Your Brain Is a Time Machine

By Dean BuonomanoMay 30, 2021 ⋅ 23 min read ⋅ Books

Part I: Brain Time

Chapter 1: Flavors of Time

- Although time is one of the most common nouns in the English language, there’s no consensus on its definition.

- Questions of time

- Is time a dimension or a moment?

- Why does it appear to flow in one direction?

- What does it mean to feel the passage of time?

- How does the brain tell time?

- The goal of this book is to explore and to try to answer these questions.

- We must acknowledge that our ability to explore time is limited by the nature of the organ asking them.

- Time is more complicated than space for the human brain to understand.

- We know brains have a highly complex internal map of space.

- Review of place cells.

- Animals and see and hear space, but time is different.

- Science is much simpler if we ignore time.

- By studying motion, or how the position of objects change over time, we started incorporating time into science.

- The ultimate mathematical tool to capture how things change over time is calculus.

- Biology grew to incorporate time in the form of evolution and dynamics.

- Darwin played the role of Galileo for biology: he saw that species were in constant motion, changing to adapt to the environment.

- In neuroscience, the problem of time has been overlooked.

- E.g. The Principles of Neural Science textbook doesn’t have time in its index.

- How does the brain store memories?

- Memory is inherently entwined with time.

- Information about the past is only useful if it allows us to anticipate the future.

- There’s been an increasing focus on time in neuroscience and psychology.

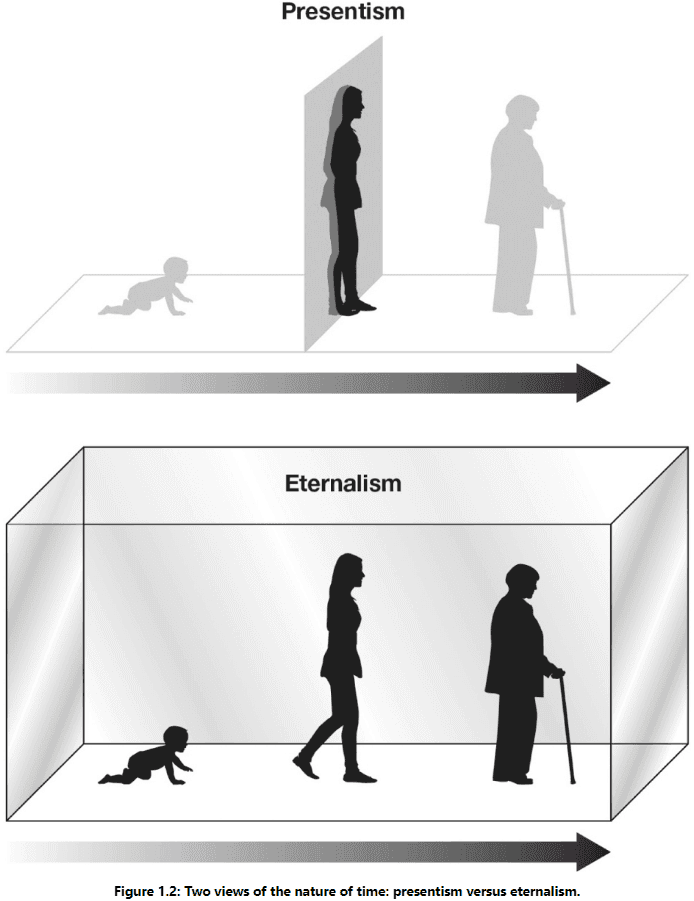

- Two philosophical theories of time

- Presentism: argues that only the present is real.

- Eternalism: argues that the past and future are equal to the present.

- In presentism, time travel is impossible because you can’t travel to a time that doesn’t exist regardless of the laws of physics.

- In eternalism, time travel is possible but may not be achievable due to impossible requirements such as negative mass and infinite energy.

- Presentism matches our intuition of time and neuroscientists are implicitly presentists.

- However, physicists and philosophers are eternalists and believe that the past, present, and future have been laid out.

- The clash between neuroscience and physics is if all moments of time are equally real, and all events in our past and future and eternally embedded within the block universe, then our perception of the flow of time must be an illusion.

- That is, if time is already predetermined, then time can’t be flowing or passing in the normal sense of those words.

- Any discussion of time is inevitably muddled by the many meanings of the word “time”.

- E.g. “Her talk on the nature of time ended on time, but seemed to drag on for a long time.”

- This sentence mixes three definitions of time

- Natural time: the concept of time as a medium or dimension.

- Clock time: time as what clocks measure.

- Subjective time: our conscious sense of time; the subjective feeling of the passage of time and how much of it has passed.

- What exactly is a clock?

- Clock: a device that undergoes a reproducible change and offers a way to quantify these changes.

- E.g. Swings of a pendulum, vibrations of a quartz crystal, or the amount of radioisotopes of carbon in a fossil sample.

- Clock time is a local measure of time that’s neither universal nor absolute.

- Like all subjective experiences, subjective time is made up by the brain and doesn’t exist outside the skull.

- Analogous to how the perception of color allows us to experience a physical property of visible light (wavelength), our perception of time allows us to experience both natural and clock time.

- The brain is a time machine that lets us both experience present time, but to also project ourselves backwards and forwards in time.

- Our unique ability to both grasp the concept of time and to peer into the distant past/future is both a blessing and a curse.

- We have both more control over the future, but also the realization that our own time is finite.

Chapter2: The Best Time Machine You’ll Ever Own

- Time travel wasn’t really mentioned or used in most of human history up until late nineteen century.

- You are the best time machine that has ever been built.

- The brain doesn’t allow us to physically travel through time, but it is a time machine.

- Four justifications

- The brain is a machine that remembers the past to predict the future.

- The degree to which animals succeed in predicting the future translates into the evolutionary currency of survival and reproduction.

- The brain is, at its core, a prediction or anticipation machine.

- To predict the future, the brain stores a vast amount of information in the form of memories.

- The brain is a machine that tells time.

- The brain is trained to recognize and generate temporal patterns.

- E.g. Rhythms and motor control.

- Telling time is a critical component of predicting the future.

- E.g. It isn’t enough to know that it’ll rain. We should also know when it’ll rain.

- Every aspect of behavior and cognition requires the ability to tell time.

- The brain is a machine that creates the sense of time.

- Unlike vision or hearing, we don’t have a sensory organ for time.

- The brain creates the feeling of the passage of time.

- Like most subjective experiences, our sense of time is vulnerable to illusions and distortions.

- The brain allows us to mentally travel back and forth in time.

- We can engage in mental time travel by either recalling our memories or imagining the future.

- “The best way to predict the future is to create it”.

- The brain is a machine that remembers the past to predict the future.

- We learn to relate words to real-life objects by learning their temporal relationship.

- E.g. If a cat appears and our parents mention the word “cat” around it, then we learn to associate that animal with that name.

- Review of classical conditioning and how its the fundamental algorithm to predict what happens next.

- Maybe the size invariance problem is also solved by temporal contiguity.

- E.g. If the same object changes shape but is always in view, we convert the size in the invariance problem into a temporal one.

- Classical conditioning is highly sensitive to the interval between the events.

- E.g. The longer the interval between events, the harder it is to detect the connection.

- So, classical conditioning is a shortsighted form of learning.

- In general, we’re temporally myopic.

- In most languages, it’s easier to understand the sentence if the events are stated in order.

- E.g. “She smiled before opening the gift” versus “Before opening the gift, she smiled”.

- Review of neurons, synapses, presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons, STDP.

- The brain must wire itself, although genetics does help a bit.

- STDP is like a neural cause-and-effect detector.

- Review of sound localization.

- Telling time allows us to tell space.

- Telling time is different from the process of consciously perceiving the passage of time.

- The brain is both an anticipation machine and a machine that tells time.

- The range it can quantify time over is large, from tiny differences in sound arrival time to the ability to anticipate seasons.

- But how does the brain tell time?

- The brain uses different clocks for different time scales. This is the multiple clock principle.

Chapter 3: Day and Night

- Review of the circadian clock that controls our day-night cycle.

- The circadian clock is impressively precise at one percent deviation. In other words, it can maintain the same cycle with only a one percent change in start/end time.

- Review of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) and its role as the master circadian clock.

- Lesion and transplant studies support the hypothesis that the SCN governs our circadian clock.

- Tracking and anticipating the light and temperature fluctuations caused by the rotation of the Earth is so important that almost all forms of life have circadian clocks.

- Many cells have their own private circadian rhythm that’s implemented by the concentration of proteins rising and falling in a period of approximately 24 hours.

- Why would bacteria care what time it is?

- One of the driving forces for the evolution of circadian clocks was the adaptive coordination of cellular functions with cycles of light and dark.

- It isn’t enough to have a clock, but the clock must also resonate with the cycle of the environment to provide an evolutionary advantage.

- A circadian clock is implemented using a negative feedback loop.

- DNA encodes for a protein and that protein stops the production of itself. This will oscillate at a cycle matching the circadian rhythm.

- All cells have this circadian clock but they’re synced using the SCN, the master circadian clock.

- But how does the SCN know the correct time?

- It uses signals from the environment such as light. There are special ganglion cells in your retina that specifically send the light level to the SCN that’s independent of sight.

- The coordination of circadian clocks within our body is critical to being healthy.

- E.g. The pancreas increases insulin production before a meal but if the timing is off, you become at risk for diabetes due to insulin not being synced with increases in blood sugar.

- Are different clocks used for different time scales? Or is it the same clock?

- Studies show that we have distinct circuits devoted to telling time across different scales.

- E.g. Lesions to the SCN don’t change our ability to time events on the scale of seconds.

- This also matches with our understanding of the mechanism behind the circadian clock, as the biochemistry of protein transcription is too slow for measuring seconds.

- The timing devices within our body and brain are unlike man-made clocks.

- The same watch can track seconds, minutes, and years, but organisms need multiple clocks to track each of these units of time.

- While the brain does track time, we don’t feel it like we feel the pain of subbing our foot.

- The brain has other means to judge the passage of time.

- Where does our subjective sense of time’s passage come from?

Chapter 4: The Sixth Sense

- During intense situations, our subjective sense of time can be radically changed.

- E.g. Things going into slow motion during a car accident or during an intense competition like a sports finale.

- People generally overestimate the duration of intense events, but this also happens for mundane events such as waiting in line at the grocery store.

- Our subjective sense of time is actually quite inaccurate.

- Boring activities can create a feeling of chronostasis.

- Chronostasis: the sensation that time is standing still.

- Exciting or engaging events have the opposite effect where time seems to have vaporized.

- E.g. Being immersed in your favorite hobby or experiencing how time flies by while having fun.

- Two types of timing

- Prospective: determining the passage of time starting from the present into the future.

- Retrospective: determining the passage of time from the past until the present.

- We engage in both types of timing everyday.

- E.g. If someone asks you to remind them in five minutes versus if someone left five minutes ago and someone else asks how long ago since they left.

- The brain uses different mechanisms for each type of timing.

- Prospective timing uses the brain’s stopwatch, retrospective timing uses the brain’s memories.

- E.g. “In general, a time filled with varied and interesting experiences seems short in passing, but long as we look back.” - William James

- Retrospectively judging time uses the number of events stored in memory as a judge or proxy for duration.

- The intimate relationship between memory and retrospective timing is illustrated by patients that can’t form new long-term memories.

- Those patients always live in the now, unable to escape into the past.

- While retrospective timing is dominated by memory, prospective timing is dominated by cognitive load.

- E.g. The more complex or challenging a task, the shorter the estimated time elapsed.

- The opposite can happen with retrospective timing, but the effect isn’t as strong.

- It’s as if when we shift our attention, some internal timer within our brain ticks faster.

- Humans report that time slows down under the influence of cannabis because the hypothetical internal clock is running fast.

- The scientific literature on the effect of drugs on time perception indicates that there’s no single neurotransmitter that controls our perception of time.

- Possible causes of the slow-motion effect

- Overclocking the brain. Probably not.

- Hypermemory. Some contribution.

- Metaillusion. Most probable.

- A subjective experience, whether color, sound, or the passage of time are, in essence, illusions.

- E.g. The pain of stubbing your toe is produced within the brain, yet amazingly, it isn’t perceived as occurring within the brain; rather, it’s projected out to the point in space where your toe happens to be.

- The illusion is unveiled by phantom-limb syndrome.

- Our normal sense of time is a mental construct, one that seems to have different speed settings.

- Just like how the brain can project the feeling of location of our limbs to different points in space, it seems to also be able to differentiate events as quickly or slowly.

- That is, our subjective experience of time as fast or slow may be dissociated from the rate the brain is processing information or the brain’s internal clock speed.

- Ultimately, our perception of the speed of time is a somewhat arbitrary setting on top of consciousness.

- E.g. The speed that people talk varies, why not their perception of time too. You can mentally replay a song quickly or slowly.

- Our ability to execute the same action at different speeds is an important feature of the motor system.

- E.g. Slowing down speech when talking to a baby or speeding it up at the end of a lecture. Slowing down handwriting to make it look prettier, or speeding it up during a lecture to catch everything the professor is saying.

- Our sense of time isn’t a true sense like vision or touch as there’s no organ for time.

- All subjective experiences are illusions created by the brain for the brain.

Chapter 5: Patterns in Time

- Phoneme: the smallest unit of speech.

- Different languages use different sets of phonemes, but the collection of all possible phonemes is known and studied by linguists.

- Review of voice-onset time and prosody.

- Motherese (baby talk): a change in speech patterns when talking to infants where the parent slows down their speech.

- Time is to speech and music recognition as space is to visual object recognition.

- They require solving a hierarchy of embedded temporal problem and this requires some sort of memory.

- In object recognition, all of the features are simultaneously present but the relevant features of speech and music require integration across time.

- We can think of frequency as spatial information because to the brain, it’s the spatial location along the basilar membrane in the cochlear.

- Experiments suggest that practice does improve the quality of the timers within our brain.

- However, this improvement only occurred for the intervals that the participants trained on and not for other intervals. In other words, the training doesn’t generalize.

- This suggests that the brain doesn’t have any sort of master stopwatch mechanism that can time any and all intervals.

- A surprising result is that most animals, except for birds, can’t synchronous pressing a button to match a beat.

- Not only do animals not match our musical proclivities, they also seem to lack the sensory-motor skills necessary to synchronize their movements with a periodic stimulus.

- Why are we and birds the exception?

- Few animals learn to produce vocalizations as a result of experience and social interaction.

- This requires that the brain listen to sounds and then figure out how to reproduce them using the vocal chords and oral muscles.

- It’s been proposed that the same brain wiring that allowed animals to learn vocal communication also underlies the apparently much simpler act of following the beat of a song.

- One cool experiment was when researchers slowed down the bird brain area that times its song by cooling it down. The result was that the birds sang at a slower rate.

- This implies that song timing is caused by the activity patterns of neurons within that brain area.

- Multiple results suggest that while specific circuits within the brain are responsible for certain types of timing, most circuits are intrinsically able to tell time if needed.

- E.g. Auditory circuits for music, visual circuits for Morse code, and the basal ganglia for motor control.

- We should view timing, in the range of hundreds of milliseconds, not as computations performed by specialized circuits, but as an intrinsic property of neural circuits.

- People often ask if there are any neurobiological disorders that result in the loss of the ability to tell time.

- The answer is no. There are no known cases that result in people losing their ability to appreciate the rhythm of music, and reproduce intervals in the range of seconds, and blink in response to a tone. In other words, people can’t lose their short-term memory.

- There’s a Goldilocks zone for timing in the range of milliseconds to a few seconds.

- In this range, we can appreciate speech and music. We can make sense of both the forest and the trees.

- Without the ability to parse complex temporal patterns, we wouldn’t be able to engage in two signature abilities of the human species: speech and music.

- But how does the brain parse out this pattern? How does the brain measure the duration of a syllable or the tempo of a song?

Chapter 6: Time, Neural Dynamics, and Chaos

- Man-made clocks rely on a simple principle: count the number of cycles of a repeating phenomenon to count time.

- The sophistication of the phenomenon varies widely.

- E.g. Swinging of a pendulum, vibration of a quartz crystal, or cycles of EM radiation.

- It’s tempting to say that the brain also uses a similar principle to tell time.

- Perhaps too tempting.

- We know that neurons can oscillate, but the crux of the problem is that they don’t count such oscillations to tell time.

- E.g. Oscillating brain waves, breathing, walking, heartbeat, circadian clocks.

- The circuits controlling breathing have no idea if they’ve generated one thousand, one million, or one billion breathing cycles.

- There’s little experimental support for the internal clock model of timing.

- Spatiotemporal pattern: a spatial pattern that changes over time.

- Short-term synaptic plasticity: use-dependent changes in synaptic strength.

- Much like how the diameter of a ripple in a pond contains information about how much time has elapsed since the raindrop fell, the strength of a synapse at any given moment contains temporal information about how long ago that synapse was last used.

- Maybe this is how the brain tells time on the order of hundreds of milliseconds; using short-term synaptic plasticity.

- Population clock: that each moment of time is represented by a large subpopulation of active neurons.

- If spatiotemporal patterns of neural activity within a population of neurons are to be used as a timer, they must repeat the same pattern again and again in response to the same context and stimulus.

- Experimental evidence supports the repetition of the spatiotemporal pattern, but the mechanism is unknown.

- Review of chaotic dynamical systems.

- It’s possible to control the chaos in recurrent neural networks by tuning the strength of the synaptic connections.

- To solve temporal problems, the brain uses a set of interrelated timing mechanisms distributed across its circuits.

- The clocks within the brain bear little resemblance to the clocks devised by the brain.

- All neurons in the brain tell time.

Part II: The Physical and Mental Nature of Time

Chapter 7: Keeping Time

- Like how we’ve built microscopes and telescopes to see outside the limits of our vision, we’ve built temporal microscopes and telescopes to capture time scales outside those the brain can measure.

- E.g. Calendars, atomic clocks, carbon dating.

- Physics is, in part, an outcome of our desire to tell time.

- Much like how the brain has different mechanisms to tell time prospectively and retrospectively, we’ve developed different ways to tell times backwards and forwards.

- This chapter recounts the history of clock development.

- One of the main ways for telling time backwards is radiodating.

- Radiodating: using the current amount of a radioactive element and its half life to work out when that organism/item was created.

- This was used to settle the debate on whether new neurons are created in adult human brains.

- If new neurons are created, then we’d expect them to pick up more carbon 14 isotopes and that’s exactly what we see in dead brains.

- Carbon 14 is used as the measure because nuclear bombs release it and it’s picked up by organisms. So if new neurons aren’t created, then we wouldn’t see any carbon 14 in a dead person’s brain.

- This strange intersection between neuroscience and nuclear proliferation was instrumental in overturning our belief that new neurons are never formed in adult humans.

- The ability to tell time using radioactive decay lies in the statistics of the population.

- E.g. The larger the initial number of radioactive neurons, the more accurate our estimate of time.

- Clocks aren’t just a means to tell time, but to synchronize the actions of people.

- Whether man-made or biological, changes in temperature pose one of the greatest challenges to high-performance clocks.

- This is because thermal fluctuations can interfere with our ability to measure cycles. Is the cycle due to an actual cycle or due to a thermal fluctuation that looks like a cycle?

- Interestingly, the best way to measure space is with a clock.

- This is because clocks are more accurate than distance measuring devices; we can measure time more precisely and accurately than space.

- E.g. The length of a meter is actually defined by the time light takes to travel a period of time.

- Another use of clocks is that they parcel our lives into ever smaller units of time.

- However, our ability to measure time hasn’t brought us closer to understanding the nature of time.

- Why does time only flow on one direction?

- Are the past and future fundamentally different from the present?

Chapter 8: Time: What the Hell Is It?

- Why are we so good at recognizing faces but so bad at mental math?

- The building blocks of any computational device, whether it be the brain or a digital computer, shapes which tasks it’s well suited to perform.

- We’re bad at mental math because neurons just didn’t evolve with the selective pressure to do math. They lack the speed and precision of transistors that form our digital computers.

- In the face of these facts, we should also ask to what extent the brain’s inherent limitations and biases constrain the progress of science.

- How does the brain’s architecture shape our ability to answer questions that it didn’t evolve to address?

- Among the many things the brain certainly didn’t evolve to understand was the brain itself. Another is the nature of time.

- We’ve been incredibly successful at measuring time, but what exactly are we measuring?

- Presentism and eternalism capture the two main views.

- Language assumes an inherent presentist perspective due to its use of tenses.

- One theory that advocates for both, the evolving block universe theory, argues that the present is a wave front that progressively freezes the undetermined future into the unchanging past.

- Clock time can be seen as a convention by which we standardize change.

- Maybe time is a measure of change or a measure of cycles (repeated and consistent change).

- The debates and controversies about time is a symptom of the fact that there is no consensus as to what time actually is.

- However, physics and philosophy favor eternalism, but it doesn’t match our subjective sense of time.

- Two arguments for eternalism

- According to physics, the now is as arbitrary a moment in time as the here is a point in space.

- Special relativity implies that all moments in time are laid out.

- The laws of physics don’t give any special meaning to the direction of time.

- The standard answer to the mystery of time’s arrow is the second law of thermodynamics.

- The entropic arrow of time seems to provide a satisfying answer, but it isn’t so much an arrow.

- It’s only an arrow because we’ve assumed that the universe started in a low entropy state.

Chapter 9: The Spatialization of Time in Physics

- Review of Einstein’s special relativity.

- Velocity is always defined in relation to something else, a frame a reference.

- There is no correct or absolute frame of reference except for the speed of light.

- Together, that velocity depends on the frame of refence and that there is no absolute frame of reference, it follows that there’s no absolute time.

- The price to be paid for the speed of light being absolute is that space and time can’t be.

- Clock time is always measured by change, and change is a local phenomenon.

- Yet despite the persuasive arguments in favor of eternalism, it fails to account for the observation that the present is special is us and that time does flow.

- It’s been hypothesized that our access to multiple moments of time, our memories, somehow leads to our subjective sense of the passage of time.

- Or maybe the flow of time is an illusion created by our brains.

- However, the nervous system is highly attuned to the laws of physics.

- E.g. We have an intuitive sense of gravity and of objects such as object permanence.

- Review of qualia.

- Qualia are illusions in the sense that they don’t exist in the external world, but they do exist for us and are based in real physical phenomena.

- E.g. There’s nothing blue about light at 470 nm.

- To grasp the potential adaptive value of our subjective experiences, let’s return to the most intimate illusion the brain bestows upon the mind: body awareness.

- If you feel pain, it isn’t perceived as occurring within the brain, but is somehow projected out into the external world even though it occurs in the brain.

- Two arguments against eternalism

- Evolution

- Much like how our conscious perceptions of color and pain are adaptive because they correlate with important events in the external world, perhaps our sense of the flow of time is adaptive because it correlates with events unfolding in the world.

- Maybe the flow of time helps us better predict the future.

- Consciousness and neural dynamics

- Is consciousness something that can only exist across time slices?

- Evolution

- Do the laws of physics need to adapt to explain our conscious experience of time? Or does neuroscience need to figure out a way to explain away our subjective sense of the flow of time?

- Is the flow of time a fiction created by the mind or something that eludes physics?

Chapter 10: The Spatialization of Time in Neuroscience

- Piaget (famous psychologist) and many others found that children come to understand time only after they understand the concepts of space and speed.

- It may be that our confusing and complex language of time makes it difficult for children to grasp.

- E.g. 12 vs 24 hour time, modular math, and inconsistent month days.

- The theory that our ability to grasp the concept of time was co-opted from the neural circuits that evolved to navigate, represent, and understand space.

- We often use spatial terms to talk about time.

- E.g. A short video or he was studying for a long time. I’m looking forward to your birthday. The day flew by.

- When it comes to statements about moving in space, there’s always some standard reference, usually the ground.

- When it comes to statements about moving in time, there’s no standard frame of reference.

- Kappa effect: that the distance between two events has a profound effect on people’s judgments of the amount of time between them.

- E.g. If a dot on the left is flashed and then a dot on the right, and if the distance between the dots is greater, then people estimate that the time between flashes is longer.

- In other words, people seem to use distance as a proxy for time even if it isn’t accurate.

- The reverse was also shown to be true (called the tau effect).

- The kappa effect seems to suggest that the clock within the brain that’s responsible for timing on the scale of seconds is somehow influenced by the neural circuits responsible for estimating distances.

- Or maybe that the brain has a shared magnitude system as temporal judgments aren’t only affected by distance, they’re also affected by the brightness or size of a stimulus.

- It was also found that reporting short durations is more natural with your left hand than with your right hand.

- Why? There might be a mental timeline laid out from left to right within your mental circuits.

- Overall, we don’t yet understand how neurons in the brain represent or store spatial and temporal magnitudes. Yet based on linguistic, psychophysical, and neurophysiological evidence, it’s clear that space and time are intertwined in the brain.

- Parallels between the neuroscience and physics of time

- Time is relative and moves at different speeds.

- Space and time aren’t independent.

- Relativity of simultaneity.

- From the day you were born, your visual system has been sampling the statistics of the world.

- E.g. Concave-Convex illusion due to light generally coming from above.

- The human mind does indeed inhabit an eternalist universe, mentally speaking, and not only do the past and future exist, but they can be travelled to.

Chapter 11: Mental Time Travel

- Mental time travel: the ability to project ourselves into the past or future.

- E.g. Replaying memories or daydreaming about the future.

- We can revisit the past and previsit the future.

- Review of semantic (knowledge) and episodic (event) memory. It’s the difference between knowing and remembering.

- It’s often overlooked that semantic memory is absent of a time stamp, but episodic memory has one.

- So episodic memory has order (in the form of a timeline) while semantic memory doesn’t.

- Both episodic memory and mentally projecting ourselves into the future require semantic memory.

- It’d be difficult to simulate being on the beach without knowledge of how sand, water, and wind work.

- Semantic memories may serve as the infrastructure to lay down episodic memories, which is supported by developmental studies.

- Lesion studies support the theory that mentally traveling backwards or forwards in time relies, in part, on the same cognitive capacities we use to store and reconstruct autobiographical information about the past, namely the hippocampus.

- Do other animals also mentally time travel?

- Telling time isn’t the same as thinking about the future.

- Most examples of apparent long-term planning in animals actually seem to be hardwired instincts.

- E.g. A falling rock doesn’t know the law of gravity much like a squirrel stashing nuts doesn’t know about winter.

- However, corvids and great apes seem to display foresight, which suggests that they do perform mental time travel. But this research is still controversial.

- Different people and cultures vary dramatically in how much thought and effort they apply towards the future and how far ahead they mentally travel into the future.

- We engage in a one-way conversation with future generations.

- Semantic and episodic memories stored within our neural circuits are ultimately a recipe for survival.

- Without future-driven behaviors and cross-generational memories, modern technology, culture, and science wouldn’t exist.

- However, despite our ability to see the future, we often struggle to do something about it.

- Review of immediate and delayed gratification, and encephalization quotient.

- The prefrontal cortex contributes to our ability to make long-term plans, delay gratification, and engage in mental time travel.

- However, it would be naïve to say that that’s where mental time travel happens as it’s a complex task that require memory, imagination, simulation, and judgement.

- Mental time travel relies on a collection of different brain areas working together.

- The temporal in temporal lobe doesn’t refer to time, but to the temples or the temporal bone of the skull.

- The paradox of mental time travel is that it’s both the solution and cause of all our troubles.

Chapter 12: Consciousness: Binding the Past and the Future

- What we experience is correlated with the external world, but it isn’t the complete picture.

- Sometimes, we see fictions imposed upon the mind from within.

- E.g. Colors, hallucinations, dreams, infrared light, our retina’s blind spot.

- The feeling of the passage of time, our perception of change, is also a mental construct.

- Our brains don’t provide a linear progression or play-by-play account of the raw sensory events unfolding in our world.

- E.g. When you listen to speech, you don’t hear the syllables and air compression waves, you hear words and their meaning.

- Vision is partially suppressed during saccades and blinks, providing the illusion of the flow of time.

- The difference in speed of lightening and thunder, due to the difference in speed of light and sound, shows how the brain merges both sensory modalities to create a uniform perception.

- E.g. We don’t first see someone talking and then hear it, we experience it simultaneously even though light is faster than sound.

- We don’t consciously register the delay between visual and auditory signals because the unconscious brain integrates visual and auditory information into a single unified percept.

- The time span during this integration is called the temporal window of integration.

- Within this window, the brain considers the auditory and visual events to be simultaneous.

- E.g. Speech has a temporal window of 100 ms but the window is asymmetric. If the sound comes 50 ms before sight, we notice. If it comes after, we don’t.

- The temporal window isn’t set in stone and can adapt to the incoming data.

- The most compelling case of how consciousness reflects a temporally edited account of reality is that later sensory events can actually alter earlier ones.

- E.g. Cutaneous rabbit illusion: where two taps to the wrist and two taps to the elbow within 100 ms results in feeling four taps hopping along your arm instead of the predicted two taps to each location.

- The location of later stimuli alters your conscious perception of the location of the earlier ones.

- So, consciousness can’t be a uniform and continuous account of the flow of time.

- Review of the neural correlates of consciousness.

- “Not only do we consciously perceive only a very small portion of the sensory signals that we receive, but we do so with a time lag of 300 ms.” - Stanislas Dehaene

- When we hear ambiguous stimuli, the unconscious brain presumably waits for an unambiguous interpretation before crafting a conscious precept.

- E.g. The top stopped spinning versus The top of the mountain. The brain initiates both meanings of the word “top” before the sentence ends, and then selects the one that best matches the context.

- Maybe free will is just a feeling.

- Maybe the feeling of free will provides the conviction that we’re in control of our destiny, and thus the impetus to take charge and make the long-term, future-oriented, actions necessary for survival.

- There’s no unified consensus about the nature of time.

- Presumably, some functions the brain performs generate subjective experiences because consciousness affords a selective advantage to these processes.

- So what selective advantage does the subjective experience of time provide?

- If we’re to unwisely summarize the function of the brain in three words: anticipate the future.

- The brain tells time, remembers, and can imagine to predict and prepare for the future.

- The brain has a variety of mechanisms to tell time across different scales.

- Why are the clocks within the human brain so different from those devised by the human brain?

- The answer comes down to the building blocks of both types of clocks; one is built on biological systems, the other is built on physical systems.