Connectome

By Sebastian SeungJune 15, 2019 ⋅ 11 min read ⋅ Books

Introduction

- Analogy of the brain as a forest and neurons as the trees. Analogy shows how messy but organized the brain is.

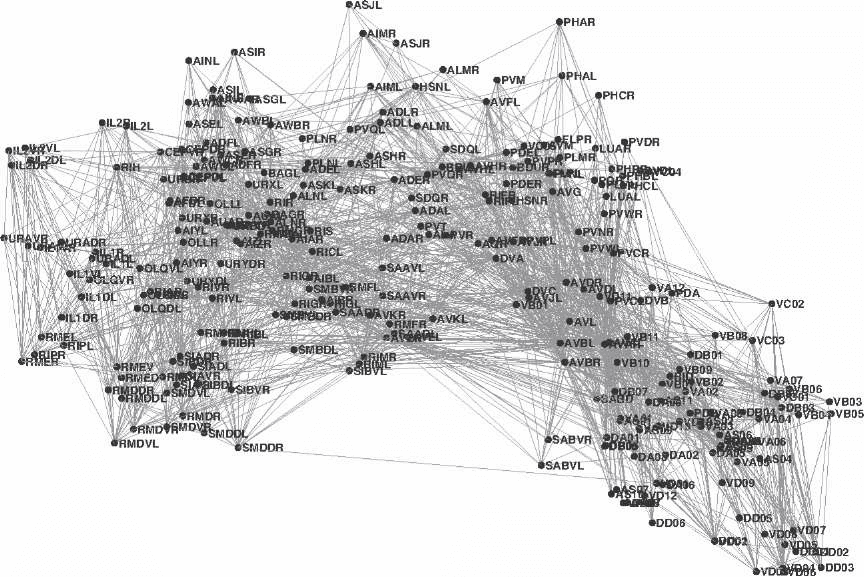

- Connectome: a wiring diagram of the brain. It’s a map of all connections for all neurons in the brain and body.

- The book’s argument is that minds differ because connectomes differ.

- An alternative argument is that minds differ because genomes differ but genomes can’t explain how your brain becomes what it is now.

- E.g Your genome doesn’t store your memories and identical genetics (twins) doesn’t mean you behave the same.

- The brain is able to learn and go beyond the instincts programmed by its genes.

- Neurons have four abilities (the four R’s)

- Reweigh

- Reconnect

- Rewire

- Regenerate

- Both genes and experiences shape the connectome. Just like how nature and nurture does.

- You are more than your genes. You are your connectome.

- A compatible view is that you are the activity of your neurons.

- The connectome defines the pathways along which neural activity can flow; the streambed of consciousness.

- The metaphor is fitting as over time, the streambed directs the stream, while the stream slowly shapes the streambed. Similar to how neural activity over time changes the connectome and the connectome changes the possible neural activity.

- There are two selves, the stream, which is fast and changing, and the streambed, which is slow and stable.

- This book focuses on the streambed, the connectome.

Part I: Does Size Matter?

Chapter 1: Genius and Madness

- The hypothesis is that different brains result in different minds.

- We’ve learned that brain size is weakly correlated with IQ.

- Aphasia: loss of language ability.

- Broca’s aphasia: loss of speech.

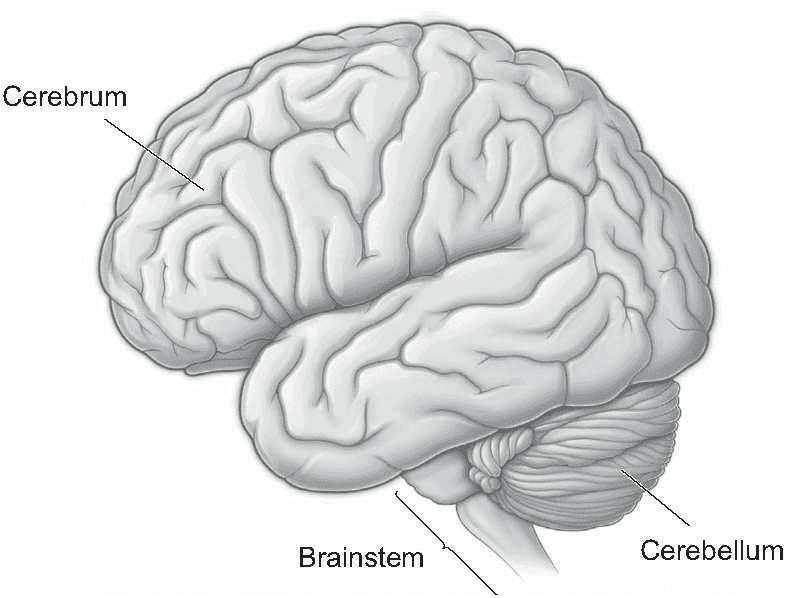

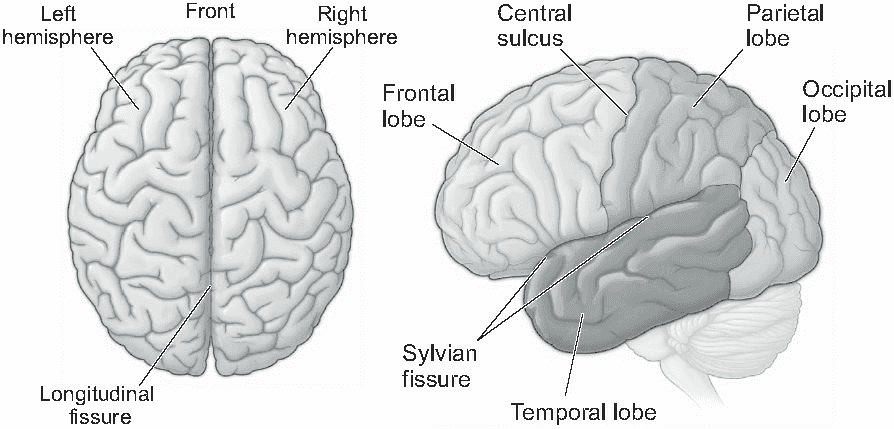

- Cortical/cerebral localizationism: the localizing of a mental function to particular brain regains.

- Cerebral lateralization: the idea that mental functions are located in either the left or right hemisphere.

- Double dissociation: when changing one aspect doesn’t affect another and vice versa.

- The mind is modular and is divided into parts.

- The rest of this chapter discusses mental disorders such as autism and schizophrenia.

Chapter 2: Border Disputes

- How does the brain change when we learn to behave in a new way?

- Selection bias explains why people go into the field that they are good at. If you weren’t good in a field, you would lose motivation to continue in that field.

- Can a cortical area acquire a new function after brain injury?

- There’s evidence for this in children with brain damage. Children that lose a part of their brain are able to compensate for that loss by having the remaining brain areas take over the lost functions.

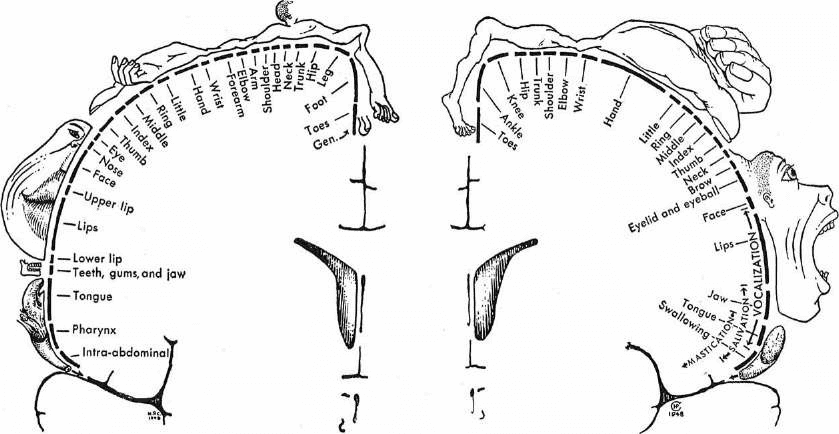

- There is a map dividing the cortex into areas with distinct functions but the map can be redrawn as evident by neuroplasticity.

- Maybe phantom limbs are caused by a remapping of the cortex.

- This was confirmed by V.S. Ramachandran where he found that surrounding brain areas encroach upon the unused brain area.

- Why isn’t the correlation between the size of a cortical area and its function more strongly correlated?

- E.g. The coefficient of muscle size to muscle strength is 0.7 to 0.9.

- This contrasts with the brain’s low coefficient of size to function.

- Why are size and function so closely related for muscles but not for brains?

- Think of muscles as a simple factory where each worker does the same job. Scaling the number of workers scales the output proportionally.

- However, brains are more like complex factories where each worker does a different, smaller job and they have to collaborate to complete the job.

- Each neuron is a worker that performs a small job and they cooperate in intricate ways to carry out mental functions.

- That’s why performance depends less on the number of neurons and more on how they’re organized.

- This isn’t quite true as Suzana Herculano-Houzel found that our primate brain has been increasing in the number of neurons and size over the course of evolution.

Part II: Connectionism

Chapter 3: No Neuron Is an Island

- This chapter starts with an introduction to neurotransmitters.

- We should distinguish between the medium and the message. The medium being chemical signals and the message being unknown to current neuroscience.

- Chemical signals, such as neurotransmitters, are poor messengers due to being: slow, imprecise in targeting, and imprecise in timing.

- Chemical signals have plenty of disadvantages but the brain can work around them.

- The brain works around slowness by reducing the distance across the synaptic cleft.

- The brain works around imprecise targeting by recycling the the chemical before it has a chance to spread and cross-talk.

- The brain works around imprecise timing by recycling the neurotransmitters quickly.

- Properties of chemical synaptic communication

- Speed

- Specificity

- Temporal precision

- Electrical signals in different neurites interfere with each other very little just like insulated wires.

- Transmission of signals between neurites only occurs at specific junctions called synapses.

- Spikes are useful for long range communication because it can be easily distinguished from noise and interference.

- Synapse communication is one-way, which makes neuron communication one-way.

- Synapses impose this directionality onto neurites.

- Similar to how the valves in veins impose directionality, synapses impose directionality onto neural pathways.

- Synapses don’t simply relay spikes to the next neuron as almost all synapses are weak.

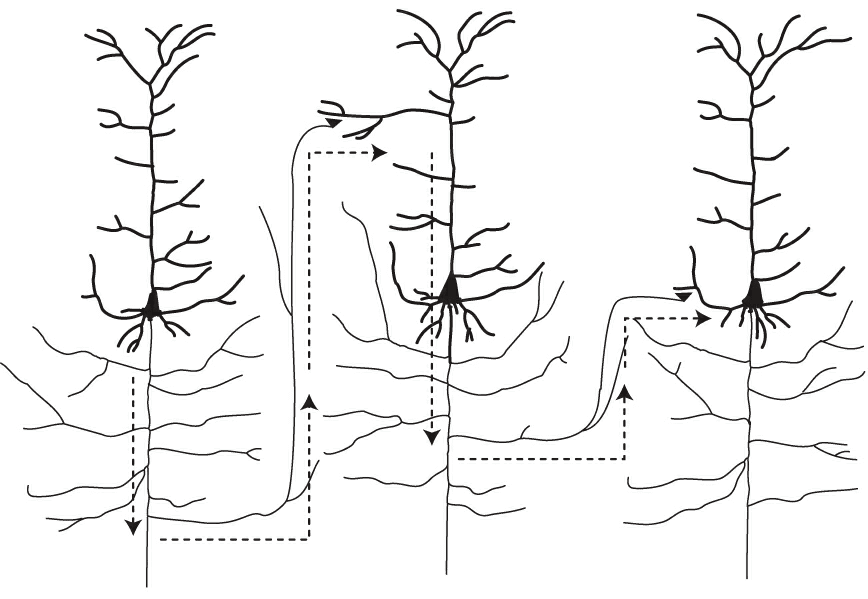

- Axons usually diverge but dendrites usually converge.

- The cell body collects currents from many synapses converging onto its dendrites.

- Even though one spike might be too weak to get through a synapse, multiple converging spikes could.

- This is known as the “weighted voting model” of a neuron.

- Introduction to excitatory and inhibitory synapses.

- Neurons, like synapses, can be classified as either excitatory or inhibitory. A neuron cannot excite some neurons but inhibit others, regardless of time.

- So neurons are all-or-none of either excitatory or inhibitory.

- If an excitatory neuron hears many “yes” votes, then it votes “yes”.

- If an inhibitory neuron hears many “yes” votes, then it votes “no”.

- Failing to spike is just as important to neural function as spiking.

- Spikes have two functions

- Communication via axons.

- Decision-making via the cell body.

- Both functions have different, and sometimes conflicting, goals. One tries to preserve information while the other tries to ignore irrelevant information.

- So neurons may transmit some information but they also throw away a lot of information.

- “Do you know why I’m so smart? It’s because I’m so good at forgetting the right things.”

Chapter 4: Neurons All the Way Down

- Neurons are wired into a network with a hierarchical organization.

- A neuron that detects a whole receives excitatory synapses from neurons that detect its parts.

- The function of a neuron depends on its output connections, not only its input connections.

- The function of a neuron is defined by its connections with other neurons.

- Ideas are represented by neurons, associations of ideas by connections between neurons, and a memory by a cell assembly or a synaptic chain.

Chapter 5: The Assembly of Memories

- Synapses can strengthen and weaken by reweighing in the process of getting bigger or smaller.

- Synapses can also be created and eliminated in a process called reconnection.

- Both reweighing and reconnection change the connectome.

- There are two ways to explain the neuronal basis of forming an association.

- If two neurons are repeatedly activated simultaneously, then the connections between them are strengthened in both directions.

- If two neurons are repeatedly activated sequentially, the connection from the first to second is strengthened.

- The brain uses sparse connectivity where only a small fraction of possible connections are made.

- This is due to a size constraint on the brain; there isn’t enough space for all of the connections.

- Maybe neurons start off with random connections and prune them afterwards by only letting the strong connections survive.

- Synapse elimination refines connectivity.

- The brain might randomly create new synapses to continually renew its potential for learning while eliminating the synapses that aren’t useful.

- There’s good evidence that retention of memories over long periods doesn’t require neural activity.

- E.g. People recovering from being brain dead can still remember past events even though their brain wasn’t firing any spikes.

- Dual-trace theory of memory

- Persistent spiking is the trace of short-term memory.

- Persistent connections are the trace of long-term memory.

- To store information for long periods of time, the brain transfers it from activity to connections.

- To recall information, the brain transfers it back from connections to activity.

- This theory explains why long-term memories can be retained without neural activity.

- It’s also analogous to the RAM and hard drive in a computer. There’s a speed and stability tradeoff.

- This is also known as the “stability-plasticity” dilemma.

- Every neuron has two memory stores, one in its spiking pattern and one in its synaptic weight pattern.

- However, maybe lifetime memories depend more on the existence of the synapse rather than the synaptic strength.

- E.g. Your name and your age.

- While experience shapes connectome, genes also do.

Part III: Nature and Nurture

Chapter 6: The Forestry of the Genes

- The brain develops in four steps

- Neurons are created.

- They migrate to their proper place.

- They extend their branches.

- They make connections.

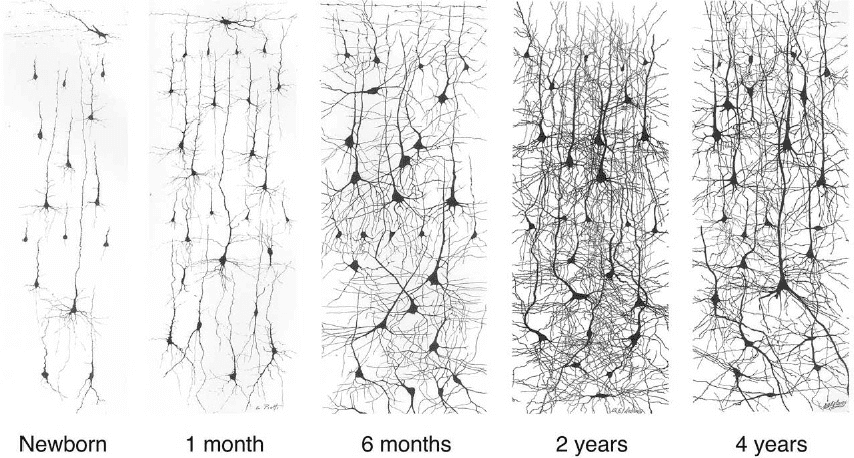

- By the time a baby is born, almost all of its neurons are there.

- Neurites grow quickly in childhood but eventually 40 percent of branches are pruned by adulthood.

- Why does the brain create so many synapses just to destroy them?

- Perhaps the early connectome is like a rough draft.

- In the beginning, the wiring is determined by our genes and randomness.

- But as time goes on, experience is likely the main driver of synapse elimination which leads to the elimination of the branch.

- It’s misleading to think of creation and destruction as happening in two phases.

- It’s just that the beginning has a net creation rate while the later stages have a net destruction rate.

- Brain development, writing an article, and economic growth are all involved in the interplay between creation and destruction.

- Maybe autism and schizophrenia arise from problems with a person’s connectome.

Chapter 7: Renewing Our Potential

- Most pairs of regions in the brain lack a connection between them.

- So any given region has a limited set of source and target regions called a connectional fingerprint.

- It’s suggested that a region’s function depends greatly on its wiring with other regions.

- E.g. The visual cortex is wired to the eyes.

- So changing the wiring of a brain area changes its function.

- A cortical area has the potential to learn any function but only if the necessary wiring with other brain regions exists.

- This puts a limitation on neural plasticity.

- The function of a cortical area is defined by its connections.

- Rewiring both creates and eliminates synapses, which goes against the idea that learning is simply synapse creation.

- There seems to be a critical period during human development for acquiring languages skills and vision skills.

- Once that period has passed, it’s very difficult or impossible to learn that skill.

- While there’s evidence that deprivation during the critical period leads to inability to pick up that skill, what about too much experience or enrichment?

- Cell death acts like a sculptor, chiseling away material rather than adding it.

- E.g. How fingers develop is that the cells between the fingers die, separating the fingers. If this didn’t occur, then we would end up with webbed hands and feet.

Part IV: Connectomics

Chapter 8: Seeing Is Believing

- To gain an unfair advantage in science, create tools that don’t exist.

- E.g. Galileo with his telescopes.

- Without the proper technology and tools, data doesn’t exist and progress halts.

- The improvements in cutting, collecting, and imaging aren’t enough to find connectomes.

- The scanning process creates too much data to handle, data on the order of petabytes.

- To find connectomes, we need not only machines for making images, but also machines for seeing them.

Chapter 9: Following the Trail

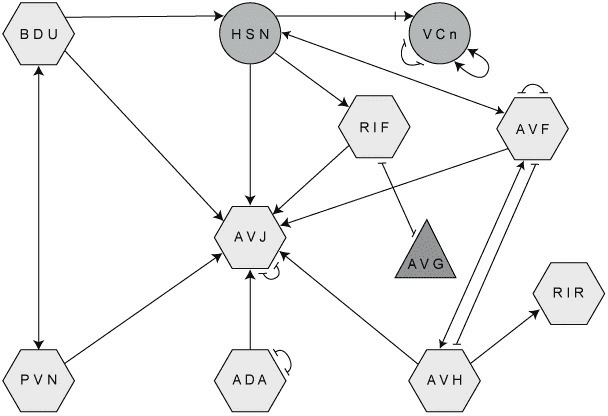

- Details the story the behind finding the C. Elegans connectome.

- The future of connectomics hinges on automating image analysis, not creating the images.

- The biggest problem right now isn’t creating the images of neurons, but the processing of those images.

- Processing the images requires segmenting the image into neurons and properly tracing them across all images.

- Sometimes, the people who are the best at doing something are the worst teachers because what comes to them as intuition isn’t taught to the student.

- Intelligence amplification (IA): the improvement of intelligence.

- The ultimate end goal is IA, not AI.

- What do we do after we get a connectome?

Chapter 10: Carving

- The cerebral cortex resembles a layered cake with layers of neurons, six of them to be precise.

- We can classify neurons based on their anatomy but also their connections.

- Neuron type connectome: a diagram showing how different neuron types are connected.

- These maps would be a refinement of Cajal’s neuron classification because connections depend on contact which is governed by location and shape.

- Brodmann relied on cortical layering to create brain maps and Cajal relied on neural shape and location.

- Associate every brain region with an elementary function, then explain more complex mental functions as combinations of elementary functions.

- This cooperation between elementary functions depends on the regional connections.

- Damage to a region impairs the corresponding elementary function. Damage to the connection impairs complex functions requiring cooperation.

- Beyond localization to connection.

- The $30 million Human Connectome Project is actually about regional connectomes, not neuronal connectomes.

- The difference is that one is about connections between brain regions while the other is about connections between neurons.

- The Broca-Wernicke model of language isn’t as clear cut as textbooks make it to be.

- Making a map of the brain is hard because the borders keep shifting, growing, and shrinking.

- The author believes we should start with the structure instead of function because the function is dependent on the structure.

- Localizationism attempts to establish a one-to-one correspondence between mental functions and cortical areas yet this isn’t true.

- Most mental functions require the cooperation of multiple areas and most areas are used in multiple functions.

- The correct approach is to start from the bottom up with the structure and then to deduce the function.

- This parallels what happened with genes and Mendelian genes.

- We thought that genes mapped one-to-one to physical traits yet that isn’t true. Some genes code for multiple traits and some traits require multiple genes.

- We expect to see the same regions and neuron types across all human brains because they’re highly controlled by our genes.

- However, at the neuron level we expect to see differences due to different experiences.

Chapter 11: Codebreaking

- We’ll have to learn how to decode connectomes to understand them.

- Patient H.M. had his medial temporal lobe (MTL) removed to prevent seizures.

- MTL seems essential for storing new memories but not for retaining old ones.

- H.M. could form new nondeclarative memories which suggests declarative memories to be separate.

- Connectomes must contain synaptic weight information to be decoded.

- Reweighing vs reconnection.

- Connectomics reveals the latter but not the former.

Chapter 12: Comparing

- Twins are unsettling because they challenge our assumption that every human being is unique.

- The partial connectome between two C. Elegans aren’t the same which demonstrates early evidence that connectomes aren’t the same.

- Neurons with many synapses are likely the same but neurons with few synapses are likely different.

- Why do axons bundle in white matter?

- They’re shortcuts.

- The path has been established by other axons.

- Hypothesis approach to science

- Formulate a hypothesis, our best guess of a phenomenon.

- Make a prediction based on the hypothesis.

- Perform an experiment to test the prediction.

- Data approach to science

- Collect a vast amount of data.

- Analyze the data to detect patterns.

- Use these patterns to formulate hypotheses.

- This parallels Thomas Kuhn’s idea that science progresses on two fronts, novelty in theory and novelty in evidence.

- To understand why minds differ, we have to see how brains differ. That’s why connectomes are important.

Chapter 13: Changing

- The best way to change a brain is to help it change itself.

- Two approaches to preventing neurological disorders

- Prevention

- Intervention

- The rest of the chapter is on drugs using either approach and how the connectome may help.

Part V: Beyond Humanity

Chapter 14: To Freeze or to Pickle?

- Over the course of history, death has been repeatedly redefined based on current medical knowledge.

- It used to be that death was when breathing didn’t occur and when the heart stopped beating.

- In the present, it’s when the brain and brainstem are destroyed or inactive.

- In the future, death will be defined by the destruction of the connectome.

Chapter 15: Save As…

- Religion has a vague description of heaven because people would rather fantasize about their own heaven than have one thrust upon them.

- Simulation, such as brain simulation, starts from the wish to reproduce an interesting phenomenon and tries to find the data necessary to do it.

- This leads to wishful thinking.

- There needs to be a well-defined criterion for judging success in brain simulation.

- The Turing test will tell us when we’ve reached our destination but we need a way of knowing if we’re going in the right direction.

- Brain simulation is nearly the same as artificial intelligence.

- If all parts of a machine are the same, then the functionality of the machine depends entirely on the organization of its parts.

- The progression of identity

- You are a bunch of atoms.

- You are a machine of DNA.

- You are a bunch of information.

Epilogue

- Connectionism emphasizes the importance of connections for mental function.

- The flow of neural activity through our connectomes drives our experiences of the present and leaves behind impressions that become our memories of the past.

The young boy laughed as he splashed in the water. Returning to land, he asked, “Teacher, why does the stream flow?” The old man gazed silently at the novice and replied, “Earth tells water how to move.” During their journey back to the temple, they crossed a precarious footbridge. The novice clutched the old man’s hand tightly. He looked at the stream far below and asked, “Teacher, why is the canyon so deep?” As they reached the safety of the other side, the old man replied, “Water tells earth how to move.”