells that don’t respond to luminance at all.

- Thus, results clearly indicate that in the cortex, the analysis of luminance and color isn’t separated.

- In visual cortex, unlike the LGN, the distribution of a cell’s preferred colors doesn’t clearly cluster around particular directions in color space.

- E.g. LGN color-selective cells prefer stimuli along the cardinal red-green or blue-yellow directions. By contrast, cells in the cortex have preferences for many other hues.

- Color can be useful for identification because unlike other visual features, such as shape, colors don’t change under different viewpoints.

- E.g. Rotation and translation don’t change color.

- However, different illumination conditions do change how we view an object.

- Only the proportion of light reflected by the object at each wavelength is an inherent property of each object.

- The visual system has several mechanisms, both retinal and cortical, to discount changes in illumination.

- E.g. Light adaptation in single cones and local contrasts between adjacent cones such as lateral inhibition. Another powerful cue for color constancy seems to be the average color over a large region of the scene.

- Double-opponent cell: a cell that measures the chromatic contrast between centre and surround.

- These double-opponent cells respond best to edges defined by chromatic and luminance differences, which matches the real world as most edges combine both luminance and chromatic differences.

- Double-opponent cells represent a big step towards the neural correlates of color constancy, however, they’re probably only a part of color constancy.

- Is color computed separately from other visual attributes, such as form, motion, or depth, or are these computations carried out simultaneously?

- This question needs to be answered separately for each level of processing.

- Review of the ventral and dorsal visual pathways.

- Segregation hypothesis: the independent processing of visual attributes is maintained between the retinogeniculate pathway and extrastriate cortex.

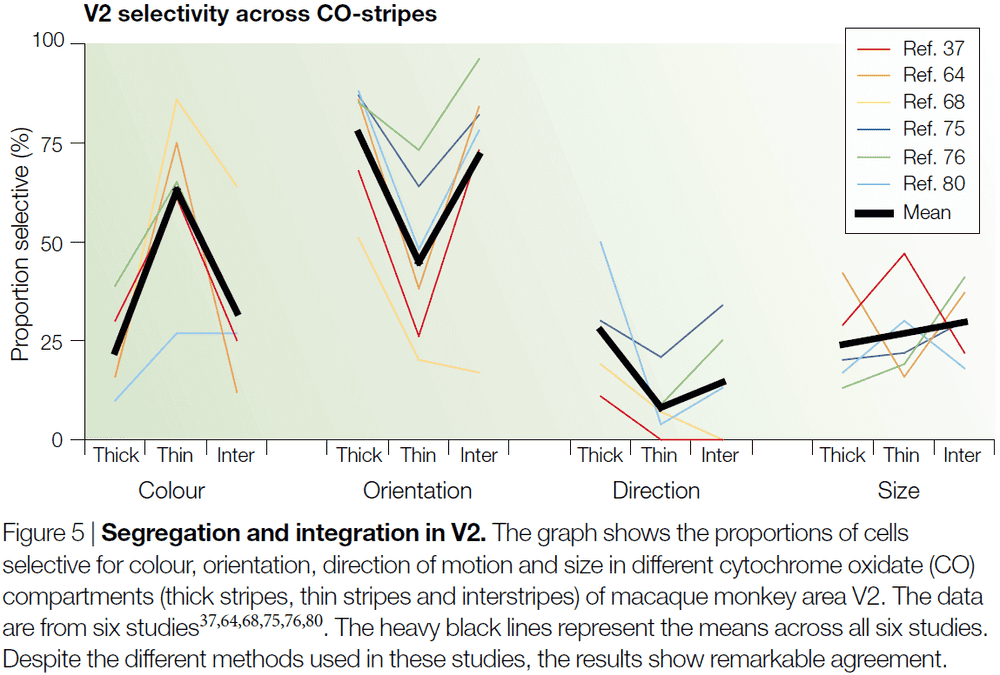

- The anatomical organization revealed by cytochrome oxidase (CO) staining shows that color signals are processed, in V1 and V2, by a population of unoriented neurons located primarily in the CO-rich blobs of V1 and the thin bands of V2.

- For each visual attribute, we don’t find a clear and extreme segregation of attribute to CO-compartment.

- Instead, about 60% colour selectivity is found in cell in the thin stripes and around half of that in the thick strips and interstripes.

- Given that there’s almost complete segregation of colour responses in the LGN, with no color selectivity in magnocellular layers, and that early studies of V1 reported almost complete segregation of the blob and interblob systems, it was assumed that V2 would be the first stage to integrate the different systems.

- However, recent experiments have found that there’s just as little segregation in V1 as there is in V2.

- Is there a ‘color centre’ in the cortex?

- Some patients develop cerebral or acquired achromatopsia after damage to visual cortex.

- This is the case when patients have a specific deficit of color vision with hardly any impairment of form vision.

- If this is the case, then we might expect to find an area of the brain where neurons respond mostly to color, a color centre.

- Color-selective neurons are concentrated in the parvocellular layers of the LGN and lesions to this layer lead to a severe deficit in color vision while most other aspects of vision are intact.

- Interestingly, lesions to the magnocellular system also leave most of vision intact, even functions that are usually associated with that system.

- So is achromatopsia due to damage to the parvocellular layers of the LGN?

- Most human patients with cerebral achromatopsia have lesions in area V4 and while it’s tempting to conclude that this is the color centre of the brain, the situation is much more complicated.

- Despite the large number of patients studied, there’s no well documented case of cerebral achromatopsia without any other visual defects.

- Area V4, both in monkeys and in humans, isn’t only responsible for color vision, but is also important for all aspects of spatial vision and integrates vision, attention, and cognition.

- We can say with certainty that V4 is important for color vision, but it seems unlikely that it’s devoted solely to the analysis of color.

- As is the case for most other visual attributes, our experience of color probably depends on the activity of neurons in several cortical areas.

Causes and consequences of representational drift

- The nervous system learns new associations while maintaining memories over long periods, balancing between flexibility and stability.

- Recent experiments reveal that neuronal representations of learned sensorimotor tasks continually change over time, even after animals achieved expert-levels of performance.

- How is behavior consistent despite ongoing changes in neuronal activity?

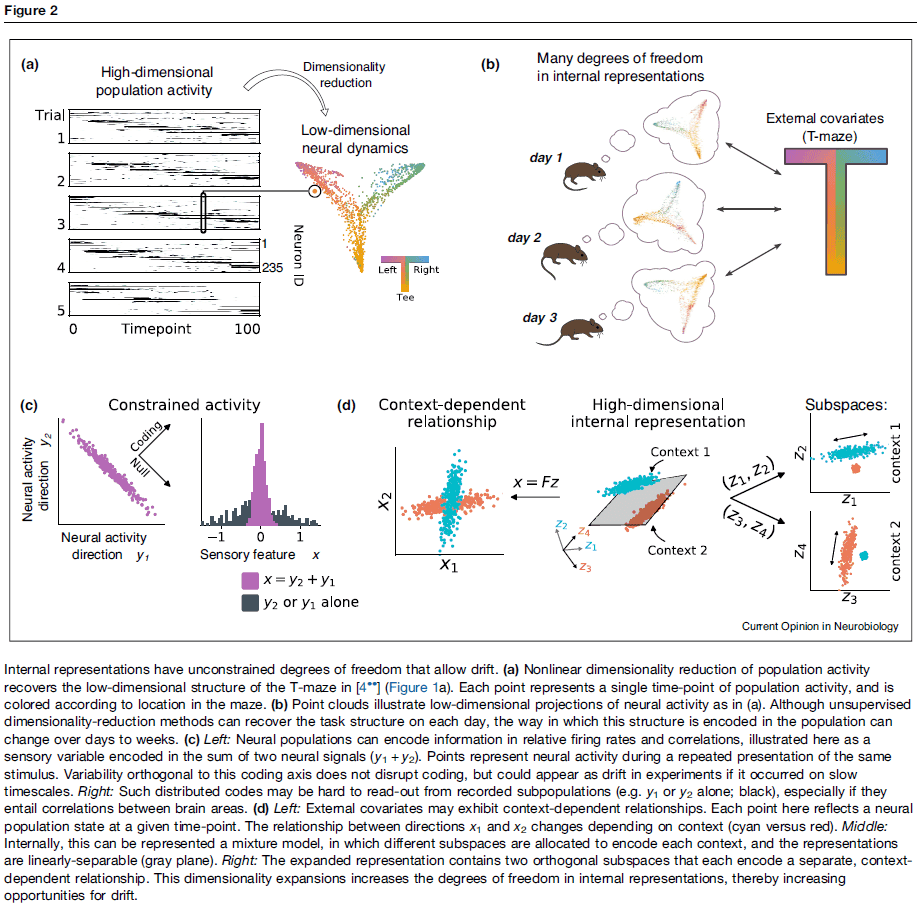

- This paper highlights recent experimental evidence for representational drift in sensorimotor systems and discusses how this fits into the framework of distributed population codes.

- We also argue that the recurrent and distributed nature of sensorimotor representations permits drift while limiting disruptive effects.

- The apparent instability of neuronal responses for fully learned tasks challenges the view that synaptic connectivity and individual neuronal responses correlate directly with memory.

- Recent experiments have found that neuronal representations of familiar environments and learned tasks reconfigure or “drift” over time.

- Representation: neural activity that’s correlated with task-related stimuli, actions, and cognitive variables.

- E.g. Single-cell receptive fields or population activity vectors that guide behavior.

- Representational drift: ongoing changes in these representations that occur without obvious changes in behavior.

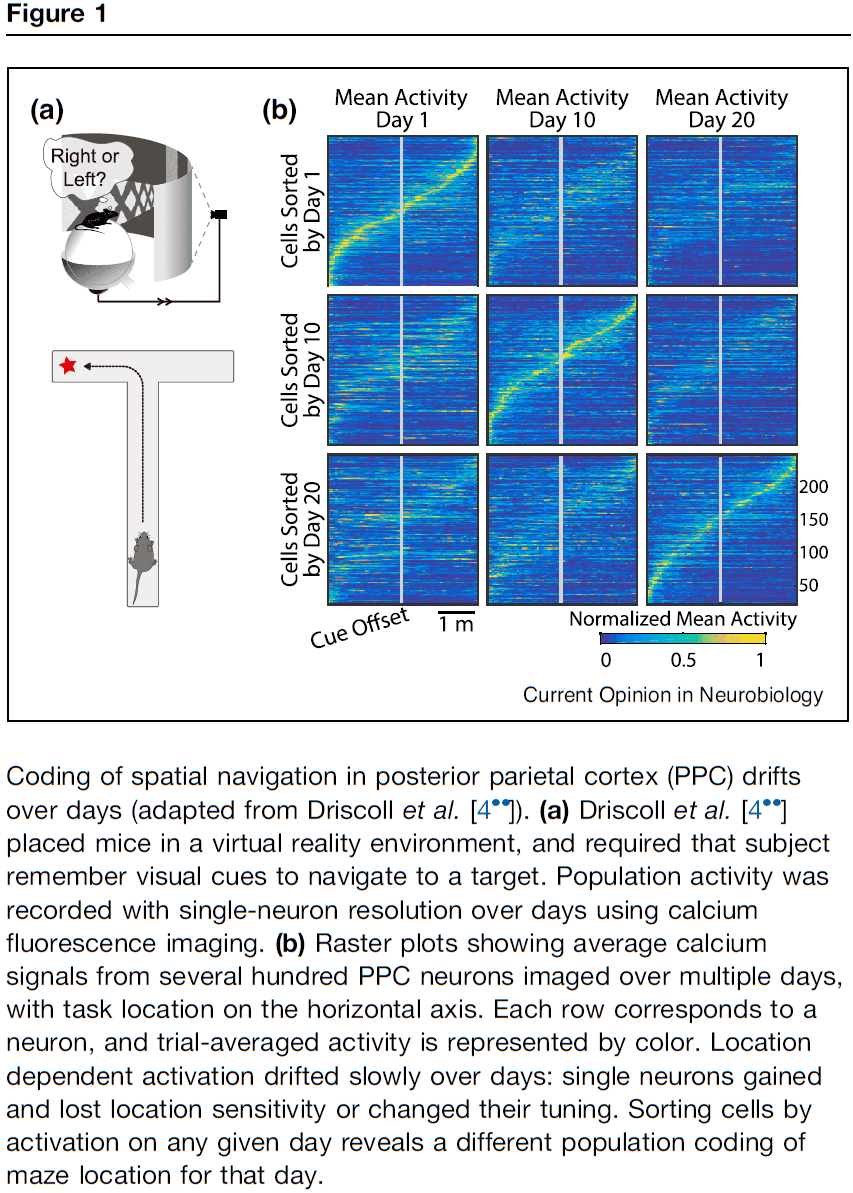

- E.g. In mice who learned to navigate a T-maze, neurons tend to be transiently active during task trials, with different neurons active at different parts of the trial. The posterior parietal cortex (PPC) representation wasn’t stable over multiple days and weeks.

- Similar types of drift have been reported in a number of brain areas.

- E.g. Hippocampus, sensory neocortex, motor neocortex.

- In the hippocampus, all dendritic spines are expected to turn over in several weeks, suggesting that circuits are continually rewired even though animals can maintain stable task performance and memories.

- We emphasize that drift isn’t seen in all brain areas and for all tasks.

- Nevertheless, the finding of representational drift raises questions about how behavior is learned and controlled in neural circuits, and what constitutes a memory of such behavior.

- Redundant representations may allow for some level of drift without disrupting behavior.

- E.g. Even in simple nervous systems, the existence of circuit configurations with different anatomical connectivity but similar overall function is well documented.

- The brain may therefore achieve robustness by preserving high-dimensional behavior while allow for a vast number of equivalent circuit configurations to be realized.

- E.g. A low dimensional task can be represented in higher dimensional population activity in a variety of configurations.

- An idea that emerges from the high-dimensional encoding of low-dimensional tasks is that of a null space.

- Null space: a subspace of population activity that’s orthogonal to a low-dimensional task representation.

- The null-space concept has been used to explain how a single neuronal population can represent multiple behavioral contexts.

- Because of the high-dimensional space for internal representations, neuronal activity could drift in directions unrelated to encoding or task performance.

- If the dimensionality of population activity is much higher than the dimensionality of the task, even random drift will lie mostly within the null space.

- Thus, high-dimensional population representations can tolerate drift and allow multiple circuit configurations leading to similar outputs, and thus similar behavior.

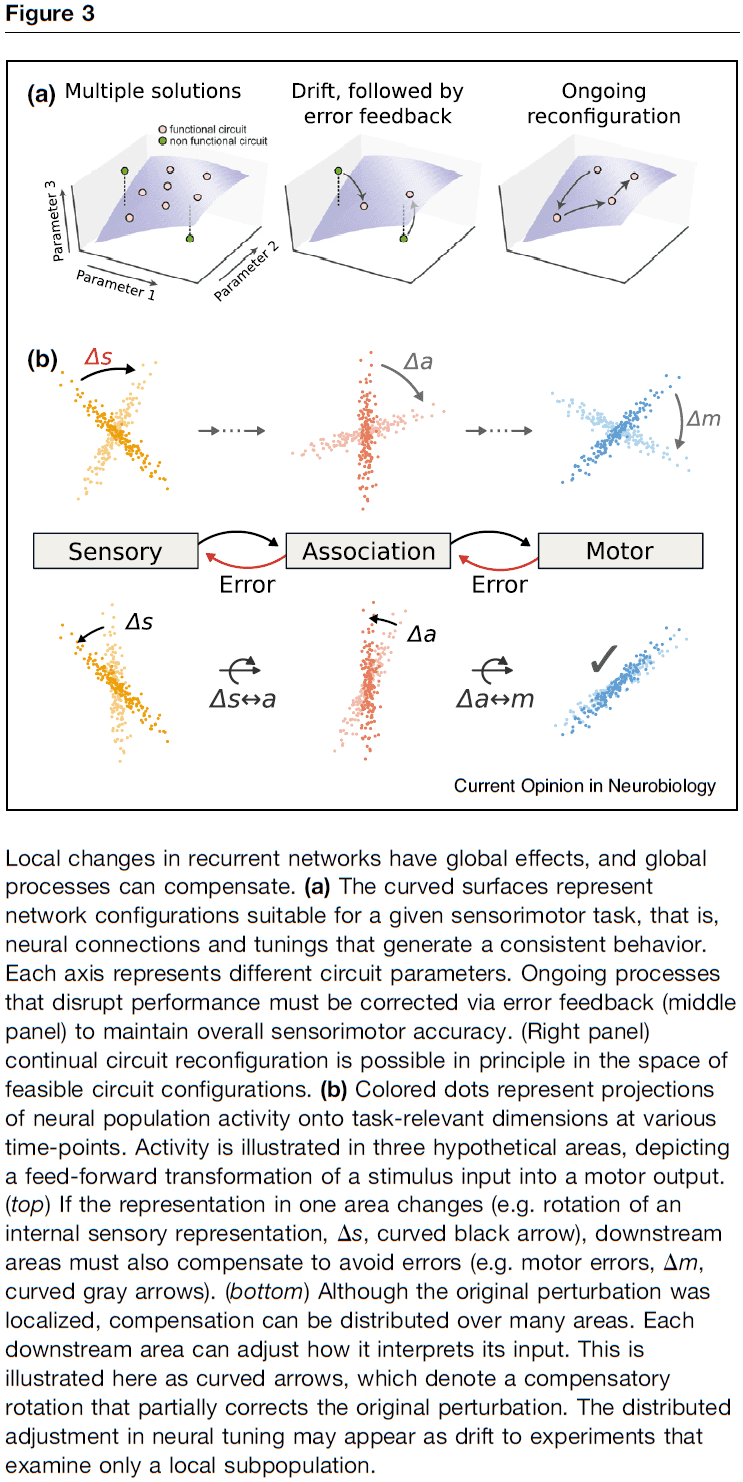

- Representational drift may be inevitable in distributed, adaptive circuits.

- Drift is sometimes considered as a passive, noise-driven process, but it could also reflect other ongoing processes such as learning.

- E.g. To prevent new associations from disrupting previously learned associations, the brain may need to re-encode them.

- Experiments on training mice to learn new sensorimotor associations (after having learned earlier associations) found that the same neurons appeared to be used for the representations of previously learned associations.

- Thus, representational drift could reflect learning and suggests that a neuronal population can be simultaneously be used for learning and memory.

- This idea of drift as ongoing learning is consistent with recent theoretical work.

- Even in the absence of explicit learning, representations may drift to encode information more efficiently.

- Drift may therefore be an expected consequence of ongoing refinement and consolidation.

- Regardless of the sources of drift, neuronal representations must remain within the subspace of equivalent representations or else behavior is impacted.

- Continual corrective action is needed to constrain neuronal representations on long timescales, and external stimuli could provide this corrective feedback.

- Another source of feedback could be internal error signals exchanged between recurrently connected brain regions.

- E.g. Spatial navigation requires consistent representations throughout sensory, association, and motor regions.

- Drift could serve important computational functions.

- E.g. Dropout to prevent overfitting. Time-stamping as the set of active cells conveys information not only about the environment, but also about time.

- Drift may allow the brain to sample from a large space of possible solutions, working towards optimal solutions while sampling enough possibilities to avoid globally suboptimal local solutions.

- The brain is an adaptive system and its structure changes.

- Integrating theories of collective neural dynamics, learning, and predictive coding in distributed representations are essential to understanding how sensorimotor representations evolve.

- Globally coordinated plasticity may be needed to preserve existing associations or in other words: “to stay the same, everything must change.” A form of neural homeostasis.

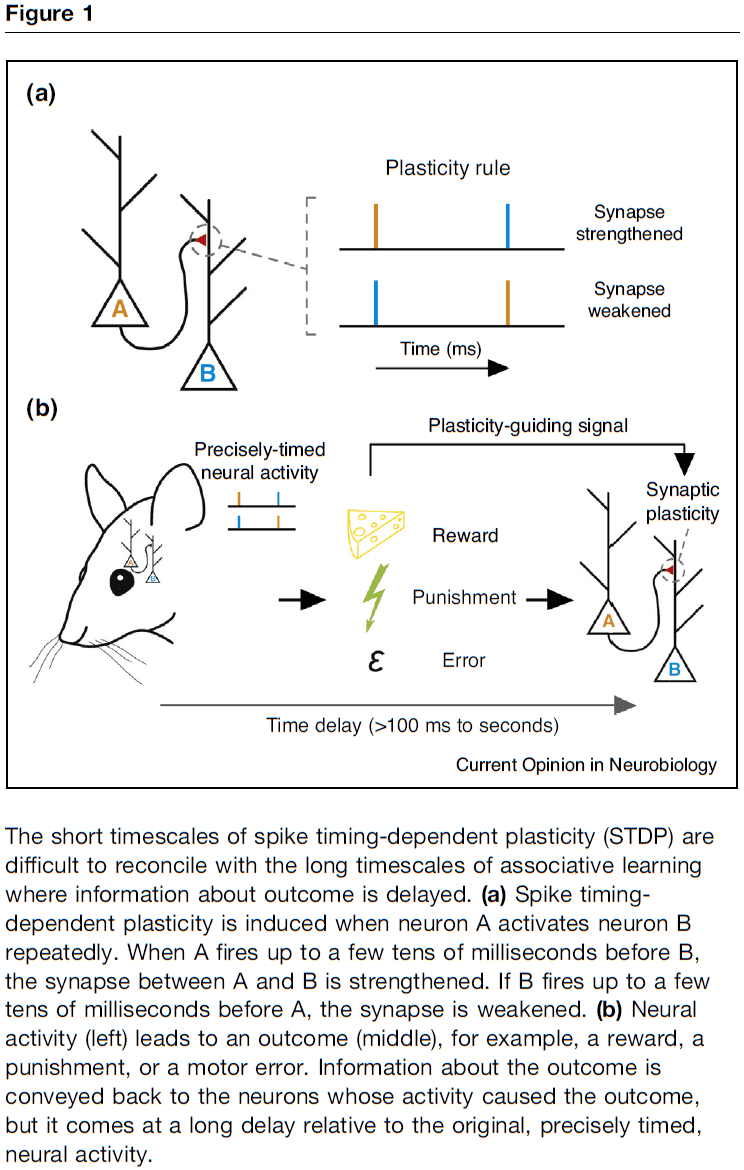

Beyond STDP — towards diverse and functionally relevant plasticity rules

- It’s important to understand the rules governing synaptic plasticity because it supports behavioral learning and is critical for memory.

- Recent discoveries suggest that rather than having universal rules for plasticity, there may be a diversity of rules, and that this diversity may be determined by the function of the neural circuit that each synapse is a part of.

- The search for plasticity rules has been based on Hebb’s postulate that “neurons that fire together wire together”.

- Hebbian plasticity addressed the question of causality in plasticity, but the discovery of spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) provided a framework for order dependence as well as causality.

- However, the necessity for postsynaptic action potentials (APs) in synaptic plasticity remains controversial as plasticity may be mediated by other depolarizing events in the postsynaptic cell.

- STDP-like plasticity: plasticity rules that require order-dependent and close temporal correlation of neural signals.

- One key problem with using STDP-like plasticity for all forms of associative learning is the difference in timescale between plasticity rules (tens of milliseconds) and behavioral time scale plasticity (minutes).

- How do we bridge the shorter synaptic timescales with the longer behavioral timescales?

- Temporal credit assignment: how to assign credit/blame in a neural circuit or synapse after delayed feedback.

- Associative learning is often guided by the outcome of the action such as reward signals.

- In such cases, learning may be supervised by a neuromodulatory signal rather than by synaptic activity.

- This questions the relevance of precise spike timing for neural circuits where learning is supervised by delayed and temporally diffuse neuromodulatory signals.

- Neuromodulators can also change the temporal requirements of precise spike timing necessary for inducing synaptic plasticity.

- The ability of modulatory inputs to affect plasticity has been shown in several different contexts and it can play a gating role or change the shape of the plasticity rule itself.

- Recent studies suggest that the timing rules for synaptic plasticity can be aligned with the behavioral and functional requirements of a circuit, contradicting the concept that plasticity rules are only based on close temporal correlations.

- Timing is only part of the picture as several other parameters influence plasticity.

- E.g. Neuronal firing rate, number of repetitions, and the cooperativity of synapses.

- Moreover, synaptic plasticity is far from being the only form of plasticity in a neural circuit.

- To summarize, coincidence-based rules for synaptic plasticity are no longer sufficient to explain the diversity of ways neural circuits can adapt and learn.

Anauralia: The Silent Mind and Its Association With Aphantasia

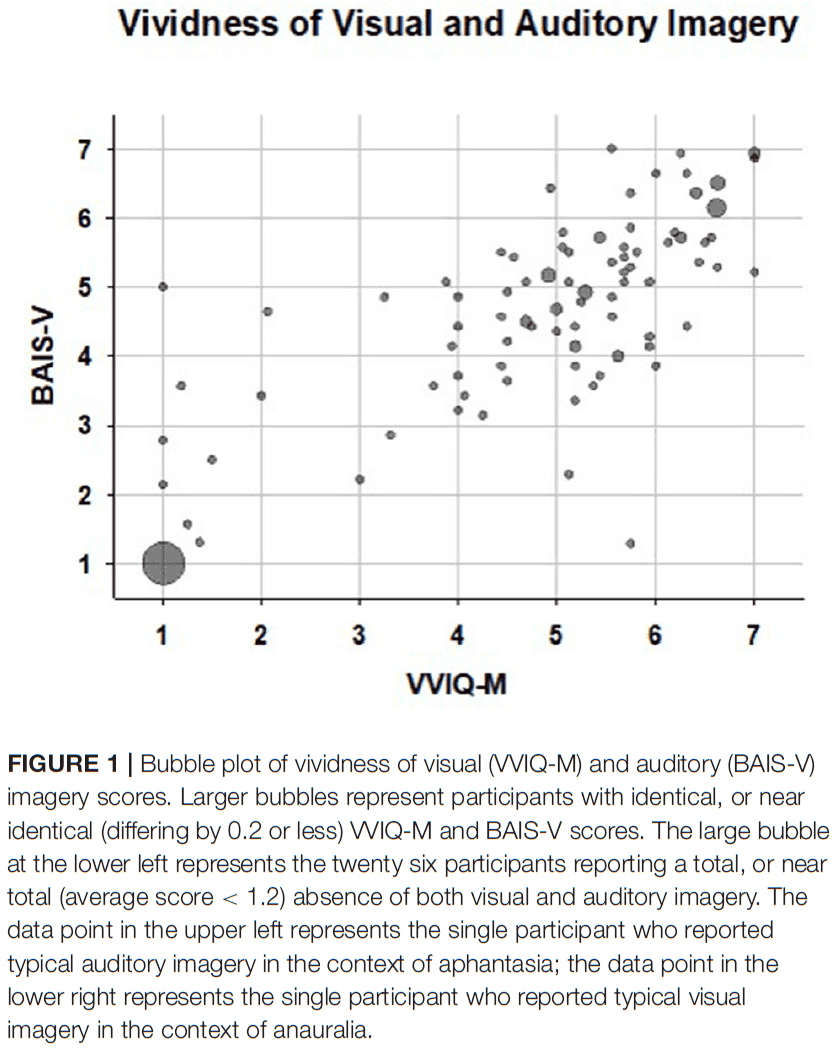

- Auditory imagery and visual imagery were found to be strongly associated in a sample of 128 participants.

- Most self-reported aphantasics report weak or absent auditory imagery, and people lacking auditory imagery tend to be aphantasic.

- Similarly, vivid visual imagery tends to co-occur with vivid auditory imagery.

- Because there’s no English word for the absence of auditory imagery, we propose a new term, anauralia, to refer to this phenomenon.

- Aphantasia: lack of visual imagery.

- Some individuals that have aphantasia also report weak or absent imagery in other sensory modalities.

- E.g. No “inner voice” or auditory imagery.

- Previous reports show that some aphantasics report an inner mental life that’s not only blind but also completely silent.

- E.g. “I silently think and silently read”, “I don’t have the experience people describe of hearing a tune or a voice in their heads.”

- Anauralia: lack of auditory imagery.

- This paper aims to evaluate possible associations and dissociations between visual and auditory imagery, and their absence.

- To assess auditory and visual imagery, we used the Bucknell Auditory Imagery Scale-Vividness (BAIS-V), the Bucknell Auditory Imagery Scale-Control (BAIS-C), and the Vividness of Visual Imagery Questionnaire (VVIQ-M).

- Out of the 128 participants, 34 were aphantasic and 20 were categorized as anauralic.

- Between these two groups, there was a large overlap with 82% of the aphantasic group experiencing very weak auditory imagery, and 97% of the anauralic group experiencing very weak visual imagery.

- The association between aphantasia and anauralia was highly reliable with a chi-square of 93.42 and p < 0.001.

- The other extreme, hyperphantasia and hyperauralia, was also found to be reliably associated with each other in that strong auditory imagery correlated with strong visual imagery and vice versa.

- 1/34 aphantasic individuals reported average auditory imagery, and 1/29 anauralic individuals reported average visual imagery.

- So, it appears that auditory imagery can be dissociated, to some extent, from visual imagery, and the reverse.

- However, strong dissociations weren’t observed as no aphantasic participants were hyperauralic, and no anauralic participants were hyperphantasic.

- We found that visual and auditory imagery were strongly associated as a large majority of self-reported aphantasics were also anauralic, and vice versa.

- Aphantasia has been linked with poor autobiographical memory and face recognition problems.

- But with the existence of anauralia, this confounds previous findings and it’s unclear what causes poor autobiographical memory and poor face recognition in these individuals.

- The lack of auditory imagery may play a significant role in at least some of the associations observed in the aphantasia literature.

- While the presence of a strong association between aphantasia and anauralia suggests that common mechanisms are involved when generating visual and auditory images, the existence of dissociations indicates that use of common mechanisms and pathways isn’t mandatory.

- The literature on sensory imagery has been dominated by work on visual sensory imagery, with auditory imagery arguably receiving less attention than it deserves.

Synaptic vesicle pools are a major hidden resting metabolic burden of nerve terminals

- The human brain has a small safety margin with respect to fuel supply as a two-fold drop in blood glucose level results in severe neurological consequences.

- Nerve terminals are the likely source of this metabolic vulnerability as they’re remarkably sensitive to brief fuel supply interruption.

- E.g. Complete halting of synaptic vesicle recycling within minutes of fuel deprivation.

- This vulnerability may reflect the limits of the local ATP synthetic machinery’s ability to balance both increased ATP demand and fundamental basal metabolic costs that are always incurred.

- As an organ, the brain is energetically expensive in that it consumes 20% of the body’s fuel but only represents 2-2.5% of its mass.

- Although a large fraction of this energy consumption is driven by electrical activity, the brain likely has high resting metabolic rates because severe reduction of the brain’s electrical activity only decreases fuel consumption by two- to three-fold.

- This paper shows that nerve terminals have a high resting metabolic energy demand that’s independent of electrical activity, and that synaptic vesicle (SV) pools are major energy consumers.

- Findings of this paper

- The high resting metabolic rate is due to SV-resident vacuolar-type ATPase (V-ATPases) compensating for a previously unknown constant proton (H+) efflux.

- This steady-state proton efflux is mediated by the vesicular neurotransmitter transporter independent of the SV cycle.

- This efflux accounts for about half of the resting synaptic energy consumption.

- Suppression of this transporter significantly improves the ability of nerve terminals to withstand fuel withdrawal.

- The vesicular proton pump, and not the plasma membrane, accounts for a large resting basal ATP consumption in nerve terminals.

- The action of sodium-ion/potassium-ion-ATPase (NaK-ATPase) to restore ionic gradients is considered to be one of the largest metabolic costs in the active brain.

- In the absence of action potential firing, the NaK-ATPase compensates for any leaking currents across the plasma membrane.

- Unexpectedly, inhibiting NaK-ATPase using ouabain had no measurable impact on the kinetics of ATP depletion.

- This suggests that relatively few sodium and potassium ions need to be pumped across the plasma membrane to maintain the resting membrane potential.

- Therefore, we consider alternative mechanisms at presynaptic terminals to explain basal metabolic dynamics.

- Although we expect ATP expenditure for filling vesicles with neurotransmitter, it’s less clear in a resting vesicle pool whether there is any residual activity that might account for part of the resting metabolic load, a state when one expects most SVs to be full of neurotransmitter.

- To test this, we blocked V-ATPase using bafilomycin which lead to significantly reduced basal ATP consumption.

- These data unmask V-ATPase as a main energy burden in resting synapses that accounts for slightly less than half of the resting ATP consumption.

- Given the large total number of nerve terminals in the brain and that this burden is constantly present, the resting SV pools in total likely make up a substantial energy burden in the brain.

- Further experimentation found that there’s a steady-state efflux of protons from SVs, which is compensated for by V-ATPase.

- Our data shows that a constant proton flux accounts for about 44% of resting synaptic ATP consumption and that this flux is mediated by vGlut1.

- Overall, the results reveal that the SV pool is a major source of metabolic activity even in the absence of electrical activity and neurotransmission.

- In control neurons, the removal of glucose from the environment led to the gradual slowing of SV recycling.

- The findings from this paper provide a compelling explanation for why nerve terminals are so sensitive to metabolic compromise and why brain tissue has a resting metabolic rate that’s much higher than other tissues.

- The presence of SVs themselves and their intrinsic reliance on V-ATPase to power neurotransmitter filling have made them sensitive to routes of efflux for protons from the vesicle lumen, which sustains V-ATPase activity, creating a constant energetic burden.

- We don’t know the precise route of proton efflux in glutamatergic vesicles, but we do know that vGlut is a critical mediator.

- One limitation of these findings is that only glutamatergic vesicles were studied, so we aren’t sure if these findings generalize to dopaminergic or GABAergic SVs.

- Given the vast number of synapses in the human brain and the presence of hundred of SVs at each of these synapses, this hidden metabolic cost of quickly returning synapses to a “ready” state comes at the cost of major ATP and fuel expenditure, contributing significantly to the brain’s metabolic demands.

The Defensive Activation Theory: REM Sleep as a Mechanism to Prevent Takeover of the Visual Cortex

- Brain regions maintain their territory with continuous activity.

- E.g. If activity slows or stops due to loss of input, the territory will be taken over by its neighbors.

- Surprisingly, the speed of takeover is fast and is measurable within an hour.

- This leads us to a new hypothesis on the origin of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep called the defensive activation theory.

- Defensive activation theory: that REM sleep serves to amplify the visual system’s activity periodically throughout the night, allowing it to defend its territory against takeover from other senses.

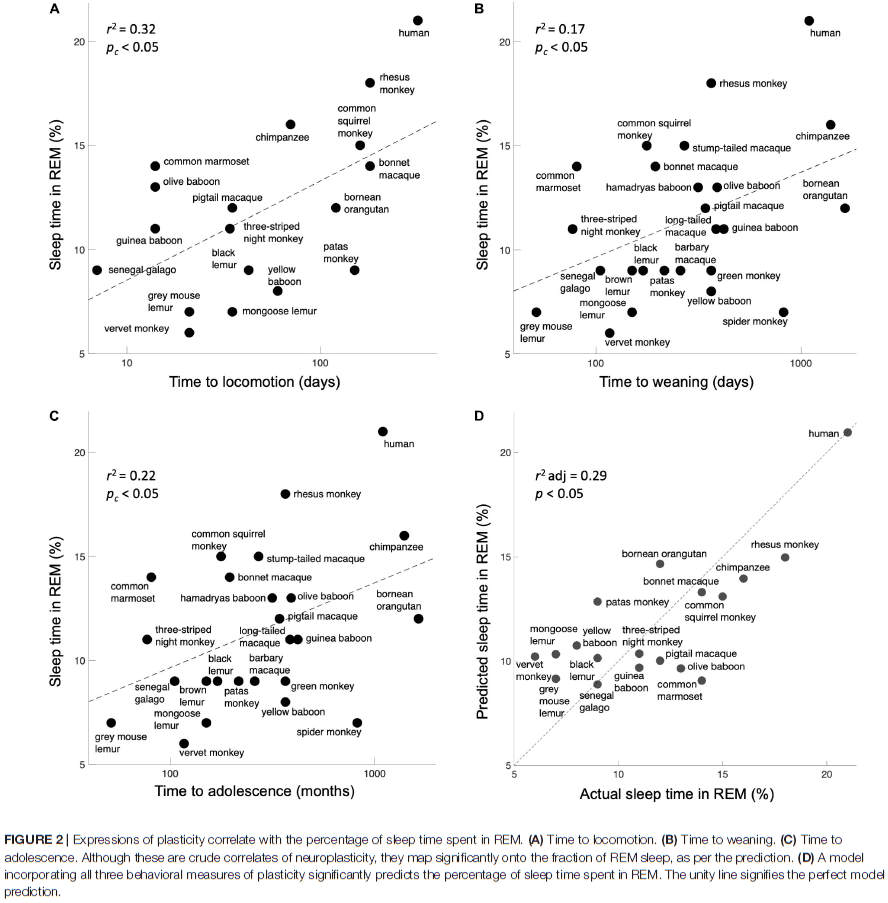

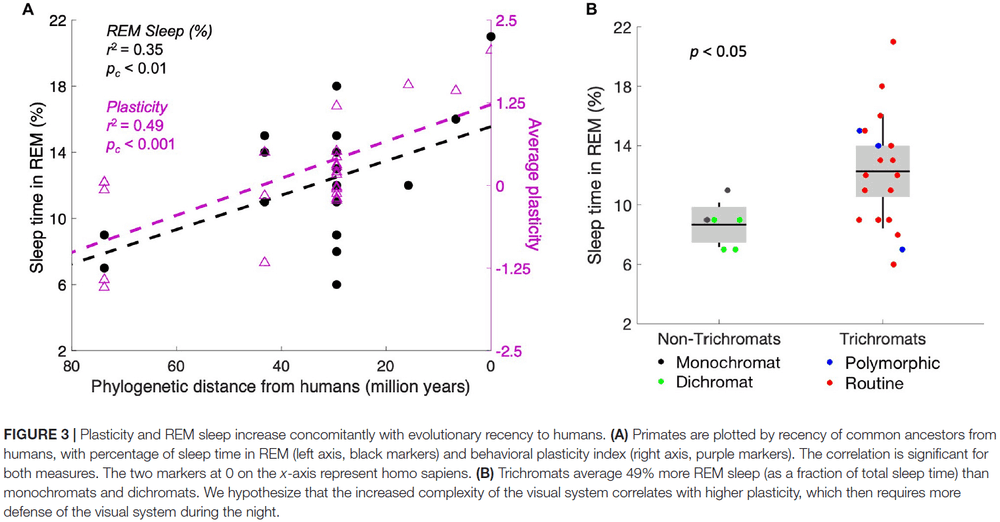

- In support of this hypothesis, we found that measures of plasticity across 25 primate species correlate positively with the proportion of REM sleep.

- We further found that plasticity and REM sleep increases with newer evolved species up to humans.

- Finally, our hypothesis is consistent with the decrease in REM sleep and parallel decrease in neuroplasticity that comes with aging.

- Why do we dream? Does dreaming have a purpose or is it meaningless noise? And why are dreams so richly visual?

- Potential reasons behind REM sleep

- Energy and temperature control

- Psychological health

- Learning

- Sensorimotor integration

- This paper leverages recent findings on neural plasticity to propose a novel hypothesis that can account for the amount of REM sleep across species.

- Just as sharp teeth and fur are useful for survival, so is neural plasticity.

- Neural plasticity: the brain’s ability to adjust its parameters, enabling learning, memory, and behavioral flexibility.

- At the scale of brain regions, neuroplasticity allows areas associated with different functions to gain or lose neural territory when inputs to that function slow, stop, or shift.

- E.g. In congenitally blind individuals, the occipital cortex is taken over by other senses such as audition and somatosensation.

- We find that the brain undergoes rapid changes when input stops.

- Rapid neural reorganization happens not only in the newly blind, but also in sighted people with temporary blindness.

- E.g. Temporarily blindfolded people that learned Braille showed activation in the occipital, somatosensory, and auditory cortex while reading Braille. And when the new occipital lobe activity was disrupted using TMS, the Braille-reading advantage of the blindfolded subjects went away. After the blindfold was removed, the response of the occipital cortex to touch and sound disappeared within a day.

- Of interest here is the unprecedented speed of the change.

- The rapidity of change may be explained not by the growth of new connections, but by the unmasking of pre-existing non-visual connections in the occipital cortex.

- This rapid redistribution of neural territory leads us to a new hypothesis for the brain’s activity at night. As at night, the visual system in particular has a unique problem: it’s cast into darkness for an average of 12 hours every day.

- Given that sensory deprivation triggers takeover by neighboring territories, how does the visual system compensate for this cyclic loss of input?

- Defensive activation theory: the brain combats neuroplastic incursions into the visual system by keeping the occipital cortex active at night.

- Thus, REM sleep exists to keep the visual cortex from being taken over by neighboring cortical areas at night.

- After all, night doesn’t diminish touch, hearing, or smell, but only vision is occluded by darkness.

- Review of REM sleep

- Rapid eye movement during sleep is thought to be associated with the visual experience of dreaming.

- REM sleep is triggered by a specialized set of neurons in the pons, which has two consequences.

- First, it keeps the body immobile during REM sleep by paralyzing major muscle groups, thus allowing the brain to simulate visual experience without moving the body simultaneously.

- Second, we experience vision when waves of activity travel from the pons to the lateral geniculate nucleus and then to the occipital cortex. These waves are called ponto-geniculo-occipital (PGO) waves.

- This visual cortical activity is presumably why dreams are pictorial and filmic instead of conceptual or abstract.

- These nighttime volleys of activity are anatomically precise as the PGO waves only happen for the occipital cortex and no other sensory modality.

- The defensive activation theory predicts that the higher an organism’s neural plasticity, the higher its ratio of REM to non-REM sleep. And this relationship should apply across species and within an organism’s lifespan.

- We tested our hypothesis by comparing 25 species of primates on behavioral measures of plasticity and the fraction of sleep time spent in REM sleep.

- Since we don’t have direct measures of visual cortical plasticity, we assume that the plasticity of different brain regions generally correlates within a species.

- Does the general plasticity of a species correlate with the percentage of REM sleep time?

- We found significant correlations for time to locomotion, time to weaning, and time to adolescence with sleep time in REM.

- For control, we used four other variables for each species: body mass, body length, number of offspring, and average lifespan and found non-significant correlations with REM sleep.

- The findings show that more REM sleep correlates with more plasticity.

- Next, we analyzed measures of plasticity and REM sleep as a function of phylogenetic distance from humans.

- The data show that both plasticity and REM sleep correlate significantly with phylogenetic distance from humans.

- This finding suggests that plasticity increases as brain complexity increases.

- The data are consistent with the prediction that there’s a significant decrease in REM sleep across the lifespan.

- REM sleep becomes less necessary as neural circuitry becomes less flexible.

- This decline in plasticity is consistent with the aging brain’s declining ability to recover from damage.

- The defensive activation theory may be part of a more general principle that more plastic systems require more active maintenance.

- E.g. REM sleep when deprivation is regular and predictable, tinnitus or phantom limb syndrome when deprivation is regular and unpredictable, and hallucinations when deprivation is irregular and unpredictable.

- The hypothesis could be tested more thoroughly with direct measures of cortical plasticity.

- If dreams are visual hallucinations that prevent neuroplastic takeover of the visual cortex, we expect to find similar visual hallucinations in awake people with prolonged periods of sensory deprivation.

- And indeed, visual hallucinations have been reported by individuals deprived of visual input, which may represent the same mechanism of cortical maintenance.

- E.g. Just as a thermostat runs based not on the time of day but on the temperature of the building, PGO waves may be triggered not by circadian rhythms but rather by feedback from visual cortex that it’s experiencing a decline in externally driven activity.

Are Bigger Brains Better?

- Studies relating brain size to behavior and cognition have rarely included information from insects, of whom show complex motor repertoires and extensive social structures.

- What are large brains for?

- Part of the answer is that large brains are due to large neurons that are necessary in large animals due to basic biophysical constraints.

- Larger brains also have more neuronal circuits, which add precision to perception and action, enable more parallel processing, and enlarge storage capacity.

- Modularity and interconnectivity also become more important in large brains.

- For comparison, a whale’s brain can weigh up to 9 kg, human brains can weigh between 1.25-1.45 kg, and a honeybee’s brain has a volume of ~1mm3 and has less than a million neurons.

- One of the biggest problems in correlating brain size with behavioral ability is when we consider insects, especially social ones.

- Learning speed can’t be used to measure intelligence because the honeybee’s speed at color learning is superior to all vertebrates that have been studied.

- How do insects generate such diverse and flexible behavior with so few neurons? And if so much can be achieved with relatively little neuronal hardware, what advantages are obtained with a bigger brain?

- Many increases in certain brain areas only result in quantitative improvements.

- E.g. More detail, finer resolution, higher sensitivity, greater precision.

- If the increased resolution is to be used behaviorally, then it needs to be processed by neural machinery downstream of sensory receptors.

- Insects and vertebrates have converged on similar solutions to process information, namely retinotopic neural maps consisting of local neuronal circuits arranged in repeated columns, the number of columns depending on the number of inputs from the retina.

- E.g. The primary visual cortex in mammals increases dramatically with eye resolution as in mice, the area is 4.5 mm2, in macaques 1200 mm2, and in humans 3000 mm2.

- This assumes that the diversity of ways in which information is processed doesn’t change.

- Larger eyes not only have increased spatial detail, but also are also faster in processing speed.

- E.g. Some large insect photoreceptors can respond to light frequencies far beyond the typical range of mammalian photoreceptors.

- This requires that the entire neural pathway be changed to support and process this higher frequency information.

- E.g. Increased axon diameters, synapses capable of higher rates of vesicle release, increased neural substrate for storing more detailed stimuli.

- Thus, a reverberation of size differences from the sensory periphery through to several subsequent stages of information processing occurs with new sensors.

- The principle of repetitive, modular organization occurs in several areas of the brain, not just those engaged in vision.

- E.g. Peripheral processing of olfactory information is similar in both vertebrates and insects.

- The common fruit fly has 43 olfactory glomeruli, honeybees have 160, humans have 350, and mice have 1000 glomeruli.

- Thus, although insects have fewer glomeruli and, presumably, a reduced odour space in comparison to many vertebrates, the differences in peripheral circuitry are quantitative rather than differing fundamentally in the type of neural computation performed.

- The principle of scaling sensory function with body size is likely repeated in other sensory modalities.

- E.g. Somatosensory mapping in larger animals will require corresponding larger brain areas.

- In conclusion, larger animals possess larger sense organs, which facilitate more detailed mapping of the world around them, assuming that these sense organs are accompanied by central neural circuits that process the peripheral information.

- There’s no reason to assume that improvements in the quantity of sensory processing necessarily results in higher intelligence.

- Instead, higher intelligence (the quality of a sensory system) depends on sensory structure/architecture and the absolute number of neurons.

- So, although comparative studies almost invariably use relative brain volume, it’s primarily the absolute, and not relative number of neurons, their size, connectivity, and available energy, that affect information processing within the nervous system.

- “A system […] is more complex if it can do more kinds of things.” - Changizi

- The million-fold increase in a large mammal’s brain relative to an insect’s does allow mammals to do more “kinds of things”.

- Similar to what we’ve seen in sensory systems, motor systems in bigger brains add relatively little in terms of the diversity of neuronal operations.

- E.g. Increased precision in motor skills is correlated with increases in the corresponding motor cortex area’s size.

- There’s sparse evidence that the insect motor system has a simpler architecture than that of large-brained mammals.

- E.g. Locusta migratoria has 296 muscles compared to the 316 muscles in primates.

- Insects often outperform vertebrates in terms of speed of movement but just as in vertebrates, motor actions can be reduced to a coordinated series of precisely timed muscle contractions.

- E.g. In both insects and vertebrates, there are descending pathways that control the activity of central pattern generators that can be modified based on sensory feedback. Both also have local reflex circuits.

- Relatively few interneurons may be necessary to produce novel behaviors using existing interneurons, motor neurons, and muscles.

- Thus, novel behaviors could arise by small numbers of neurons using the basic architecture of existing behaviors, but recruiting them in different ways.

- The motor systems of insects aren’t necessarily inferior to those of mammals in ways that differences in brain size might suggest.

- E.g. While insect muscles are innervated by fewer motor neurons than vertebrates, this may not affect precision as vertebrates have more muscle fibers.

- The differences in behavioral repertoire size between insects and large-brained vertebrates are much less pronounced than one might expect from differences in brain size.

- The acquisition of novel pathways can produce novel behaviors.

- Absolute brain volume of both vertebrates and insects increases with body mass, although relative brain volume decreases.

- As brain regions increase in size, the distance information travels also increases.

- This distance can introduce substantial delays between regions.

- In the mammalian cortex, the volume of connections between distant brain regions (white matter) increases disproportionately faster than that of local processing (grey matter).

- Brain regions segregate to maintain a high level of local connections while reducing the number of long distance connections.

- Novel brain regions and the circuits within are free to diversify, producing novel behaviors.

- Insects lack myelin, which is present in mammals and arthropods, so increased conduction velocity is achieved solely through increased axon diameters.

- The largest axon diameters are found in interneurons with long range connections that form part of the escape circuit.

- Although these interneurons increase the volume of the ventral nerve cord, there are typically very few of such neurons.

- The small distances within insect nervous systems allow the majority of information to be transferred in interneurons with small axon diameters using analogue signals.

- However, the transmission of analogue signals is restricted due to their inability to propagate far and their accumulation of noise over long distances.

- E.g. Analogue signals are only used in the vertebrate nervous system in short sensory receptors and some visual interneurons.

- Neural circuitry can’t be infinitely miniaturised due to noise from ion channels at that scale.

- The computational power of a brain isn’t dependent on relative brain size, but on absolute brain size, the number and size of neurons, the number of connections among them, and the metabolic rate of the tissue.

- The upper rate of APs that can be sustained is determined by the specific metabolic rate, which is higher in smaller brains.

- Thus, smaller brains can maintain a higher density of computations.

- Serial and parallel processing are essential for computing novel receptive fields and generating computational maps.

- E.g. Processing the computation of variables not directly represented in sensory input such as sound location.

- In larger brains, more parallel processing pathways and stages of serial processing can be added more easily than in insect brains where space imposes more severe constraints.

- In insects, neurons representing variables computed by combining multiple sources of sensory information appear to be present, but in smaller numbers than in vertebrates.

- As there’s no adult neurogenesis in bees, learning occurs by enhanced dendritic outgrowth and branching of Kenyon cells in each mushroom body.

- Because larger brains can extract and store more information, having larger memory stores facilitates the generation of novel solutions based on previously stored information.

- The search for correlations between brain sizes and cognition is riddled with complications.

- The majority of differences in brain volume, especially between species of different sizes, is related to the animal’s need to support larger sense organs and their need to move larger bodies.

- Bigger sense organs requires larger amounts of neural tissue to evaluate the information, providing more sensitivity and detail, but not necessarily higher intelligence.

- It’s now clearer that small brains can achieve many more types of cognitive operations than assumed.

- We argue that new neurons recruited into novel pathways and novel brain regions, resulting in greater serial and parallel processing of information, are more likely to contribute to qualitative changes in behavioral performance.

Computational Neuroscience

- The ultimate goal of computational neuroscience is to explain how electrical and chemical signals are used in the brain to represent and process information.

- At the time of this paper, neuroscientists have yet to understand how the nervous system enables us to see and hear, to learn and remember, and to plan and make choices.

- It’s difficult to study the relation between perception and the activity of single neurons because perception is the result of activity in many neurons in many different parts of the brain.

- Explaining higher functions is difficult because nervous systems have many levels of organization.

- E.g. Molecular, systems, local circuits, columns, topographic maps.

- Certain properties aren’t found in components of a lower level because they emerge from the organization and interaction of these components.

- E.g. Rhythmic pattern generation.

- Advantages of brain models

- Can make the consequences of a complex, nonlinear brain system with many interacting components more accessible.

- New phenomena may be discovered by comparing the predictions of simulation to experimental results.

- Experiments that are difficult or impossible to perform in living tissue can be simulated.

- Mechanical and causal explanations of the brain are different from computational explanations.

- The main difference being that a computational explanation refers to the information content of the physical signals and how they’re used to complete a task.

- E.g. A mechanical explanation of a slide rule is that certain marks are lined up and the result is read. A computational explanation is that the marks on the sliding rule correspond to logarithms, and adding two logarithms is the same as multiplying the pair of numbers.

- Thus, the physical system carries out a computation by virtue of its relation to a more abstract algorithm.

- Classes of brain models

- Realistic: a very large-scale simulation that tries to use as much cellular detail as possible.

- E.g. Hodgkin-Huxley model at the single-neuron level and Hartline-Ratliff model at the network level.

- The realism of the model is both a weakness and strength.

- As the model is made more realistic by adding more variables and parameters, the danger is that the simulation ends up as poorly understood as the nervous system itself.

- Simplifying: captures important principles and isolates the basic computational problems that govern the design of the nervous system.

- E.g. Connectionist models, parallel distributed processing, artificial neural networks.

- Abstract away the complexity of neurons and networks in exchange for analytical tractability.

- Are an important bridge to computer science and other fields that study information processing.

- Neuromorphic: hardware devices that directly mimic the circuits in the brain.

- Review of Carver Mead and his approach of using analog VLSI to model the retina.

- Realistic: a very large-scale simulation that tries to use as much cellular detail as possible.

- No notes for the section “Specific Examples of Brain Models”.

- Examining the outputs of a simple cell, it’s “projective” field by analogy with the input receptor field, was critical in uncovering its function in the network.

- Neither realistic nor simplifying brain models should be used without considering their strengths and weaknesses.

- E.g. Realistic models require immense data and it’s too easy to make a complex model fit a limited subset of data. Simplifying models are dangerously seductive and the model can become an end in itself and lose touch with nature.

- Ideally, both models should complement each other.

- At this stage in our understanding of the brain, it may be fruitful to focus on models that suggest new and promising lines of experimentation.

- A model should be considered a provisional framework for organizing possible ways of thinking about the nervous system.

Motor prediction

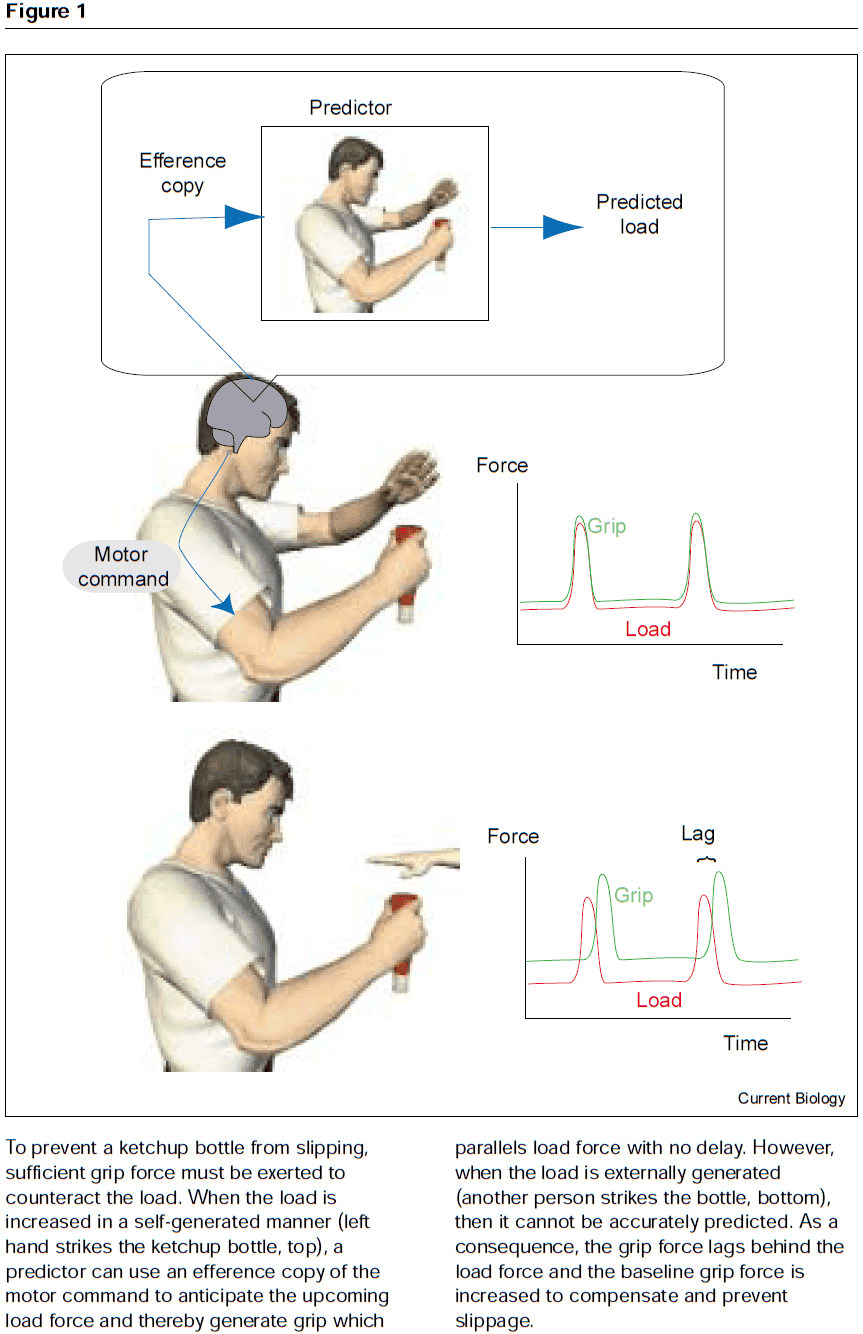

- Review of efference copy as a solution to how we localize visual objects.

- Prediction: estimating future states of a system.

- To predict the consequences of a motor command, the system must simulate the dynamic behavior of our body and environment using an internal forward model.

- This model captures the forward or causal relationship between actions and their consequences.

- Forward models aren’t fixed but must be learned and updated through experience and feedback.

- Uses of motor prediction in sensorimotor control

- State estimation

- Using sensory information to estimate state can lead to large errors, especially for fast movements, because of delays due to transduction, conduction, and processing.

- Another option is to estimate state using prediction based on motor commands.

- Here, the prediction is made before the movement and thus isn’t as delayed, but the prediction will drift over time if the forward model isn’t accurate.

- The solution is to combine both sensory feedback and motor prediction to estimate the current state.

- E.g. Use the forward model to predict state and use sensory feedback to update and correct the forward model.

- Depending on the action, the nervous system will rely more on one type of information than the other.

- E.g. For unpredictable objects such as flying a kite or holding the hand of a child, the system priorities sensory feedback. For predictable objects such as lifting an object, the system priorities forward model prediction.

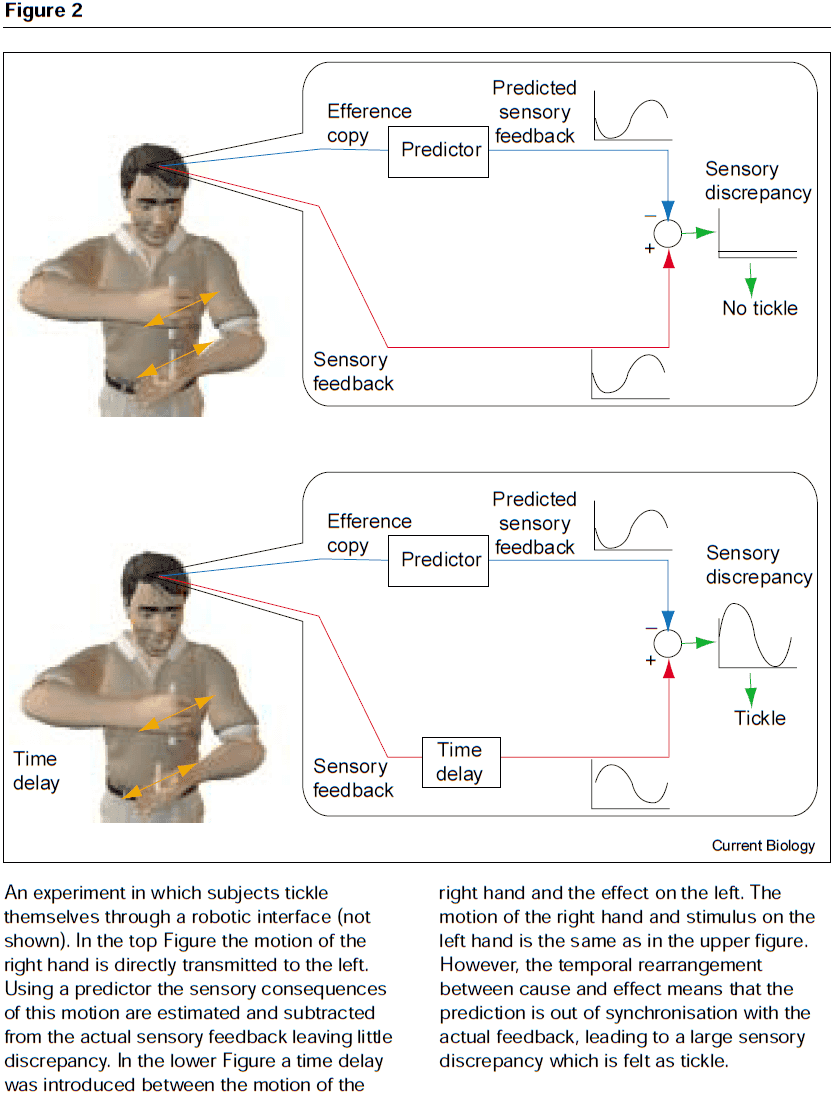

- Sensory confirmation and cancellation

- Prediction allows us to filter incoming sensory information by dampening unwanted signals and highlighting critical signals.

- E.g. Information from self-generated motion can be ignored, which enhances external-generated motion.

- E.g. Tickling ourselves is felt less intensely than when others tickle us. If the tickle is delayed, the greater the delay, the more ticklish the percept. This is presumably due to a reduction in the ability to cancel the sensory feedback based on the motor command.

- When the predicted sensory feedback matches the actual feedback, the motion is attributed to being generated by me. When it doesn’t match, the unpredicted feedback is attributed to others.

- Experiments have found that damage to the left parietal cortex can lead to the inability to determine whether movements are owned or not.

- The CNS is particularly sensitive to unexpected events or the absence of an expected event, both of which evoke reactive responses.

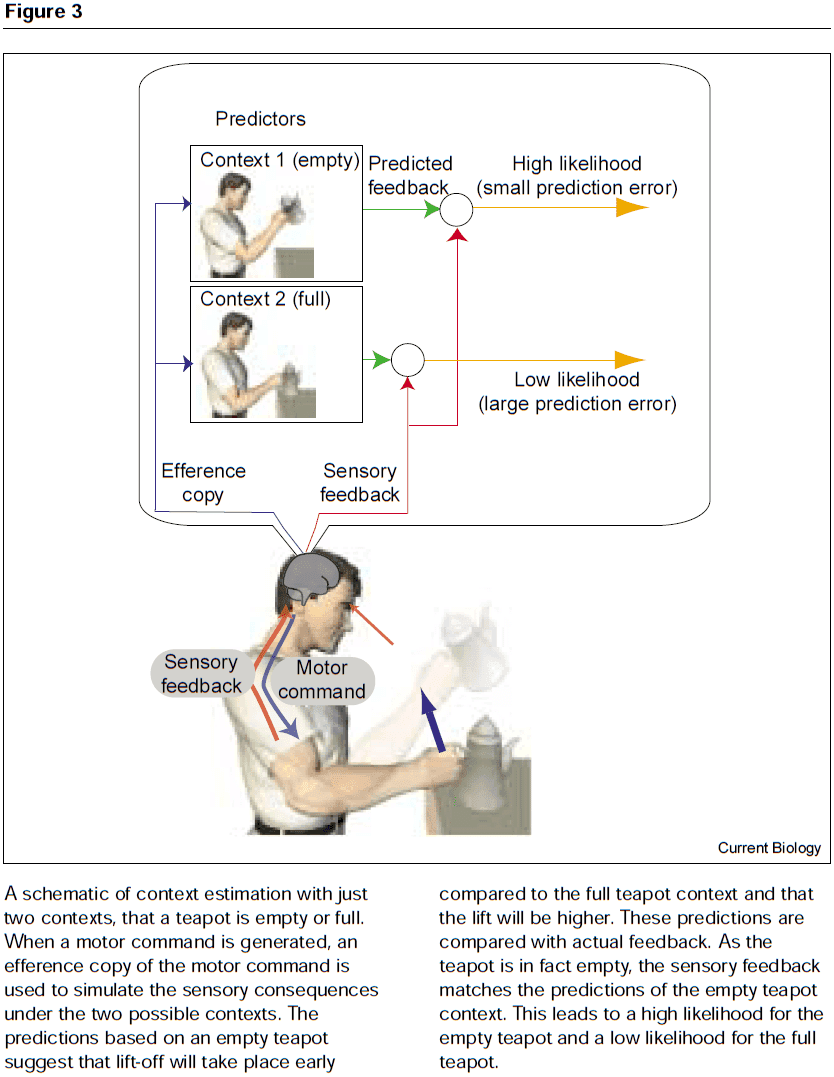

- Context estimation

- When faced with an unknown object, we identify the context and select the appropriate motor controller to handle such object.

- How does the brain select the appropriate controller?

- One solution, called the MOdular Selection and Identification for Control (MOSAIC) model, proposes that the when lifting an object, the brain simultaneously runs multiple forward models that predict the behavior of the motor systems when interacting with different, previously learned object.

- Each forward model predicts the expected sensory feedback and each model is paired with a controller, forming a predictor-controller pair.

- If the prediction of one of the forward models closely matches the actual sensory feedback, then its paired controller will be selected and used to determine subsequent motor commands.

- State estimation

- Prediction is essential for motor control, but may also be used in high-level cognitive functions.

- The idea of a forward model may provide a general framework for prediction in all cognitive domains.

- It may be that the same computational mechanisms which developed for sensorimotor prediction have adapted for other cognitive functions.

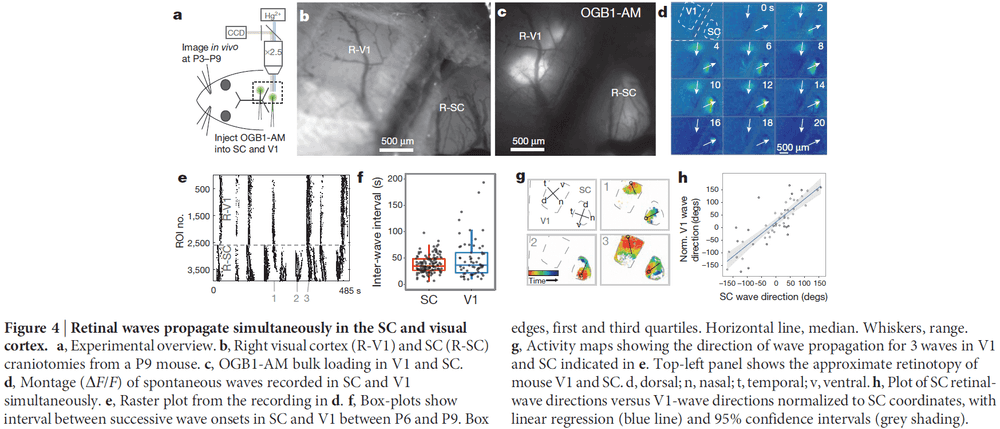

Retinal waves coordinate patterned activity throughout the developing visual system

- Spontaneous activity is an emergent property of the immature nervous system that’s thought to mediate synaptic competition and instruct self-organization in many developing neural circuits.

- If spontaneous activity is structured to the topographic organization of sensory and motor circuits, then this activity could provide a template for activity-dependent development of downstream synaptic pathways throughout the nervous system.

- Whether spontaneous patterned activity exists and is communicated through all levels of organization for any sensory system during development is unknown.

- In the developing visual system, isolated retinas have propagating bursts of action potentials (APs) among neighbouring retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) called retinal waves.

- Retinal waves propagate to higher-order visual structures in the central nervous system and are thought to play a key role in the activity-dependent refinement of topographic neural maps in the superior colliculus (SC), dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus (dLGN), and visual cortex.

- However, the role of retinal waves in neural-circuit development remains controversial because their existence has never been demonstrated in vivo.

- This paper aims to establish whether travelling waves of spontaneous retinal activity occur in neonatal mice in vivo, and to determine whether these waves convey spatiotemporal patterns used in the activity-dependent refinement of visual maps throughout the visual system before the onset of vision.

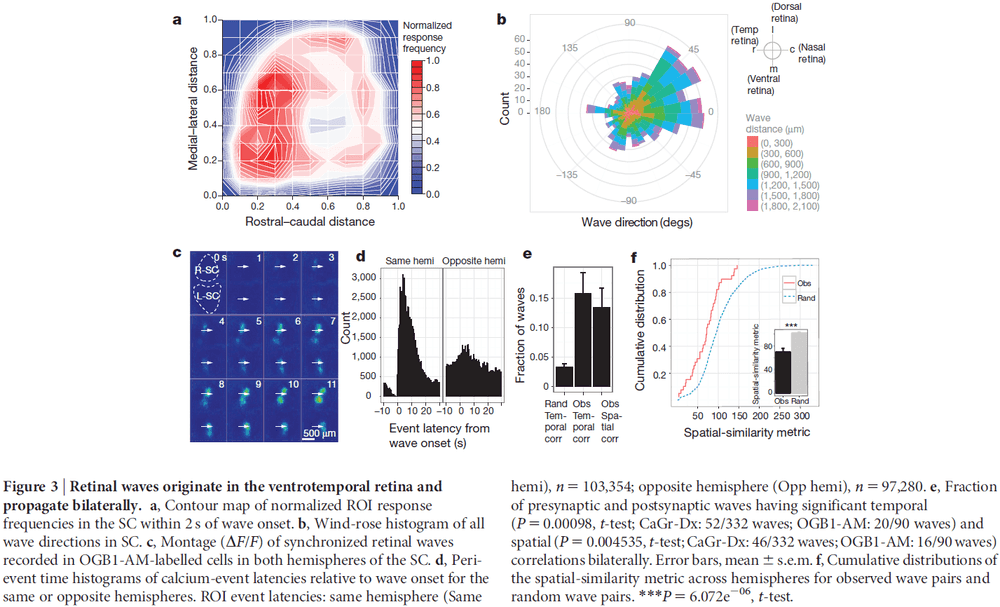

- Spontaneous retinal waves occur in vivo

- The most superficial layer of the mouse SC, the stratum griseum superficiale (SGS), receives retinotopically mapped terminal input from all RGCs and is accessible to imaging during development.

- By injecting a calcium indicator into the retina of neonatal mice, we can record directly from RGCs and their terminals in the SC in vivo.

- Calcium imaging of the RGC terminals revealed spontaneous waves of activity propagating through the SC of neonatal mice.

- Surprisingly, in vivo waves propagated over a much greater proportion of the SC area than was expected based on previous in vitro studies.